This post is part of our Women & Philosophy Spotlight Series, which will run through March 2022. Spotlights in this series focus on women philosophers in the database.

Authored by: Isabella (Belle) Eist

Edited by: Michelle Levy and Kandice Sharren

Submitted on: 03/11/2022

Citation: Eist, Isabella. “Reprinting Margaret Cavendish.” The Women’s Print History Project, 11 March 2022, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/100.

Figure 1. Pieter van Schuppen after Diepenbeeck. Portrait of Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle. 1800, Wikimedia Commons.

As a woman writer who repudiated the gendered expectation for authorial anonymity, Margaret Cavendish [née Lucas], Duchess of Newcastle (1623–1673), faced criticism and social sanction for publishing without a pseudonym and for writing on natural philosophy, politics, and society, topics considered improper for women to address during and after her lifetime. In response to “malicious” allegations that Cavendish—as a woman who received a gendered and informal education—could not have theorized philosophy, medicine, and astronomy as deftly as she had in her early publications, her husband William Cavendish announced: “here’s the crime, a Lady writes them, and to intrench so much upon the male prerogative, is not to be forgiven” (The philosophical and physical opinions written by Her Excellency the Lady Marchionesse of Newcastle iii). Cavendish spent her adult life crafting an impressive corpus and archival legacy centered around the literary “male prerogative.” Her disregard for the mores of a patriarchal society and print industry that chiefly amplified the voices of privileged men likely influenced the neglect and censorship her important contributions to scientific and proto-feminist discourse received after her death. Despite her husband’s defence, the negative perception of Cavendish carried from her coeval critics into the twentieth century, leading Virginia Woolf to describe her as a “giant cucumber [that] had spread itself over all the roses and carnations in the garden and choked them to death,” because the “crazy Duchess became a bogey to frighten clever girls with” (A Room of One’s Own 73). During the entire period the WPHP covers, the long eighteenth century (1700–1836), the posthumous publication of Cavendish's writing is limited to only six titles that feature her excerpts.

Cavendish’s first two publications, Poems, and Fancies written by the Right Honourable, the Lady Margaret Newcastle and Philosophicall Fancies. Written by the Right Honourable, the Lady Newcastle, were privately printed in 1653. Both of these works reveal the depth of Cavendish’s interest in natural philosophy and lay the groundwork for her later works, such as The Blazing World (1666), which is now regarded as one of the earliest examples of the proto-science fiction novel. These texts are primarily philosophical and moral, as she considers the nature of atoms and matter, the ethos of people and animals, and the intersection of reason, fate, and religion. Over the next twenty years of her life, Cavendish published eleven additional original works, which she continually revised in heavily altered subsequent editions. Despite the exile and financial instability she experienced after her marriage to William Cavendish, a fellow Royalist and general of Charles I, her precarious position did not free her from the social expectation for the lives and productions of upper-class women to remain private and rooted in the domestic sphere (“Margaret Cavendish” 1). Cavendish was known for being “naturally bashful” and quiet during her time in Queen Henrietta Maria’s court, but her shy nature did not extend to her literary ambitions (A True Relation of the Birth, Breeding, and Life, of Margaret Cavendish 21). She remained undiscouraged by the censure of others and continued to write on topics that had been long hegemonized by male writers and patriarchal convention. Cavendish's decision to publish under her name was particularly scandalous; in “Print and Perception,” Tamara Tubb situates Cavendish’s desire to promulgate her privately-published works as an indecent “act of physical exposure,” unbecoming to her status as an aristocratic woman. Though Cavendish was critiqued for her unconventional writing style, supposed vanity, and focus on philosophy, Tubb notes that she can be viewed as “one of the first literary celebrities” in England. Because eccentricity is a quality commonly associated with Cavendish’s literary persona, her short-lived popularity was likely built around the unusual role she occupied, rather than for her talents.

