This post is part of our Spooky Spotlight Series, which will run through October 2020. Spotlights in this series focus on Gothic titles, authors, and firms in the database.

Authored by: Michelle Levy

Edited by: Kandice Sharren and Victoria DeHart

Submitted on: 10/30/2020

Citation: Levy, Michelle. "Mary Wollstonecraft and the Domestic Gothic Novel." The Women's Print History Project, 30 Oct 2020, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/49.

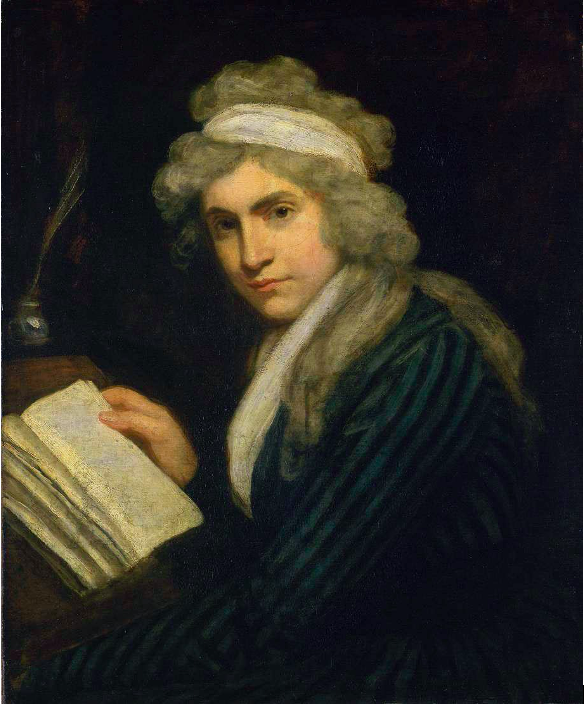

Figure 1. The first page of Maria, or the Wrongs of Woman. Wikipedia.

ABODES of horror have frequently been described, and castles, filled with spectres and chimeras, conjured up by the magic spell of genius to harrow the soul, and absorb the wondering mind. But, formed of such stuff as dreams are made of, what were they to the mansion of despair, in one corner of which Maria sat, endeavouring to recal her scattered thoughts!

So begins Mary Wollstonecraft’s novel. In these opening lines, Wollstonecraft invokes some of the recurring features, the castles and spectres, of the gothic novels that flooded the literary marketplace in the 1790s. But she raises the tropes of the gothic to make a bold and shocking claim that the real horrors were those facing middle- and working-class British women, not the imagined threats to heroines of novels living in times past, in foreign lands. As Michael Gamer notes: “Novels set in thirteenth-century Italy, sixteenth-century Spain, or seventeenth-century France could traffic in attempted rape, forced marriage, or abduction and confinement, thrilling English readers while assuring them of their comparative liberty, safety and enlightenment,” but Wollstonecraft’s novel “give[s] the lie to such comforting assertions” (295–96).

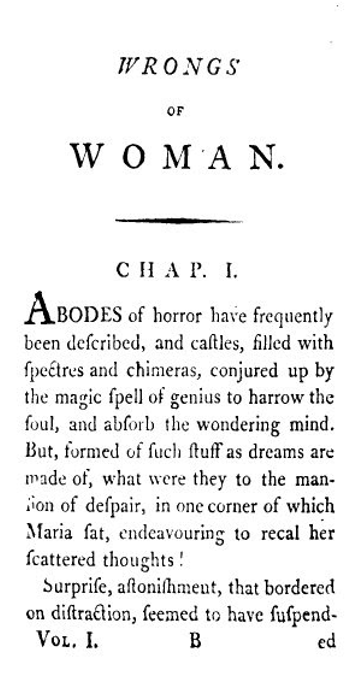

Figure 2. Mary Wollstonecraft (Mrs William Godwin) by John Opie (c. 1790-1). Photo © Tate, CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0. Unported.

