This post is part of Around the World with Six Women: A Travel Writing Spotlight Series, which will run through August 2021. Spotlights in this series focus on travel writing by women in the database.

Authored by: Victoria DeHart

Edited by: Michelle Levy and Kandice Sharren

Submitted on: 08/20/2021

Citation: DeHart, Victoria. "Sarah Belzoni’s (Not So) Trifling Account of Women in Egypt, Nubia and Syria." The Women's Print History Project, 20 August 2021, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/85

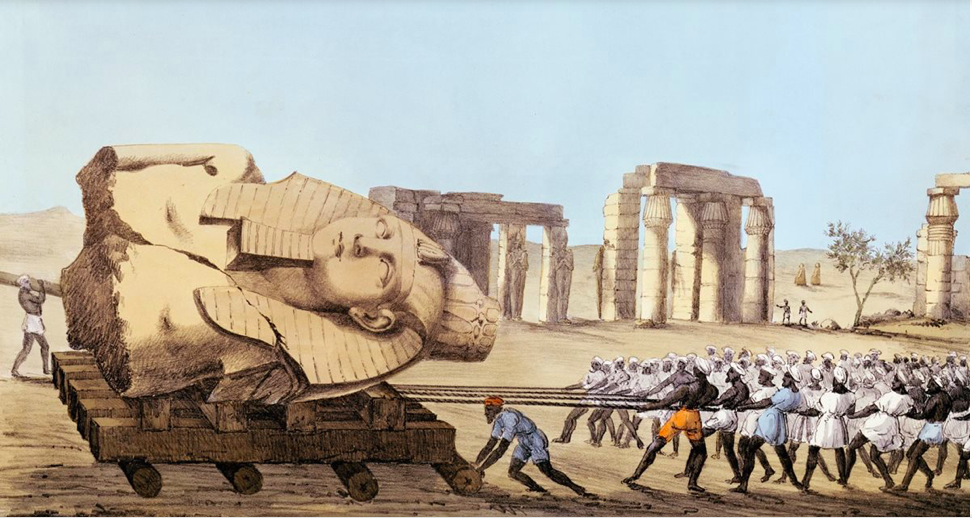

Figure 1. Removal of the statue of Ramses II, also known as The Younger Memnon. AramcoWorld.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, antiquarianism, or the study and collection of antiquities, was a field largely dominated by men. On very rare occasions we find a woman engaging in antiquarian pursuits, they are usually known only through the achievements of their male associates or husbands. Such is the case of Sarah Belzoni (1783–1870), who married Egyptologist Giovanni Battista Belzoni (1778–1823) in 1803 (Peck 1).

Little is known about Sarah Belzoni’s early life—her maiden name is believed to be Banne and her birthplace either Bristol or Ireland (Peck 1-2). After her marriage, Sarah Belzoni accompanied her husband through the British Isles and Europe while he performed as a circus strongman. The couple left Europe and arrived in Cairo in 1815, where they met Henry Salt, the British Consul to Egypt. Salt employed Belzoni as an engineer to remove an ancient statue of Ramesses II, also known as The Younger Memnon, from Thebes; this event marked the beginning of Giovanni Belzoni’s career as an antiquarian and the beginning of Sarah Belzoni’s travelogue, Mrs. Belzoni’s Trifling Account of the Women in Egypt, Nubia and Syria (1820).

Although a divisive figure amongst archaeologists today due to his destructive techniques, his leaving of graffiti at the tombs he discovered, and his plundering of artifacts, Giovanni Belzoni is nevertheless considered a pioneer archaeologist and the father of modern-day Egyptology. In addition to his career as a circus strongman, he pursued different paths as an engineer, explorer, and antiquarian. He discovered the entrance to the pyramid, Khafre, of the Giza Pyramid Complex; revealed the entrance of the great temple at Abu Simbel; discovered the tomb of Seti I in the Valley of the Kings; and successfully identified the ruins of the ancient seaport Berenike, on the Red Sea (Park 1). During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, antiquarianism became an endeavor tied to Britain's empire-building; Giovanni Belzoni became the main agent of Henry Salt to secure antiquities and objects for the British Museum to showcase the extent of England's reach in the Middle East. While Sarah Belzoni often accompanied her husband on his excursions, she was also left on her own for long periods of time, during which she took the opportunity to visit with local women and explore the cities and villages on her own (Peck 2; Colbert).

