This post is part of our Women & Philosophy Spotlight Series, which will run through March 2022. Spotlights in this series focus on women philosophers in the database.

Authored by: Angela Wachowich

Edited by: Michelle Levy and Kate Moffatt

Submitted on: 03/04/2022

Citation: Wachowich, Angela. "Women & Philosophy Spotlight Series." The Women's Print History Project, 4 Mar 2022, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/99.

Figure 1. Angelica Kauffman. Woman Reading. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Figure 1. Angelica Kauffman. Woman Reading. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

In 2021, the Journal of the History of Ideas published 31 total articles, 18 of which named male thinkers in the titles and none of which named a single female philosopher (Dr. Megan Gallagher, tweet). The discipline of philosophy continues to have a lower percentage of female graduate students and faculty than any other humanities or social science, and it barely outranks notoriously inequitable fields like computer science and physics (Andrew Janiak, Washington Post). As a feminist project committed to uncovering eighteenth- and nineteenth-century women’s knowledge production, this Spring, in celebration of Women’s History Month, The Women’s Print History Project is delighted to join ongoing conversations about the history of philosophy with our Women & Philosophy Spotlight Series. Between March 4 and April 1, 2022, we will be highlighting five of the many inspiring female thinkers featured on our database. As a bibliographical database that seeks to capture as much as we can of women’s contributions to print, the WPHP does not limit itself to a single genre or topic, and hence is ideally suited to capture the widest range of women’s intellectual history during the period. This attention to women thinkers in print during the long eighteenth century will, we hope, contribute to this recovery work and to the ongoing efforts to broaden and change what counts as philosophical discourse.

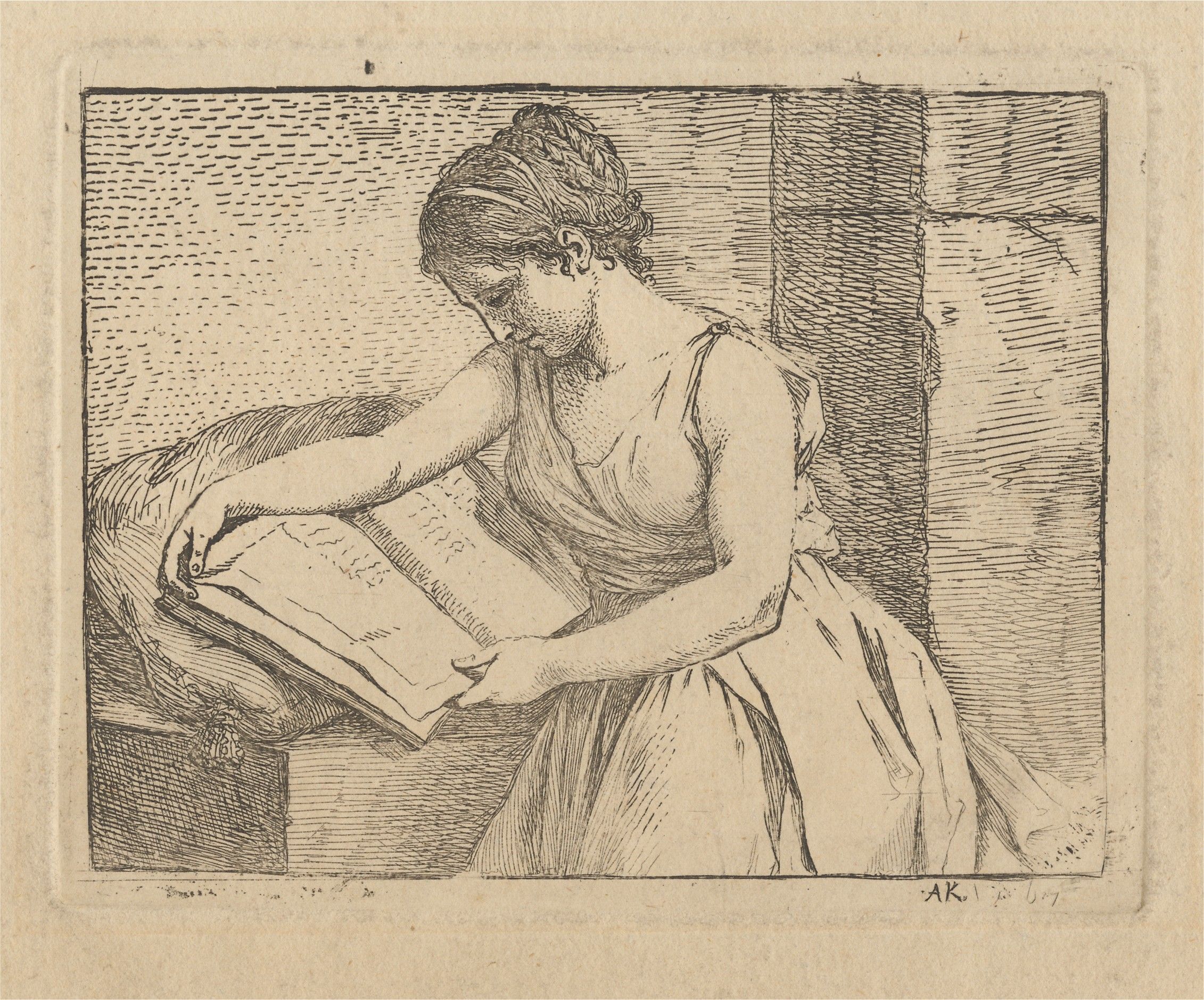

Figure 2. William Blake, Etching from Mary Wollstonecraft's Original Stories from Real Life, 1801. Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 2. William Blake, Etching from Mary Wollstonecraft's Original Stories from Real Life, 1801. Wikimedia Commons.

