Authored by: Isabelle Burrows

Edited by: Michelle Levy and Kandice Sharren

Submitted on: 06/21/2021

Citation: Burrows, Isabelle. “‘Beauty in Search of Knowledge:’ Fashion and Print in the Eighteenth Century.” The Women’s Print History Project, 21 June 2021, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/73

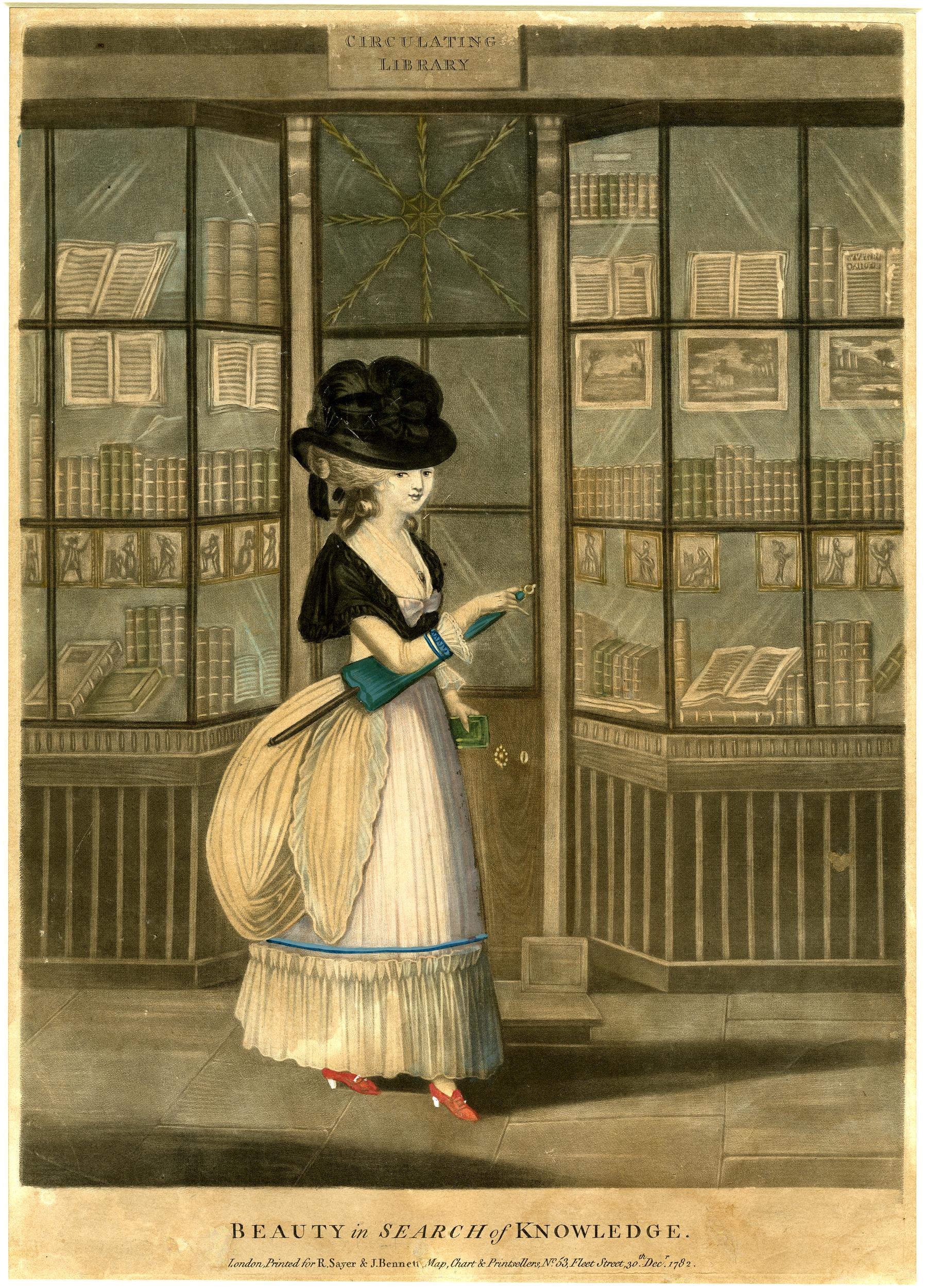

Figure 1. “Beauty in Search of Knowledge,” printed by Sayer and Bennett, 1782. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

