This post is part of our Black Women's and Abolitionist Print History Spotlight Series, which will run between 19 June and 31 July 2020. Spotlights in this series focus on our work to find Black women who were active participants in the book trades during our period, to acknowledge the ways in which white female abolitionists exploited print’s powerful potential for eliminating slavery, and to revisit the lives and books published by well-known Black female authors.

Authored by: Kate Moffatt

Edited by: Michelle Levy and Kandice Sharren

Submitted on: 06/25/2020

Citation: Moffatt, Kate. "The Search for Firm Evidence: Uncovering Ann Sancho, Bookseller." The Women's Print History Project, 25 June 2020, www.womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/20.

This post was edited on June 6, 2024 to correct the identification of Frances Crewe Philips (not Frances Anne Crewe) as editor of Ignatius Sancho's Letters, and to correct Ann Sancho's place of birth.

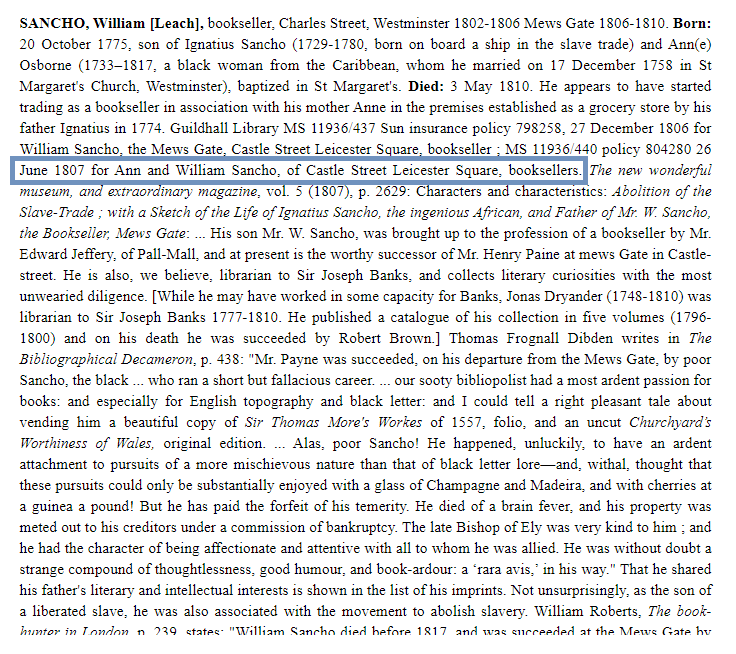

Figure 1. Screenshot of William Sancho's entry in Ian Maxted's The Exeter Working Papers website (my emphasis).

Figure 1. Screenshot of William Sancho's entry in Ian Maxted's The Exeter Working Papers website (my emphasis).

While combing through Ian Maxted’s Exeter Working Papers in Book History website early last year, I came across an entry for a Mr. William Sancho. The entry for “SANCHO, William [Leach]” is in no way suggestive of a woman’s involvement in the book trades, but the rather hefty paragraph of information within it seemed promising. I was looking specifically for references to women publishers, printers, and booksellers, a task made difficult by the fact that none of our firm resources include gender data in their records. Finding women involved in the book trades requires us to read systematically through every entry of our various resources in an effort to find traces of women's involvement in the business of books—a task that is, as of the writing of this spotlight in June 2020, still ongoing. Women occasionally have their own entries, but many do not, and we must search for the evidence of women’s involvement that is buried in the entries for their husbands, business partners, or relatives.

Such was the case with Mrs. Ann Sancho, née Osborne, a Black woman born in London to John and Mary Osborne of Bond Street, London, and christened 26 September at the Church of St. Mary, Whitechapel, who married Ignatius Sancho on 17 December 1758 (Caretta, ODNB). Tucked a few sentences deep into William Sancho’s entry, we learn that “[William] appears to have started trading as a bookseller in association with his mother Anne in the premises established as a grocery store by his father Ignatius in 1774.” The entry also includes their joint insurance policy, listed as “MS 11936/440 policy 804280 26 June 1807 for Ann and William Sancho, of Castle Street Leicester Square, booksellers.”

