Authored By: Michelle Levy

Edited By: Kandice Sharren and Sara Penn

Submitted on: 04/26/2019

Citation: Levy, Michelle. "Mother Shipton: The Oldest Woman in the WPHP." The Women's Print History Project, 26 April 2019, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/4.

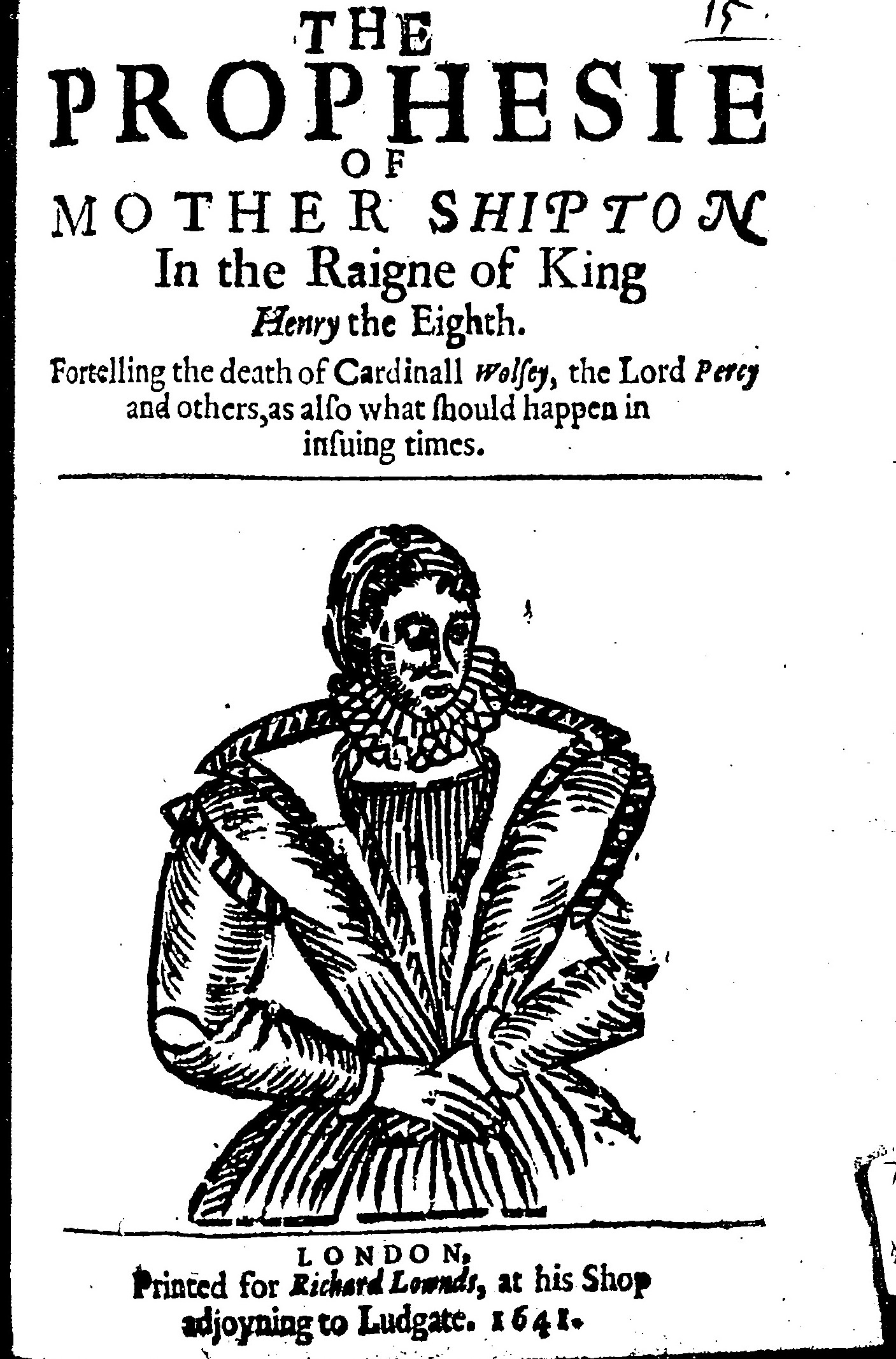

Figure 1. Rauner Special Collections Library, Dartmouth College.