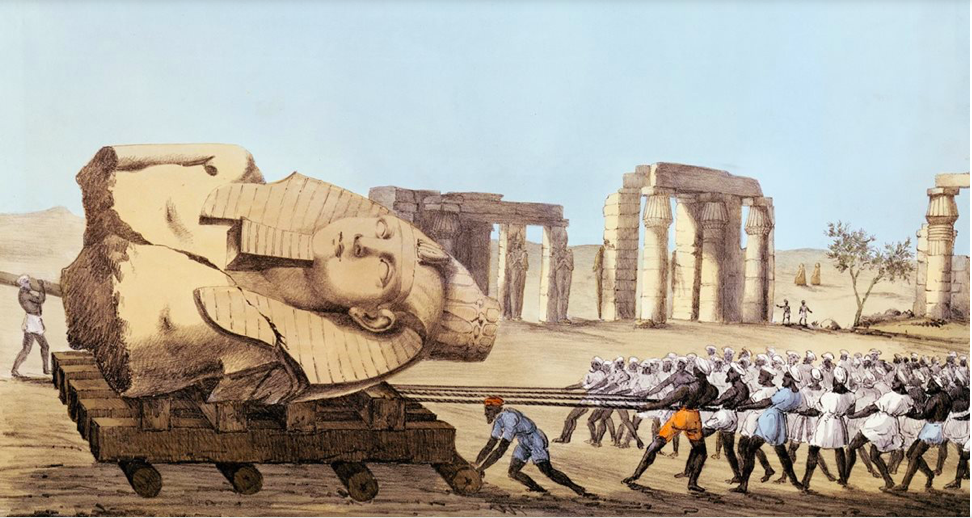

Figure 2. Engraving of Sarah and Giovanni Belzoni in a Bark in the middle of the Cataract, featured in Wilson’s Fruits of Enterprise (1841). Wikipedia.

While her husband was working in Thebes, Belzoni stayed in Luxor for two months without an interpreter and “about twenty Arab words in [her] mouth” (449). Although she could hardly communicate, Belzoni established a rapport with the local women, who daily came to “look, talk and trade antique beads for modern ones” (Manley 1). During her stay, she was struck with a severe case of ophthalmia and completely lost her vision for a period of time. Belzoni was helped by the local women who persuaded her to steam her face over hot water and garlic; the remedy appears to have aided in her recovery and helped her to regain her sight (451).

In 1818, Belzoni writes, "I persuaded Mr. B. to let me visit the Holy Land" (457). The descriptions of her journey give us a remarkable glimpse into travel of the Middle East and the practices of pilgrims during the nineteenth century (Peck 1). In the company of an Irish attendant, James Curtain, she arrived in Jaffa in mid-march to witness the last days of Holy Week. In May, she left for Jordan by mule and participated in the Jordan pilgrimage before continuing to Jericho, Nazareth, and Bethlehem. Before leaving Jerusalem, Belzoni dressed in the disguise of a Muslim man and visited the Temple of Jerusalem, a place where non-muslims and women were banned entrance; she quickly left for Cairo in fear of punishment (468). Belzoni remained on her own in Cairo for two months as her husband continued work in Philae; she decided to travel to Luxor where she was informed that the Tomb of Seti had suffered from severe flooding. She entered the tomb and had the mud removed lessening the extent of the damage. She reunited with Giovanni Belzoni in December (474).