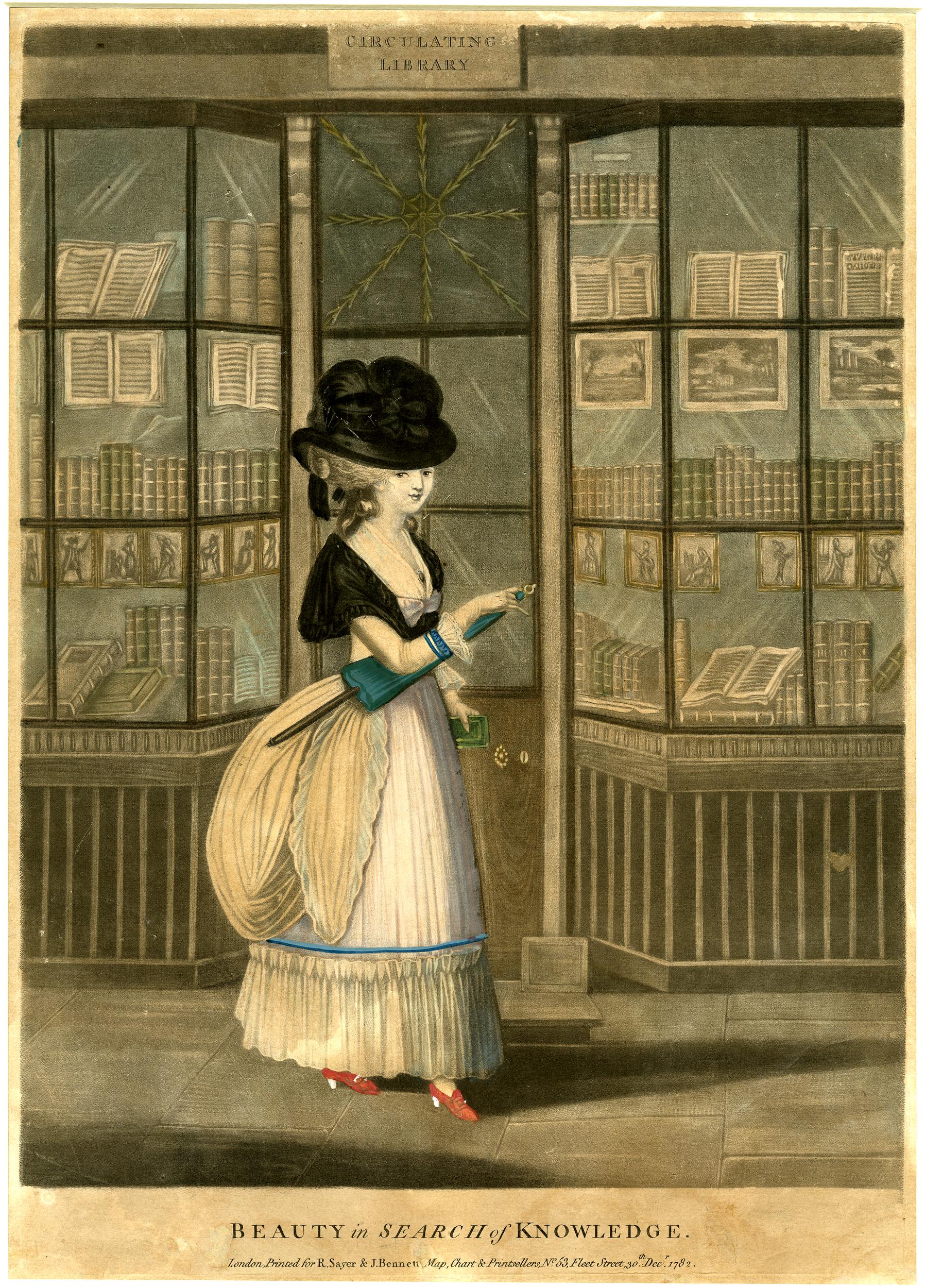

Figure 2. John Raphael Smith’s 1781 drawing of a fashionable lady outside a circulating library. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The print that has graced the landing page of The Women’s Print History Project since its launch in 2019 is the hand-coloured mezzotint titled “Beauty in Search of Knowledge,” published on 30 December 1782 by R. Sayer and J. Bennet, Map, Chart & Printsellers, No. 53 Fleet Street. This image, which shows a fashionable woman holding a book and parasol in front of a shop display, is based upon a 1781 chalk drawing by John Raphael Smith. According to fashion historian Peter McNeil in the only scholarly examination of the mezzotint, “the principle joke of this gentle caricature of contemporary life is that the lady is about to indulge in reading a lightweight, fashionable novel from which she will gain very little real knowledge” (223). However, McNeil acknowledges that “there are deeper levels of meaning at work,” and placing the mezzotint, the drawing, and the fashionable figures who inspired both, in close conversation reveals a complicated relationship between fashion, print, and commercial culture. This post, which focuses on the relationship between Beauty’s clothing, the origins of fashion, and print, is the first of a series which will examine the “deeper levels of meaning” at which McNeil hints. The series will highlight the nuances of culture, society, and economy that the print contains as we take the opportunity to reflect on the relation between Beauty’s world of print, and the world of print that we address in the WPHP.

Beauty's Hat

Figure 3.

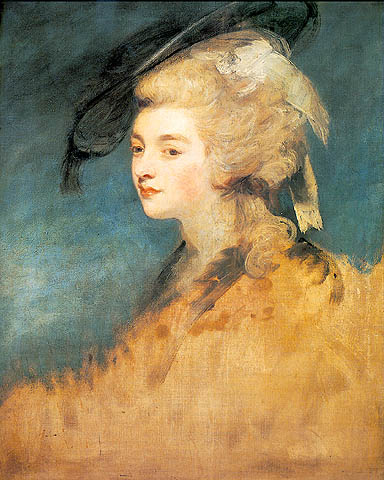