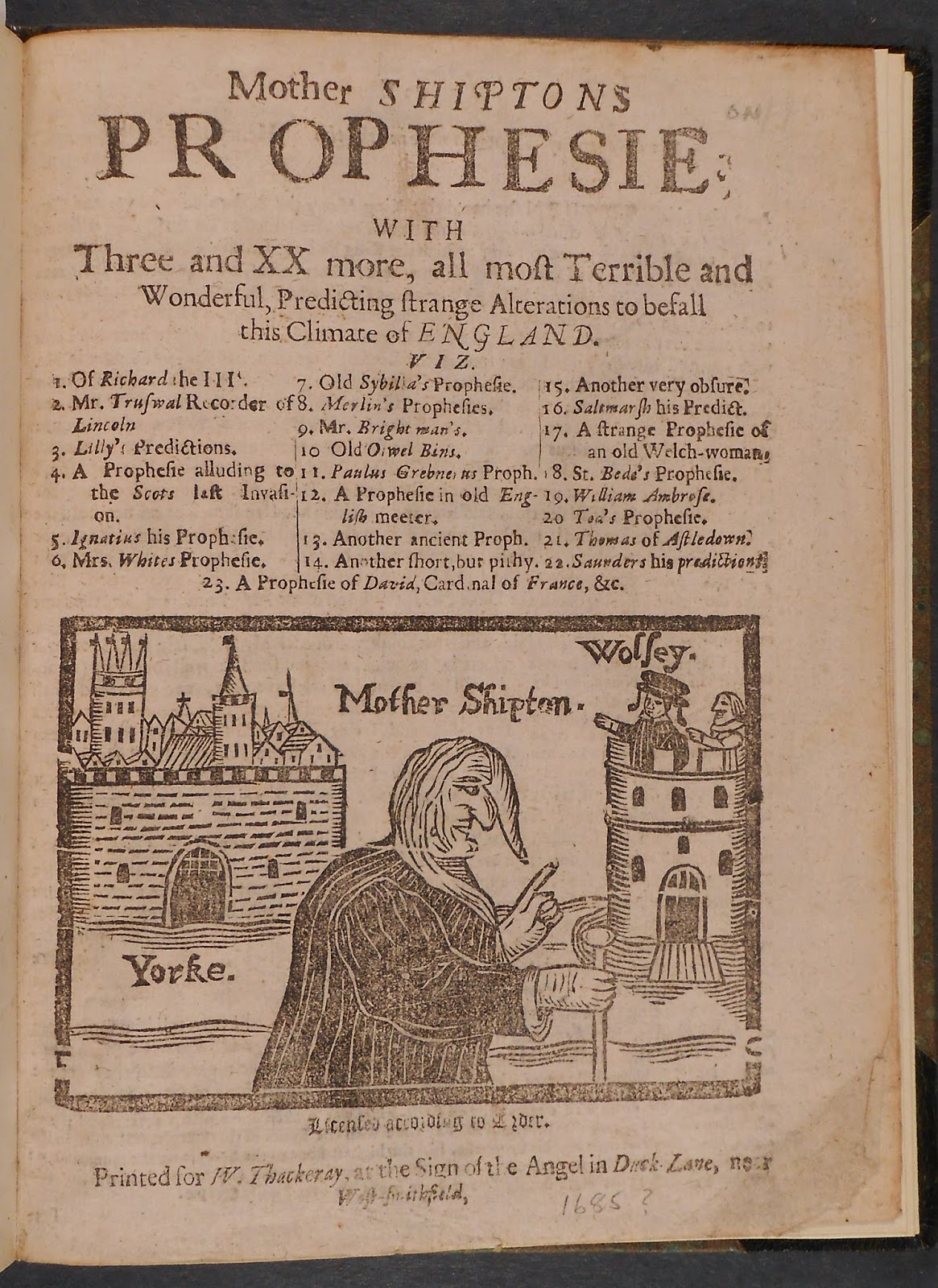

The oldest woman whose titles appear in WPHP is Ursula Southeil, who appears to have lived in York, England in the Tudor period. I say "appears," since, according to Arnold Kellet, “The only historical support for her existence as a woman living in Tudor York is found in the slim pamphlet The Prophesie of Mother Shipton in the Raigne of King Henry the Eighth (1641), which opens with an account of the prediction which apparently brought her national fame.” This prediction was in relation to Cardinal Thomas Wolsey (1473–1530). Wolsey, who had planned his first visit to York in 1530, had been in trouble with Henry VIII due to his failure to negotiate an annulment of his (Henry's) marriage to Katherine of Aragon with Rome. According to the pamphlet, Mother Shipton prophesied that even though Wolsey would see York at a distance, he would never enter the city. The pamphlet also explains that Wolsey sent three of his men to interrogate Shipton, and vowed that she would be burnt at the stake as a witch when he arrived. In fact, Wolsey was arrested on 4 November 1530 just outside of York, in Cawood, on a charge of high treason and died en route to London. Southeil's prophesy was correct; he never entered York. A title page woodcut depicting the prophesy is found in this 1681 printing of Mother Shiptons Prophesie. Here we see how Mother Shipton is figured as a hag, but also as one who wields actual power, as she chastizes Wolsey by pointing her finger at him.

The slim pamphlet ends with a reference to a ship sailing up the Thames and finding the city of London in ruin. This was taken to be a prediction of the fire of London, as we know from a reference in the diary of Samuel Pepys (20 October 1666), who stated that when Prince Rupert on board ship heard of the fire he simply said "now Shipton's prophecy is out" (Pepys 7.333) (Kellet).

Virtually nothing is known about Shipton besides what is related in this volume, which, it must be recalled, appeared more than a century after the events it relates. Historians have debated whether Mother Shipton was in fact an actual person, or just a myth.

Figure 2. The Great Fire of London in the Year 1666, by William Birch, 1792. Wikimedia Commons.

