This post is part of Around the World with Six Women: A Travel Writing Spotlight Series, which will run through August 2021. Spotlights in this series focus on travel writing by women in the database.

Authored by: Hanieh Ghaderi

Edited by: Michelle Levy and Kandice Sharren

Submitted on: 08/06/2021

Citation: Ghaderi, Hanieh. "Agency in Empire: Eliza Fay in India." The Women's Print History Project, 6 August, 2021, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/82.

Figure 1. Thomas Daniell, Views of Calcutta (1788). Plate 9. British Museum.

Figure 1. Thomas Daniell, Views of Calcutta (1788). Plate 9. British Museum.

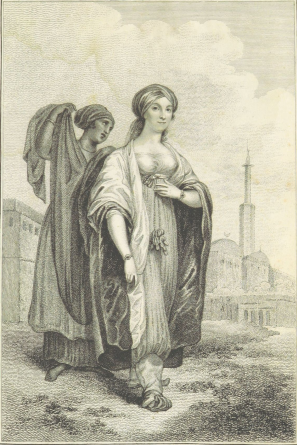

Eliza Fay’s letters about her grueling and adventure-filled journeys to India by land and sea between 1779 to 1796 were published as Original Letters from India (1817) in Calcutta, modern-day Kolkata, shortly after she died in 1816. Born in 1755 or 1756 as Eliza Clement, little is known of her early life. She married Anthony Fay, at the age of sixteen or seventeen, in 1772. Original Letters from India contains letters from three of Fay’s trips to India: her first trip, from 1779 to 1783, which followed her journey through France, across the Alps to Italy, from Leghorn (now Livorno) to Alexandria, Egypt, then to Cairo, across the desert to Suez, and then on to India, where she was captured and taken prisoner due to the war between England and France; her second voyage took place from 1784 to 1794, when she started to engage in local businesses and trading in India; and her third voyage, from 1795 to 1796. The book opens with an engraved frontispiece of Fay in an Egyptian costume. It ends when Fay leaves India for New York in 1796 (404).

Figure 2. Eliza Fay in Egyptian Costume, frontispiece to the second edition, British Library.

Figure 2. Eliza Fay in Egyptian Costume, frontispiece to the second edition, British Library.

In her letters, Fay positions herself as the heroine of her adventures and offers a colorful first-hand account of the events, providing detailed information about her private life as well as the places and people she encounters. Her letters convey her personal character, especially her independence and bravery as if she were a protagonist in a novel, which draws the readers in. Fay’s emphasis on her personal experience is at odds with what Carl Thompson identifies as the primary expectation for travel writing during this period, namely, “reasonably well-informed, factual reportage across a variety of topics; mere frivolity, ostentatious elegance in the writing and excessive sentimental exploration of the writer’s personal feelings were all liable to be dismissed as self-indulgent” (135). The preface to the first edition of Original Letters from India (1817) adheres to modesty tropes common to publications by women in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It has been a conventional practice for many travel writers in the period to reassure the reader that they are not writing for money or fame, and if it was not for the request of friends, they would have never published their work (Colbert 155). In the preface, Fay claims to have had doubts about publishing her letters for fear of criticism, despite persistent encouragement from her friends to publish her adventures. The preface points to the common harsh evaluations of female authors in that era. Citing a cultural shift whereby "a female author is no longer regarded as an object of derision" (v), the preface explains her change of heart. However, the advertisement at the end of the first edition indicates that the book was published posthumously, “with a view of benefitting the estate” (405), suggesting that there was a financial motive for the publication of the letters. The Advertisement also notes that the administrator who took over the publishing subsequent to Fay’s death had opted not to include subsequent parts of her journal, “not appearing to contain any events of a nature sufficiently interesting to claim publication” (405).

