This post is part of our Women & Philosophy Spotlight Series which will run through March 2022. Spotlights in this series focus on women philosophers in the database.

Authored by: Michelle Levy

Edited by: Kate Moffatt and Kandice Sharren

Submitted on: 04/02/2022

Citation: Levy, Michelle. “Ann Williams: Postmistress, Poetess, Sericulturist.” The Women's Print History Project, 2 April 2022, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/106.

Figure 1. Maria Sibylla Merian, “Maulbeerbaum samt Frucht,” Der Raupen (The Caterpillars), 1679, Plate 1. It depicts the fruit and leaves of the mulberry tree and the eggs and larvae of the silkworm moth. Wikipedia.

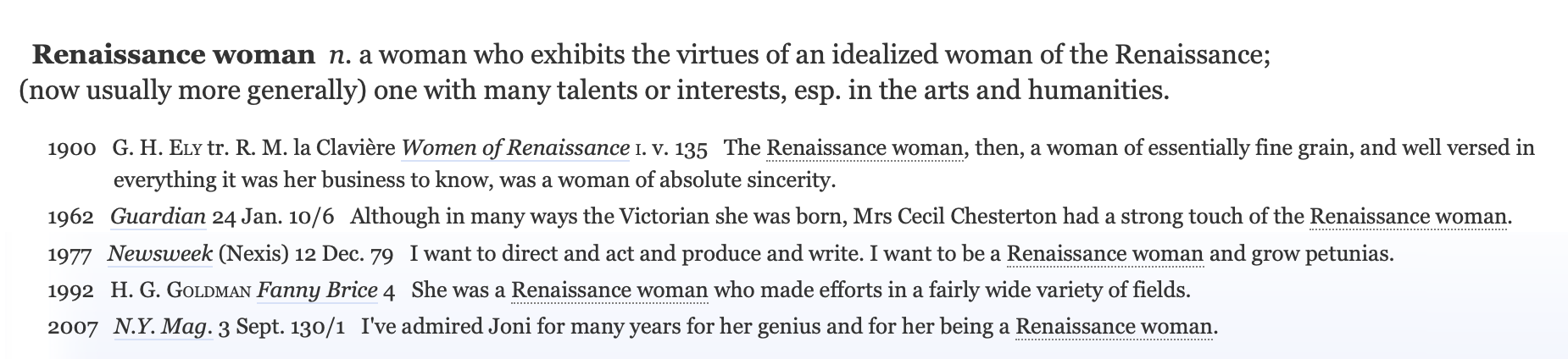

There is no female or gender-neutral equivalent for the concept of “Renaissance man,” a term that originates in the Italian phrase, Uomo Universale, or “Universal Man.” According to the OED, it is “a man who exhibits the virtues of an idealized man of the Renaissance; (now usually more generally) one with many talents or interests, esp. in the arts and humanities.” Although the term has been applied beyond the Renaissance, Wikipedia continues to provide only men as examples. The OED more helpfully includes an entry for “Renaissance woman,” but the attestations it includes suggest some of the challenges involved in any straightforward translation of the term from men to women. The first and earliest quotation, from 1900, presents a more gendered understanding of what a “Renaissance woman” might be: she is a woman of “essentially fine grain,” whatever that means; she is “well versed in everything it was her business to know,” a statement that implies that there are limits on what she should know; and she is a woman “of absolute sincerity,” a quality nowhere associated with the Renaissance man. The other attestations, beginning the 1960s, hew more closely to the traditional understanding, but even here the concept appears somewhat tempered: again, few so-called Renaissance men are tepidly described as having “made efforts in a fairly wide variety of fields.”

Figure 2. OED entry for “Renaissance woman.”