Mother Shipton’s continued presence in popular culture shifted over time. According to Lauren McCrane, by the eighteenth century, she became more of “a literary device rather than [an] historical figure”; she “pervaded popular works of the period even as her significance became more diffuse and indeterminate” (371). She continued to be associated with witchcraft; thus in 1759, Carl Alexander Clerck named a moth after her, due to the hag-like markings on the wing. But she also continued to be viewed as a female truth-teller, as befits the account of her Wolsey prediction, in which she is figured as a woman speaking truth to power. She features throughout the eighteenth century as a complicated feature especially in different performance genres, in puppetry, pantomime, masquerade, and ballad. She was also featured at Mrs. Salmon’s Royal Wax-Works, at 189 Fleet Street; of over two hundred figures displayed at the museum, one of the most intriguing to eighteenth-century visitors was an automaton of Mother Shipton, who kicked visitors as they left the museum (McCrane 370).

Figure 3. Image of a Mother Shipton Moth. Wikimedia Commons.

The titles we have by Mother Shipton in WPHP are works of popular children’s literature. In Mother Shipton's legacy. Or, a favourite fortune-book in which is given, a pleasing interpretation of dreams: and a collection of prophetic verses, moral and entertaining, published in York in 1797, Mother Shipton has been transfigured into a school marm, who prophesies that “Tommy Noodle” will be whipped that day, a prediction that turns out to be correct (the boy is whipped by his father for stealing apples). The work also includes moralistic, nursery-rhyme duties, such as:

He who wishes to grow wise,

At six o’clock must always rise;

And if you loiter, Master Ned.

You supperless must go to bed. (6).

Of course, these words were neither written nor imagined by the historical Mother Shipton, if she existed. It may be questionable, therefore, whether Mother Shipton, and her titles, should appear in the WPHP. As a recurring, influential and complex female figure who pervades popular literature and culture of the period, however, we believe she has earned her place.

WPHP Records Referenced

Southeil, Ursula (person, author)

Mother Shipton's Legacy (title)

Works Cited

Kellett, Arnold. "Shipton, Mother, supposed witch and prophetess." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/25420

McGrane, Laura. “Bewitching Politics and Unruly Performances: Mother Shipton Gets Her Kicks in Restoration and Eighteenth-Century Popular and Print Culture.” Forum for Modern Language Studies, vol. 43, no. 4, 2007, pp. 370–84.

Shipton, Ursula. Mother Shipton's legacy. Or, a favourite fortune-book in which is given, a pleasing interpretation of dreams: and a collection of prophetic verses, moral and entertaining. Printed for Wilson, Spence, & Mawman, Anno, 1797.