This post is part of Around the World with Six Women: A Travel Writing Spotlight Series, which will run through August 2021. Spotlights in this series focus on travel writing by women in the database.

Authored by: Isabelle Burrows

Edited by: Michelle Levy and Kandice Sharren

Submitted on: 08/13/2021

Citation: Burrows, Isabelle. "Narratives of Empire: Cultural colonialism in Maria Graham's Journal of a Residence in Chile during the year 1822." The Women's Print History Project, 13 August, 2021, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/83.

Figure 1. Maria, Lady Callcott by Sir Thomas Lawrence, © National Portrait Gallery.

Recently at the WPHP we’ve expanded the genre function in our title records to allow for the selection of multiple genres on a single title record. This function allows us to fully capture the nuances of the works we record, revealing a fuller picture of a work, its purpose, and its contents. Maria Graham’s Journal of a Residence in Chile is one such genre-bending work. Equal parts travel narrative, history, and political document, the journal weaves together varied aspects of Chilean cultural life in the early 1800s. Bending genre boundaries allowed Graham to describe a multi-faceted dynamic between herself, Britain, and Chile that appealed directly to the colonial concerns of British audiences.

When she wrote Journal of a Residence in Chile, Maria Dundas Graham was neither a novice traveller nor travel writer. Crossing genres was as familiar to her as crossing oceans, and her travels carried both her person and her literary career through three continents and across more than a dozen literary works, from her Journal of a Residence in India, based on her travels in 1809, to her Memoirs of the Life of Nicholas Poussin. An author, translator, editor, and critic, Graham was a ready learner and an expert writer, and these qualities made her the perfect representative for Britain’s cause in Chile. Although she arrived there accidentally, after the death of her naval officer husband, Graham wasted no time turning the experience from a tragedy to an opportunity as she recorded and commented on the conditions she observed in her temporary home. A series of often-deposed provisional juntas had secured precarious independence for Chile, beginning in 1810 (Prago 132), so when Graham arrived in 1822, the country was enjoying a period of relative stability. The issue of South American independence, however, was far from resolved: though Chile had officially declared itself independent by 1818 (150) under the direction of Chilean-born patriot Supreme Director Bernardo O’Higgins, neighbouring Peru was still under Spanish administration. The border between colonial control and independence was a constant cause of contention. Graham arrived with the British naval force to which her husband belonged as part of Britain’s effort to mediate this contention, to “preserve . . . amicable relations with the government of Chile . . . so necessary for the protection of the subjects of his Britannic Majesty who are engaged in lawful commerce” (Journal appendices, “Letter from Commander in Chief of the British Navy to Chile’s Minister of Marine” 488).

Journal of a Residence is divided roughly into thirds, consisting of a history of Chile, Graham's personal travel journal, and a series of appendices. Each section serves Graham’s professed narrative of “calling attention” (v) to Chile as a nation in need of foreign cultivation and development. The basis of a British economic future in Chile relied on Chile’s ability to negotiate its own interests autonomously, outside the grasp of Spanish colonial power. Graham’s portrayal of Chile’s struggle for independence “reconstruct[s] the region’s past in order to secure Britain’s place in its economic future” (Caballero 119) by positioning Britain as not just a friendly trade partner, but as an agent of liberation in Chile’s history, and thus worthy of favour and attention from the newly independent nation. Graham casts Britain (nominally neutral in the South American colonial wars) (Caballero 114) as a great friend of Chilean national independence from the country's earliest years. In her history of Chile, Graham emphasizes the war of independence above all other matters, and attributes eventual victory over Spanish rule to Supreme Director Bernardo O’Higgins’ education in England, “where he had not only learned the language perfectly, but a good deal of the free and independent spirit of the nation” (16). Similarly, she paints her friend the Admiral Lord Cochrane, a naval officer involved first in Chilean independence and then the war for the liberation of Spanish-held Peru, as a hero who “ought to have influence to mend some things . . . which, without such influence, will, I fear, prove highly detrimental to the rising state of Chile if not to the general cause of south American independence” (147). The dynamic of Chile as an infant nation in need of support from the more developed and civilized Britain underpins Graham’s narrative, in which she pronounces herself “too old not to be afraid of ready-made constitutions, and especially of one fitted to the habits of a highly civilized people applied too suddenly to an infant nation like this” (147–48). The implication of this statement is that Chile requires the presence of more developed nations like Britain to achieve effective self-government. This narrative paints British presence in the region as not just beneficial, but necessary. By expressing these sentiments under the labels of historical fact and personal observation, Graham legitimizes her opinions as the foundations of a dynamic of superiority that continues to this day, ensuring that the progression of Britain’s interference in South America is presented in a credible way.