It seems obvious that something critical has been lost in translation. This is not because no women fit the masculine definition; far from it. But as Lisa Shapiro discussed in our Women and Philosophy podcast episode (Season 2, Episode 10), we know so little about women who excelled in philosophical discourse, the “queen of the disciplines,” let alone women with achievements in a range of intellectual fields and endeavors. Indeed it seems likely that in the period the WPHP covers, women, more so than men, would almost out of necessity develop knowledge in a variety of fields. Ann Williams, the subject of this person spotlight and a woman who is almost entirely unknown today, epitomized a "Donna Universale." Mary Wollstonecraft, in the Vindication of the Rights of Woman, lamented that women were deliberately prevented from going into any one branch of knowledge too deeply:

… the little knowledge which women of strong minds attain, is, from various circumstances, of a more desultory kind than the knowledge of men, and it is acquired more by sheer observations on real life, than from comparing what has been individually observed with the results of experience generalized by speculation. Led by their dependent situation and domestic employments more into society, what they learn is rather by snatches; and as learning is with them, in general, only a secondary thing, they do not pursue any one branch with that persevering ardour necessary to give vigour to the faculties, and clearness to the judgment. (1792, 40–41)

Anna Barbauld, the subject of the previous spotlight, felt this exclusion keenly. In an unpublished poem to addressed to her brother, “To Dr Aikin on his Complaining that she neglected him, October 20th 1768,” she observes how “like two scions on one stem we grew, / And how from the same lips one precept drew,” until she was forcibly separated from her brother, when he was allowed to leave to pursue medical studies, and she was forced to remain home. She laments that whereas once “the same studies saw us both pursue; / Our path divides.” She questions this separation, saying that brother and sister were not “stampt with separate sentiments and taste." She then tells herself,

But hush my heart! nor strive to soar too high,

Nor for the tree of knowledge vainly sigh;

Check the fond love of science and of fame,

A bright, but ah! a too devouring flame.

Content remain within thy bounded sphere,

For fancy blooms, the virtues flourish there.

Of course, as the previous spotlight discusses, Barbauld did reach for “the tree of knowledge,” though she was checked when she attempted to escape women’s “bounded sphere.” Indeed, Barbauld is a perfect example of the heights that a woman could ascend through the breadth and depth of her learning, but also of the dangers that a woman confronted in attempting to transcend what it was “her business to know.”

Ann Williams was a woman who did not “check the fond love of science” and arts and instead pursued multiple lines of intellectual and creative endeavour. The WPHP can provide only an incomplete view of her career, because most of her contributions were made in scientific journals. There is only one publication of hers included in WPHP, Original Poems and Imitations, which was printed for the author in 1773. This, moreover, is a recent addition to our title records, only recently brought to the attention of the WPHP by a tweet from John Overholt, Curator of Early Books & Manuscripts, Houghton Library, Harvard University, who cites research on the volume and Williams by the bookseller, Carpe Librum. This title was likely previously missed by us (and other sources) because on the title page the author is given as “A. Williams”; it is only on the dedication page that she is identified as “Post-mistress of Gravesend,” that is, as a woman.

