Authored by: Isabelle Burrows

Edited by: Michelle Levy and Kandice Sharren

Submitted on: 01/19/2022

Citation: Burrows, Isabelle. "'Beauty in Search of Knowledge': Female Readership at the Eighteenth-Century Library." The Women's Print History Project, 19 January 2022, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/94.

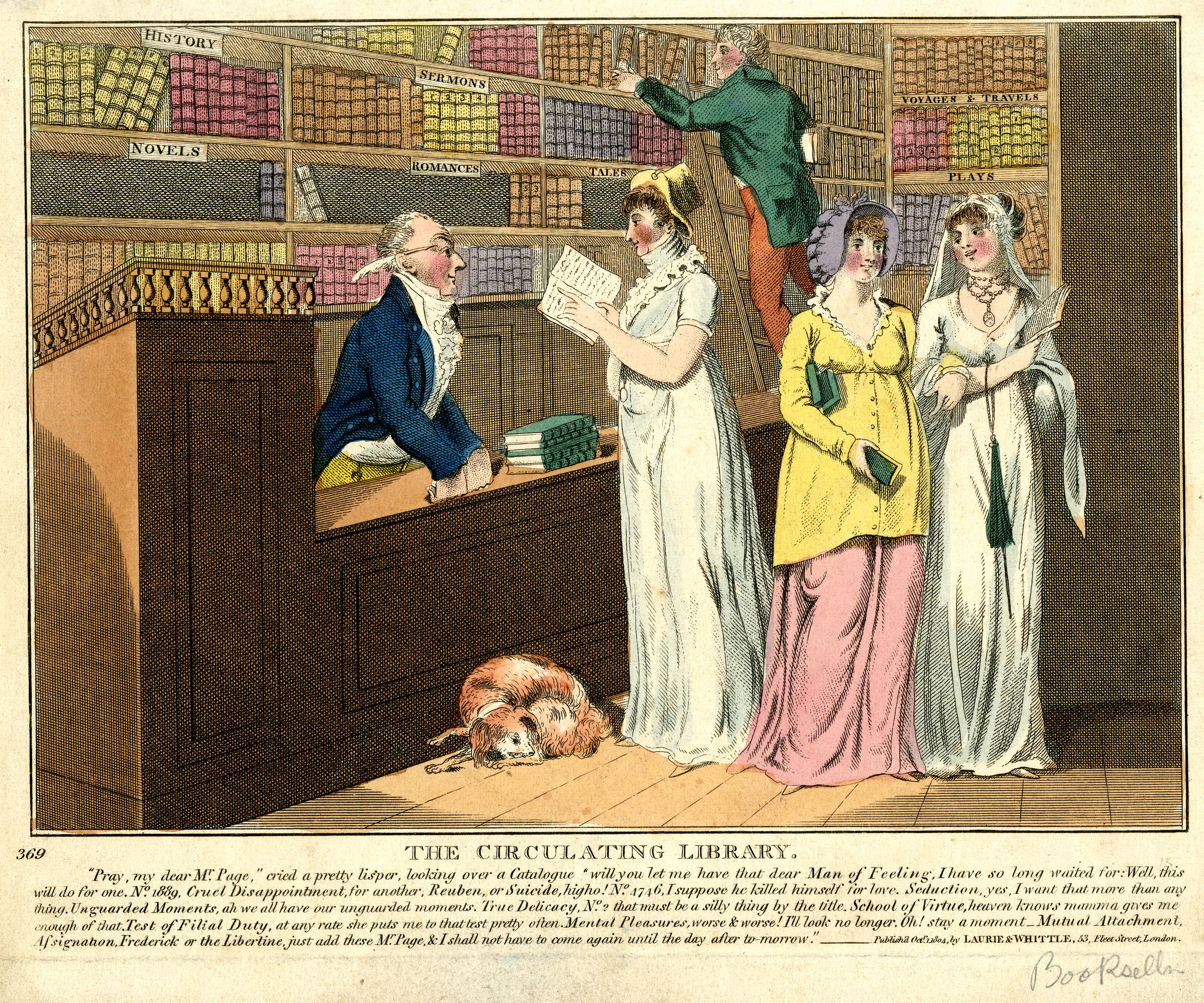

Figure 1. Detail from “Beauty in Search of Knowledge,” printed by Sayer and Bennett, 1782. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The first spotlight about our homepage illustration referenced the satire embedded in “Beauty in Search of Knowledge:” that a young woman patronizing a circulating library is more likely to be in search of superficial entertainment than meaningful knowledge. Libraries like the one depicted in the “Beauty” mezzotint distributed myriad printed materials, from books and pamphlets to prints and magazines on various topics. Since such topics often included the fashionable and the romantic, libraries were looked down on as purveyors of frivolous or even indecent materials. Circulating libraries were distributors of “all of the useless things in the world that could not be done without” (Sanditon, ch. 6 ), and as such frequently sold the accessories of sartorial fashion alongside the literature of fashionable society. The Beauty in the mezzotint is partaking of both. This second spotlight on “Beauty in Search of Knowledge” examines circulating libraries of the period, the accusations against them, and their relationship to female readership and authorship in order to expose and ultimately overturn the assumptions that underpin the critique implied in the print.

Because the WPHP collects information about editions, rather than copy-specific information, we do not account for titles that were held by circulating libraries, but that does not mean library information is unavailable in our data. One strategy for finding books that were distributed by libraries is to search for the term “circulating” in the imprint field of our “titles” records. The WPHP also contains information about many circulating library proprietors who doubled as booksellers and publishers. John Bell, William Lane, and Thomas Hookham, for example, simultaneously