This post is part of our Women & History Spotlight Series, which will run through March 2021. Spotlights in this series focus on women's contributions to history in the database.

Authored by: Amanda Law

Edited by: Michelle Levy and Kandice Sharren

Submitted on: 03/19/2021

Citation: Law, Amanda. "Taking Up the Cause: Mary Hays's Female Biography." The Women's Print History Project, 19 March 2021, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/68.

Figure 1. Title page of Mary Hays’s Female Biography, 1803. Google Books.

“My pen,” Mary Hays (1759–1843) writes in her preface to Female Biography; or, Memoirs of Illustrious and Celebrated Women, of All Ages and Countries. Alphabetically Arranged, “has been taken up in the cause, and for the benefit, of my own sex” (iii). She continues to describe how this six-volume project, containing descriptions of over three hundred women spanning over two millennia, is intended not only to uncover a history of women who are traditionally blotted out by a discourse and canon dominated by men, but to instruct and entertain women themselves. She writes,

Women, unsophisticated by the pedantry of the schools, read not for dry information, to load their memories with uninteresting facts, or to make a display of vain erudition. A skeleton biography would afford to them but little gratification: they require pleasure to be mingled with instruction, lively images, the graces of sentiment and the polish of language. (iv)

While this assertion could be read as Hays underestimating women’s intellectual ability measured against their educated male counterparts, she also recognizes that women are not afforded the same access to education as men, resulting in different readerly and intellectual sensibilities. Gina Luria Walker explains that “In contrast to Mary Wollstonecraft, whose political intention was to interrupt the conversation among ‘canonized forefathers’ . . . Hays struggled to know what her erudite male associates knew and to translate what she learned into accessible forms for her female contemporaries” (“Introduction” 6). Female Biography serves to disrupt history predominantly written by and about men, but for Hays, it more importantly spoke to and enriched the lives of women themselves.