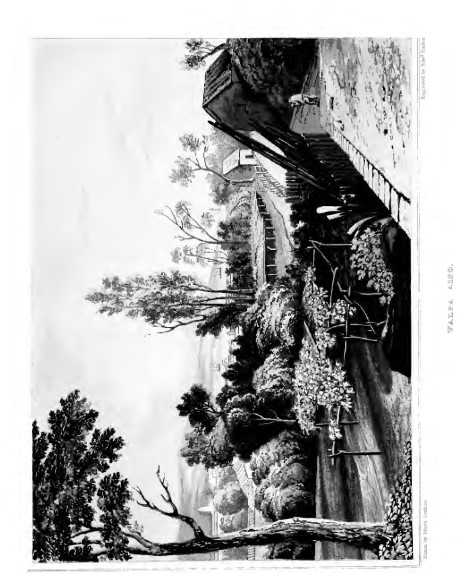

Figure 2. View of Valparaiso, drawn, like the other prints featured in this article, by Graham herself.

While Graham probably didn’t see the Journal as a piece of propaganda, the work is certainly a product of the colonial circumstances in which it was written. It is a conscientious exercise in genre manipulation, and Graham’s self-professed purpose in writing it is political:

There can be no doubt of the ultimate success of their [the Chileans’] endeavours after a free and flourishing state: but there are no ordinary difficulties to get over…If the following pages shall in the slightest degree contribute directly or indirectly to supply those wants, or to smooth those difficulties, by calling attention to that country, either as one particularly fitted for commercial intercourse, or as one whose natural resources and powers have yet to be cultivated, the writer will feel the truest satisfaction. (v)

Graham doesn’t state whose attention she is calling to Chile, but the purpose of calling that attention is clearly to show the economic and political potential of Chile as a region ripe for resource extraction, largely uncultivated, and open to colonization. It is this mission which guides Graham’s presentation of Chile, of herself, and of her British colleagues in the new world. Her ability to present this narrative in a believable way is aided by her choice of form and genre. The nuances of the travelogue, which by its nature allows the inclusion of a variety of topics subject to the author’s observations, seems to convey truth directly from her lived experience to the public (Baudino 3), while the genres of history and political writing carry the illusion of academic accuracy. Graham reminds the reader within the journal portion of the text that “the journal is true; true to nature, true to facts . . . This truth I solemnly engage myself to preserve” (146). In short, she insists that the detailed picture she is painting of Chile is a completely accurate one.

Graham’s independent spirit and acuity of observation made her a master of the travel genre, and her journal balances idealization of British actions with believably detailed observations of local events to create an account that appealed to the curious public at home. Graham’s records of her travel in South America gave her first-hand experience that made her contributions useful to the scientific community in Britain, as evidenced by the publication of her account of the earthquakes of 1822 in the Transactions of the Geological Society Journal (Thompson 329), as well as the use of her botanical drawings and samples by the director of Kew Gardens (Manthorne, “Female Eyes on South America”). While this increased participation by women like Graham in travel, science, and politics was a welcome step forward in independence for them, the exploration Graham participated in with so much aplomb was a facet of colonial expansion and exploitation. Maria Graham was only one of the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century women explorers (including Maria Sibylla Merian, Elizabeth Cary Agassiz, and Ida Pfeiffer, to name a few; Dr. Katherine Manthorne’s scholarship on these women is linked below) whose literary and artistic records of travel in South America were exported back to Europe in service of colonial rhetoric. Such works facilitated more effective colonial relationships by creating “public knowledge [in Europe] about foreign spaces; they were in many ways, the narratives of the empire” (Caballero 115). While a woman’s botanical drawings or written description of her environs might seem benign, to dismiss such works as decorative or trivial would be to ignore their efficacy as tools of both empiricism and empire. Journal of a Residence in Chile, with its political undertones and carefully curated illustration of foreign culture, clearly aids Britain’s self-interested presence in South America.

