This post is part of our Black Women's and Abolitionist Print History Spotlight Series, which will run between 19 June and 31 July 2020. Spotlights in this series focus on our work to find Black women who were active participants in the book trades during our period, to acknowledge the ways in which white female abolitionists exploited print’s powerful potential for eliminating slavery, and to revisit the lives and books published by well-known Black female authors.

Authored by: Michelle Levy

Edited by: Amanda Law and Kandice Sharren

Submitted on: 07/24/2020

Citation: Levy, Michelle. “Maria W. Stewart, Activist for ‘African rights and liberty’.” The Women’s Print History Project. 24 July, 2020, www.womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/29.

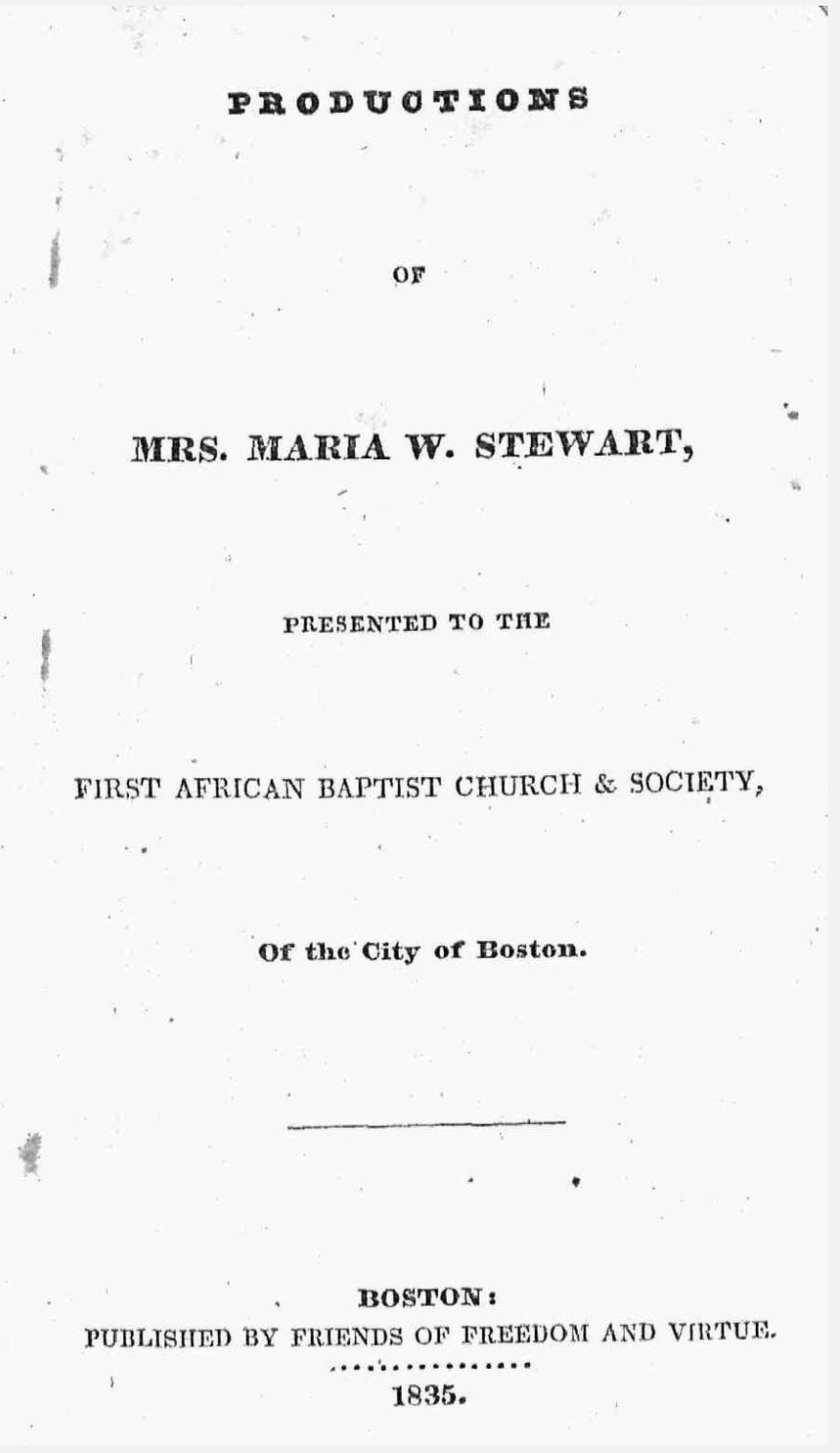

Figure 1. Productions of Mrs. Maria W. Stewart title page. Sabin Americana, Gale.

Maria W. Stewart (née Miller; 1803–1879), born a free woman in Hartford, Connecticut, was the first African American woman to lecture publicly on political, religious and racial issues, and the first to leave a record of her thoughts and speeches. Her publications provide important access to the voice of an African-American woman in the early 1830s, at the birth of the Abolitionist movement in Boston. A taste for the forceful and uncompromising nature of Stewart’s speeches may be gleaned in this excerpt from her third address of 27 February 1833, where she offers a devastating account of the exploitation of Native and Black Americans at the hands of white colonists and slave owners:

The unfriendly whites first drove the native American from his much loved home. Then they stole our fathers from their peaceful and quiet dwellings, and brought them hither, and made bond-men and bond-women of them and their little ones; they have obliged our brethren to labor, kept them in utter ignorance, nourished them in vice, and raised them in degradation; and now that we have enriched their soil, and filled their coffers, they say that we are not capable of becoming like white men, and that we never can rise to respectability in this country. They would drive us to a strange land. But before I go, the bayonet shall pierce me through. African rights and liberty is a subject that ought to fire the breast of every free man of color in these United States, and excite in his bosom a lively, deep, decided and heart-felt interest. (71–72)