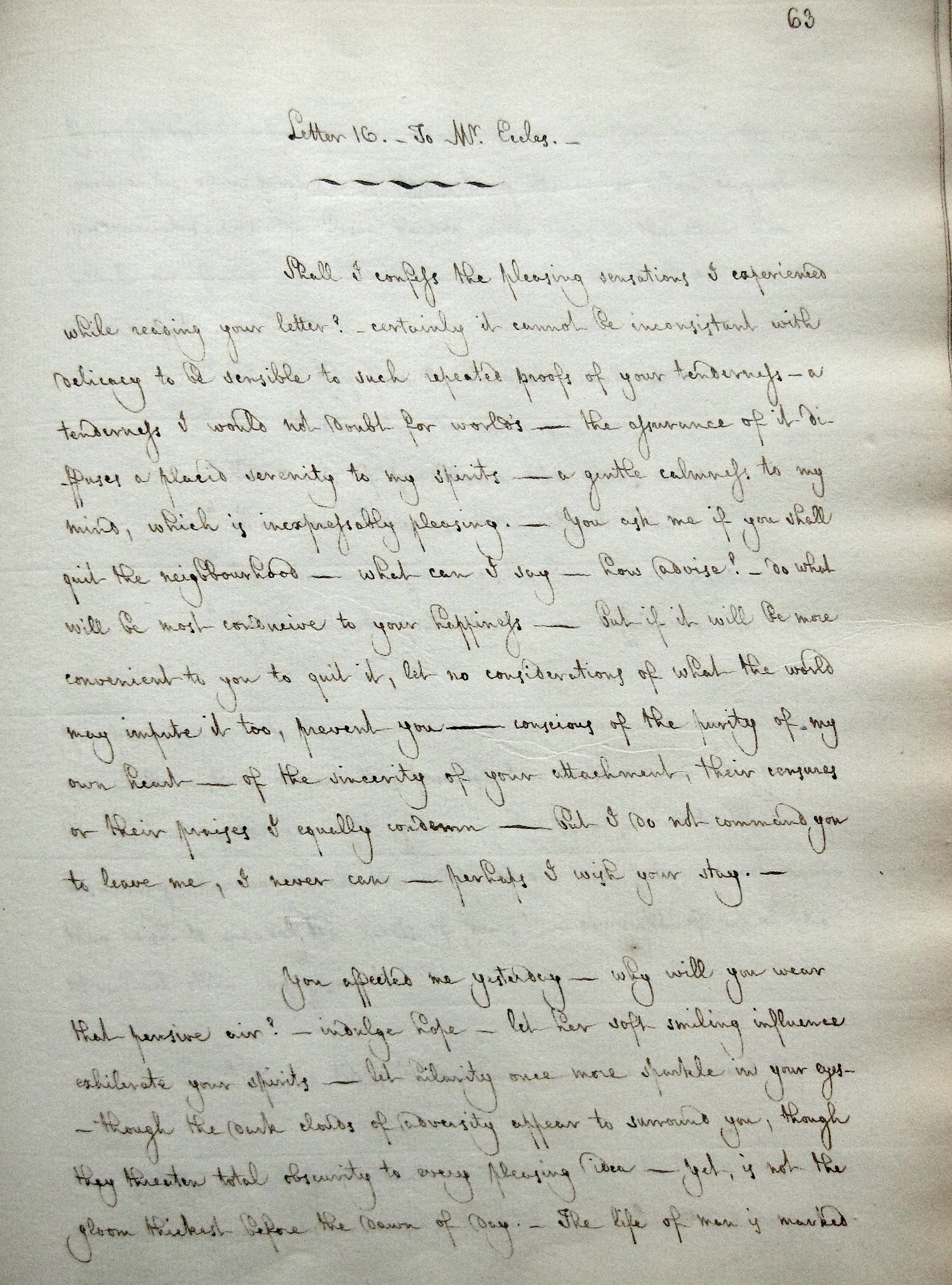

Mary Hays was born into a middle class Dissenting family which began to struggle after the early death of Hays’s father who supported the family as a ship captain. From a young age, Hays was aware of the issues that would later inform her writing, such as women’s unequal access to education, the restrictive moral and societal expectations placed on women, and her own thirst for knowledge. In love letters sent to John Eccles between 1779 and 1780, she expressed, according to Walker, her “resistance to existing constraints on female education; skepticism about conventional expectations for female behaviour, especially the insistence on chastity; longing for independence, and both solitude and intimacy; identification with strong, learned women of the past; [and] desire to know what men knew” (The Idea of Being Free 13). Though her conventional education was limited due to her gender and class, her religious upbringing and close contact with Dissenting figures fueled her search for knowledge and facilitated her self-education. In 1780, Hays met the iconoclastic Baptist preacher Reverend Robert Robinson who provided Hays with books about advanced Enlightenment principles. Walker suggests that Robinson was the most important educational figure in Hays’s life as he instigated Hays’s “understanding of the search for truth as the means of individual and societal freedom” (The Idea of Being Free 14).

Figure 2. Letter from Mary Hays to John Eccles, 9 August 1779, from fol. 63 of Volume 1 of the Hays-Eccles Correspondence, Mary Hays Material, Carl H. Pforzheimer Collection of Shelley and His Circle, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations, Mary Hays: Life, Writings, and Correspondence.

