This post is part of our Spooky Spotlight Series, which will run through October 2020. Spotlights in this series focus on Gothic titles, authors, and firms in the database.

Authored By: Victoria DeHart

Edited By: Michelle Levy, Kandice Sharren, and Amanda Law

Submitted on: 10/02/2020

Citation: DeHart Victoria. "The Enchanting Ann Radcliffe." The Women's Print History Project, 2 Oct 2020, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/37.

Figure 1. Portrait of Ann Radcliffe. Courtesy of the Women’s Museum of California.

Ann Radcliffe was a pioneer of the gothic literary genre. Her inspirations were The Castle of Otranto (1764) by Horace Walpole, often named the first gothic novel; The Old English Baron (1777) by Clara Reeve, and The Recess; Or, a Tale of Other Times (1783–1785) by Sophia Lee (Miles, 2004 4). By the time she published her successful novel, The Romance of the Forest in 1791, gothic fiction was considered “the trash of the circulating libraries” and a “cheap and tawdry form of entertainment” (Townshend 2014). However, Radcliffe was considered to be an exception, she was lauded by her contemporaries as “the Shakespeare of Romance writers” and as “a genius of no common stamp” (Miles, 1995 7; Barbauld, 1810 i). Radcliffe single-handedly changed the gothic novel; it was by her inclusion of original poetry as part of her novels and as epigraphs, as well as her elaborate descriptions of landscapes, that she elevated the form. Critics agreed that Radcliffe had moulded pre-existing literary components to refine a “new, powerful, and enchanting” genre of literature (Miles, 2004 4).

Born Ann Ward (1764–1823), she was the only child of Ann Oats (1726–1800) and William Ward (1737–1798), a haberdasher (Miles, 2004 1). After the collapse of his haberdashery business, William Ward moved the family to Bath, to work for his brother-in-law, Thomas Bentley (1731–1780), a crucial figure in Ann Ward’s early life (Miles 2004 1). Through Bentley, Ward was introduced to the writers Elizabeth Montagu (1718–1800), and Hester Piozzi (1741–1821), and she became close to Susannah Wedgwood, the daughter-in-law of Erasmus Darwin (1731–1802) (Miles, 2004 1–2). In 1787, she married William Radcliffe (1763–1830), an Oxford law graduate and an editor and reporter for The English Chronicle (Miles, 2004 1).

Figure 2. Title page of The Romance of the Forest, 1825 edition. The British Museum.

Ann Radcliffe published her first romance, The Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne, in 1789 and her second novel, A Sicilian Romance, the following year. Reviews for the novels were positive, but critics were largely indifferent to her work (Miles, 1995 22). It was The Romance of the Forest, published in 1791, that catapulted Radcliffe to fame (Miles, 2004 2). The spectacular success of The Romance of the Forest is evident by the fact that six editions were published within four years; four in London (1791, 1792, 1792, 1794), and two in Dublin (1792, 1793).

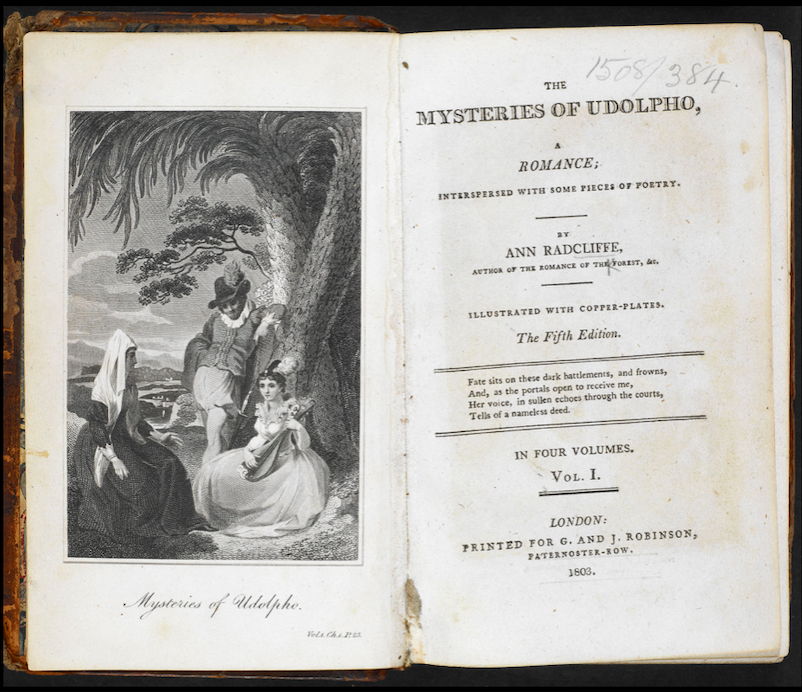

The publication of The Mysteries of Udolpho, in 1794, brought Ann Radcliffe further recognition in both Britain and Europe and became her most popular novel (Miles, 1995 24). Within a decade, five London editions (1794; 1794; 1795; 1799; 1803) were in circulation, and three in Ireland (1794; 1795; 1800). In an age when many novels were printed only once and largely read through loans from circulating libraries, where a single copy could be reread multiple times, this degree of reprinting is remarkable. After Udolpho, the literary world overflowed with gothic literature. Robert Miles (2004) estimates that a third of all new novels published after 1794 were gothic fiction (4). Michael Gamer agrees that the 1790s saw many writers adopt Radcliffe’s “explained supernatural” approach, with the majority of them appearing nine months after Udolpho was published (72). Many women in the database are considered imitators of Radcliffe, particularly Isabella Kelly, Eliza Parsons, and Catherine Cuthbertson, and they began to publish their gothic novels in 1794 (Nowak 4; Gamer 72; Norton, 2000 88).