Though Cavendish published a variety of works across different genres and forms, and inevitably grew into her talents as an author over two decades of writing, it is from her first work, Poems, and Fancies, that the majority of her republished excerpts were taken during the long eighteenth century. Poems, and Fancies, and Cavendish herself, garnered a mixture of reproach and admiration from her exclusively male republishers. Ongoing criticism can be witnessed in the equivocal commentary of her early nineteenth-century editor, Sir Samuel Egerton Brydges, who compiled and edited two publications of her works as an “early and brief exhibition” of the private press he partnered with and reluctantly funded (Select Poems i). Recognizing that all the publications of Cavendish’s writing in the WPHP feature a selection based upon the whims of the compiler, modern readers are reminded that republishing only a small portion of an author’s work can distort its meaning and challenge an author’s agency over their writing. Tubb highlights that Cavendish manipulated the prefatory and paratextual material in her publications (such as her specifically commissioned frontispieces) to define herself as a new type of author and “locat[e] her personal authority within her texts.” Tubb argues that Cavendish’s prefaces were crafted to reassert her authorial agency and power over her writing, and went beyond simply introducing herself and her work. Following her death, the fragmentary publication of Cavendish’s writing in short excerpts, without these paratextual materials, undercut her influence over her work and hindered her efforts to destigmatize female authorship. Indeed, it is only now that a complete, critical edition of Cavendish’s writing is in preparation (The Complete Works of Margaret Cavendish).