published, sold, and lent books. By the time of the printing of “Beauty in Search of Knowledge” in 1782, the commercial lending library had evolved beyond its origins in booksellers like the Widow Page, who, in 1674, “sold . . . All sorts of Histories to buy, or let out to read by the week” (Hamlyn 197n3) into a distinct entity. Libraries of the eighteenth century were divided into three broad categories: the private library, such as an aristocrat might have at home; the proprietary library, a kind of club co-owned and regulated by its members (Raven 246); and the commercial circulating library, a business venture supported by subscription fees from members. Commercial and proprietary libraries were the products of middle-class aspirations (Raven 245), and much like the fashionable clothing discussed in the previous article, these libraries, and the materials they distributed, served as indicators of the class to which their clientele belonged or aspired. Libraries often grew out of or next to other business ventures, as is the case in Austen’s Sanditon, in which Charlotte Heywood’s visit to the library equips her with “new parasols, new gloves and new brooches for her sisters and herself” (ch. 2). Beauty in our print is exiting (or entering) a commercial circulating library— the most controversial type of library at the time.

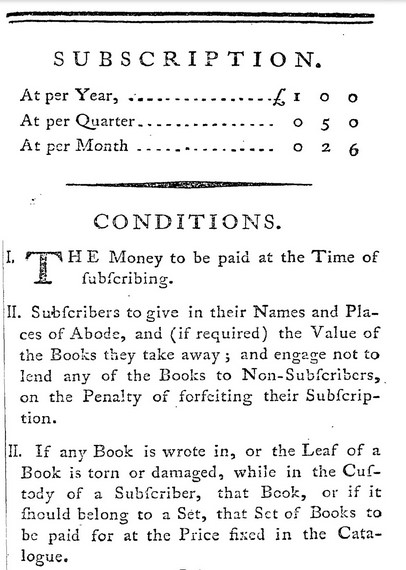

Figure 2. The terms of subscription for Ann Yearsley's Public Library, 1793. ECCO.

As commercial circulating libraries expanded in number and size throughout the eighteenth century (Kaufman 9–10), the ranks of their detractors grew just as quickly. Intellectual and moral authorities reacted critically to the “devotees of the circulating libraries,” whose “pass-time, or rather kill-time” of reading the libraries’ offerings could only be described as “a sort of beggarly day-dreaming” (Coleridge, I: 49n2). One critic despaired at the thought that modern readers bought books more “from fashion than from judgement” (Paterson 40), and even those who created the prints and novels which circulating libraries offered were eager to join the chorus. Opposition to libraries and their patrons was pervasive throughout the world of print material, as seen in the 1804 engraving below.