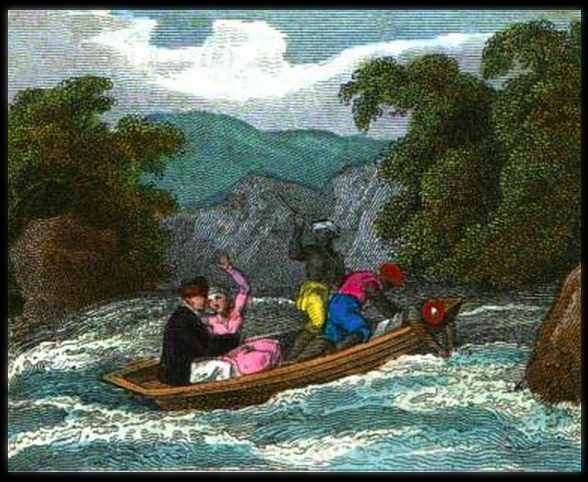

Figure 3. The Younger Memnon; removed by Belzoni in 1816 and acquired by the British Museum in 1821. Currently held in the British Museum, Museum Number EA19.

In September of 1819, the Belzonis left Egypt for England (437). They were preceded by the news of the statue’s removal and rumours swirled of Giovanni Belzoni’s exploits. Narrative of the Operations and Recent Discoveries within the Pyramids, Temples, Tombs, and Excavations, in Egypt and Nubia (1820), written and published quickly by the Belzonis return to England as other explorers and antiquarians were taking credit for Belzoni’s achievements (v; ix). The book was a tremendous success in England and Europe. It was first published in London in 1820, then published a second and third time in 1821 and 1822. The travelogue proved to be as popular in continental Europe; it was translated into French, Dutch and Italian, appearing in Paris in 1822, Groningen in 1823, and Milan in 1825; and was published in English in Brussels in 1835. In addition to the book, Giovanni Belzoni published a series of illustrative plates in 1820 and 1822, which proved to be equally popular. It is probable that Sarah Belzoni helped her husband to write the book despite his claim that Narrative of the Operations was his own work (v–vi). English was not Belzoni’s first language, and, as noted by Megan Price, Belzoni’s account “displays marked differences” in style from his existing letters in circulation today (Price 2008).

Mrs. Belzoni’s Trifling Account, roughly forty pages, is appended to the end of Narrative of the Operations. Despite the briefness of her travelogue, it is considered a trailblazing account of Egypt and the “first of its kind” by many because of her descriptions of the everyday lives of local women in early-nineteenth century Egypt and Palestine (Manly 1; Peck 2). Never before had the practices, customs, and possessions of local women in Egypt and Palestine been recorded by an English woman (Peck 2). Although a fascinating work, Belzoni presents a very anglocentric view of Egyptian and Middle Eastern societies. Her travelogue is innately biased towards Western Civilisation and she brands the different cultures she encounters as “wild” and “immoral” (441; 482). Many of her actions she describes are equally disrespectful; Belzoni disguised herself and snuck into the Temple of Jerusalem, a space where women were not allowed entry at the time, causing much distress for both the Muslim and Christian populations in Jerusalem; and in one instance, she obtains Bibles from the British consul and dispenses them to the local people of Rosetta as a means of spreading Christianity (482).