Republishing and Refashioning Cavendish

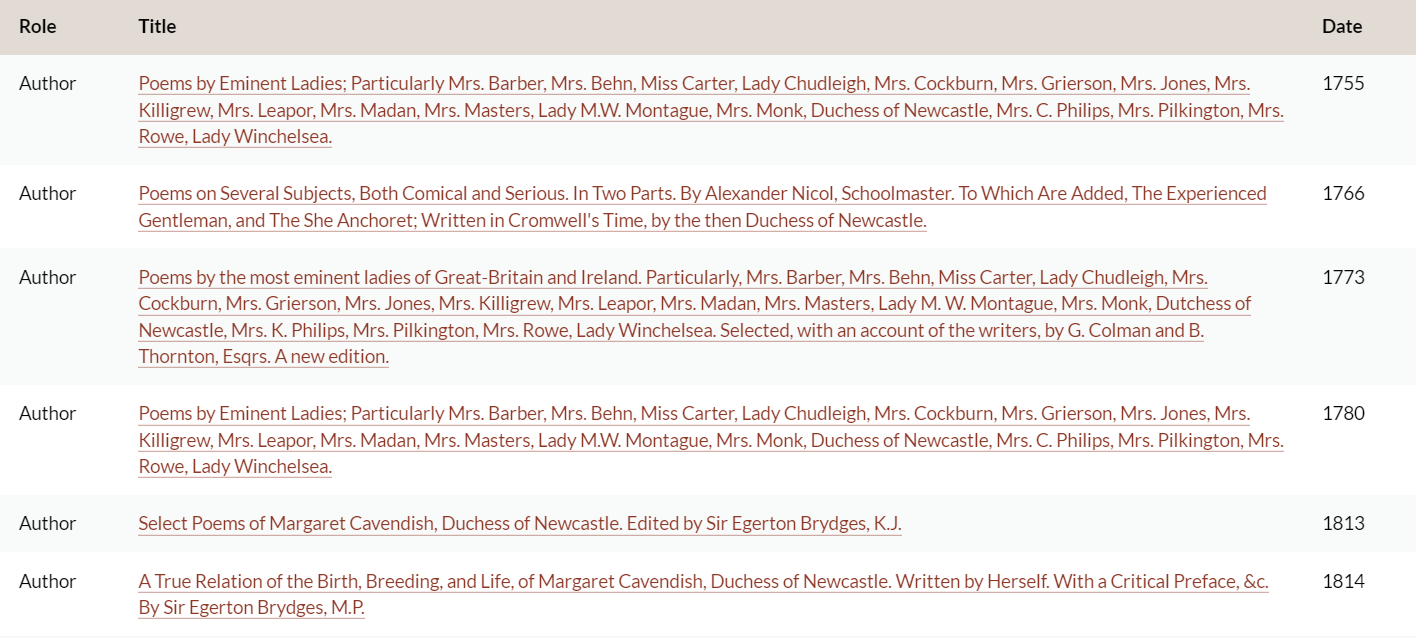

We now recognize Cavendish as an illustrious literary and philosophical figure, but it was not until the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that her writing began to receive scholarly attention and unabridged republication. Four of Cavendish’s six titles in the WPHP (including three editions of one anthology) contain short excerpts of Cavendish’s work, included among the works of other authors, while the remaining two publications feature Cavendish alone, and subject to the commentary of a belittling editor.

Figure 2. A table of Margaret Cavendish’s six titles in the WPHP.

Poems by Eminent Ladies (1755, 1773, and 1780), an anthology of women poets from the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, features seven of Cavendish’s poems from Poems, and Fancies. In comparison to other included authors, such as Aphra Behn, Mary Leapor, and Laetitia Pilkington, Cavendish’s section of featured poetry is minimal. Within this anthology, the titles of some of Cavendish’s included poems have been changed (for example, Cavendish’s “A Dialogue Between Melancholy and Mirth” becomes “Mirth and Melancholy”) and in the case of the poem “Wit,” the editors appended part of a different poem to the last stanza of Cavendish’s originally titled “The Mine of Wit,” without separation or note. By shortening “The Mine of Wit,” the editors omit Cavendish’s discussion of the qualities of metals, continuing the posthumous exclusion of her philosophical writing. In their preface, the editors of the 1773 edition, G. Colman and B. Thornton, defend their selection, stating, “it was…thought better to omit those pieces, which too plainly betrayed the want of learning, than to insert them merely to disgrace [the author’s other poetry],” but do not admit to altering the works of their compiled writers (iv). Though the editors include Cavendish in their list of “Eminent Ladies,” the nominal focus on her work, their description of her verse as “uncommon” and in need of cultivation, and their concealed modification of her poetry suggest they were not fully exempt from the critical eighteenth century view of Cavendish (198).

Samuel Egerton Brydges was the editor of the only two publications of Cavendish’s work that focus solely on her: Select Poems of Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle. Edited by Sir Egerton Brydges, K.J. (1813) and A True Relation of the Birth, Breeding, and Life, of Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle. Written by Herself. With a Critical Preface, &c. By Sir Egerton Brydges, M.P. (1814). In the prefatory material to Select Poems, Brydges admits these titles were published “partly by accident” and critiques Cavendish’s poetic diction, style, and overall intelligence (i). Select Poems—which Brydges calls “an early and brief exhibition of the productions of a private press [The Press of Lee Priory], which may hereafter, I trust, bring forth far more important works” (emphasis added)—is a compilation of Cavendish’s poetry taken primarily from Poems, and Fancies, with small selections pulled from Poems, or, Several fancies in verse with the Animal parliament in prose (1668), and from “The Convent of Pleasure” [published in Plays, Never Before Printed (1668)] (i). In particular, Cavendish’s Poems, and Fancies and her play, “The Convent of Pleasure,” highlight her philosophical and proto-feminist perspectives; however, Brydges’s compilation excludes Cavendish’s overtly philosophical poetry and features her less emblematic poems on emotion and nature, presenting her as a more romantic, and less radical, author.