Here Stewart denounces the calls to forcibly deport African-Americans to Africa, schemes for which survived well beyond the end of the Civil War. She further insists, some 35 years before they were granted citizenship, that Blacks are Americans and entitled to the civil and political rights afforded to whites.

Stewart recounts her early life in her twelve-page pamphlet, Religion and the Pure Principles of Morality, the Sure Foundation on Which We Must Build, first printed in 1831 and reprinted in 1835 as part of the Productions of Mrs. Maria W. Stewart: presented to the First African Baptist Church & Society of the city of Boston:

I was born in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1803; was left an orphan at five years of age; was bound out in a clergyman's family; had the seeds of piety and virtue early sown in my mind; but was deprived of the advantages of education, though my soul thirsted for knowledge. Left them at 15 years of age; attended Sabbath Schools until I was 20; in 1826, was married to James W.Stewart; was left a widow in 1829; was, as I humbly hope and trust, brought to the knowledge of the truth, as it is in Jesus, in 1830; in 1831, made a public profession of my faith in Christ. (3-4)

What Stewart does not relate is that, after the death of her husband, the young widow was cheated out of her inheritance by unscrupulous white businessmen (Richardson, “Stewart, Maria W.”). In need of resources, and inspired by her recent conversion as well as the emerging African American and abolitionist movements in Boston, Stewart began to address the public, both in written and oral forms.

In her first pamphlet, Stewart directly asserts equality between Blacks and whites, reminding her readers that “according to the Constitution of these United States, he hath made all men free and equal” (Productions 5). She demands both religious piety and solidarity: “Never, no, never will the chains of slavery and ignorance burst, till we become united as one, and cultivate among ourselves the pure principles of piety, morality and virtue” (6). Furthermore, she directly addresses Black women, insisting that they will not be able to rise up until they “begin to promote and patronize each other” (16), and exhorting them to fulfill their potential:

O, ye daughters of Africa, awake! awake! arise! no longer sleep nor slumber, but distinguish yourselves. Show forth to the world that ye are endowed with noble and exalted faculties. O, ye daughters of Africa! what have ye done to immortalize your names beyond the grave? What examples have ye set before the rising generation? What foundation have ye laid for generation yet unborn? (6)