Beauty’s stylish hat demonstrates the change in silhouette from the tall, slim 1770s to the wide and airy profile that would continue to grow throughout the 1780s and into the 1790s. Beauty is pictured in a very acceptable rendition of the Devonshire hat, named for its most famous wearer, the tastemaker, aristocrat, and fashion icon Georgiana, duchess of Devonshire. Although Gainsborough’s famous portrait of the Duchess is dated to 1787, a few years after the creation of our print, the Devonshire hat was already a signature of Georgiana’s brand from as early as 1781, and remained in vogue for much of the decade. The June edition of the Lady’s Magazine describes fashionable “half-dress” for June 1781 as including the “Devonshire hat,” (287), and while trimmings and materials for these massive hats changed with the seasons, they remained a necessary article from at least 1781 to 1783 (LM, 1781 287; 1783 187).

Figure 4. Gainsborough’s portrait of the fashionable Mrs. Siddons in a modish Devonshire hat, 1785. © National Gallery London.

Hair and Complexion

Figure 5.

The hair of the eighteenth century lady evolved with the hats which adorned it, and the wide, low puff, with the draping curls was a perfect complement to the wide frame created by the hats of the moment. The Lady’s Magazine of March 1783 describes a must-have style very similar to Beauty’s: “Hair dressed broad, but not high, two curls low on the shoulders; white powder” (LM, 1783 121). Beauty’s face is as stylishly pale as her hair, probably through a combination of sun protection from the excessive hat and the redundant parasol, but likely due to powder as well. One disgruntled husband of the day expressed his disappointment with the artifice fostered by the powder trend: “I lament old times when powder was only worn by players” (LM, 1782 406).

Figure 6. Joshua Reynolds’ unfinished portrait of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, with fashionable powdered hair, 1780. Wikipedia.

Fichu/handkerchief

Figure 7.