Liza Blake’s digital critical edition of Cavendish’s Poems, and Fancies (which compiles the 1653, 1664, and 1668 editions into a free and accessible resource) confronts the historic misrepresentation of Cavendish’s first publication. Blake echoes Tamara Tubb’s focus on the importance of context to reading Cavendish’s work. She notes that Poems, and Fancies possesses an interconnected structure, featuring multiple “Clasp” sections meant to guide the reader to and between sections, and that Cavendish “did not write individual poems to be read in isolation” [“Reading Poems (and Fancies)”]. The long eighteenth century publications of Cavendish’s poetry as fragments, unmoored from their surrounding text, suppressed her writing on subjects dominated by male authors, such as natural and moral philosophy. Poems by Eminent Ladies and Brydges’s Select Poems misrepresent Cavendish as they assert that their small, disordered selections from Poems, and Fancies act as a sufficient blueprint of Cavendish’s poetic corpus.

Samuel Egerton Brydges and the Press of Lee Priory

As the only contributor and firm to publish a volume of Cavendish’s work (without any other included authors) between 1700 and 1836, Samuel Egerton Brydges and the Private Press of Lee Priory merit further investigation. Brydges, an author and editor who lived at the Lee Priory estate with his son, is an interesting historical and literary figure (Goodsall, “Lee Priory and the Brydges Circle”). In the “Advertisement” for Select Poems, Brydges claims to be a descendant of William Cavendish and his first wife, Elizabeth Basset (ii). Brydges writes, “The Editor of these Poems is proud to record his descent” from the great-granddaughter of the Duke of Cavendish, Lady Elizabeth Egerton (ii). Brydges provides no clear motive for adopting Cavendish’s poetry as the first and third publications of the Press of Lee Priory; his supposed genealogical connection to the Duke may be the most plausible reason. However, Brydges does not supplement his claim of relation with any proof. Robert H. Goodsall, author of “Lee Priory and the Brydges Circle,” writes of a controversial case brought to the Committee of Privileges of the House of Lords by Brydges in 1789, which makes his claim to the Newcastle line appear increasingly questionable. Brydges declared himself a descendent of John Brydges, the Baron of Chandos, but had little proof to reinforce his claim to the House of Lords (Goodsall 6). In 1803, after fourteen years of petitioning for the right to the Chandos barony, it was ruled that Brydges was “descended from an obscure yeoman family of Harbledown, near Canterbury, of the name of Bridges,” and had no relation to the late Baron (Goodsall 6). It was also proposed that Brydges falsified documents presented in the case, but he faced no charges for this offense. The historical context of Brydges’s potential forgery and unsubstantiated claims to the Chandos barony divests credibility from his purported connection to William Cavendish, though there is not enough evidence against his claim to disprove it entirely.

Figure 3. John Dixon. Lee Priory, Kent. 1785. Wikimedia Commons.

The Private Press of Lee Priory operated out of the Brydges family estate between 1813 and 1822 (Goodsall 3). Run by John Johnson and John Warwick, “a compositor and a press man” respectively, the firm was plagued by ongoing deficits and financial issues (Goodsall 3). As their primary financier and editor, Brydges was intimately involved with each stage of the firm’s productions. In his 1834 autobiography, Brydges describes the early publications of the Press of Lee Priory, including Select Poems and A True Relation, as “rare tracts” he believed to be “of some use to our old English Literature” (The Autobiography, Times, Opinions, and Contemporaries of Sir Egerton Brydges 192). The motive behind Brydges’s choice to edit and twice republish Cavendish remains otherwise unspecified in his biography, but as a fellow author who privately printed his work for purposes beyond profit, connections can be drawn between Brydges and Cavendish.