Figure 3. Graham's view of Laguna de Aculeo, showcasing the vast, rich, and, to European eyes, underutilized landscapes of the region.

Figure 3. Graham's view of Laguna de Aculeo, showcasing the vast, rich, and, to European eyes, underutilized landscapes of the region.

Like the travelogue and history sections of the Journal, the final section of collected political documents emphasizes not just Britain’s significant contributions to economic and political development in Chile and adjacent regions, but also Britain’s right to continue that interference. As she does in the history section, Graham shows her friend Lord Cochrane as a paragon of British honour and intellect, “the embodiment of her civilising model” (Caballero 112) of cultural improvement rather than explicit exploitation. The inclusion of a document from the new independent junta of Peru, thanking Cochrane for “services rendered to Peruvian freedom by the Right Honourable the Lord Cochrane,—owing to whose genius, worth, and bravery, the Pacific is freed from the insults of enemies” (486) leaves little room for doubt in the minds of readers that British men like Cochrane were doing nothing but good for the “uncivilized” nations of the new world.

Cultivation and development of the land in the name of civilization are the primary reasons that Graham presents as evidence of Britain’s beneficial influence in Chile. While the ideals of civilization (both of land and of minds) appealed to Graham, she was careful to align herself in her writing with the intellectual side of this development rather than with the unpleasant realities of the commercial and industrial expansion, which she disparaged. Even though her “presence [as an agent of British interests] fundamentally aligns her with these 'incurious money makers' and depends upon safeguarding the ‘very low scale’ of British tradesmen in the region” (Caballero 122), Graham associates herself almost exclusively with British intellectual culture and civilization. She draws a clear line between the beneficial British culture exemplified by fellow women writers with whom she identifies as she expresses her pride in “[belonging] to the sex and nation, which will furnish names to engage the reference and affection of our fellow-creatures as long as virtue and literature continue to be cultivated” (140). Names like Anna Laetitia Barbauld, Sarah Trimmer, and Maria Edgeworth are among Graham’s examples of correct British cultural influence, while the British tradesmen in Chile are uniformly derided and condemned as “specimens of such [vulgar] people as one meets nowhere else but among the Brangtons, in Madame d’Arblay’s Cecilia, or the Mrs. Elton’s of Miss Austin’s admirable novels” (180). By framing herself as an agent of culture and learning, Graham elides the economic, political, and cultural aspects of Britain’s interference into a single mission of magnanimous civilization. Shifting responsibility for visibly exploitative economic actions onto the “lower” classes of British society, Graham frames her own colonial agenda of artistic and intellectual erasure and reeducation as philanthropic. “I am sorry,” she writes, “that they [the Chilean people] have something of more pressing importance than the fine arts to attend to” (178–79), suggesting that only by abandoning what she sees as “primitive” modes of subsistence living for “civilized” (British) ones can Chilean society expect to pursue artistic and intellectual development.

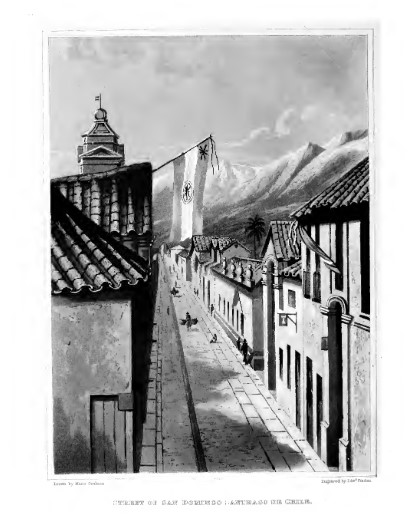

Figure 4. View of a street in Santiago.