After Robinson’s death, Hays went on to reach out to other Dissenting leaders in order to further her education and applied the principle of rational inquiry as the key to freedom in all her works. Hays’s first publication was a pamphlet titled Cursory Remarks on an Enquiry into the Expediency and Propriety of Public or Social Worship (1791, 1792) which she authored under the pseudonym Eusebia (who was the second wife of Roman emperor Constantius II and who can be found in volume four of Female Biography). This pamphlet was written in response to Gilbert Wakefield, a classicist scholar at New College, who published a critique of Dissenting religious practices. Hays’s response was accompanied by those of several Dissenting leaders, including Anna Laetitia Barbauld’s Remarks on Mr. Gilbert Wakefield's Enquiry into the Expediency and Propriety of Public or Social Worship (1792), and garnered praise from several of these influential figures. Hays’s pamphlet and the attention it drew secured her a place in “the dissident republic of letters” (Walker, The Idea of Being Free 17), which was increasingly under attack as Britain geared up for war against revolutionary France in 1793. Walker states that “[a]fter Mary Wollstonecraft published A Vindication of the Rights of Woman in 1792, the state of siege soon included those ‘gallic philosophesses’—Hays, Anna Barbauld, Charlotte Smith, and Helen Maria Williams—as equal objects of public and governmental hostility with the Jacobin men” (The Idea of Being Free 17). Amid this tumultuous landscape, Hays released her first book in 1793, Letters and Essays, Moral and Miscellaneous, which gained her additional scorn from conservative critics.

Hays became close friends with Wollstonecraft as they shared ideals and experiences as public women intellectuals. Hays’s Memoirs of Emma Courtney was published in 1796 and gained Hays the most controversy of all her published works. Based on Hays’s own correspondence with Unitarian William Frend and Wollstonecraft’s husband, William Godwin, readers were outraged by Hays detailing her romantic and sexual passions towards Frend and criticizing “the hypocrisy of masculine promises of the Enlightenment freedoms” (Walker, The Idea of Being Free 18) in her correspondence with Godwin. After Wollstonecraft’s death in 1797, Hays anonymously published her Appeal to the Men of Great Britain in Behalf of Women (1798, 1798), although she published The Victim of Prejudice in 1799 with the attribution “By Mary Hays, author of The Memoirs of Emma Courtney.” Along with backlash from the publication of Emma Courtney, Hays was also facing reactions against radical women writers in the aftermath of Wollstonecraft’s death. Andrew McInnes notes that William Godwin’s “notoriously candid” memoir of Wollstonecraft’s life “left a complicated and fiercely contested legacy for women writers in the early nineteenth century” (273). Reactionary conservative critics used the information in Godwin’s memoir to paint Wollstonecraft as promiscuous and dangerously subversive and women who followed in her legacy, like Hays, felt the repercussions of this association. Considering Hays and Wollstonecraft’s friendship and the backlash after Wollstonecraft’s death, several scholars have noted her conspicuous absence from Female Biography. Some critics label the omission as “intellectual cowardice” (Taylor qtd in. McInnes 274) and argue that the Biography focuses on “domestic heroism” (Spongberg qtd. in McInnes 274) in order to dilute Wollstonecraftian concerns, but others, such as McInnes, suggest that Hays wove Wollstonecraft’s ideals into the Biography more subtly in order to adapt to a more reactionary historical moment.

Figure 3. Title page of Hays’s Memoirs of Emma Courtney, 1796. ECCO.

Hays published Female Biography in 1803, during “the encyclopedism boom” (Walker, “Introduction” 11) and her publisher, Richard Phillips, who was also a Dissenter, had already authored and published multiple encyclopedias. Walker explains that Dissenters such as Hays and Phillips had a special interest in the genre of encyclopedia because the compilation of factual information was seen as a method of cleansing “knowledge-ordering systems of superstition and prejudice” (“Introduction” 11). Mary Spongberg et al. describe Hays’s Biography as “the first Enlightenment prosopography of women and a compelling response to the great forgetting of women in traditional histories” (706).