Although Ann Sancho does not have her own entry in the Exeter Working Papers, these passing mentions of her involvement in the book trades merit the inclusion of Firm and Person Records for her in the WPHP, even before ascertaining the titles she sold or published. We make a point of creating records for any and all women publishers, booksellers, and printers we come across from our period, regardless of how many titles, if any, are attached to their names. Ann Sancho, as it turns out, is yet to have any titles associated with her records, as we have not yet been able to find any with her name in the imprint. Including these women, however, works two-fold for our efforts to uncover evidence of women’s involvement in the book trades: it allows us to paint a fuller picture of the women involved, and provides a record from which we can direct further research.

Figure 2. Portrait of Ignatius Sancho by Thomas Gainsborough, 1768, held by the National Gallery of Canada.

In the case of Ann Sancho, wife of the famous Ignatius Sancho and mother to William Sancho, who was known as the “negro bookseller” in the Mews (William Roberts, The Book-Hunter in London 1895) and is thought to be “the first Black publisher in the Western world” (British Library), we have more information than for many of the other tradeswomen in the database. We not only have the address of her place of business in the Mews, but also her birth and death dates, her place of birth and death, her full married and maiden names, and at least one year where we know she was active in the bookselling business: 1807, the year the insurance policy was created with her name on it. Our access to this information is visible in part because Ignatius Sancho was, and is, widely known as an educated Black ‘man of letters’. He was well-connected in London, with the visitors to his grocer’s shop being, as Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina points out, “astonishing for a grocer and his family, let alone a black one. The Montagues and their friends visited Sancho’s store. David Garrick, the most famous actor of the century, was a close friend . . . Gainsborough painted Sancho’s portrait. Samuel Johnson, widely considered the greatest mind of the century, planned to write his biography” (106). He occupied an exceptional position. Gerzina argues that, “as quite possibly the only middle-class, well-connected, and highly literate black man in all of Britain, his very visible existence could and did affect how thousands of people in that country viewed Africans and slavery” (107). In the first edition of his posthumously-published letters, Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho (1782), the anonymous editor—Frances Crewe Philips (not to be confused with Frances Anne Crewe, and thank you to Lawrence Evalyn and Jack Orchard for the correction)—prefaced the edition with,

[The Editor’s] motives for laying [these letters] before the publick were, the desire of shewing that an untutored African may possess abilities equal to an European, and the still superior motive, of wishing to serve his worthy family. And she is happy in thus publicly acknowledging she has not found the world inattentive to the voice of obscure merit. (i–ii)

Ignatius Sancho’s exceptional status and resulting visibility, both during his time and now as a subject of recent scholarship, must be acknowledged for the access we have to data regarding Ann Sancho, including her race. Like gender, most resources do not account for racial data. Indeed, Ann and William Sancho are the only Black booksellers we know about in the WPHP. The limited visibility of racial data makes the recovery of Black tradeswomen difficult—even when, as Ann Sancho shows us, they are attached to visible men.

As a result, information about Ann Sancho’s bookselling business with her son is limited. The British Book Trade Index lists an entry only for “Sancho, ---”, and the entry notes, “A ‘negro’. Son of Ignatius Sancho, grocer and oilman. Briefly a bookseller in Thomas Payne’s shop. Died by 1814,” a description clearly marking it as about William. Neither William nor Ann Sancho appear in Philip A.H. Brown’s London Publishers and Printers c. 1800—1870 (1982). She is mentioned briefly in several accounts of Ignatius Sancho’s life, where they reference her marriage to Ignatius and their seven children (Wikipedia; The Grub Street Project; Westminster Abbey); the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and the British Library both mention that “the couple opened a grocery store in Westminster” (BL)—which would later become the first premises of William Sancho’s bookselling business—but there is no mention of the bookselling business itself. In Joseph Jekyll’s 1782 Life of Ignatius Sancho, Jekyll writes that Ann Sancho (named only as Ignatius’s “matrimonial connexion”) was “a very deserving young woman of West-Indian origin,” even though, as Brycchan Carey points out, it appears “unlikely that Jekyll had any more than a passing acquaintance with the Sancho family” (4). Some letters in Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho do provide more information about Ann Sancho, but none about her work in the book trades, as the business began after Ignatius Sancho’s death.