Figure 4. View of a street in Santiago.

Because the failure to achieve civilization was attributed to “ the failure to rationalize, specialize, and maximize production” (Pratt 148), Graham presents observations of Chile’s economic and cultural status which require not just a practical, but an ideological, solution. Graham’s note that “The immediate wants of Chile are education in the upper and middling classes, and a greater number of working hands . . . Not a hundredth part of the soil is cultivated” (158) demonstrates her belief that the “civilizing” mission involves not just industrial and agricultural developments, but the implementation of the stratified education system on which “developed” countries like her own relied. Quoting an address from Supreme Director Bernardo O’Higgins to the Peruvians, in which he emphasizes economic development and international trade as the advantages and causes of liberty in independent countries, Graham supports her continuing claim that independence and civilization necessitate resource extraction and industrial development: “They [independent nations] enjoy the fruits of their liberty; and are considered by the nations of the universe, who emulously bring to them the products of their industry” (Journal 475, from “The Supreme Director of the State of Chile to the Natives of Peru”). By referencing this speech, Graham fully realizes the narrative of economic development as civilization. England, a “ready-civilised country in Europe, where the niggard earth yields not wherewithal to trade” (290), is at the height of civilization, having fully extracted all of its natural resources and graduated to industrial manufacture. Meanwhile, Chile and its neighbours are just beginning this journey, flowing with precious metals and agricultural products which, with Britain’s help, will fuel their rise to the European ideal of nationhood. This conflation of economic development with political autonomy successfully merges the ideological and the practical improvements which Graham believes Britain will, and should, introduce in Chile.

WPHP Records Referenced

Graham, Maria (person, author)

Journal of a Residence in Chile (title)

Journal of a Residence in India (title)

Memoirs of the Life of Nicholas Poussin (title)

Austen, Jane (person, author)

Barbauld, Anna Laetitia (person, author)

Trimmer, Sarah (person, author)

Edgeworth, Maria (person, author)

Burney, Frances (person, author)

Cecilia (title)

Works Cited

Baudino, Isabelle. “Nothing seems to have escaped her:’ British Women Travellers as Art Critics and Connoisseurs (1775–1825). 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century, no. 28, 2019, n.p.

Caballero, M. Soledad, “‘For the Honour of Our Country:’ Maria Dundas Graham and the Romance of Benign Domination.” Studies in Travel Writing, vol. 9, no. 2, 2005, pp. 111–31.

Graham, Maria. Journal of a residence in Chile during the year 1822. Longman, 1824.

Manthorne, Katherine. “Female eyes on South America: Maria Graham,” Collecion Cisneros, July 21, 2017, accessed August 4, 2021, https://www.coleccioncisneros.org/editorial/cite-site-sights/female-eyes-south-america-maria-graham#.YQMaXzg0BJ4.link

Prago, Albert. The Revolutions in Spanish America: the independence movements of 1808-25, Macmillan, 1970.

Pratt, Mary Louise. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation, 2nd ed., Routledge, 2007.

Thompson, Carl. “Earthquakes and Petticoats: Maria Graham, Geology, and Early Nineteenth-Century ‘Polite’ Science.” Journal of Victorian Culture, vol. 17, no. 3, 2012, pp. 329–46.

Further Reading

Manthorne, Katherine, “Female Eyes on South America: Maria Sibylla Merian in Surinam, 1699–1701,” Collecion Cisneros, 2017, https://www.coleccioncisneros.org/editorial/cite-site-sights/female-eyes-south-america-maria-sibylla-merian-surinam-1699%E2%80%931701

“Female Eyes on South America: Elizabeth Cary Agassiz (1822–1907),” Collecion Cisneros, 2017, https://www.coleccioncisneros.org/editorial/cite-site-sights/female-eyes-south-america-elizabeth-cary-agassiz-1822%E2%80%931907

“Female Eyes on South America: Ida Pfeiffer (1797–1858),” Collecion Cisneros, 2017, https://www.coleccioncisneros.org/editorial/cite-site-sights/female-eyes-south-america-ida-pfeiffer-1797%E2%80%931858