Another accessory which aided in the preservation of the fashionable pallor was the handkerchief, or fichu, worn over the shoulders. Though its ostensible purpose was to protect from the sun and fill in the low bodice neckline, the neck handkerchief also created an opportunity for a display of conspicuous consumption. As this museum example shows, the fichu was usually made of very fine fabrics, often embellished with lace or embroidery, and all this delicacy and detail came with a price. Like any accessory, the fichu varied with seasonal fashions. In 1781 alone, the handkerchief fashions varied from “large double handkerchiefs'' in June (LM, 1781 287), to “The gordon handkerchief, buttoned round the neck” in December 1780 (30–31), to the “large Vandyke handkerchiefs” (LM, 1781 153), very expensive lace articles in the overstated style of the 1600s.

Figure 8. Elisabeth Vigee-Lebrun’s portrait of La Comtesse de la Chatre with white fichu, 1789. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Shawl

Figure 9.

Too small to provide much protection from the elements, the shawl serves almost no practical purpose in the ensemble, except to coordinate with the hat and set off the pale complexion and dress of the wearer. Trends for black accessories grew along with trends for black cloaks in 1783 (LM 121).

Figure 10. Fanny Burney painted in a black shawl by Edward Francisco Burney, c. 1784–1785. © National Portrait Gallery.

Polonaise Gown

Figure 11.

Beauty’s pale ivory-yellow gown exemplifies the craze for the Polonaise. The Polonaise over-gown first emerged in the 1770s as an evolution of the robe a la Francaise, a gown which had enjoyed popularity earlier in the century. As the dimensions of paniers and hoop-petticoats decreased from the court splendour of the 1760s to the rounder, softer silhouette of the 80s and 90s, the neck-to-ankle back drapery of the Francaise took on a new form in the bunches and gathers of the Polonaise (Waugh 73). Though the Francaise didn’t die out overnight, the tight, close bodice and bustle-like draping of the Polonaise (or Polonese, or Poloneze) was, by the time of our print’s creation in 1782, a ubiquitous presence in a fashionable woman’s wardrobe. The Lady’s Magazine for 1781 names iterations of the Polonaise as stylish items almost monthly, and Beauty’s dress in the print seems very similar to the fashionable “Half-dress” (think semi-formal evening) and “Deshabille” (think casual day wear) of January 1781: “Half dress: Long Polonese gowns over puckered satin [petti]coats, trimming quite round the gown… The Deshabille: short Polonese, with long sleeves” (LM 16). Beauty’s tight, white Polonaise is well within the bounds of “Deshabille” vogue: “a long dress made of fine muslin, and trimmed with lace, the body to fit close to the waist in the form of a polonaise; the sleeve long, and tight to the arm” (LM, 1783 121).

Figure 12. A white polonaise of c. 1780. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Petticoat

Figure 13.

You’d be forgiven for thinking the pale cream-pink skirt of our Beauty’s outfit was a part of the gown, but as suggested by the descriptions of the Polonaises above, the skirt, or petticoat, was in fact a separate (though equally important) item from the gown. Petticoats, gathered, ruffled, or “puckered,” (in the language of the day) were an ideal canvas for embellishment, as they were displayed by the fashionable cutaway skirts of the Polonaise gown. The decorations of a petticoat were important enough to be recorded and reported on, as occurred on one occasion in April 1782, when Marie-Antoinette’s “puckered petticoat of gauze or sarsnet” made international news as the “Fashionable dress at Paris” for the English readers of the Lady’s Magazine (LM, 1782 195).

Figure 14. Fashion plate with polonaise and ruffled, tiered petticoat, c. 1780s. V&A.

Shoes

Figure 15.

People looking back at history joke about the scandal of an exposed ankle, but in the 1770s to 80s, such a joke would’ve fallen flat. The bulk of the fashionable Polonaise suited a shorter skirt length, and petticoats like Beauty’s, that reveal the shoes and ankles, were not just acceptable, but ubiquitous. Because shoes were always on display during this period, shoe fashions were just as varied as those of gowns or hats. Red shoes like Beauty’s were eye-catching on their own, but could be further accessorized with interchangeable “roses,” especially for formal wear (LM, 1784 303), or buckles. Beauty’s shoe buckles match her shoes, but buckles were also available in metals and with gems, depending on the wearer’s fancy.