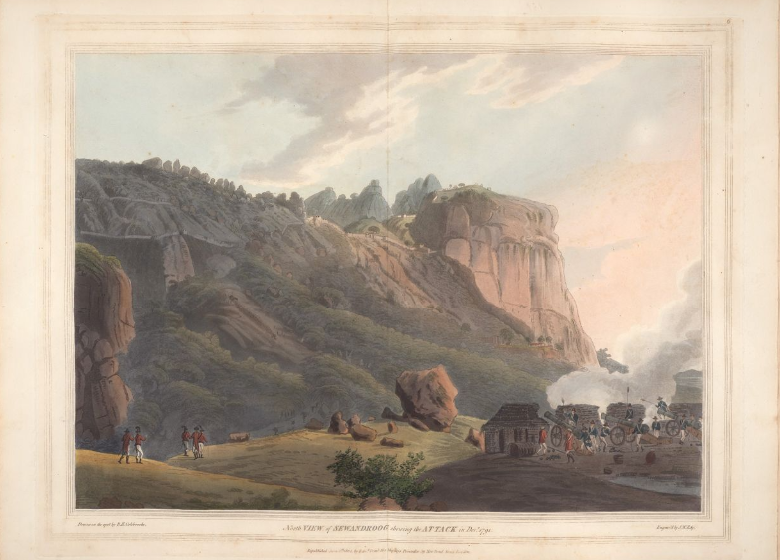

This book, along with the second edition, which appeared in 1821, is one of the only titles in the entire WPHP database that was printed in Kolkata (the other title is Oriental Scenes, Dramatic Sketches, and Tales, with Other Poems). It is not clear who has published these editions. However, that a second edition of the book was called for, in 1821, suggests its popularity and success at the time (O'Loughlin & Gamer 149). The book can be divided into two parts: the first contains letters Fay had written for her family, describing her first voyage in detail. In these letters, dating from 1779 to 1782, she expresses her emotional responses and feelings more openly. For instance, her dissatisfaction with her husband is pronounced in this part. The second part includes reports about her second and third voyages in a more formal and self-consciously crafted way as if she were thinking of publishing them. This part acts as a memoir of her journeys. Fay conveys her high spirits and resourcefulness in describing her passage to India, which included crossing the Alps and caravaning across the Egyptian desert. All of this occurred when Fay was newly married and twenty-three. Upon arriving in Calicut (known now as Kozhikode), the Fays found themselves in the middle of a war between England and France and were captured by an ally of France, Hyder Ally, the ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore In Southern India (Barros & Smith 186). The image below shows one of the later battles in the Mysore war.

Figure 3. Aquatint of Robert H. Colebrook's North View of Sewandroog shewing the attack in Decr. 1791, 1805. National Army Museum.

Her imprisonment at Calicut is an instance in which she presents herself as the heroine of her journeys, showing her narrative power through descriptive language and bold action. She captures her fearlessness in many situations, such as the letter in which she describes how she has saved her husband from Pereira, one of Ally’s officers, during their imprisonment:

I had long marked his hatred to Mr. Fay and dreaded his revenge. I was sitting at work when he [Pereira], naked from the middle, entered the room Just as Mr. Fay was going into the next room. His strange appearance and the quickstep with which he followed my husband caught my attention, and I perceived that he held a short dagger close under his arm nearly all concealed under his handkerchief. The exigency of the moment gave me courage. I sprang between him and the door through which Mr. Fay had just passed, drawing it close and securing it to prevent his return, and then gently expostulated with Pereira on the oddness of his conduct and appearance. He shrunk away, and I hope will never trouble us again. (109)

One may note how this event is narrated to construct Fay as the heroine who saves the day by her bravery. Fay’s detailed description of the way each character looks, Pereira is “naked from the middle,” and her heroic activities, “I sprang between him and the door” are important examples of the ways in which Fay positions herself, rather than factual information about the places she travels to, at the centre of the story.