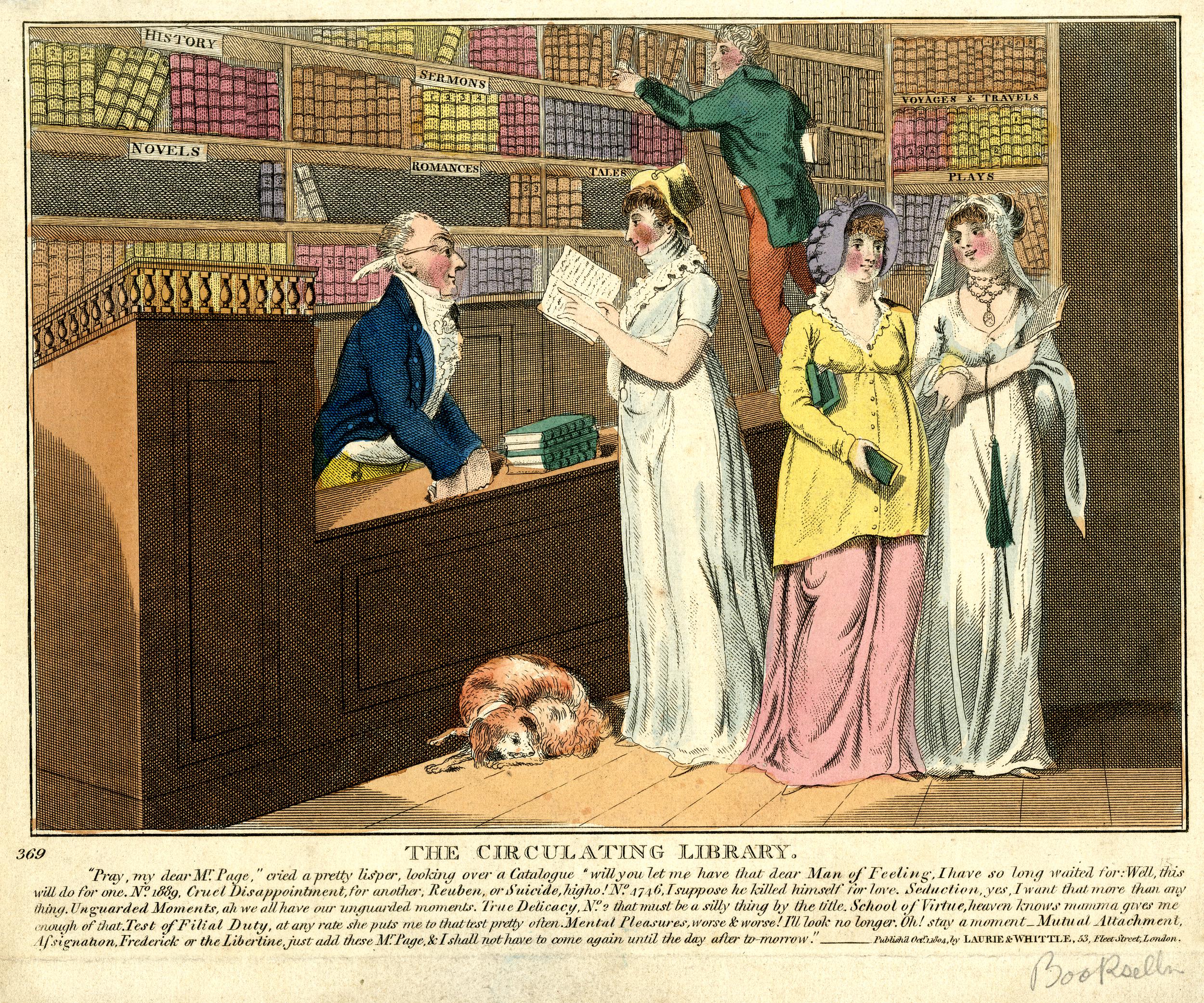

Figure 3. “The Circulating Library,” published by Laurie & Whittle, 1804. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The illustration plays upon stereotypes of female readers and circulating libraries, with the shelves full of “serious” works like sermons, history, and voyages and travels, whereas the sections for novels, romances, and tales have been emptied. This satire is compounded by the caption at the bottom, which first identifies the women patrons of the shop as “pretty lispers” (an appellation that infantilizes the women by associating their speech with the “prattle of the nursery” (On the Education of Daughters 9), and then pokes fun at the lady patron’s request for titles like “Reuben, or Suicide” which probably belonged to the same genre of “horrid” novels (919) whose unwholesome influence Jane Austen describes in Northanger Abbey. The criticisms levelled by the printmakers of “The Circulating Library” and “Beauty in Search of Knowledge” rely on the audience’s assumption that women readers didn’t have the intellectual fortitude to select virtuous reading materials, and might, through their poor choices, fall prey to frivolity or even immorality. The library’s role in increasing access to literature for middle class women raised concerns that this access would corrupt unformed minds with immoral material that women readers weren’t educated to recognize and weren’t prepared to resist. Intellectual and social elites worried about the degradation of morality, virtue, and taste if the production and consumption of literature got into the wrong hands (Kaufman 23).