She speaks to the responsibility that rests on mothers, who “must create in the minds of your little girls and boys a thirst for knowledge, the love of virtue, the abhorrence of vice, and the cultivation of a pure heart” (13). She urges women to raise funds such that, “at the end of the one year and a half, we might be able to lay the corner-stone for the building of a High School” (16). And, through an understanding of the oppression caused by the intersection of race, gender and class, she asks why Black women should always be doing the drudge work for others: “How long shall the fair daughters of Africa be compelled to bury their minds and talents beneath a load of iron pots and kettles?” (16). In a remarkable passage, she presses Black women to be more like (white) American men, to rise above menial labour, to fight for their rights and “get what we can”:

Do you ask the disposition I would have you possess? Possess the spirit of independence. The Americans do, and why should not you? Possess the spirit of men, bold and enterprising, fearless and undaunted. Sue for your rights and privileges. Know the reason that you can attain them. Weary them with your importunities. You can but die, if you make the attempt; and we shall certainly die if you do not. The Americans have practiced nothing but head-work these 200 years, and we have done their drudgery. And is it not high time for us to imitate their examples, and practise head-work too, and keep what we have got, and get what we can? We need never to think that any body is going to feel interested for us, if we do not feel interested for ourselves. (17)

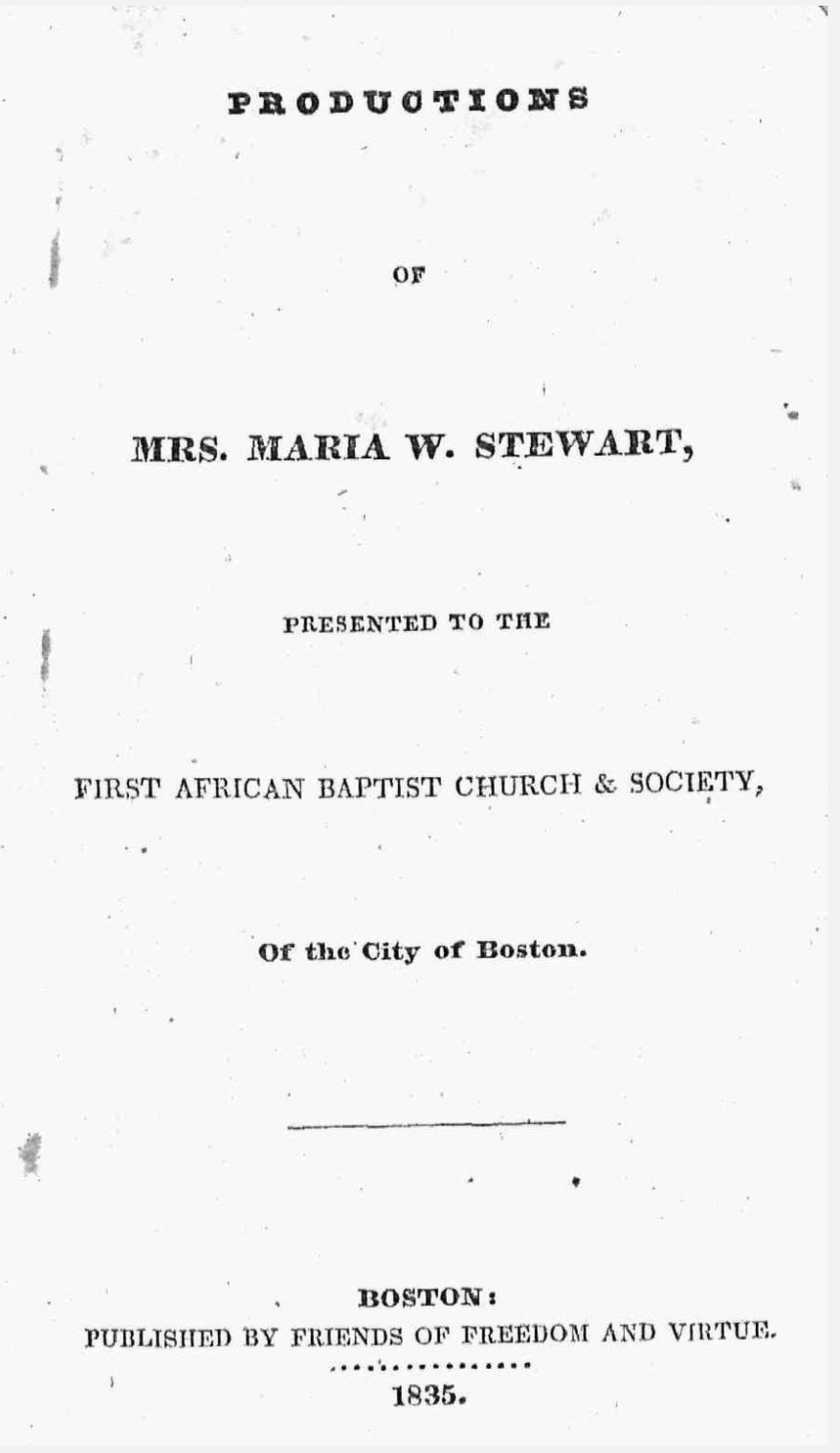

Stewart’s decision to speak publicly, through print and then through lectures, was motivated by the earlier publication of David Walker’s Appeal, on 28 September 1829. David Walker, a free man of a free-born woman and an enslaved man, used his manifesto to describe the terrible suffering inflicted by slavery and racism against freed and enslaved Blacks, to challenge white supremacy (including a refutation of Thomas Jefferson’s published assertions of Black inferiority), and