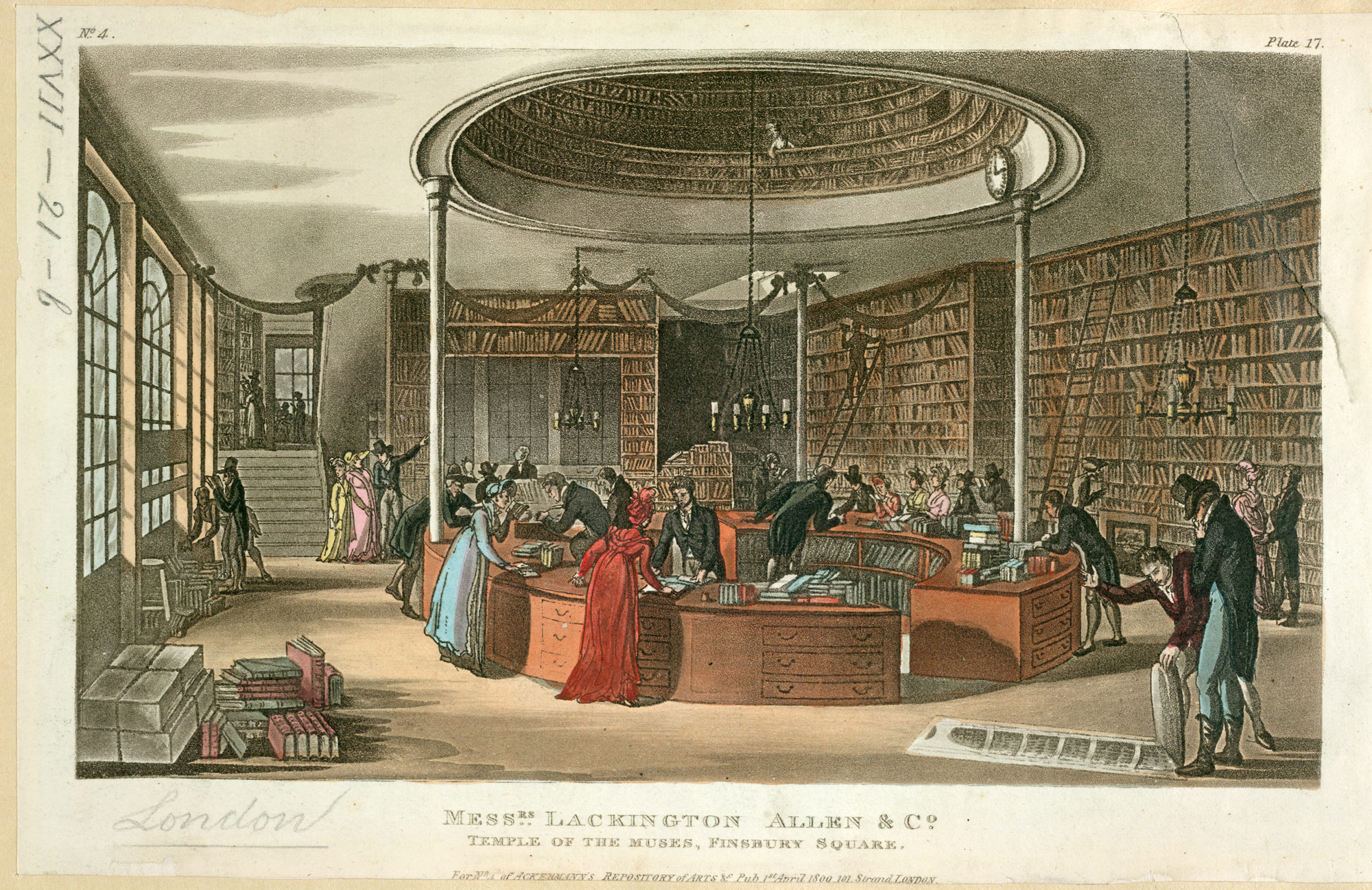

According to Walker, there are few documents that record Hays’s activity while writing and how she obtained her sources for the Biography, but she and the scholars of The Female Biography Project have documented one hundred of Hays’s sources. These include Jean Francois De Lacroix’s 1769 Dictionnaire historique portatif des femmes célebres, Pierre Bayle’s 1697 Dictionnaire historique et critique, Plutrach’s Morals and Lives, and Jemima Kindersley’s 1781 translation of An Essay on the Character, The Manners, and The Understanding of Women, in Different Ages (Whipp 57-58). Hays’s letters suggest that she had access to William Tooke and his father’s extensive private library and also obtained materials from publishers Joseph Johnson and James Lackington (Walker, “Introduction'' 12). She also contacted writers Robert Southey and Anna Laetitia Barbauld for historical works in their possessions, but Walker indicates that this is where the trail of her sources trickles off (See Timothy Whelan’s Mary Hays: Life, Writing, and Correspondence for an extensive catalogue of Hays’s correspondences through which Whelan has mapped Hays’s sources). In the preface to the Biography, Hays herself gestures to the incompleteness of sources for a project of this scope, writing that