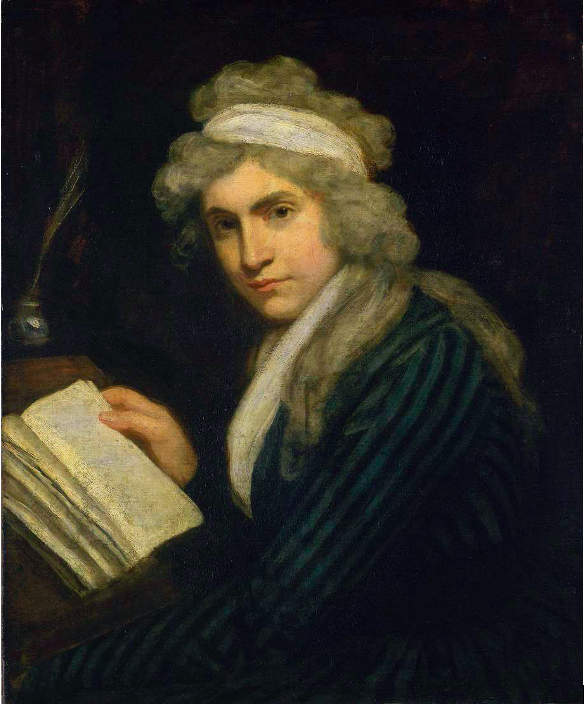

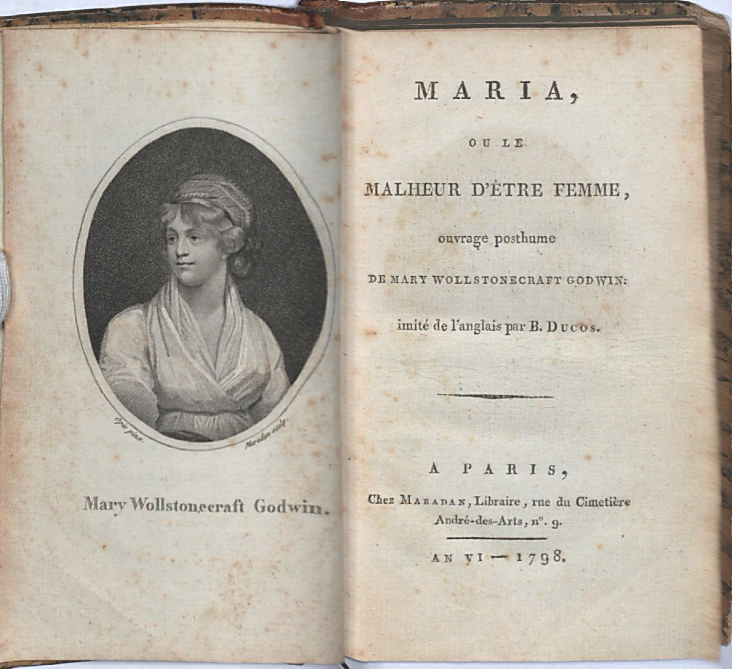

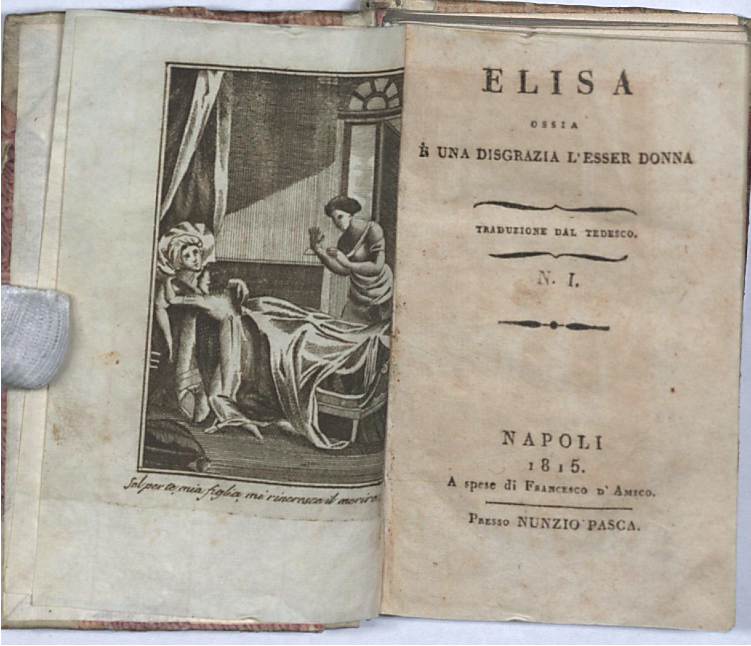

The Wrongs of Woman, or Maria. A Fragment, was published just months after Wollstonecraft died, on 10 September 1797, at the age of 37, from complications from childbirth—her daughter Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, was born 11 days before. Wollstonecraft’s husband, the political thinker and novelist William Godwin, published this unfinished novel in a four-volume compilation of Wollstonecraft’s unpublished writing, under the title Posthumous Works of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Women, in January 1798. It was reprinted the same year in Dublin. Even though, as discussed below, the novel's reception suffered from the damage done to Wollstonecraft’s reputation by the simultaneous publication of the Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, Maria was nevertheless extracted from the four volume collection and republished globally: in Paris in a French translation, in 1798; in Philadelphia, in 1799; in Leipzig, in a German translation, in 1800; and in Naples, in an Italian translation, in 1815.

Figure 3. The French translation of Maria, published in Paris in 1798. Princeton University.

Throughout the novel, Wollstonecraft demonstrates in painstaking and painful detail the real terrors facing living and breathing English women. The ‘mansion of despair’ that Maria sits in is both the prison of her mind after extended and extensive abuse, and the actual insane asylum in which she has been legally though unjustly incarcerated by her husband. The list of ‘wrongs’ that women suffer is lengthy. Chapters seven through fourteen (about half of the completed manuscript) are Maria’s first-person account of events leading up to her imprisonment. We learn how her parents favoured their eldest son, who ruled ‘despotically’ over the siblings and how, to escape her home, she married George Venables, about whom she knew little and from whom her family failed to protect her. Indeed, Venables only agrees to marry Maria because of her uncle’s gift of £5,000, which is transacted between the men without Maria’s knowledge. Upon their marriage, her husband’s true character is quickly revealed, as he quickly shows himself to be a libertine, gambler, and alcoholic who drives the family to bankruptcy, forcing Maria to give him any additional money she manages to secure from her uncle. During Maria’s