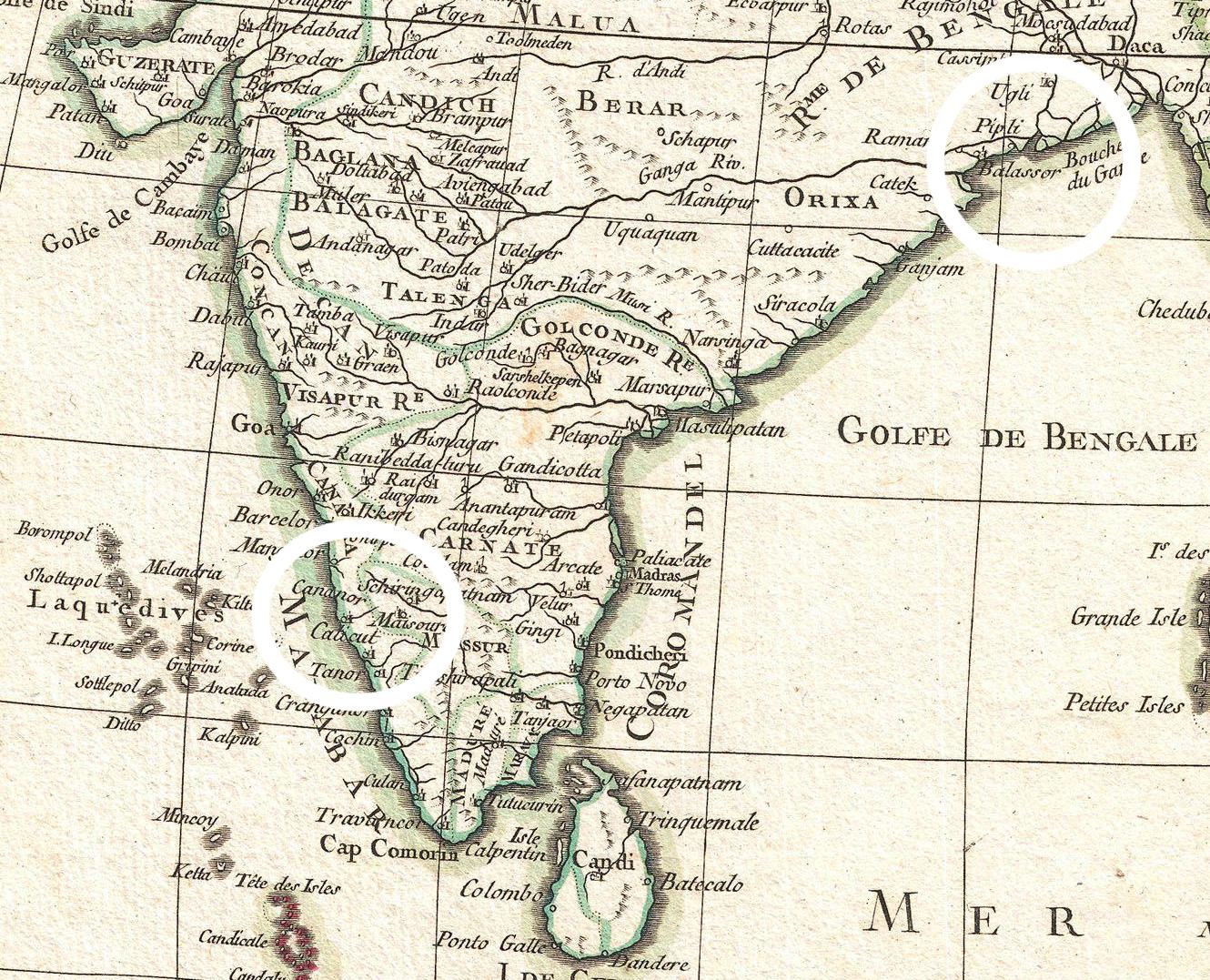

Figure 4. Selection from Rigobert Bonne's 1770 Map of India and Southeast Asia, showing to the west, the port of Calicut, where the Fays landed, and to the East and North, their destination, after travelling by ship to Calcutta. Wikimedia.

The Fays went east to Kolkata soon after their release. The map above shows northern India in the 1780s, with Bangladesh to the east. You can find “Calcutta” in the center of Bangladesh. In Calcutta, Fay’s life underwent profound changes that allowed her to gain greater independence. While there, she found out that her husband had a child with another woman (Barros & Smith 186). By the end of July 1781, Fay’s husband left her, and in the same year, she filed for a legal separation, which was enacted in August (186). Fay captures all these details in her letters (Mickelson-Gaughan 135). She does not just write about her private life, however, but shows great awareness of the political affairs of her time in India, probably since most of them are related to her own life. For instance, Fay talks about affairs in the Carnatic as a result of her previous encounter with Hyder Ally and the fact that she resents him (Mickelson-Gaughan 136). She writes:

We may think ourselves very well off in escaping from the paws of that fell tyger Hyder Ally as we did, for I am assured that the threat of sending us up the country to be fed on dry rice, was not likely to be a vain one; it is thought that several of our countrymen are at this very time suffering in that way: if so, I heartily wish that the War he has provoked, may go forward ‘till those unhappy beings are released and the usurping tyrant is effectually humbled. (231)

Furthermore, some scholars believe that Fay’s separation from her husband also impacted her attention to the political and cultural circumstances around her. Barros and Smith state that after her separation, Fay began to write about patriarchal values that affected Indian women. They argue that this sudden attention can be a result of Fay’s independence from her husband, which has played an important role in her worldview (Barros & Smith 186).