It helps to begin by asking, what role could women play in eighteenth-century philosophy when most were denied formal schooling and all were denied university educations? While female philosophers were constrained to private education, many “daughters of educated men,” as Virginia Woolf describes educated women of the period (and we would hasten to add wives and sisters and mothers of educated men) undertook comprehensive study, circulating their ideas in manuscript and print. As Woolf’s remark suggests, most female thinkers were born to upper-middle-class families with the resources to foster their daughters’ intellectual curiosity, though this was not necessarily the case, as we see in our final spotlight in the series. Even with these usual limits, there is a breadth and depth of women’s thinking that has yet to be addressed.

Unfettered by the formal limitations of academic discourse, women’s philosophical writing took a variety of forms, including treatises and histories as well as novels and poems, and topically ranged across many subjects, from education, to political theory, to natural history, to early feminist thought. This month’s WPHP Monthly Mercury episode will feature Lisa Shapiro and her Bibliography of Works by Women Philosophers of the Past, which is attempting to account for women's philosophical writing beyond philosophy's "Big Seven"; our Spotlights, similarly, deliberately take up lesser and even wholly unknown figures to diversify our understanding of the discipline and celebrate women who are never contemplated as part of the philosophical canon.

The Spotlight Series launches today, March 4, with “(Unidentified) Woman not Inferior to Man: ‘Sophia,’ Proto-Feminism, and the Anonymous Female Writer.” In this Spotlight, Angela Wachowich considers the pseudonymous proto-feminism of “Sophia, a Person of Quality,” and the implications of recovering unidentifiable female authors.

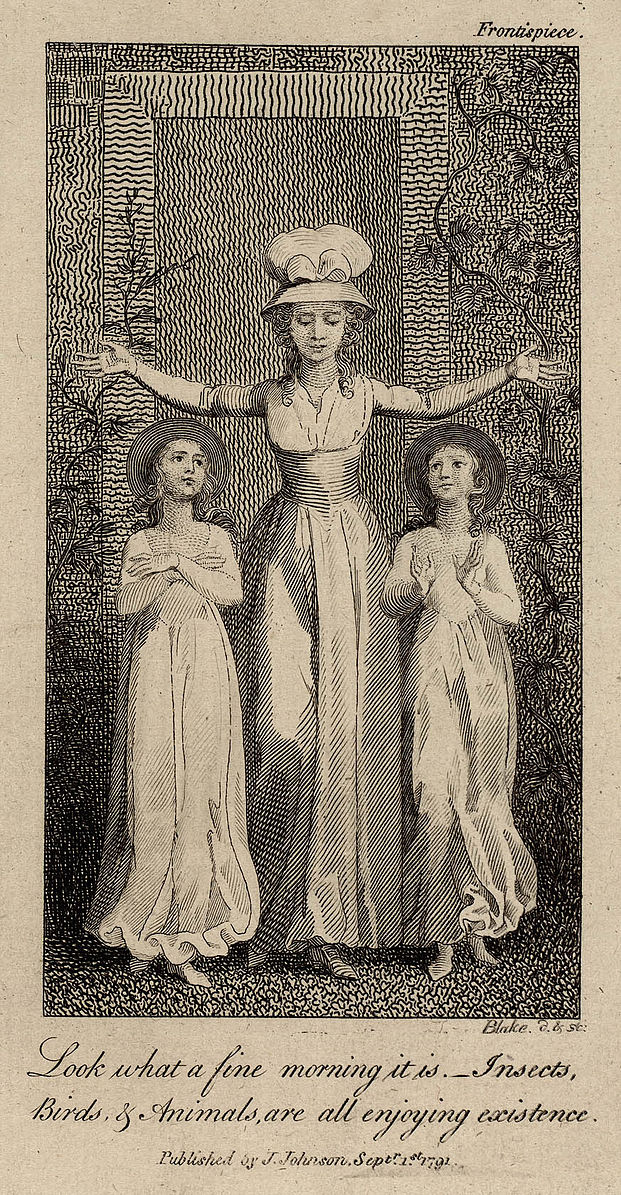

Figure 3. Margaret Cavendish by Abraham van Diepenbeeck. The frontispiece of Natures Pictures, 1671. British Library.

On March 11, in "Reprinting Margaret Cavendish," Belle Eist considers how Margaret Cavendish, though now regarded as one of the more important scientific and proto-feminist thinkers of the seventeenth century, was mostly forgotten during the long eighteenth century. The very few selections of her writing that were reprinted were characterized by distortions and dismissals that reflect the long history of forgetting and censuring female thinkers.