pregnancy, Venables attempts to sell her to another man as a means of raising more money. After this final outrage, Maria leaves him, only to be advertised for in the newspapers as a runaway, to be turned out of lodgings for leaving her husband, and to be “hunted like a criminal from place to place” (1798, II: 149). When Venables finally tracks her down, he abducts her and shuts her in an asylum, wrenching her infant daughter away from her. When, after her escape from the asylum, she seeks a divorce, she is mocked and humiliated by the judge. Thus Maria concludes that “a wife being as much a man’s property as his horse, or his ass, she has nothing she can call her own” (1798, II: 45-46)—not her child, not even her own body.

Figure 4. The German translation of Maria, published in Leipzig in 1800, from the French translation. Copyright © 2020 Simon Beattie.

Through this narrative, Wollstonecraft documents the legal and socially sanctioned persecution of women. As a child, Maria saw how her family’s resources (including love) were devoted entirely to her eldest brother, replicating the system of primogeniture by which estates were passed entire to the male heir, leaving nothing or little in most families to female siblings (and younger sons). As a young woman, an inadequate education—what Wollstonecraft called a “false system of education” (A Vindication of the Rights of Women, 1798: 2)—ill-prepares her to make a worthy choice of a mate. As a married woman, she enjoys no right to her dowry, reflecting the common law principle of coverture, by which women’s property were passed to her husband. She has few rights to her body or to her infant daughter, mirroring the legal status of women upon marriage. As William Blackstone explains in his Commentaries on the Laws of England, property becomes a man’s upon marriage:

This depends entirely on the notion of an unity of person of husband and wife; it being held that they are one person in law, so that the very being and existence of the women is suspended during the coverture, or entirely merged or incorporated in that of the husband. And hence it follows, that whatever personal property belonged to the wife, before marriage, is by marriage absolutely vested in the husband. (II:433)

When Maria asserts that “marriage had bastilled me for life” (1798, II:34) she recognizes not only that marriage is a prison, but that it is a political prison; that the norms and laws that govern her unjust treatment are man-made.

