This post is part of our By Our Books: Bibliography in the WPHP Spotlight Series, which will run through July 2023. This series attends to the bibliographical fields of the WPHP title records, tracing the history of our thinking about our descriptive practices and how they are informed by the sources available to us and by our feminist ambition to recognize and reconstruct women’s labour in print, broadly conceived.

Authored by: Kate Moffatt

Edited by: Michelle Levy and Kandice Sharren

Submitted on: 08/02/2023

Citation: Moffatt, Kate. "Colophons Count." The Women's Print History Project, 2 August 2023, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/128.

On the last page of Mary Pilkington’s Marvellous Adventures, or, The Vicissitudes of a Cat: In Which are Sketches of the Characters of the Different Young Ladies and Gentlemen into Whose Hands Gramlkin Came (1802) there are two short lines of print near the bottom edge, reading

W. Blackader, Printer,

10, Took’s Court, Chancery Lane.

These two lines are a colophon. During our period, a colophon is a small, imprint-like line or two containing information about the printer of a book, typically located on the verso of a title page or on the last page. Prior to the eighteenth century, however, the definition of the term ‘colophon’ was less stable, and it often held a wide variety of information, most of which we would expect to find in an imprint in the eighteenth century. In Shef Rogers’ “Imprints, Imprimaturs, and Copyright Pages” in Dennis Duncan and Adam Smyth’s Book Parts (2019), Rogers outlines the history of the colophon: “From the mid-fifteenth century [...] the colophon became a more formal collocation of essential information to indicate who had published a work, where it could be purchased, and, because the book was normally sold unbound in sheets, a statement called the register that told the binder the order of the sheets for binding” (54). Rogers goes on to trace how the information in fifteenth-century colophons began to be distributed across printed materials in the following centuries; by the early sixteenth century, title page imprints had become more common, and by the seventeenth, colophons had been “supplanted by imprints” (55).

Rogers’ description of the colophon’s varying elements throughout history is helpful for understanding how changeable this particular book part has continued to be—but our data suggests that the shift from colophons to imprints was still not as tidy as it may seem. While Rogers acknowledges that colophons have “remained a feature of fine press printing, to acknowledge the book’s makers, to highlight the quality of the materials used to make the book, and, in limited editions, to record the book’s place in the numbered series” (55), our bibliographical work for the WPHP establishes that the colophon survived intact beyond the seventeenth century. In fact, our colophon data demonstrates that the long eighteenth century presents an interesting period in which to consider the inclusion of printers’ information on books.

The colophon was delightfully unpredictable in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries—a printer might include a colophon on some of the works they printed, but not all of them, for example—but they are present on a significant portion of printed materials. Searches in the WPHP for “printer” and “printed by” in the colophon field reveal more than 2300 titles with colophons. But the colophon also, I would argue, gained consistency during this period. The colophons we are working with always contain printer information, including, albeit in varying combinations, a name, trade address, and the city of operation and printing.

The colophon field in the WPHP transcribes the colophons we find on the physical and digital facsimiles of our titles. It was a field added to the WPHP in 2016 when I discovered, while final-checking some of our English Novel titles against digital facsimiles, that printer information was consistently included on the verso of title pages or on the last page of a book. These often became the means for determining the printer of a work, which allowed me to add that firm to the database and attach it to the title in the firms field, and I wanted to capture where that information came from on the book in our title records. With no dedicated field for colophons at that stage of the project, I added them to our “Notes” until a conversation with the project director, Michelle Levy, and project manager, Kandice Sharren, resulted in the decision to add a “Colophon” field to our title records, allowing us to more strategically capture the information that was in the colophon.

Rogers’ suggestion that the colophon was supplanted by the imprint illustrates how such scholarly assumptions affected—and continue to affect—our data model. If colophons were replaced with imprints before our period, there was no need to include a field to capture that information. But in looking closely at our objects of study, which takes us beyond the title page and the information included there, we were able to see that the colophon did not quietly disappear. They appear on at least 10 percent of our titles—a number that would likely be higher if we had access to digitizations for every book in the database, more RA labour, and the ability to search for colophons in our resources. What our data suggests, in fact, is that colophons are ubiquitous.

Colophons and imprints have a complicated history, as shown above, and it is no simpler in the WPHP data. Printer information, when it is included on a book, can appear in any of the following places: on the verso of the title page, on the verso of the page before the title page, on the last page of the book, on the verso of the last page of the book; and in any of the following combinations: only in the imprint, in the imprint and in a single colophon (any location), in the imprint and in multiple colophons (multiple locations), only in the colophon. The WPHP captures any and all information included in the imprint and colophon(s) in a book.

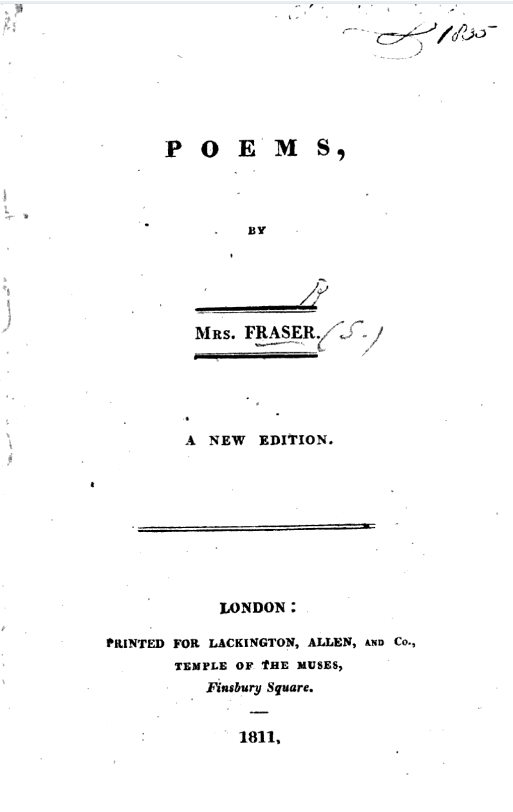

Figure 1. Title page of Susan Fraser's Poems (1811), which features an imprint without any identifying printer information. Google Books.