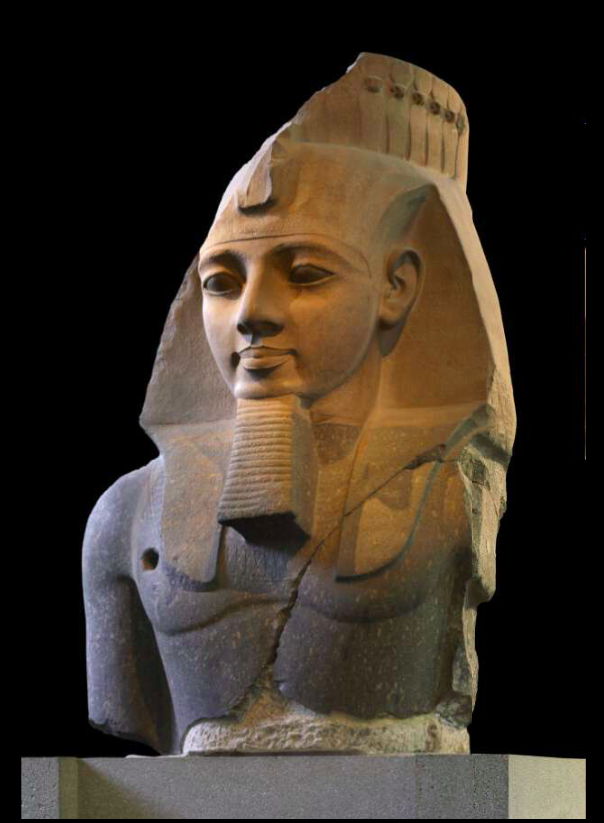

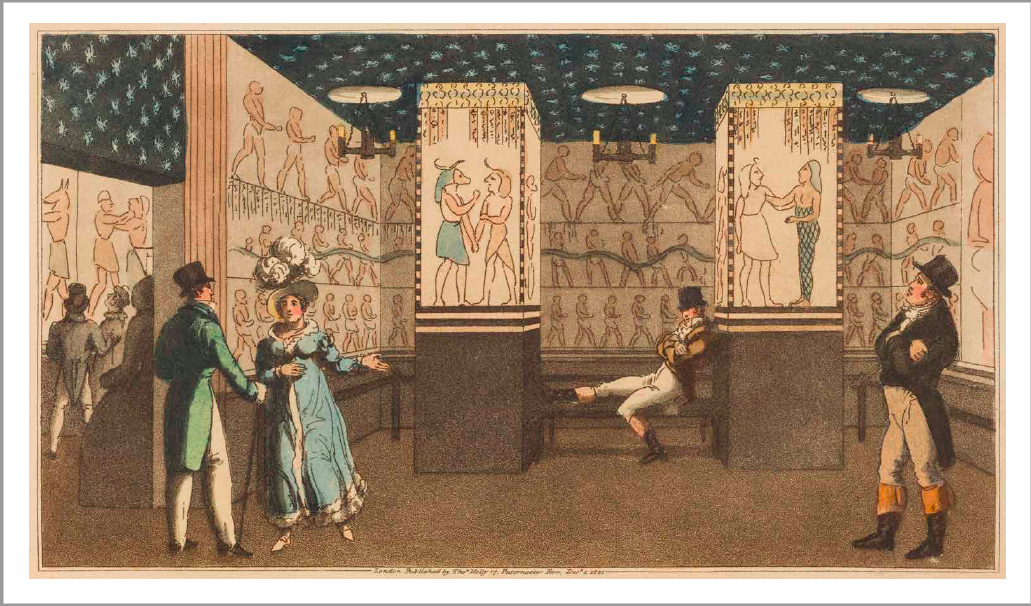

Figure 4. Drawing of Giovanni and Sarah Belzoni’s public exhibition of the Tomb of Seti, featured in Don Juan in London (1822) by Andrew Thornton. Factum Foundation.

Giovanni Belzoni’s involvement in the removal of the statue of Ramses II and the successes of the travelogue and plates made the couple famous in London society and helped spur the Egyptomania of the early nineteenth century (Moser 1289). The excitement surrounding the statue’s arrival in London alone is said to have inspired a friendly competition between Percy Bysshe Shelley and Horace Smith; both poets published a sonnet entitled “Ozymandias” in 1818, exploring the fleeting nature of power. Smith later wrote a second poem entitled, “Address to the Mummy in Belzoni’s Exhibition,” published in 1826.

The Belzonis also prepared and curated an immensely popular public exhibition of the tomb of Sethi I. The exhibition included casts, mummies and other objects recovered from Egypt, as well as life-sized reconstructions of the tomb painted in watercolour (Peck 4). Their most famous exhibition took place in Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly, in 1820, and caused a sensation amongst the public (Moser 1289). Dr. Stephanie Moser, Professor of Archaeology at the University of Southampton, notes that in the 1820s in England and France, there was a surge in the popularity of decorative products that used Egyptian motifs and style, particularly for furniture and clock making (Moser 1289).