The “Noble Critic” and the “[Un]true” Poet

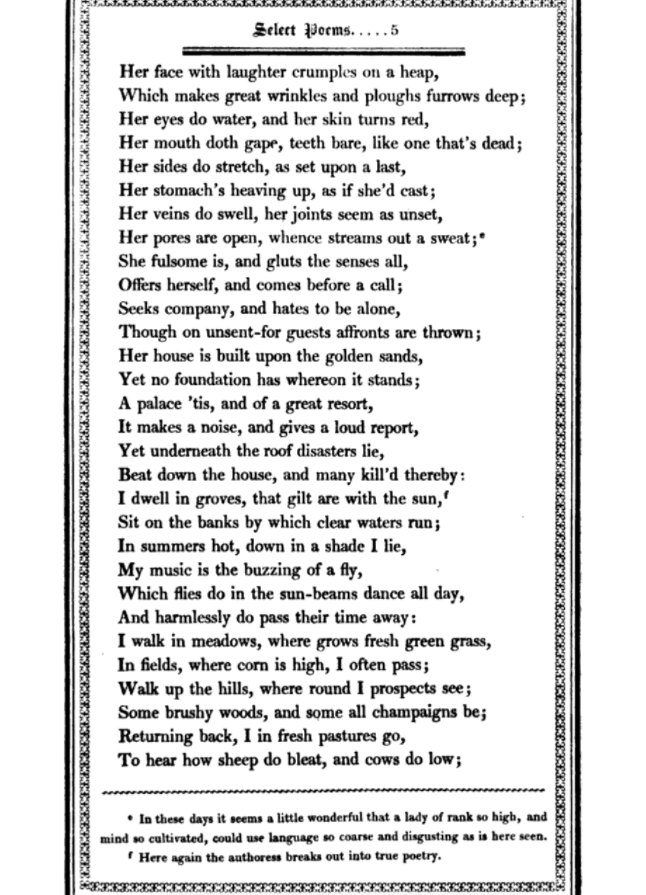

Figure 4. An example of Brydges critical footnotes in “A Dialogue Between Melancholy and Mirth.” Margaret Cavendish, edited by Egerton Brydges. 1813. Google Books, p. 5.

Brydges’s critique of Cavendish’s writing is ubiquitous and often contradictory throughout the paratexts of his publications, as found in the advertisements, prefaces, and footnotes of Select Poems and A True Relation of the Birth, Breeding, and Life, of Margaret Cavendish. In figure 4, Brydges takes issue with Cavendish’s “disgusting” language in and around the line, “Her pores are open, whence streams out a sweat” (Select Poems 5). His distaste for her verses on perspiration contrasts with his enjoyment of her lines on nature, a more conventional poetic subject that Brydges appeared to consider feminine and appropriate for Cavendish. Other complaints, such as “[Cavendish’s] taste appears to have been not only uncultivated, but perhaps originally defective,” and his admission that he was “frequently shocked by expressions and images of extraordinary coarseness; and more extraordinary as flowing from a female of high rank,” suggest Brydges’s conception of good writing lay in an author’s ability to conform to the demand for “fine words,” something that Cavendish vehemently decries in “Wherein Poetry Chiefly Consists” (ii, 13). As Brydges disparages her use of "prosaic and inelegant" language and suggests that only a minority of her work can be given the title of "true poetry," he fails to recognize that Cavendish sought to disrupt the assumed connection between "fine" language and true wit: for as she writes, “Words are but shadows, substance they have none” and it is “Fancy the form is, flesh [and] blood” (2, 5, “Wherein Poetry Chiefly Consists” 13). In both publications of her work, Brydges does not sincerely compliment Cavendish for her skills as a writer without offering a related complaint. Conversely, he is quick to praise Cavendish for the gendered role she fulfilled as “the faithful and endearing companion of all that virtuous nobleman’s [William Cavendish’s] subsequent troubles and exile,” and acknowledges the feminine domestic “charm” of her biographical writing (Select Poems i; A True Relation 3).

Brydges viewed himself as a “noble critic,” and advised his readers that “we must not compare [Cavendish’s] compositions with the more refined exactness of later times” (A True Relation 1, 9). By including his negative assessments in his analysis of Cavendish’s style, and republishing only a small and early selection of her formidable body of work, Brydges destabilized his own attempts at editorial nobility. Cavendish’s legacy in the long eighteenth century is represented by her six instances of excerpt-based republication, all of which omit her focus on philosophy, her subversion of gender norms, and her authorial persona, which she crafted for her readers in her prefaces and “Clasps.” As contemporary scholarship continues to reclaim Margaret Cavendish and honor her contributions to early modern science and literature, current scholars take Brydges’s advice, advice that he unevenly applied to himself: that Cavendish’s work must be understood in its historical and social contexts, and not judged by the supposedly “refined” standards of later centuries.