Colophons can hold additional information about a printer that is not included in the imprint, such as full names or addresses, and perhaps even more importantly, can name a printer who is absent from the imprint altogether. This means our colophon field allows us to capture those printers who otherwise go unseen in databases and resources. Most of our resources, including the field-changing English Short Title Catalogue and the Eighteenth Century Collections Online database, do not capture colophon information in their metadata with anything approaching consistency—it is the imprint that is considered one of the best sources for identifying the tradespeople involved in the making of the book and so it is the imprint that is captured in metadata far more reliably. The problem, of course, is that the imprint does not always include the printer. One such example in the WPHP is printer Elizabeth Blackader, who took over her husband Walter’s business (the “W. Blackader” named in the first colophon example of this Spotlight) in 1804 until her retirement in 1817. She printed the 1811 “new edition” of Susan Fraser’s Poems. The imprint on the title page (figure 1) indicates that the work was

PRINTED FOR LACKINGTON, ALLEN, AND CO.,

TEMPLE OF THE MUSES,

Finsbury Square.

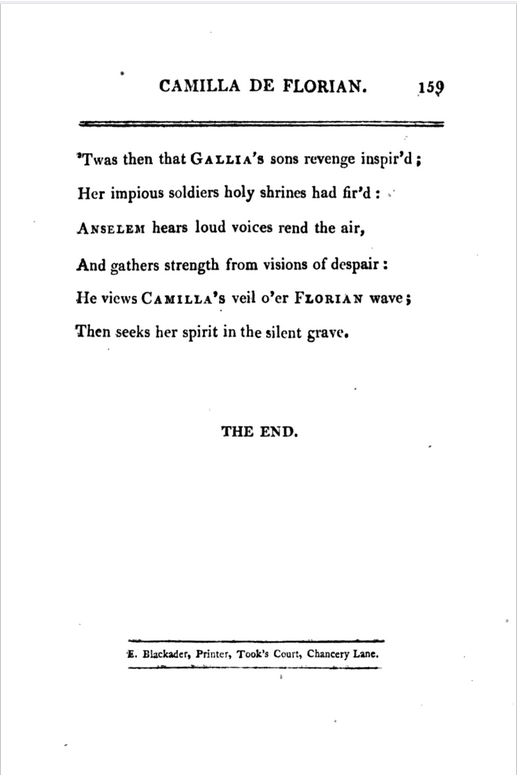

There is no mention of a printer—only that it was published for Lackington, Allen, and Co. On the last page of the book, however, there is a colophon, which reads “E. Blackader, Printer, Took’s Court, Chancery Lane" (figure 2).

Figure 2. Last page of Susan Fraser's Poems (1811), which includes a colophon naming "E. Blackader" as the printer. Google Books.

The “E.” in “E. Blackader” stands for Elizabeth, and her involvement in producing this book is only captured in its colophon. She is not named in the metadata of the British Library record, or in the Google Books record. Without inclusion of the colophon in our database, which results in her firm and person records being linked to this title, Elizabeth Blackader would remain invisible, and it would be impossible for us to connect her to the other titles she printed (there are currently eleven in total in the WPHP).

Imprints have been, and remain, a main source of information for identifying who published, printed, and sold a book during this period. As Isabella Eist outlines in her spotlight on our firms and imprint fields, imprints are clearly visible on title pages and contain identifying information about the businesses and the individuals who ran them. But what about the individuals whose contribution to a book’s production are captured beyond the title page of the book itself, just not where we expect to find it? Further research on the colophon has the potential to radically change the landscape of eighteenth and early nineteenth century printing as we know it. If searching a printer’s name in the ESTC returns one hundred titles based on a search of the imprint field, how many names might it return if the ESTC included searchable colophon metadata. My PhD research focuses on the visibility of women in the eighteenth-century book trades, and their (in)visibility bibliographically. The colophon is one space in which women, and printers more generally, have been bibliographically and archivally elided. Including the colophon in the WPHP is one such attempt to capture a book part that has the potential to allow for a different, and fuller, view of printers’ output during the period.

WPHP Records Referenced

Mary Pilkington (person, author)

Elizabeth Blackader (firm)

Walter Blackader (firm)

Susan Fraser (person, author)

Poems (title)

Lackington, Allen, and Co (firm)

'"Printed by—": Imprints and Firms in the WPHP" (spotlight by Isabella Eist)

Works Cited

Duncan, Dennis and Adam Smyth, eds. Book Parts. Oxford University Press, 2019.

Rogers, Shef. “Imprints, Imprimaturs, and Copyright Pages.” Book Parts, ed. Dennis Duncan and Adam Smyth, Oxford University Press, 2019, pp. 53–64.