Narrative of the Operations’ influence reached even to children’s literature in the 1820s. In 1821, with permission from Giovanni Belzoni, Lucy Atkins Wilson published Fruits of Enterprise Exhibited in the Travels of Belzoni. The novel reached a much larger audience than Narrative of the Operations and centres around the adventures of both Sarah Belzoni and her husband. Fruits of Enterprise proved to be one of Wilson’s most successful works; at least eight editions of the novel were published between 1821 and 1830; six in London (1821; 1822; 1823; 1824; 1825; 1830), one in Paris (1823), and one in Boston (1824). Children’s author Barbara Hofland also included Sarah Belzoni in her work, Africa Described published in 1826.

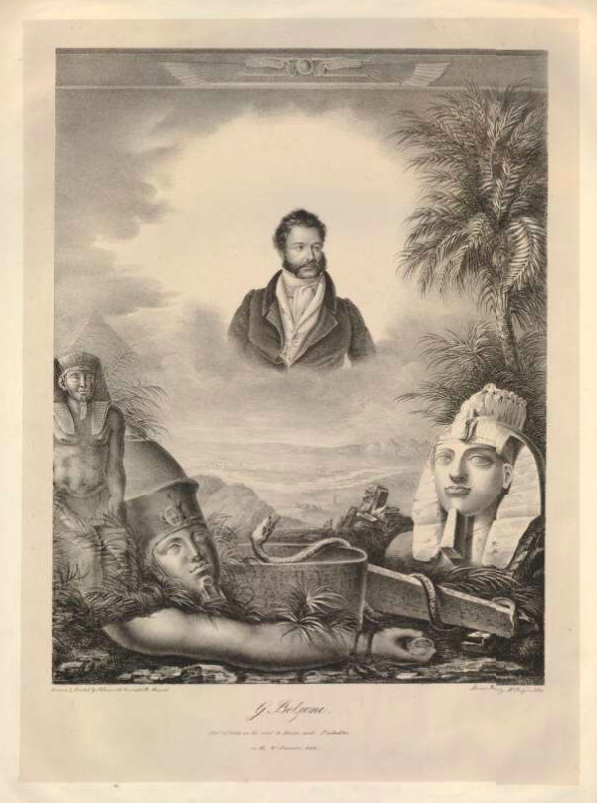

Figure 5. Portrait of Giovanni Belzoni (1824) by F. Fabriani; commissioned and published by Sarah Belzoni after her husband's death in 1823. Held in the British Museum, Museum Number 1888,0716.307.

Sarah Belzoni accompanied her husband on one final adventure to West Africa. She was left on her own in Morocco while he tried to find the source of the Niger River. Giovanni Belzoni fell ill with dysentery and died at Benin in December of 1823 (Peck 4). Sarah Belzoni returned to England and promoted her husband's achievements but faced severe financial difficulty (Waanders 2). On her own, she organised an exhibit of the Tomb of Seti in London and sold many of the objects recovered from Egypt, including an alabaster sarcophagus of Seti I to Sir John Soane (Waanders 2). The exhibition closed in 1825 and she tried unsuccessfully to publish her husband's drawings of the tomb in 1828 (Manley 2). The Royal Literary Fund awarded Belzoni £50 in 1823, and an additional £25 in 1833 for her contributions to Narrative of the Operations. It was not until 1851 when Sarah Belzoni was awarded a Civil List pension by the British government for a yearly sum of £100, lessening her financial difficulty (Waanders 2; Peck 5).

Much like Sarah Belzoni’s early life, there is little information available concerning her later years after her husband passed. She left for Brussels around 1833 and likely lived there until 1854. In 1857, it appears Belzoni moved to Jersey, where she remained until her death on January 12th, 1870, at the age of eighty-seven. After several attempts to locate her tombstone in Jersey; it was finally found in 2011 and restored (Waanders 2).