[t]o give an account, however concise or general, of every woman who, either by her virtues, her talents, or the peculiarities of her fortune, has rendered herself illustrious or distinguished, would, notwithstanding the disadvantages civil and moral under which the sex has laboured, embrace an extent, and require sources of information, which few individuals, however patient in labour or indefatiguable in research, could compass or command. (iii)

Hays’s work was not only limited by the impossibility of a single person reading and compiling all available sources, but by the absence of material as well. Walker notes that there were innumerable women of note, such as Lucy Hutchinson and Phillis Wheatley, “of whom Hays was oblivious because they had been dismissed from male memory and knowledge-ordering systems and only recovered more recently” (“Introduction” 13). In addition, as Hays was self-educated and knew only French in addition to English, she lacked the ability to read the works of several of her subjects in their own languages.

Figure 4. Messrs. Lackington Allen & Co: Temple of the Muses, Finsbury Square, Rudolph Ackerman, 1809. British Library.

Female Biography gained critical and popular attention, evidenced by the fact that it was “reprinted in numerous editions in England and America in the nineteenth century” (Walker, The Idea of Being Free 264) and “was the standard reference work on women for at least 50 years” (Walker, The Idea of Being Free 283). The first American edition was published in 1807 and the WPHP is currently working on adding other editions. Hays earned enough royalties from the publication of the Biography to buy a house outside of London and she wrote to her friends and associates that she was living in retirement, but continued to write voraciously. She continued her ventures in history writing by completing the third volume of The History of England, from the Earliest Records to the Peace of Amiens; in a Series of Letters to a Young Lady at School (1806), which Charlotte Smith began, but grew too ill to finish (Look forward to next week’s Spotlight by Caelen Campbell on Charlotte Smith’s history writing!). She came into conflict with Phillips, who was also the publisher of The History of England, because he refused to pay her for completing The History which resulted in Hays pursuing a lawsuit against him. As indicated by the intended youthful readership of The History of England, Hays began to turn in the direction of children’s literature in her later writing. She wrote Harry Clinton: A Tale for Youth (1804) and Historical Dialogues for Young Persons (1806-1808), which Eleanor Ty describes as “more didactic and conservative” than her earlier writing, likely due to the backlash against radical women writers after Wollstonecraft’s death. Her last two novels, The Brothers; or, Consequences. A Story of What Happens Every Day. Addressed to that Most Useful Part of the Community, the Labouring Poor (1815) and Family Annals; or, The Sisters (1817), were equally didactic but were intended more for a lower class audience to teach them values of economy and frugality.

For her final publication in 1821, Hays referenced her research from Female Biography in Memoirs of Queens, Illustrious and Celebrated. Inspired by the divorce trial of Queen Caroline and King George IV in 1820, Hays compiled the lives of seventy queens, half of whom she had already included in Female Biography. Despite enduring a brutal backlash from conservative critics and witnessing her own decline in popularity due to a combination of this negative publicity and the rise of younger, more popular writers, Hays continued to staunchly advocate for women's equality. In the preface to Memoirs of Queens, Hays writes,

I maintain, and, while strength and reason remain to me, ever will maintain, that there is, there can be but one moral standard of excellence for mankind, whether male or female, and that the licentious distinctions made by the domineering party, in the spirit of tyranny, selfishness, and sensuality, are at the foundation of the heaviest evils that have afflicted, degraded, and corrupted society: and I found my arguments upon nature, equity, philosophy, and the Christian religion. (vi)