In order to understand Fay's independence and agency, it is necessary to contextualize them in relation to the geopolitical spaces in which she lived. Central to such a line of inquiry is to examine Fay's power and autonomy in India and compare it to her presence in the British Empire. One can see how her experience of independence is shaped and challenged by political and economical influences in each country. In 1783, Fay traveled to England, where she found that she could not achieve the level of economic independence she desired in that country. Her mother had passed away (184), and there was nothing to keep her there. Considering the circumstances, she decided to once again travel to India. After a year, she managed to acquire means for transportation to Bombay by protecting four women during the trip (Barros & Smith 187). A captain let Fay travel with them to India on the condition that she would act as a chaperone. After her arrival, she started to engage in business in Bombay and ran a military business for four years. Fay managed to acquire some property and became a successful tradesperson in Europe and India (187). Fay's ability to be independent was profoundly influenced by her position within the British Empire.

The book remained of interest to readers well into the twentieth century; E.M. Forster, the famous novelist and the author of A Passage to India, republished Fay’s book in 1925 with a critical introduction and annotations. This introduction is valuable as it points to the ways in which the letters reveal Fay's character. Forster describes her letters as “delightfully malicious,” and states that Fay narrates the details of the events in a manner that one may see her personality in every corner of the book. He believes that compared to her fellow travel writers, Fay is notably present in each episode of the stories and every word she writes is a reflection of her character (Introductory notes). Forster also asserts that Fay’s letters both reflect the colonial environment of India in the eighteenth century and her character. He considers Fay “‘in her sense, as in her sentiment, the child of her century” (Forster Introductory notes), explaining that Fay displays the sentimentalism in eighteenth-century literature. He writes that Fay celebrates the emotional aspects of the events she narrates and lets her feelings enter the letters. However, her emotions as well as her lived experience are profoundly impacted and shaped by colonialism in her era.

In English Travellers in Egypt during the reign of Mohamed Ali, M.R. Rushdy writes: "It is in this fidelity to herself, combined with an extraordinary keenness of perception, that the freshness of her writing lies; even the old and familiar theme of the 'ruins of empire' is turned in her hands into something new and lively because she makes us feel it was personal" (Rushdy 48). Fay reflects the colonial atmosphere of her time in the letters, but she also combines it with her sentiments and personal views. Her book does not seek to be an objective narrative of past events. It is a story of Fay's lived experience within the British Empire and her agency in relation to the space in which she lives. Fay's capacity to reflect and act within the colonial atmosphere of her time is well documented in Original Letters from India. She positions herself as the heroine of her book and keeps her personal experiences at the front and center of the historical events that shaped her life.

WPHP Records Referenced

Fay, Eliza (person, author)

Works Cited

Barros, Carolyn A., and Smith. Life-Writings by British Women, 1660-1815: an Anthology. Northeastern UP, 2000.

Colbert, Benjamin. “British Women's Travel Writing, 1780-1840: Bibliographical Reflections.” Women's Writing: the Elizabethan to Victorian Period, vol. 24, no. 2, 2017, pp. 151–69.

Fay, Eliza. Original Letters from India: Containing a Narrative of a Journey through Egypt, and the Author's Imprisonment at Calicut by Hyder Ally: To Which Is Added an Abstract of Three Subsequent Voyages to India. 1817.

Forster, E. M. "Introductory Notes": Original Letters from India: Containing a Narrative of a Journey through Egypt, and the Author's Imprisonment at Calicut by Hyder Ally: To Which Is Added an Abstract of Three Subsequent Voyages to India. 1925.

O’Loughlin, Katrina Éadaoin, and Gamer, Michael. Women’s Travel Writings in India 1777-1854. Routledge, 2020.

Mickelson-Gaughan, Joan. The 'Incumberances': British Women in India, 1615-1856. Oxford UP, 2013.

Rudd, Andrew. “Sympathy in a Hot Climate: British and Indian Subjects at the Turn of the Century.” Sympathy and India in British Literature, 1770–1830. Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2011, pp. 87–116.

Rushdy, M. R., English Travellers in Egypt during the reign of Mohamed Ali (I805-I847); a Study in a Literary Form. 1950. U of Leeds., PhD dissertation.

Thompson, Carl. “Journeys to Authority: Reassessing Women's Early Travel Writing, 1763-1862.” Women's Writing : the Elizabethan to Victorian Period, vol. 24, no. 2, 2017, pp. 131–50.