Figure 3. The Mysteries of Udolpho, Illustrated with Copper Plates. Fifth edition, Courtesy of the British Library

In 1795 she published A Journey Made in the Summer of 1794, detailing her trips through Holland and Germany and the English Lake District. The travelogue was well received and reprinted in London and Ireland in the same year. Townshend and Wright argue that A Journey “confirmed [Radcliffe’s] reputation as a writer of considerable versatility, as adept at the crafting of travel journalism as she was at poetry and romance” (9).

In addition to being critically successful and popular, Radcliffe was England’s highest paid novelist during the 1790s. She earned £500 for Udolpho (1794) and for her final novel, the Italian (1797), she earned £800 (Miles, 2004 4). According to Robert Miles (2004), Radcliffe’s “nearest competitor” before 1797, was the playwright and novelist Frances Burney, who received £250 for Cecilia, Memoirs of an Heiress in 1782 (4).

The Italian, Or the Confessional of the Black Penitents (1797) was the last of her novels published during her lifetime; a surprise to many, given her record of success. During her eight year career, Radcliffe was admired for her use of both epigraphs and poetry within her novels. The only other book published before her death in 1823 was a single work of poetry, The Poems by Mrs. Radcliffe published in 1815, although it may have been published without Radcliffe’s consent (Townshend and Wright 13). The book contained no new material and instead featured poetry excerpted from her novels: Athlin and Dunbayne, A Sicilian Romance, The Romance of the Forest, and Udolpho; the book was well received and republished the following year (Townshend and Wright 13).

Figure 4. Pastoral Landscape: The Roman Campagna, by Claude Lorrain, courtesy of the MET. Radcliffe’s descriptions of landscapes were inspired by the paintings of Claude Lorrain and Salvator Rosa (Talfourd 65).

Dale Townshend and Angela Wright refer to Radcliffe’s disappearance after the publishing of the Italian as the “Radcliffean Interregnum” (13). Although no new novels were published during the interregnum, new editions of her novels circulated. In 1799, the third, fourth, and sixth editions, of The Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne, The Mysteries of Udolpho, and The Romance of the Forest, were printed respectively. Until the middle of the nineteenth century, Radcliffe’s popularity continued; nearly every year at least one of her novels was reprinted. The latest reprint we have in the database is the 1834 edition of Udolpho published in Exeter.

The literary world could not comprehend that the highest paid and most popular novelist of the 1790s had stopped publishing new material. In 1800, rumours began to circulate that Ann Radcliffe had died; and by 1811, false reports stated that she was restrained within Haddon Hall in Derbyshire, driven “mad” by the “morbid exuberance of her [own] imagination” (Smith 155; Miles, 1995 25). There is no clear reason for Radcliffe’s disappearance, but scholars have offered different ideas; Townshend and Wright (2014) believe her interregnum may have been due to a combination of her frustration with the plethora of “Radcliffe imitators” in the market, and the mixed reviews she received for The Italian (13). Ann Radcliffe was also plagued with poor health in the last twelve years of her life (Norton, 1999 236).

Authors and firms tried to capitalise on her disappearance and her name was “unwarrantably employed” (Norton, 1999 214). Several novels in the database are printed with the name “Radcliffe'' on their title pages, or some other version, such as Radclife or Ratcliffe (Norton, 1999 214). For example, we have collected the works of Mary Ann Radcliffe, an early feminist writer and the suppositious novelist of Manfrone; or, The One-Handed Monk (1809). The novels written by Mary Ann Radcliffe often have her name printed; according to her memoirs (1810), she was pressured by her publisher to use her name in the hope of benefitting from the similarities to Ann Radcliffe (M.A., Radcliffe 387).

Although Ann Radcliffe stopped publishing after 1797, she continued to write (Miles 2004 5). In A Memoir of the Author, with Extracts from her Journal (1826) written by Thomas Noon Talfourd, it is revealed that Radcliffe was a meticulous travel writer, detailing her yearly trips to the southern coast of England accompanied by her husband (Talfourd 15). After her death in 1823, several posthumous works were published by William Radcliffe; a final novel, Gaston de Blondeville (1826); St Alban’s Abbey (1826), a poem found within Gaston de Blondeville; and an unfinished essay, On the Supernatural in Poetry (1826) (Miles, 2004 5). Gaston de Blondeville was warmly received, particularly because of its descriptions of the English landscape (Townshend and Wright 27).