to repudiate plans to forcibly deport free Blacks to African colonies. Most significantly, he called upon Black men and women to actively take part in their liberation from slavery and fight for equal rights. These views were deemed too radical by most white abolitionists, and Southern whites took extreme measures to prevent the distribution of the pamphlet in the South, including labelling the Appeal seditious and harshly penalizing anyone found circulating it; the state of Georgia even laid a bounty on Walker’s head, $10,000 if delivered alive, $1,000 if dead (Zinn 180). Walker’s death, in the summer of 1830, was further inspiration for Stewart to take up the cause of the “most noble, fearless, and undaunted David Walker” (Productions 5). Stewart did so by adapting Walker’s Appeal, in speaking on numerous occasions directly to Black women, and by extending Walker’s arguments in demanding that Blacks actively seek out both emancipation and religious, education and moral improvement.

Figure 2. Walker’s Appeal, in Four Articles, 3rd ed. DocSouth.

In a letter, William Lloyd Garrison describes his first meeting with Stewart shortly after Walker’s death, and how her first pamphlet, Religion and the Pure Principles of Morality, came to be published in 1831:

Soon after I started the publication of The Liberator you made yourself known to me by coming into my office and putting into my hands, for criticism and friendly advice, a manuscript embodying your devotional thoughts and aspirations, and also various essays pertaining to the condition of that class with which you were complexionally identified – a class “peeled, meeted out, and trodden under foot.” You will recollect, if not the surprise, at least the satisfaction I expressed on examining what you had written – far more remarkable in those early days than it would be now, when there are so many educated persons of color who are able to write with ability. I not only gave you words of encouragement, but in my printing office put your manuscript into type, an edition of which was struck off, in tract form, subject to your order. (Stewart, Meditations 6)