WPHP Records Referenced

Cavendish, Margaret (person, author)

Egerton Brydges, Samuel (person, editor)

John Johnson and John Warwick [The Private Press of Lee Priory] (firm, printer)

Colman, George (the elder) (person, editor)

Thornton, Bonnell (person, editor)

Behn, Aphra (person, author)

Leapor, Mary (person, author)

Pilkington, Laetitia (person, author)

Select Poems of Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle. Edited by Sir Egerton Brydges, K.J. (title)

Works Cited

Blake, Liza, et al. “The Complete Works of Margaret Cavendish.” Digital Cavendish: A Scholarly Collaborative, digitalcavendish.org/complete-works/.

Blake, Liza. “Reading Poems (and Fancies): An Introduction to Margaret Cavendish’s Poems and Fancies.” Margaret Cavendish's Poems and Fancies: A Digital Critical Edition, library2.utm.utoronto.ca/poemsandfancies/introduction-to-cavendishs-poems-and-fancies/.

Brydges, Egerton. The Autobiography, Times, Opinions, and Contemporaries of Sir Egerton Brydges, Bart. Vol. II, Cochrane and M'Crone, 1834.

Cavendish, Margaret, and Samuel Egerton Brydges. A True Relation of the Birth, Breeding, and Life, of Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle. Written by Herself. With a Critical Preface, &c. By Sir Egerton Brydges, M.P. Printed at the private Press of Lee Priory, 1814.

Cavendish, Margaret, and Samuel Egerton Brydges. Select Poems of Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle. Edited by Sir Egerton Brydges, K.J. Printed at the Private Press of Lee Priory, 1813.

Cavendish, Margaret. The Description of a New World, Called the Blazing World Written by the Thrice Noble, Illustrious, and Excellent Princesse, the Duchess of Newcastle. J. Martin, 1655.

Cavendish, Margaret. The Philosophical and Physical Opinions Written by Her Excellency the Lady Marchionesse of Newcastle. London, 1800.

Goodsall, Robert H. “Lee Priory and the Brydges Circle.” Archaeologia Cantiana, vol. 77, 1962, pp. 1–26, www.kentarchaeology.org.uk/Research/Pub/ArchCant/Vol.077%20-%201962/ 077-01.pdf.

Grierson, Constantia, et al. Poems by the most eminent ladies of Great-Britain and Ireland. Particularly, Mrs. Barber, Mrs. Behn, Miss Carter, Lady Chudleigh, Mrs. Cockburn, Mrs. Grierson, Mrs. Jones, Mrs. Killigrew, Mrs. Leapor, Mrs. Madan, Mrs. Masters, Lady M. W. Montague, Mrs. Monk, Dutchess of Newcastle, Mrs. K. Philips, Mrs. Pilkington, Mrs. Rowe, Lady Winchelsea. Selected, with an account of the writers, by G. Colman and B. Thornton, Esqrs. A new edition. Thomas Becket, 1773.

“Margaret Cavendish.” The Broadview Anthology of British Literature. Volume III: The Restoration and the Eighteenth Century. 2nd ed., edited by Joseph Black et al, Broadview, 2012, pp. 1–2.

Tubb, Tamara. “Print and perception: The literary careers of Margaret Cavendish and Katherine Philips.” British Library: Discovering Literature: Restoration & 18th century, 2018, www.bl.uk/restoration-18th-century-literature/articles/print-and-perception-the-literary-careers-of-margaret-cavendish-and-katherine-philips.

Woolf, Virginia. A Room of One’s Own. 1929. Renard, 2020.