WPHP Records Referenced

Hays, Mary (person, author)

Female Biography; or, Memoirs of Illustrious and Celebrated Women, of All Ages and Countries. Alphabetically Arranged (title, first London edition)

Wollstonecraft, Mary (person, author)

Cursory remarks on An enquiry into the expediency and propriety of public or social worship: inscribed to Gilbert Wakefield (title, 1791 first edition)

Cursory remarks on An enquiry into the expediency and propriety of public or social worship: inscribed to Gilbert Wakefield (title, 1792 second edition)

Barbauld, Anna Laetitia (person, author)

Remarks on Mr. Gilbert Wakefield's Enquiry into the Expediency and Propriety of Public or Social Worship (title, 1792 first edition)

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with strictures on political and moral subjects. (title)

Smith, Charlotte Turner (person, author)

Williams, Helen Maria (person, author)

Letters and Essays, Moral and Miscellaneous (title)

Memoirs of Emma Courtney (title)

Godwin, William (person, author)

Appeal to the Men of Great Britain in Behalf of Women (title, 1798 first edition)

Appeal to the Men of Great Britain in Behalf of Women (title, 1798 reprint)

The Victim of Prejudice (title)

Phillips, Richard (firm, publisher)

Kindersley, Jemima (person, translator)

An Essay on the Character, The Manners, and The Understanding of Women, in Different Ages (title)

Johnson, Joseph (firm, publisher)

Lackington, James (Lackington, Allen, and Co.) (firm, publisher)

Southey, Robert (person, author)

Hutchinson, Lucy (person, author)

Wheatley, Phillis (person, author)

Female Biography; or, Memoirs of Illustrious and Celebrated Women, of All Ages and Countries. Alphabetically Arranged (title, first American edition)

Harry Clinton: A Tale for Youth (title)

Historical Dialogues for Young Persons (title)

Family Annals; or, The Sisters (title)

Memoirs of Queens, Illustrious and Celebrated (title)

Works Cited

Hays, Mary. Female Biography; or, Memoirs of Illustrious and Celebrated Women, of All Ages and Countries. Alphabetically Arranged. By Mary Hays. In six volumes.Richard Phillips, 1803.

Hays, Mary. Memoirs of Queens, Illustrious and Celebrated. By Mary Hays, Author of the Female Biography, Historical Dialogues, Harry Clinton, The Brothers, Family Annals, &c. &c. Thomas and Joseph Allman, 1821.

McInnes, Andrew. “Feminism in the Footnotes: Wollstonecraft’s Ghost in Mary Hays’ Female Biography.” Life Writing, vol. 8, no. 3, Sept. 2011, pp. 273–85.

Spongberg, Mary, et al. “Female Biography and the Digital Turn.” Women’s History Review, vol. 26, no. 5, Sept. 2017, pp. 705–20.

Ty, Eleanor. “Critical Biography.” The Mary Hays Website, 2000, http://web.wlu.ca/english/ety/biography.html.

Walker, Gina Luria. “Introduction.” The Invention of Female Biography, Routledge, 2017, pp. 3–18.

Walker, Gina Luria, editor. The Idea of Being Free: A Mary Hays Reader. Broadview, 2005, https://www.deslibris.ca/ID/419069.

Whipp, Koren. “Finding Anonymous.” The Invention of Female Biography, edited by Gina Luria Walker, Routledge, 2017, pp. 55–69.

Further Reading

Peterson Pittock, Sarah. “Mary Hays’s Female Biography: Feminist Remix.” Women’s Writing, vol. 25, no. 2, Apr. 2018, pp. 219–34.

Walker, Gina Luria. “‘I Sought & Made to Myself an Extraordinary Destiny.’” Women’s Writing, vol. 25, no. 2, Apr. 2018, pp. 124–49,

Whelan, Timothy. Mary Hays: Life, Writing, and Correspondence. http://www.maryhayslifewritingscorrespondence.com/.