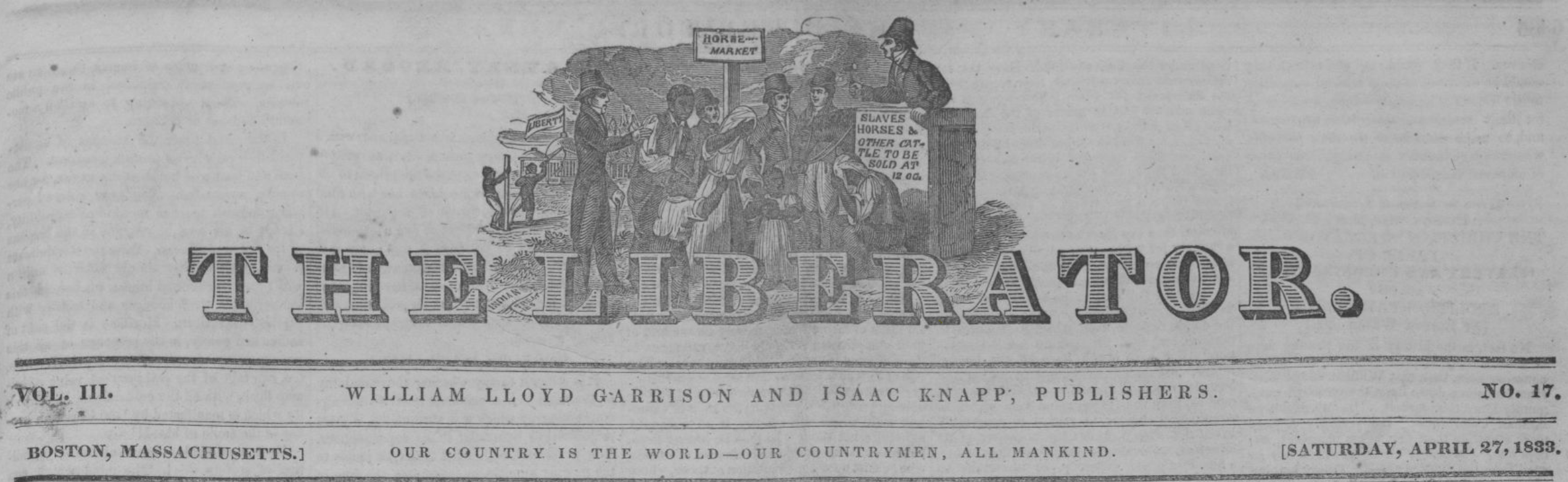

Figure 3. The Liberator masthead, vol. 3, no. 17, 27 Apr. 1833. American Historical Periodicals from the American Antiquarian Society

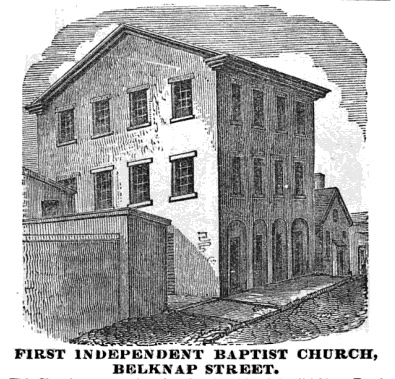

Print was not the only way that Stewart sought to reach an audience. Meditations from the Pen of Mrs. Maria W. Stewart: presented to the First African Baptist Church and Society, in the city of Boston (1832), a 28-page pamphlet, includes a series of short meditations and prayers that she may have delivered orally at her church. Built in 1806, the First African Baptist Church is the oldest extant African American Church. It is the site of the first meeting of the New England Anti-Slavery Society (on 1 January 1831), and also where Stewart gave her farewell address (the last of her four known lectures) on 21 September 1833. Stewart’s meditations specifically address an African American audience, with prayers “for the whole race of mankind; especially for the benighted sons and daughters of Africa. Do thou loose their bonds, and let the oppressed go free” (Productions 37).

Figures 4 and 5. First Independent Baptist Church, Belknap St., Boston, from Isaac Smith Homans' Sketches of Boston, Past and Present. Wikipedia (left); African Meeting House, Wikipedia (right).

Between September 1832 and September 1833, Stewart delivered four lectures at various venues in Boston, where she addressed male, female and mixed-gender and -race audiences. Accounts of three of these speeches were first published by William Lloyd Garrison in the pages of his Liberator, then collected and printed by Garrison and Isaac Knapp in the 1835 collection, Productions of Mrs. Maria W. Stewart: presented to the First African Baptist Church & Society of the city of Boston. The following table provides information about her lectures and their publication history. Her lectures were usually reprinted in The Liberator a few months after they were delivered. Marilyn Richardson has also found one further essay by Stewart, “Causes for Encouragement,” published in The Liberator on 14 July 1832 (110).