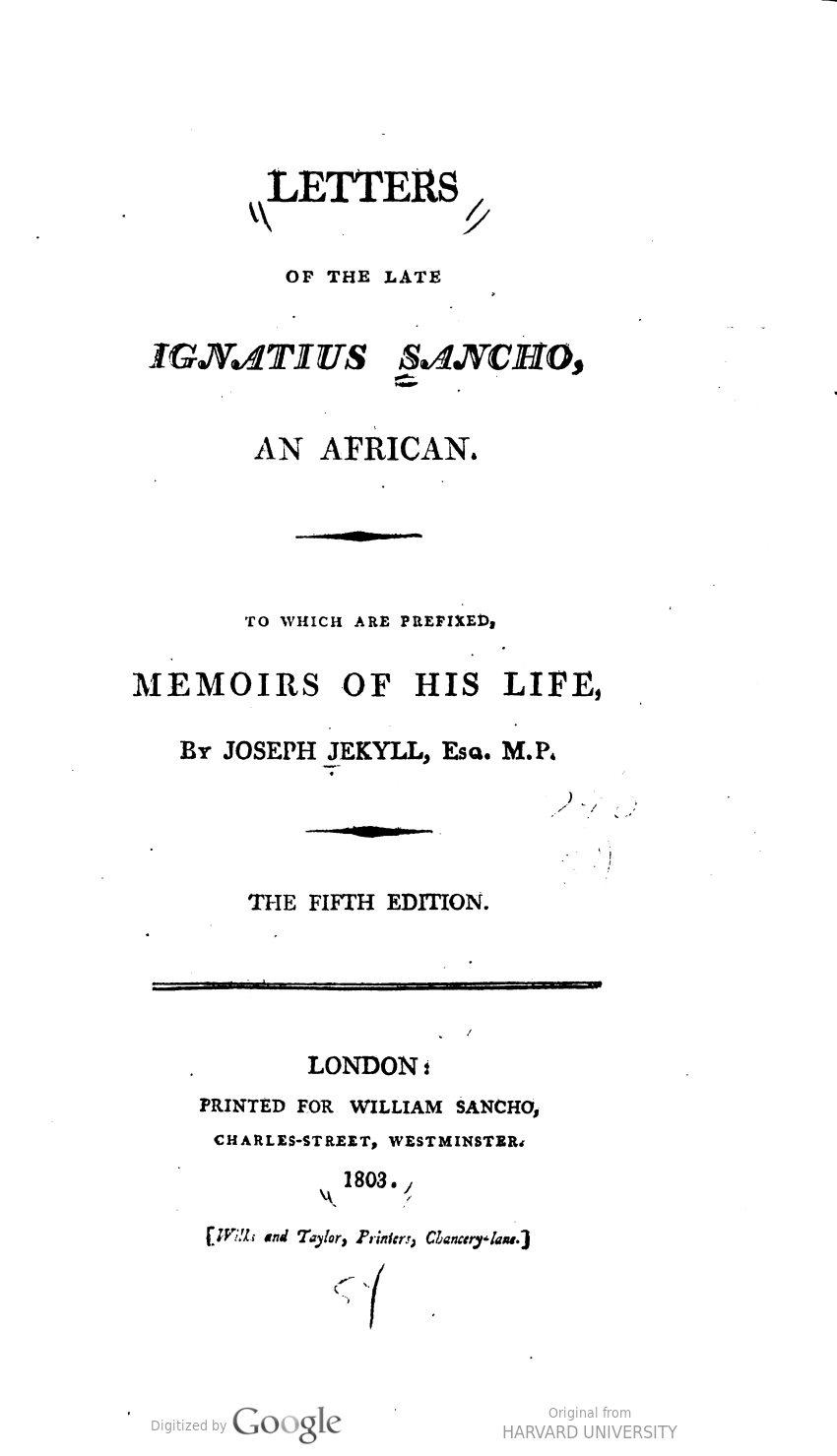

Title page of the fifth edition of Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho (1803), published by William Sancho. Courtesy of HathiTrust Digital Library.