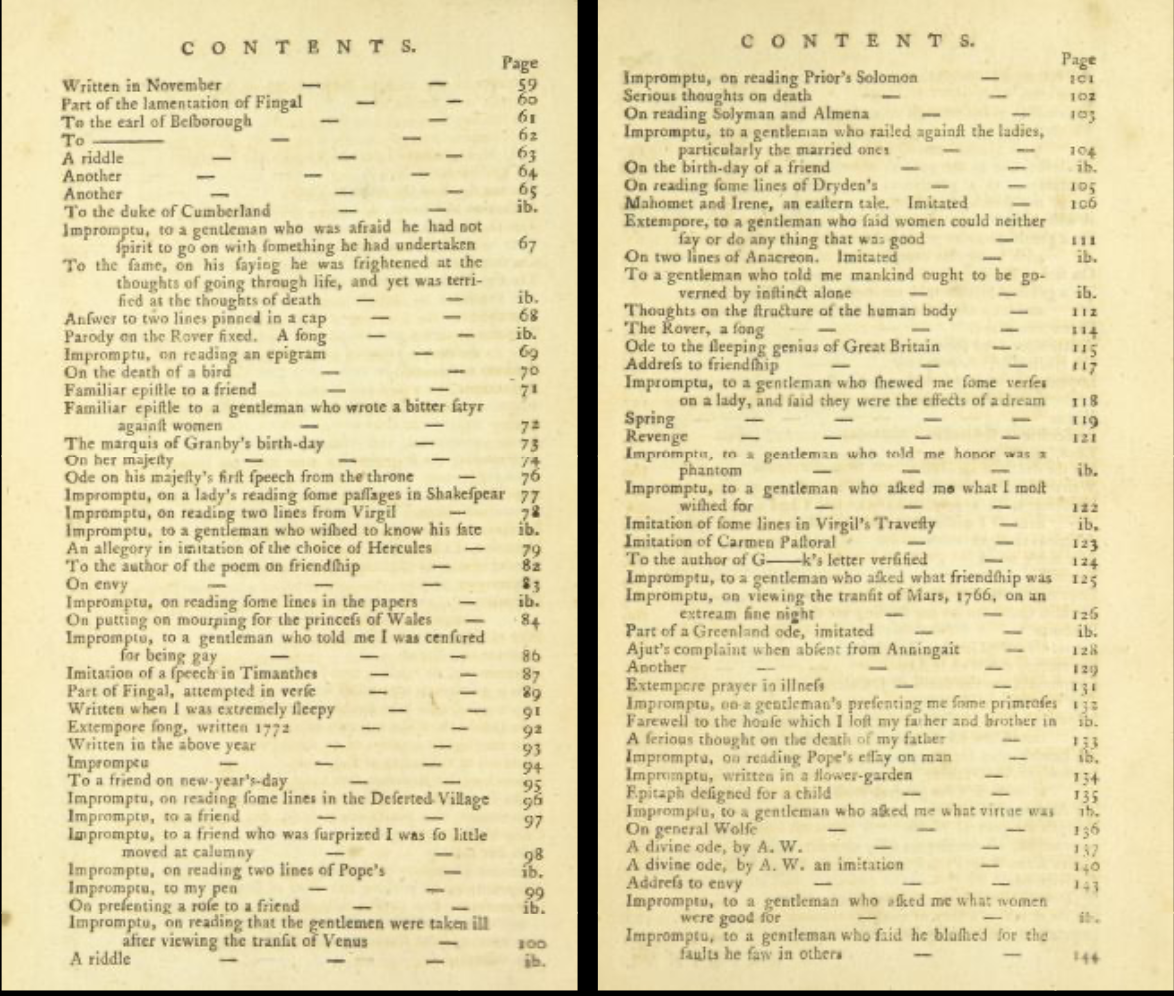

As may be seen on the second and third page of the Table of Contents, most of the poems are very short, taking the form of either imitations of classical and other verse, or “Impromptus,” poems that claim to be composed in the moment. As a postmistress by day, Williams had limited time to write her poems; as we learn from the poems themselves, she had to compose in short bursts, such that many of her poems are occasional in nature or inspired by reading or experiences. Several of her poems hint at the challenges in being a postmistress by day, poet by night, such as one entitled, “Written when I was extremely sleepy, yet obliged to attend business” (91) and “Impromptu, to my Pen,” which beings: “Adieu my pen, dull sleep has seiz’d my head / I now must leave thee, and must go to bed” (99). In “Impromptu, to a gentleman who asked me how I spent my evenings without playing cards,” we seem to be presented with a description of how Williams found the time to write poems: “The bus’ness of the day being full o’er, / I fly from care to the poetic lore” (149).

Figure 3. Table of Contents, Ann Williams, Original Poems and Imitations. British Library.

Williams’s poems address a range of commonplace topics, and many are entirely typical of the poetry of the day, addressing both personal and public topics, from the death of her father and brother to that of General Wolfe. Other poems speak more directly to her interest in scientific endeavors and her views on the position of the sexes. In the following excerpt from her poem, “On reading some lines in praise of Mrs Macauly,” Williams attests to the influence of Catharine Macaulay, particularly in her claim that women look to history to better and improve themselves. In this poem, written to one “Brent,” Williams combines her proto-feminism with her devotion to women’s pursuit of “ev’ry art and science”:

Wou’d all the sex encourage us like you,

More real merit in us soon you’d view;

By you protected, females soon wou’d soar,

And ev’ry art and science wou’d explore.

This I with truth aver, the more we know,

The greater happiness we can bestow;

For in your search thro life, you’ll surely find,

No joy from an uncultivated mind. (58)

A more playful and satiric voice emerges in the short poem, “Extempore, to a Gentleman who said women could neither say or do any thing that was good”:

If nothing good we say,

Or nothing good we do,

How comes it then, I pray,

We model such fine things as you?