In chapter 5, Jemima, a working-class woman who works as a guard at the asylum, tells a different but equally harrowing account of her life. She explains how she was doomed to repeat her mother’s victimization: her mother was a servant who was raped by her employer and then forced to leave to give birth to Jemima, and Jemima herself is raped and impregnated by the man who has apprenticed her, who forces her from the house. Jemima survives only by self-administering a dangerous abortion. Her only option is then to turn to sex work. As a result, her control over her body is constantly threatened, for example, by the watchmen who demand payment for allowing her to work the streets. She must be ruthless to save herself. When Jemima hears the story of Maria’s wrongful imprisonment, however, she relents in her willingness to act as Maria’s jailor and helps her escape.

Figure 5. The Italian translation of Maria, published in Naples in 1815. Princeton University.

Figure 5. The Italian translation of Maria, published in Naples in 1815. Princeton University.

Another important but under-developed character is Darnford, a prisoner at the same asylum, who Maria meets and falls in love with; he becomes a romantic interest and her possible saviour. However, doubts about his motivations and character surface, and raise the spectre of another threat to Maria, that her own desire for affection and intimacy might endanger her freedom once again. There is no resolution to the question of Darnford’s intentions, nor indeed on any other matter, such as whether Maria is reunited with her daughter, or whether Maria and Jemima join together to rescue each other. Godwin published the novel with a few possible endings, taken from manuscript notes Wollstonecraft left behind. But the possibility that Maria’s heart deceives her, and that sexual love itself is a trap for women, is perhaps the darkest of all elements in this deeply gothic yet highly realistic, domestic novel.

It is fitting, I believe, to end our spotlight series on the gothic with Mary Wollstonecraft’s incomplete novel, as The Wrongs of Woman itself, as well as the circumstances and outcomes of its publication, reveal the stakes for women, and for women writers, at this time. The novel itself presents the ‘abodes of horror’ that everyday women in England inhabited, fulfilling the ambitions Wollstonecraft outlined in the preface “of exhibiting the misery and oppression, peculiar to women, that arise out of the partial laws and customs of society” (1798, “Author’s Preface,” I:np). The novel was unfinished (and published as “A Fragment”) because of Wollstonecraft’s untimely death due to routine complications following childbirth. Godwin’s Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, published in the same year as Posthumous Works, included overly frank revelations about Wollstonecraft’s love affairs, pregnancies and suicide attempts, which not only compromised the reception of the novel but destroyed her personal reputation (McDayter). In fact, reviewers used the Memoirs’ revelations to conflate Wollstonecraft with Maria, with many condemning the novel’s heroine as they did Wollstonecraft herself, and in so doing failing to appreciate the novel’s critical representation of the heroine. The infant girl Wollstonecraft gave birth to in 1798 would be haunted by the absence of her mother, and would become a writer herself, at the age of 18 penning Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus, a transformation of the gothic into one the most disturbing and enduring novels ever written.

WPHP Records Referenced

Wollstonecraft, Mary (person, author)

Godwin, Mary Wollstonecraft (person, author)

Godwin, Wiliam (person, author)

Posthumous Works of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Women (title)

Memoirs and Posthumous Works of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Women (title, first Irish edition)

Maria, ou, Le malheur d'être femme; ouvrage posthume de Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, imité de l'anglais par B. Ducos (title, first French edition)

Maria, or The Wrongs of Woman (title, first American edition)

A Vindication of the Rights of Women (title)

Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus (title)

Works Cited

Blackstone, William. Commentaries on the laws of England. Clarendon, 1765.

Botting, Eileen Hunt. “Nineteenth-Century Critical Reception.” Mary Wollstonecraft in Context, edited by Nancy E. Johnson and Paul Keen, Cambridge UP, 2020, pp. 50–56.

Flanders, Judith. “Prostitution.” British Library, 2014.<https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/prostitution.

Gamer, Michael. “The Gothic.” Mary Wollstonecraft in Context, edited by Nancy E. Johnson and Paul Keen, Cambridge UP, 2020, pp. 289–96.

McDayter, Ghislaine. “On the Publication of William Godwin’s Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, 1798.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History, edited by Dino Franco Felluga, https://www.branchcollective.org/?ps_articles=ghislaine-mcdayter-on-the-publication-of-william-godwins-memoirs-of-the-author-of-a-vindication-of-the-rights-of-woman-1798.