When scholarship and existing resources fail to produce the information we collect for the database, we turn to imprints, searching for the names of publishers, printers, or booksellers in sources such as the Nineteenth Century Collections Online database, the Hathi Trust Digital Library, or the British Library online catalogue. In Ann Sancho’s case, however, even a search for imprints with the name “Sancho” in them reveals little that is useful. Multiple books have imprints that name “Wm. Sancho”, “W. Sancho”, or “William Sancho,” cementing her son’s involvement in the book trades—he even published the fifth edition of Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho, pictured above—but there are no results for “Ann Sancho”, “Anne Sancho”, “A. Sancho”, or “Mrs. Sancho.” The Exeter Working Papers entry for Williams Sancho lists a single imprint containing only the surname “Sancho”, Am I not a friend and a brother? : a sermon preached at the Free Chapel, West Street, St. Giles's, on Wednesday evening June 15th, 1808 : for the benefit of the African and Asiatic Society and published at the request of the committee for the benefit of the institution by William Gurney, but a digitized version is unavailable. According to the entry, the imprint reads, “London: Printed by W. Nicholson, for Hatchard, Ogle, Williams and Smith, Button, and Sancho, 1808.” This single book could potentially be attributed to Ann or William Sancho, as it does not indicate a first name or initial, and was printed the year after the 1807 joint insurance policy was created. Given the lack of concrete evidence, however, this title cannot be attributed with any certainty to Ann Sancho. There are a few possible explanations for why Ann Sancho does not appear in imprints: one possibility is that she was one of the many women involved in book production, particularly in family businesses, but not necessarily included in imprints (Hannah Barker). It is also possible, of course, that Ann Sancho was working with her son and that imprints with his name mask her involvement, a situation that likely holds true for many women. However, without more evidence of her involvement, we do not attribute those particular titles to her. As a result, although Ann Sancho has a record as a female firm and very well may have been involved in the production of the titles listed above, we have no titles associated with her in the WPHP.

Our unsuccessful search for imprints naming Ann Sancho, which would provide us with concrete evidence of her involvement as well as offering some indication of her years of activity, is not atypical. Alice Murray, a Dublin bookseller, is similarly unaccounted for in our usual resources. Listed in A Dictionary of Members of the Dublin Book Trade 1550-1800, we have her place of business and years of active trading, but imprints including her name have eluded us, leaving her record similarly unassociated with any titles. Finding biographical information about her has also proved difficult, which is also typical for women whose businesses are not well-documented (and sometimes even for those who are). Alice Murray’s Person Record will remain skeletal until further information about her can be found. Similar circumstances surround many other women-run firms in the database: the stationer Mrs. Vertue, first name unknown, was found buried and unnamed in the entry for Mr. Samuel Goadby in the Exeter Working Papers in Book History. While she is listed in the British Book Trade Index as trading under the name “Vertue and Goadby,” allowing us to associate two titles in the database with her firm (A letter from…; To the memory…), we have very little further biographical information for her Person Record than what is offered in the Samuel Goadby entry in the Exeter Working Papers, and no further business details than what the BBTI entry contains. (If you’re interested in reading further about the elusive Mrs. Vertue, see the book chapter by Kandice Sharren and myself about discovering women in the book trades)

The visibility of women in the book trades is complex: they were involved at all levels and in all roles, including those that the WPHP does not account for, such as papermakers, bookbinders, and typesetters, given that we focus our data collection on the information that is recoverable through imprints and colophons, which is usually limited to the roles of printer, publisher and bookseller. Even for those women in these roles, visibility in existing resources can be severely limited and affected by a number of outside influences—Ann Sancho’s race, made obvious by existing scholarship about her husband, for example, actually rendered her more visible. As illustrated in this spotlight, women can be hidden within entries for their husbands, relatives, or business partners—and women would sometimes continue to publish under their husband’s name following his death, or publish with their surname and no first name or initial to hint at their identity. By creating person and firm records for these women, we hope to make possible a future and fuller recovery of women like Ann Sancho, Alice Murray, and Mrs. Vertue.

We will be chatting about the process of discovering and uncovering women-run firms, the challenges we face, and how we are working to overcome them in Episode 2 of The WPHP Monthly Mercury. Tune in next month, on July 15, 2020, to hear more about Mrs. Ann Sancho and the adventures of the firm records in The Women’s Print History Project.