For this I will maintain,

And hope it is no treason,

You’d savages remain,

Did we not teach you reason. (111)

A string of other poems establish Williams’s rejection of patriarchy in a way that anticipates writers like Barbauld and Wollstonecraft. In the last poem in the volume, “Impromptu, On Reading Mrs Rowe’s Poems” (190–91), she offers Elizabeth Singer Rowe as her true inspiration and dedicatee (the volume itself is formally dedicated to the first and second PostMaster General, H.F. Thynne and Francis, Baron Le Despencer). In “Address to the Ladies of England” (45), in terms strikingly similar to Wollstonecraft, she laments that

Too long, alas! Too long, ye British fair,

Has dress and nonsense been your only care;

To reason deaf, and to conviction blind,

You’ve lost the chain by which you led mankind.

She laments the frivolity of women’s lives—“Cards, routs, coteries, op’ras, balls and shews, / The only bus’ness of your lives compose”—and reminds them of the fleetingness of youth and beauty. She urges women:

For shame: awake! The historic page explore,

Recount those heroes Rome and Athens bore,

With Greece and Sparta, and you there will find

A glorious pattern for all womankind.

In “Impromptu, on reading an essay on education” (178-9), a poem seemingly responding to Samuel Johnson’s An Essay on Education (1771), she lays bare the women’s degradation as patriarchy, arguing that men are responsible for fettering women’s “free-born minds.”