Evident in the countless editions of her novels, Ann Radcliffe was both a critical and financial success. She was instrumental in refining the gothic novel and she inspired countless authors of the eighteen and nineteenth centuries. Because of her influence and enduring popularity, we have chosen Ann Radcliffe to launch our Spotlight series on gothic literature.

WPHP Records Referenced

Radcliffe, Ann (person, author)

The Old English Baron (title)

Reeve, Clara (person, author)

The Recess; Or, a Tale of Other Times (title)

Lee, Sophia (person, author)

Montagu, Elizabeth (person, author)

Piozzi, Hester (person, author)

Darwin, Erasmus (person, author)

Radcliffe, William (person, author)

The Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne (title)

A Sicilian Romance (title)

The Romance of the Forest (title)

The Romance of the Forest (title, second edition)

The Romance of the Forest (title, third edition)

The Romance of the Forest (title, fourth edition)

The Romance of the Forest (title, first Irish edition)

The Romance of the Forest (title, second Irish edition)

The Mysteries of Udolpho (title)

The Mysteries of Udolpho (title, second edition)

The Mysteries of Udolpho (title, third edition)

The Mysteries of Udolpho (title, fourth edition)

The Mysteries of Udolpho (title, fifth edition)

The Mysteries of Udolpho (title, first Irish edition)

The Mysteries of Udolpho (title, second Irish edition)

The Mysteries of Udolpho (title, third Irish edition)

Kelly, Isabella (person, author)

Parsons, Eliza (person, author)

Cuthbertson, Catherine (person, author)

A Journey Made in the Summer of 1794 (title)

A Journey Made in the Summer of 1794 (title, second edition)

A Journey Made in the Summer of 1794 (title, first Irish edition)

The Italian, Or the Confessional of the Black Penitents (title)

The Poems by Mrs. Radcliffe (title)

The Poems by Mrs. Radcliffe (title, second edition)

The Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne (title, third edition)

The Romance of the Forest (title, sixth edition)

The Mysteries of Udolpho (title, 1834 edition)

Radcliffe, Mary Ann (person, author)

Manfrone; or, The One-Handed Monk (title)

The Memoirs of Mrs. Mary Ann Radcliffe: in Familiar Letters to Her Female Friend (title)

Talfourd, Thomas Noon (person, introducer)

Gaston de Blondeville (title)

Works Cited

Barbauld, Anna Laetitia. The British Novelists; with an Essay; and Prefaces, Biographical and Critical, By Mrs. Barbauld, Vol. 43. F.C. and J. Rivington, et al., 1810.

Gamer, Michael. Romanticism and the Gothic: Genre, Reception, and Canon Formation. Cambridge UP, 2000.

Miles, Robert. “Radcliffe [nee Ward], Ann (1764–1823). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/22974

Miles, Robert. Ann Radcliffe: The Great Enchantress. Manchester UP, 1995.

Norton, Rictor. Mistress of Udolpho: The Life of Ann Radcliffe. Leicester UP, 1999.

Norton, Rictor. Gothic Readings: The First Wave, 1764-1840. Leicester UP, 2000.

Nowak, Tenille. “Isabella Kelly’s Twist on the Standard Racliffean Romance.” Studies in Gothic Fiction, vol 1, no. 2, 2012, pp. 4–13.

Radcliffe, Mary Ann. The Memoirs of Mrs. Mary Ann Radcliffe: in Familiar Letters to Her Female Friend. Printed for the Author, 1810.

Smith, Orianne. Romantic Women Writers, Revolution, and Prophecy: Rebellious Daughters, 1786-1826. Cambridge UP, 2013.

Talfourd, Thomas Noon. “Memoir of the life and writings of Mrs. Radcliffe.” In Ann Radcliffe, Gaston de Blondeville, vol.1, pp. 1–132, 1826.

Townshend, Dale. “An Introduction to Ann Radcliffe.” British Library, 2014. https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/an-introduction-to-ann-radcliffe.

Townshend, Dale, and Angela Wright. “Gothic and Romantic Engagements, The Critical reception of Ann Radcliffe, 1789–1850.” Ann Radcliffe, Romanticism and the Gothic, edited by Dale Townshend and Angela Wright, Cambridge UP, 2014, pp. 3–32.

Further Reading

Baker, Samuel. "Ann Radcliffe beyond the Grave." Ann Radcliffe, Romanticism and the Gothic, edited by Dale Townshend and Angela Wright, Cambridge UP, 2014, pp. 168–82.

Norton, Rictor. "Ann Radcliffe, ‘The Shakespeare of Romance Writers.” Shakespearean Gothic, 2019, pp. 33–59.

Schmidt, Michael. “The Eerie: Horace Walpole, Clara Reeve, William Beckford, Ann Radcliffe, Mathew Gregory Lewis, Charles Brockden Brown, Charles Robert Maturin." In The Novel: A Biography, Harvard UP, 2014, pp. 162–76.