WPHP Records Referenced

Sancho, Ann (person)

Ann and William Sancho (firm, bookseller)

Sancho, Ignatius (person, author)

William Sancho (firm, bookseller)

Letters of the late Ignatius Sancho (1782) (title)

Philips, Frances Crewe (person, editor)

Jekyll, Joseph (person, author)

Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho (1803) (title)

Murray, Alice (person)

Mrs. Vertue & Samuel Goadby (firm, bookseller and printer)

A letter from the Lord Bishop of London… (title)

To the memory of the Revd. Mr. Mordecai Andrews (title)

Mrs. Vertue (firm, printer and bookseller)

Works Cited

Barker, Hannah. "Women, work and the industrial revolution: female involvement in the English printing trades, c. 1700–1840." Gender in Eighteenth-Century England: Roles, Representations and Responsibilities, edited by Hannah Barker and Elaine Chalus, Longman, 1997, pp. 81-100.

British Book Trade Index. http://bbti.bodleian.ox.ac.uk.

Brown, Philip A. H. London Publishers and Printers, c. 1800-1870. British Library, 1982.

Carey, Brycchan. “‘The extraordinary Negro’: Ignatius Sancho, Joseph Jekyll, and the Problem of Biography.” British Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies, no. 26, 2003, pp. 1-14, https://brycchancarey.com/Carey_BJECS_2003.pdf. Accessed 17 June 2020.

Carretta, Vincent. "Sancho, (Charles) Ignatius (1729?–1780), author." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford UP, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/24609.

“Catalogues and Collections,” British Library. https://www.bl.uk/catalogues-and-collections/catalogues.

‘(Charles) Ignatius Sancho (1729–1780),’ The Grub Street Project. https://grubstreetproject.net/people/11018/.

English Short Title Catalogue. http://estc.bl.uk.

Gerzina, Gretchen Holbrook. “Ignatius Sancho: A Renaissance Black Man in Eighteenth-Century England.” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, vol. 21, 1998, pp. 106–107.

Hathi Trust Digital Library. https://www.hathitrust.org/.

“Ignatius Sancho,” British Library. https://www.bl.uk/people/ignatius-sancho.

“Ignatius Sancho: Writer, Musician, Playwright and Abolitionist,” Westminster Abbey. https://www.westminster-abbey.org/abbey-commemorations/commemorations/ignatius-sancho. Accessed 17 June 2020.

Maxted, Ian, ed. Exeter Working Papers in Book History. https://bookhistory.blogspot.com/.

Nineteenth-Century Collections Online. https://www.gale.com/primary-sources/nineteenth-century-collections-online.

Pollard, Mary, ed. Dictionary for Members of the Dublin Book Trade, 1550-1800. Bibliographical Society, 2000.

Roberts, William. The Book-Hunter in London: Historical and other Studies of Collectors and Collecting with numerous portraits and illustrations. Elliot Stock, 1895.

“Sancho, ---,” British Book Trade Index. http://bbti.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/details/?traderid=60724. Accessed 25 June 2020.

Sancho, Ignatius. Letters of the late Ignatius Sancho, an African. In two volumes. To which are prefixed, Memoirs of his Life. Frances Anne Crewe, ed., and Joseph Jekyll, Memoirs. Printed for the subscribers, 1782.

“Sancho, Ignatius,” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ignatius_Sancho. Accessed 17 June 2020.

“The only surviving manuscript letters of Ignatius Sancho.” British Library. https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/the-only-surviving-manuscript-letters-of-ignatius-sancho. Accessed 25 June 2020.

“Vertue, Mrs,” British Book Trade Index. http://bbti.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/details/?traderid=71672.

Further Reading

Caretta, Vincent. “Three West Indian Writers of the 1780s Revisited and Revised.” Research in African Literatures, vol. 29, no. 4, 1998, pp. 73-87.

Hanley, Ryan. Beyond Slavery and Abolition: Black British Writing, c. 1770-1830. Cambridge University Press, 2019.

House, Khara. “Ignatius Sancho’s Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho, An African.” The Explicator, vol. 71, no. 3, 2013, pp. 195–98.

Sharren, Kandice, and Kate Moffatt. “From Print to Process: Gender, Creative-Adjacent Labour and the Women’s Print History Project.” Women In Print: Distribution, and Consumption: Volume 2, edited by Helen S. Williams, Peter Lang, 2022.