Figure 16. Shoes similar to Beauty’s, in ivory, c. 1780s. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Novel

Figure 17.

The book Beauty is holding is as much part of her ensemble as her shawl or hat, and, like those accessories, it is an indicator of Beauty’s attention to trends. Also like her hat, her novel was popularized by and for women of fashion. Though novels were not considered high literature, that did not stop high society from reading them, or writing them, as the Duchess of Devonshire did.

All these pieces of Beauty’s outfit show that she is fashionable, but to understand how she became so, how she would be recognizable as such, why fashion was so culturally important, and how print so effectively communicated these ideas, requires closer examination of the context in which “Beauty in Search of Knowledge” was produced. A uniquely potent mix of landed aristocracy, deep-rooted class stratification, and rapid commercial expansion made eighteenth-century England an ideal breeding ground for consumer culture and fashion. Economic expansion and commercialization both fuelled and relied upon a market with constant demands for the new (McKendrick 316). This demand for novelty, combined with the middle class consumer’s desire to “believe in growth, in change” (316) and cultivate an “appetite for the new…for the getting and spending of money” (316) was essential to the economy in which fashionable trends thrived. The exclusivity of high-society taste makers, whose status and wealth allowed them to curate artistry in their attire that the middle classes could not achieve, created a constantly moving standard that was unattainable to the average Briton. The print industry played a key role in filling communication gaps between the trends set by the elites and the aspirations of the middle class.

Printed images like “Beauty,” as well as periodicals like The Lady’s Magazine, supplied up-to-date information on the latest trends. The periodical format was ideal for capturing the fashionable changes of the moment, referencing the changing details which expensive, time-consuming books could not hope to capture. In fact, a search for “fashion” in our titles yields no records about commercial fashion, suggesting that periodicals and ephemeral print works, not books, were the primary method of disseminating such information. The demand for frequent updates on fashion was so high that dozens of periodicals, including The Annual Present for the Ladies or a New and Fashionable Pocket Book, The Ladies' Mirror or Mental Companion, The Ladies’ Museum or Pocket Memorandum Book, and The Court and Royal Ladies’ Pocket Book were necessary to contain and convey the myriad details of attire that readers demanded (McKenzie 47). While well-to-do bourgeois women eagerly spent their new money on fashion plates and magazines that showed them hats popularized by the Duchess of Devonshire or gowns worn by the Duchess of Cumberland, and read with delight a magazine’s description of Marie-Antoinette’s newest morning gown, the glamour of the true elites remained ever elusive. The well-dressed and accessorized (but always slightly overdone) “Bourgeoise de Londre” could never become a true aristocrat, but the speed of production in print and the new wealth provided by a growing industrial economy meant she always had money to spend in the attempt.

“Beauty in Search of Knowledge” is itself an excellent example of this proliferation-via-imitation phenomenon. In its transformation from an original drawing by John Raphael Smith to a mass-produced commercial image, the picture has lost some of its vivacity and dynamism. The original chalk drawing limits through its very medium the capacity for mass distribution, while the new, printed form is less individualized, better suited to the fashion plate model designed for a commercial market. By expanding the reach of the image and the fashionable ideals it carries, the printing process also makes the knowledge the image carries more accessible. As McNeil points out, “Fashion can be conceptualized as a form of knowledge; one requires knowledge of what is in fashion to be a participant” (225), and it was this knowledge that periodicals and other ephemeral print works disseminated to the public. According to McNeil, "Fashionability . . . was both supported and propelled by its representation in print" (253), and while print supported fashionability, allowing the consumer to see and purchase print materials which depicted trends set in high society, it also propelled fashion by rapidly reproducing images of changing modes.