WPHP Records Referenced

Belzoni, Sarah (person, author)

Belzoni, Giovanni Battista (person, author)

Narrative of the Operations and Recent Discoveries within the Pyramids, Temples, Tombs, and Excavations, in Egypt and Nubia (title, first edition)

Narrative of the Operations and Recent Discoveries within the Pyramids, Temples, Tombs, and Excavations, in Egypt and Nubia (title, second edition)

Narrative of the Operations and Recent Discoveries within the Pyramids, Temples, Tombs, and Excavations, in Egypt and Nubia (title, third edition)

Voyages en Egypte et en Nubie, Contenant le Récit des Recherches et Découvertes Archéologiques Faites Dans les Pyramides, Temples, Ruines et Tombes de ces Pays (title, first French Edition)

Shelley, Percy Bysshe (person, author)

Wilson, Lucy Sarah Atkins (person, author)

Fruits of Enterprize Exhibited in the Travels of Belzoni in Egypt and Nubia: Interspersed with the Observations of a Mother to her Children (title, first edition)

Fruits of Enterprize Exhibited in the Travels of Belzoni in Egypt and Nubia: Interspersed with the Observations of a Mother to her Children (title, second edition)

Fruits of Enterprize Exhibited in the Travels of Belzoni in Egypt and Nubia: Interspersed with the Observations of a Mother to her Children (title, third edition)

Fruits of Enterprize Exhibited in the Travels of Belzoni in Egypt and Nubia: Interspersed with the Observations of a Mother to her Children. To which is added a short account of the Travellers death (title, fourth edition)

Fruits of Enterprize Exhibited in the Travels of Belzoni in Egypt and Nubia: Interspersed with the Observations of a Mother to her Children. To which is added a short account of the Travellers death (title, fifth edition)

Fruits of Enterprize Exhibited in the Travels of Belzoni in Egypt and Nubia: Interspersed with the Observations of a Mother to her Children: to which is added a short account of the Travellers death (title, sixth edition)

L'Égypte et la Nubie, ou Curiosités de ces pays: tirées du voyage de Belzoni (title, first French edition)

Fruits of Enterprize Exhibited in the Travels of Belzoni in Egypt and Nubia, interspersed with the Observations of a Mother to her Children (title, first American edition)

Hofland, Barbara (person, author)

Works Cited

Belzoni, Giovanni, and Sarah Belzoni. Narrative of the Operations and Recent Discoveries within the Pyramids, Temples, Tombs, and Excavations, in Egypt and Nubia. John Murray, 1820

Manley, Deborah. “Belzoni, Sarah (1783-1870), traveller.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford UP, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/52064

Colbert, Benjamin. “Sarah Belzoni.” Women’s Travel Writing, 1780-1840: A Bio-Bibliographical Database, designer Movable Type Ltd, <https://btw.wlv.ac.uk/authors/1012>

Moser, Stephanie. "Reconstructing Ancient Worlds: Reception Studies, Archaeological Representation and the Interpretation of Ancient Egypt." Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, vol. 22, no. 4, 2015, p. 1263–1308.

Peck, William H. “Sarah Belzoni (1783-1870).” Breaking Ground: Women in Old World Archaeology, 2004, <https://www.brown.edu/Research/Breaking_Ground/bios/Belzoni_Sarah.pdf>

Price, Megan. “A Buried Woman of Egyptology.” Bluestocking: Online Journal for Women’s History, 2008, <https://blue-stocking.org.uk/2008/06/01/a-buried-woman-of-egyptology/>

Waanders, Ingeborg. “Sarah Belzoni, Some New Additional Biographical Notes.” Armenian Egyptology Centre Newsletter, vol. 22, 2012, <https://www.academia.edu/1466482/Sarah_Belzoni_some_new_additional_biographical_notes>

Further Reading

Becker, Alida. “The Archaeologist as Titan.” New York Times, 2011.

Fagan, Brian. The Rape of the Nile: Tomb Robbers, Tourists, and Archaeologists in Eygpt. Basic Books, 2009.

Fasick, Adele. “Sarah Belzoni; Another Forgotten Wife.” Teacups and Tyrants, 2012, <https://teacupsandtyrants.com/2012/05/20/sarah-belzoni-another-forgotten-wife/>

Hume, Ivor Noel. Belzoni: The Giant Archaeologists Love to Hate, U of Virginia P, 2011.

Vickers, Mary F. Women Adventurers 1750-1900: a Biographical Dictionary with Excerpts from Selected Travel Writings. McFarland & Company, 2008.