On March 18, Isabelle Burrows takes us through Harriet Martineau’s Illustrations of Political Economy in her Spotlight, "A Great Conviction: Metaphysical Solutions for Practical Issues in Harriet Martineau's 'Illustrations of Political Economy,'" which explores the relationship between the material elements of her publications and the philosophical aims of the books. By examining Martineau’s textual strategies for popularizing Adam Smith and Thomas Malthus’s theories of political economy, Isabelle discusses how the dual function of each Illustration as periodical instalment and standalone publication allowed Martineau to intervene in contemporary political debates and address existential concerns brought on by the rapid pace of industrialization in nineteenth-century Britain.

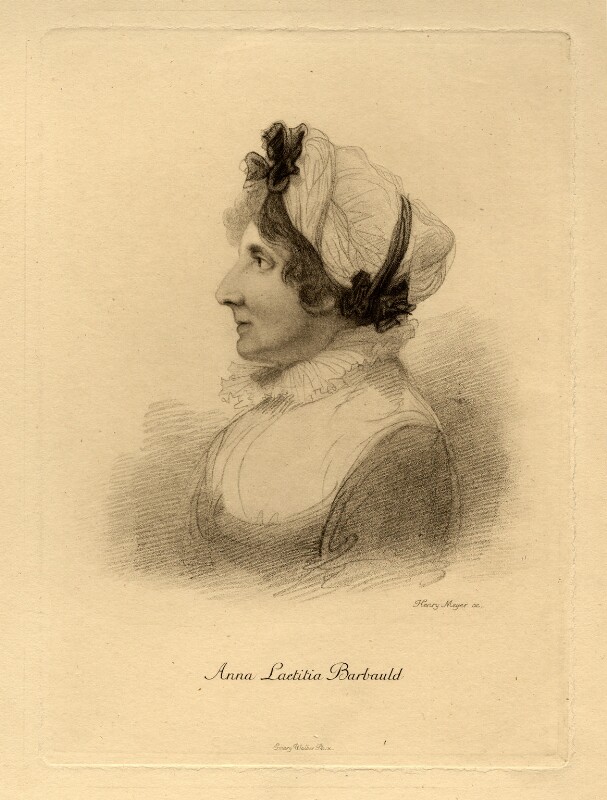

Figure 4. Anna Letitia Barbauld (née Aikin) by Sir Emery Walker, after Henry Meyer. c. 1907. National Portrait Gallery.

On April 1, Michelle Levy, Kate Moffatt, and Tamanna T. think about Anna Letitia Barbauld, aptly named by her biographer William McCarthy as the “Voice of the Enlightenment,” in their Spotlight, "Anna Letitia Barbauld's Writing and the Problem of Genre." This spotlight focuses on the generic diversity of Barbauld’s career, engaging with how we determine and analyze genre in the WPHP, as well as acknowledging how her philosophical interventions erupt everywhere in her writing—in her poems, her writing for children, her educational theory, her literary criticism, as well as her explicitly political essays. Even her Hymns in Prose for Children, a liturgy she wrote for boys at her school, is a philosophical text, engaging in theories of childhood development, cognition, theology, even cosmology.

Our Spotlight Series ends on April 8 with "Ann Williams: Postmistress, Poetess, and Sericulturist." This Spotlight returns us to the obscurity of so many women philosophers, focusing on Ann Williams and her 1773, self-published, Original poems and Imitations, by Michelle Levy. Only recently brought to the attention of the WPHP by a tweet from John Overholt, Curator of Early Books & Manuscripts, Houghton Library, Harvard University, and with the aid of research on the volume and Williams by the bookseller, Carpe Librum, this spotlight investigates this volume of poems by the unknown “A. Williams, Post-mistress of Gravesend,” as she signed herself on the dedication page. If Williams was a postmistress by day, by night she was a scientist who engaged in astronomy, botany, chemistry, entomology—indeed she died during an experiment gone horribly wrong—and, somehow, she also found time to write verse. This final spotlight reflects on the myriad written forms within which women participated in the history of thought, and the varieties of experience they contemplated.

Works Cited

Anderson, Nick, Andrew Janiak and Christia Mercer. “Philosophy’s gender bias: For too long, scholars say, women have been ignored.” The Washington Post, 28 April, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/grade-point/wp/2015/04/28/philosophys-gender-bias-for-too-long-scholars-say-women-have-been-ignored/.

Gallagher, Megan [twasmegan]. “Two fun facts! In 2021, the Journal of the History of Ideas published articles namedropping a total of 18 male thinkers in the titles and zero women. Also in 2021, the History of Political Thought published articles naming a total of 27 men in the titles and zero women.” Twitter, 24 February 2022, https://twitter.com/twasmegan/status/1497018587004944391?s=11.

Woolf, Virginia. Three Guineas. Blackwell Publishing, https://www.blackwellpublishing.com/content/bpl_images/content_store/sample_chapter/9780631177241/woolf.pdf.