Prints like “Beauty in Search of Knowledge” were essential in helping the average bourgeoise woman understand not only the visible features of various trends in clothing, fabric, and accessories, but also how to interpret the social meanings of these features. Viewers would recognize these details such as Beauty’s broad black hat, airy white polonaise, and wide, curled hair and recognize her as a follower of fashion. Those conversant in the language of fashion could look at any person’s clothing and distinguish the status of the wearer at a glance. As long as elite trendsetters dictated the desirable yet ever-changing standard of fashion, there would always be some privileged knowledge on which members of the book trades could capitalize on, in selling to the middle classes. Precise details of fashion in clothing changed rapidly, but the print industry easily kept up. Speed, concise portrayal of complex ideas, and instant visual impact were all qualities print and fashion shared, and it was these qualities that made print and fashion perfect partners. Print worked in words (like the descriptions of changing trends in The Lady’s Magazine) which could be reproduced quickly, but it also worked in images, such as fashion plates and drawings like our own “Beauty in Search of Knowledge,” which conveyed the visual impact of detailed dress. This capacity to contain the complex details of changing modes, while also copying, reproducing, and distributing them, meant print was the perfect carrier of the culture of fashion.

Figure 18. A heavily accessorized “Bourgeoise de Londre,” c. 1780-1800. V&A.

WPHP Records Referenced

Cavendish, Georgiana (person)

Works Cited

“Full Dress and Deshabille.” The Lady’s Magazine, or entertaining companion for the fair sex, appropriated solely to their use and amusement, Vol. XI. G. Robinson, January 1780, p. 31, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/chi.79263555.

“Dress for August.” The Lady’s Magazine, or entertaining companion for the fair sex, appropriated solely to their use and amusement, Vol. XI. G. Robinson, August 1780, p. 404, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/chi.79263555.

“Dresses for January.” The Lady’s Magazine, or entertaining companion for the fair sex, appropriated solely to their use and amusement, Vol. XII. G. Robinson, January 1781, p. 16, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/chi.79263562.

“Fashion in High Life.” The Lady’s Magazine, or entertaining companion for the fair sex, appropriated solely to their use and amusement, Vol. XII. G. Robinson, February 1781, p. 63, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/chi.79263562.

Stanley, Charlotte. “Dress for March.” The Lady’s Magazine, or entertaining companion for the fair sex, appropriated solely to their use and amusement, Vol. XII. Robinson, March 1781, p. 153, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/chi.79263562.

“Dress for June.” The Lady’s Magazine, or entertaining companion for the fair sex, appropriated solely to their use and amusement, Vol. XII. G. Robinson, June 1781, p. 282, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/chi.79263562.

“Fashionable Dress at Paris.” The Lady’s Magazine, or entertaining companion for the fair sex, appropriated solely to their use and amusement, Vol. XIII. G. Robinson, April 1782, p. 195, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/chi.79263579.

“On Fashion.” The Lady’s Magazine, or entertaining companion for the fair sex, appropriated solely to their use and amusement, Vol. XIII. G. Robinson, August 1782, pp. 406-9, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/chi.79263579.

“Fashionable Dresses for 1783, by a lady of fashion.” The Lady’s Magazine, or entertaining companion for the fair sex, appropriated solely to their use and amusement, Vol. XIV. G. Robinson, March 1783, p. 121, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/chi.79263586.

“Fashionable Dresses for April 1783, by a lady of fashion.” The Lady’s Magazine, or entertaining companion for the fair sex, appropriated solely to their use and amusement, Vol. XIV. G. Robinson, April 1783, p. 187, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/chi.79263586.

“Fashionable Dresses for May and June 1784, by a lady of fashion.” The Lady’s Magazine, or entertaining companion for the fair sex, appropriated solely to their use and amusement, Vol. XV. G. Robinson, June 1784, p. 303, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/chi.79263593.

McKendrick, Neil et al. The Birth of a Consumer Society: The Commercialization of Eighteenth-century England. Indiana UP, 1982.

McNeil, Peter. “’Beauty in Search of Knowledge:’ Eighteenth Century Fashion and the World of Print.” Fashioning the early modern: dress, textiles, and innovation in Europe, 1500-1800, Oxford UP, 2017, pp. 223–53.

Waugh, Norah. The Cut of Women’s Clothes, 1600-1930. Theatre Arts Books, 1968.