Although the “Beauty in Search of Knowledge” mezzotint is satirical, it inadvertently reveals the positive aspects of library development. In visiting a circulating library and selecting her own reading material, Beauty is doing exactly what critics feared she would do. Female, middle-class, an adherent of commercial fashion, Beauty is a threat to conservative society, as she is intellectually autonomous. Those offended by women’s access to potentially salacious materials were possibly even more afraid that unsupervised access to the wide variety of reading materials which circulating libraries provided might further encourage female autonomy. However limited they might seem to the modern eye, the threats posed by the circulating library’s democratization of knowledge were enough to incite backlash by conservative authorities who wanted to keep the gates of the intellectual world firmly shut to women. Mary Wollstonecraft said that any threat to the “wisdom of antiquity” “raises an outcry- the state is in danger, if . . . they who, roused by the fight of human calamity, dare to attack human authority” (VoRW 13), and while most middle class women were not “roused by the fight of human calamity,” their access to newly commercialized literature certainly qualified as a disturbance of traditional wisdom. The ideological condemnation of novels, women readers and writers, and bourgeois tastelessness, rested on a fear of disruption caused by female independence.

Whatever critics liked to claim, libraries were patronized and novels were read by nearly everyone, male and female, middle and upper class. As Jan Fergus observes, the popular culture of the time may have identified novels and the libraries which sold them as strictly feminine business, but the evidence tells another story. In fact, “the tastes of male and female readers of all classes were not as different as many scholars have supposed—or as many eighteenth-century moralists alleged” (43). The 1799 borrowing record for Marshall’s Library in Bath reveals male customers no less august than the Prince of Wales himself (Kaufman, 21). He certainly didn’t limit himself to the respectable histories and sermons offered at the library, as his famous patronage of Austen’s Emma indicates. Even that enlightenment giant, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, cheerfully admits in his Confessions a fondness for the libraries of his youth, where he was plied by the librarian with books of “all kinds; good or bad” which he “perused… with avidity” (39). He recalls that his “reading, though frequently bad, had worn off my childish follies, and brought back my heart to nobler sentiments than my condition had inspired” (40), a refreshingly unpretentious expression of the improving qualities of libraries which other male intellectuals were too proud to make.

Library catalogues throughout the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries reveal that the tastes of all library patrons were highly varied. The list of available reading materials in Ann Yearsley’s 1793 catalogue, for instance, includes popular novels like Burney’s Evelina alongside Gibbons’ Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Thomas Hookham lists nine genres as his standard range of offerings, including plays, tracts, history, biography, novels, romances, poetry, drama, divinity, surgery, physic, and miscellanies. Our data in the WPHP supports this already diverse picture of contemporary reading tastes with highly original works, from Sarah Jackson’s The director: or, young woman's best companion, containing, above three hundred easy receipts in Cookery, Pastry, Preserving, Candying, Pickling, Collaring, Physick, and Surgery, distributed at John Fuller’s circulating library in Newgate Street, to A letter addressed to a female friend, by Mrs. Sage, the first English female aerial traveller; describing The General Appearance and Effects of her expedition with Mr. Lunardi's balloon by Letitia Ann Sage, which could be found at John Bell’s British Library in the Strand. Such an assortment indicates the wide range of readership and authorship which libraries fostered.