Table 1.

| Date / Title |

Venue |

Audience |

The Liberator |

Productions |

|

September 21, 1832

|

Franklin Hall, Boston |

New England Anti-Slavery Society |

17 November 1832, p. 183 |

52–56 |

|

No date, probably spring 1832 |

Boston |

Afric-American Female Intelligence Society |

28 April 1832, p. 66-67 |

57–63 |

|

February 27, 1833 |

African Masonic Hall, Boston |

African American Masons |

27 Apr. 1833, p. 68 and 4 May 1833, p. 72 |

64–72 |

|

September 21, 1833 |

First African Baptist Church, Boston |

Friends in the City of Boston |

This lecture was not printed in The Liberator. |

73–84 |

In her lectures, Stewart continued in the same fiery vein as Religion and the Pure Principles of Morality, though, perhaps because her lectures were delivered in person, they were highly controversial; the negative reaction to them resulted in her ending her speaking career after only four engagements, all of which occurred within one year (Hine; Roberts). It is highly unusual to have a record of a woman’s lectures; in the whole of our thousands of title records in the WPHP, the only records described as oral accounts are the final confessions of condemned women (for example, “The last speech, confession and dying words, of Mary Sanders” and “The last dying speech, of Miss Mary Laws”). We are also fortunate that Stewart’s speeches were reprinted from The Liberator, as the WPHP’s data model can only record periodicals published as annuals. As a result of the uniqueness of Stewart’s publications, this spotlight takes the opportunity to quote from her lectures, at length, as they provide direct access to a woman’s speaking voice, rarely afforded in a work written for print. Marilyn Richardson has called to our attention the distinctive patterns and power of Stewart's voice:

As with Walker, much of the force of Stewart's message was borne by a rhetorical power that appealed to the ear as well as to the intellect. Not only did she master the Afro-American idiom of thundering exhortation uniting spiritual and secular concerns, she was able early on to exercise that skill with equal success on the printed page and at the podium. Her command of such sophisticated techniques as the implied call-and-response cadence set in motion by sequential rhetorical questions; of anaphora, parataxis, and the shaping of imperative and periodic sentences; along with the powerful and affecting rhythms of her discourse, all show Stewart to be a predecessor to Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglass, Henry Highland Garnet, Frances Harper, and other black nineteenth-century masters of language deployed to change society. (30)

Stewart’s lectures continue to speak to us today.