Far from limiting their stock to novels, circulating libraries offered books of all kinds alongside political and artistic prints like those depicted behind Beauty in the mezzotint. Printed figures were just as varied, as likely to depict lady’s fashions as satiric scenes, or both, as in the case of “Beauty in Search of Knowledge.” Prints were as important a medium for conveying information as text, since print ephemera could be reproduced much more quickly than books, and therefore could keep abreast of current events and trends. The figure prints in the window of the “Beauty” mezzotint, probably depicting new fashions and actresses in recent theatrical productions, quickly conveyed current tastes in an easily consumable form. The landscape prints featured alongside the figures provided a middle-class audience with access to information about current trends in tourism and art. An original Constable canvas might be beyond the reach of the average high-street library patron like Beauty, but prints of high art and the fashionable taste they represented were well within reach. A 1754 catalogue of printed materials from William and Cluer Dicey’s warehouse gives a good idea of the range of subjects that were common in print images of the eighteenth century. Their broad categories include “maps, prints, copy-books, drawing-books, histories, old ballads, broad sheet and other patterns, garlands, &c” but within each of these categories the variety is astounding, ranging from copper plates like Number 126, ‘the women fighting for the breeches: a comical scene, explained and versified” (19) to biblical stories like “The Angel Raphael discoursing with Adam in Paradise” (14). One print from the catalogue, pictured below, combines the crazes for classicism and continental tourism that characterized British culture in the eighteenth century with a fanciful depiction of “The Temple of Diana.” Whether their content was contemporary or historical, political or artistic, printed images, as engraver Thomas Bewick recalled, “must have given employment to a great number of artists… which served to enliven the circle in which they were admired” (Bewick 245–46).

Figure 4. Popular print of “The Temple of Diana” from the “Seven Wonders of the World” series listed on page 25 of the Cluer and Dicey Warehouse catalogue. Derived from a drawing by Maarten de Vos. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

“Beauty in Search of Knowledge” was probably intended as satire, but a cynical reading of the mezzotint would fail to account for the insightful details which the print contains. The search for knowledge depicted here is genuine. Commercial, middle-class institutions like circulating libraries should be studied and admired for their expansion of knowledge in eighteenth-century society and their role in creating new networks of intellectual communication.

WPHP Entries Referenced

John Bell (firm)

William Lane (firm)

Thomas Hookham (firm)

Austen, Jane (person, author)

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor (person, author)

Biographia literaria (title)

Wollstonecraft, Mary (person, author)

Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (title)

Vindication of the Rights of Woman (title)

Northanger Abbey (title)

Emma (title)

Ann Yearsley (firm)

Burney, Frances (person, author)

Evelina (title)

Jackson, Sarah (person, author)

John Fuller (firm)

Sage, Letitia Ann (person, author)

Works Cited

Austen, Jane. Sanditon. Project Gutenberg eBook, 2013. https://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks/fr008641.html. Accessed 17 January 2022.

Austen, Jane. Northanger Abbey. The Complete Novels of Jane Austen, pp. 903–1029. Quarto Publishing, 2016.

Bewick, Thomas. A Memoir of Thomas Bewick, Written by Himself. Longman, 1862.

A Catalogue of Hookham’s Circulating Library. T. Bretell, 1829.

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. Biographia literaria, vol. I. Rest Fenner, 1817.

Dicey, William and Cluer. A catalogue of maps, prints, copy-books, drawing-books, &c. histories, old ballads, Broadsheet and other Patterns, Garlands, &c. London, 1754.

Fergus, Jan. Provincial Readers in Eighteenth-Century England. Oxford UP, 2007.

Hamlyn, Hilda M. “Eighteenth-century Circulating Libraries in England.” The Library, vol. 5-I, no. 3-4, December 1946, pp. 197–222.

Kaufman, Paul. “The Community Library: A Chapter in English Social History.” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 57, no. 7, 1967, pp. 1–67.

Paterson, Samuel. Joineriana: or, the Book of Scraps, Vol I. Joseph Johnson, 1772.

Raven, James. “Libraries for Sociability: The Advance of the Subscription Library.” The Cambridge History of Libraries in Britain and Ireland, edited by Giles Mandelbrote and K. A. Manley, vol. 2, Cambridge UP, 2006, pp. 239–63.

Rousseau, Jean Jacques. The Confessions of Jean Jacques Rousseau, now first completely translated into English, vol. I. Privately printed for members of the Aldus Society, 1903.

Wollstonecraft, Mary. A Vindication of the Rights of Woman; with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects. J. Stockdale, 1793.

Wollstonecraft, Mary. Thoughts on the Education of Daughters. J. Johnson, 1787.

Yearsley, Ann. Catalogue of the books, tracts, &c. contained in Ann Yearsley's Public Library, No.4, Crescent, Hotwells. Ann Yearsley, 1793.