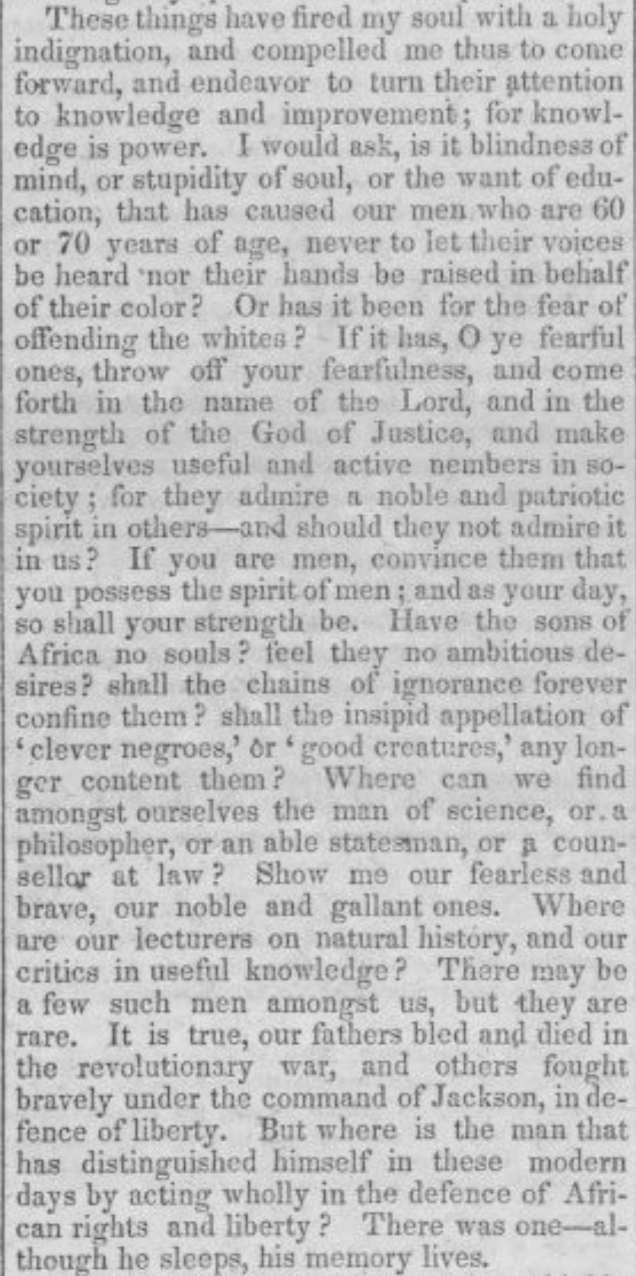

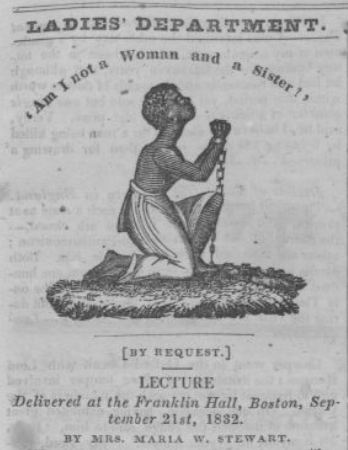

Figure 6. “Lecture Delivered at the Franklin Hall, Boston, September 21st, 1832.” The Liberator, vol. 2, no. 46, 17 Nov. 1832. American Historical Periodicals from the American Antiquarian Society

In her first speech to the New England Anti-Slavery Society, on 12 September 1832, Stewart echoes her previous complaints about the stultifying effects of “a life of servitude,” declaring “that if I conceived of there being no possibility of my rising above the condition of a servant, I would gladly hail death as a welcome messenger” (Productions 53). In addressing the Afric-American Female Intelligence Society, she again calls for solidarity: “It appears to me that there are no people under the heavens, so unkind and so unfeeling towards their own, as are the descendants of fallen Africa. I have been something of a traveller in my day; and the general cry among the people is, ‘Our own color are our greatest opposers;’ and even the whites say that we are greater enemies towards each other, than they are towards us” (Productions 60). Her third speech, however, was the most controversial. Delivered at the African Masonic Hall, in an address exclusively directed to men, she calls upon them to rise beyond ignorance and fear (implying that they had been weak by not doing so). This is how one part of her speech appeared in The Liberator for 27 April 1833:

Figure 7. “An Address, Delivered at the African Masonic Hall in Boston, Feb. 27, 1833.” The Liberator, vol. 3, no. 17, 27 Apr. 1833, American Historical Periodicals from the American Antiquarian Society

It was this speech that turned the tide against her; her next and final public lecture was the “Farewell Address to her Friends in the City of Boston,” wherein she alludes to the biting criticism that had been directed at her. This final speech is remarkable as it offers a wide-ranging account of the high status of many women throughout history. Here is her discussion of women in the late middle ages, drawn, according to Richardson (40), from Stewart's reading of John Adams' Woman, Sketches Of The History, Genius, Disposition, Accomplishments, Employments, Customs And Importance Of The Fair Sex In All Parts Of The World (London, 1790):

In the 15th century, the general spirit of this period is worthy of observation. We might then have seen women preaching and mixing themselves in controversies. Women occupying the chairs of Philosophy and Justice; women harangueing in Latin before the Pope; women writing in Greek, and studying in Hebrew; Nuns were Poetesses, and women of quality Divines; and young girls who had studied Eloquence, would with the sweetest countenances, and the most plaintive voices, pathetically exhort the Pope and the Christian Princes, to declare war against the Turks. Women in those days devoted their leisure hours to contemplation and study. The religious spirit which has animated women in all ages, showed itself at this time. It has made them, by turns, martyrs, apostles, warriors, and concluded in making them divines and scholars. Why cannot a religious spirit animate us now? Why cannot we become divines and scholars? (Productions 77)

This published lecture, in which she pleads for a place for women in public debate and religious life by referencing the powerful influence of women throughout history, would be her last. In 1834, Stewart moved to New York City, then Baltimore and finally to Washington, DC, where she worked as a teacher and then as head matron at the Freedmen’s Hospital, where she taught and treated formerly enslaved people. Through education, nursing and other forms of activism she continued to fight for the liberty of her people. She died in 1879, the year in which she collected and published her writing as Meditations from the Pen of Mrs. Maria W. Stewart, with additional reminiscences supplied by others who knew her. In her 1987 edition of Stewart’s writing, the first republication of her work since 1897, Marilyn Richardson observes that Stewart is “a significant historical figure, hidden in plain sight” (xv); with the recovery work of Richardson and other scholars, her important legacy is finally coming into view.

WPHP Records Referenced

Stewart, Maria W. (person, author)

Religion and the Pure Principles of Morality, the Sure Foundation on Which We Must Build (title)

Garrison, William Lloyd, and Isaac Knapp (firm, publisher, and printer)

"The last speech, confession and dying words, of Mary Sanders" (title)

"The last dying speech, of Miss Mary Laws" (title)

Works Cited

Hine, Darlene Clark. Black Women in America. 2nd ed., Oxford UP, 2005.

Richardson, Marilyn, ed. Maria W. Stewart, America’s First Black Woman Political Writer: Essays and Speeches. Indiana UP, 1987.

Richardson, Marilyn, ed. "Stewart, Maria W." The Concise Oxford Companion to African American Literature, Oxford UP, 2002.

Roberts, Rita. "Stewart, Maria W. (1803-1879), writer, black activist, and teacher." American National Biography, Oxford UP, 2000. https://doi.org/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1500942.

Stewart, Maria W. Meditations from the Pen of Mrs. Maria W. Stewart, (Widow of the Late James W. Stewart,) Now Matron of the Freedman’s Hospital, and Presented in 1832 to the First African Baptist Church and Society of Boston, Mass. Enterprise Publishing Company, 1879.

Stewart, Maria W. Productions of Mrs. Maria W. Stewart, Presented to the First African Baptist Church & Society of the City of Boston. Boston, Friends of Freedom and Virtue, 1835. Digital Schomburg African American Women Writers of the 19th Century. http://digilib.nypl.org/dynaweb/digs/wwm9722/@Generic__BookView.

Zinn, Howard. A People's History of the American States: 1492 to the Present. Harper Collins, 2003.

Further Reading

Collins, Patricia Hill. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. 2nd ed., Routledge, 2000.

Stewart, Maria W. “An Address, Delivered at the African Masonic Hall in Boston, Feb. 27, 1833.” The Liberator, vol. 3, no. 17, 27 Apr. 1833, p. 68.

Stewart, Maria W. “An Address, Delivered at the African Masonic Hall in Boston, Feb. 27, 1833 (Concluded).” The Liberator, vol. 3, no. 18, 04 May 1833, p. 72.

Stewart, Maria W. “An Address Delivered Before the Afric-American Female Intelligence Society of Boston.” The Liberator, vol. 2, no. 17, 28 Apr. 1832, pp. 66-67.

Stewart, Maria W. “Causes for Encouragement.” The Liberator, vol. 2, no. 28, 14 July 1832, p. 110.

Stewart, Maria W. “Lecture Delivered at the Franklin Hall, Boston, September 21st, 1832.” The Liberator, vol. 2, no. 46, 17 Nov. 1832, p. 183.