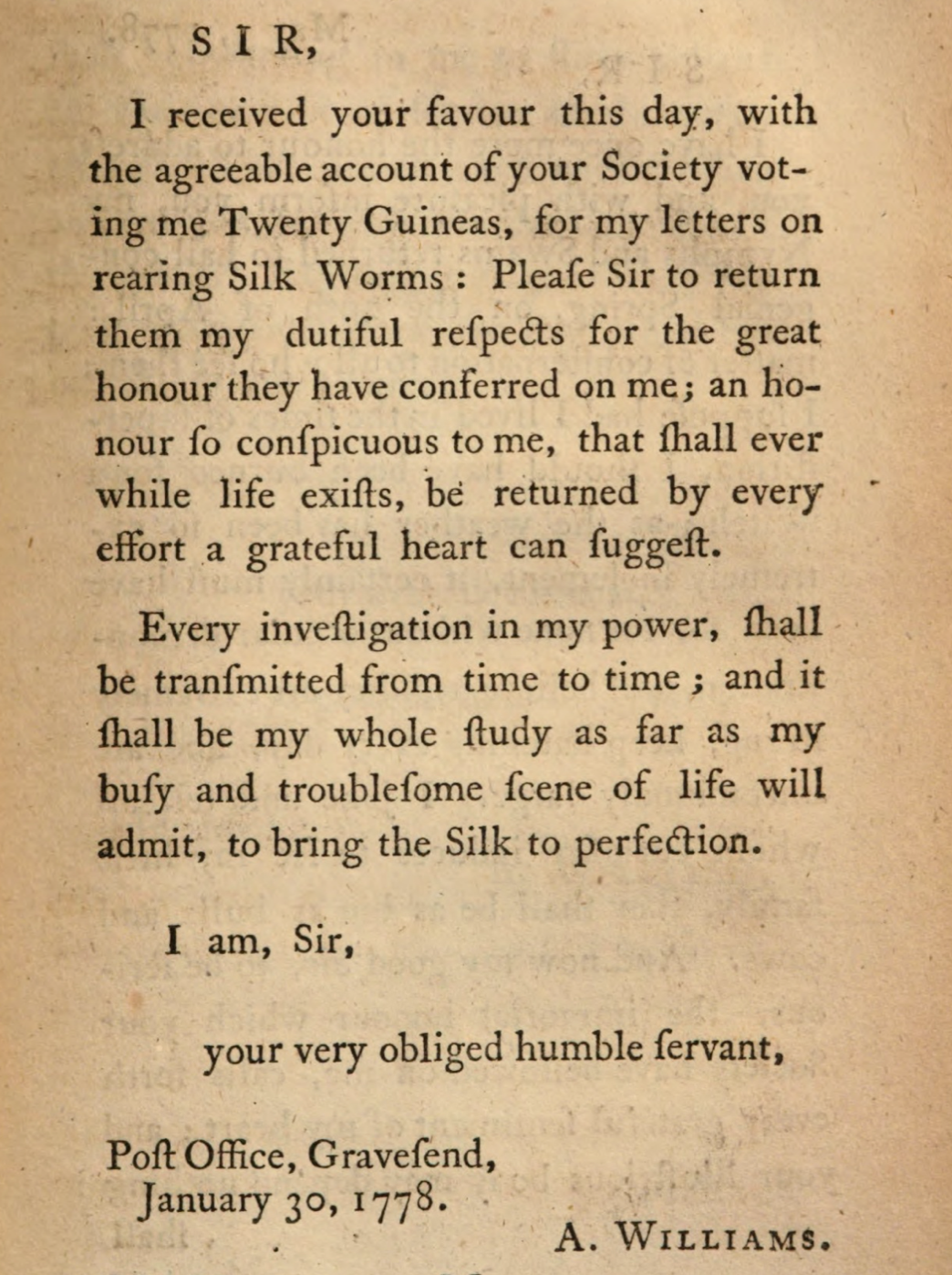

Poetry was not Williams’s only or even her main activity outside of her work as a postmistress. Several poems hint at her scientific pursuits: “Thoughts on the structure of the human body” (112), “Impromptu, on reading that all the gentlemen were taken ill the day after viewing the transit of venus” (100), and “Impromptu, on viewing the transit of Mars, 1766, on an extream fine night” (126). These poems and others demonstrate her interest in astronomy, botany, chemistry, and entomology, and in 1784, eleven years after her poems were published, evidence of Williams’s direct participation in scientific discourse appeared in print, when letters she had sent to the Society, Instituted at London, for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce, beginning in 1777, were published in the second volume of their Transactions; the following year, she was given twenty guineas for her researches. A letter published in Transactions, dated 30 January 1778, thanks the Society for this honour, and pledges that “it shall be my whole study as far as my busy and troublesome scene of life will admit, to bring the silk to Perfection.”

Figure 4. Royal Society of Arts, Transactions of the Society, vol. 2 (1784), 169. HathiTrust Digital Library.

The distribution of premiums to amateur scientists, celebrated in James Barry’s engraving of 1792, was of enormous importance to a working woman like Williams. Indeed, as Leonie Hannan has explained, it was one of a series of new opportunities that emerged for women’s participation in science in the eighteenth century:

Whilst women remained excluded from roles within the learned societies and universities of eighteenth-century Britain and Ireland, the century did offer other inroads to scientific enquiry and writing. Building on activity undertaken by largely aristocratic women of the 1600s in the fields of experimental science, medicine and technical writing, in the 1700s a more diverse range of women were engaging with science in public fora, whether that was through periodicals or poetry. (520)

Figure 5. James Barry, “The Distribution of Premiums in the Society of Arts,” 1792. Tate.

In our spotlight on Margaret Cavendish, we encountered evidence of elite women dabbling in experimental science; with the arrival of the Society, founded in 1754, a way of supporting amateur activities, we find more middling women like Williams being supported in their pursuit of scientific knowledge. In 1775 and 1776, Williams had written to the Society before about the potential use of the common woodland plant, cuckoo pint, in dyeing (Hannan 527n46), but her most significant engagement with the London Society was with sericulture, or the cultivation of silkworms. Throughout these letters, Williams describes in detail the efforts she made to find the worms appropriate food and housing, to clean and nurture them. She frequently refers to silkworms as “my little family,” seeks to comfort them and notes when they appear to be in pain or distress. Indeed, it is arguable that through her scientific investigations Williams practiced what feminist theorist Carol Gilligan subsequently termed an “ethics of care,” characterized by attentiveness, responsibility, competence, and responsiveness. Hannan notes that Williams prioritizes learning about and attending to the needs of her silkworms over their silk production, and even compares her concern for them to Barbauld’s “Mouse’s Petition,” though her poem “The Caterpillar” is perhaps a better expression of how attention to an individual creature creates the conditions for an ethics of care. In the poem, Barbauld reflects upon how even though she had “sworn perdition to thy race, / And recent from the slaughter am I come / Of tribes and embryo nations,” when confronted with

A single wretch, escaped the general doom,

Making me feel and clearly recognise

Thine individual existence, life,

And fellowship of sense with all that breathes,--

Present’st thyself before me, I relent,

And cannot hurt thy weakness.

According to Robert Pocock, in his 1797 history of Gravesend, Williams died while conducting an experiment: "She unfortunately lost her life, by accident, whilst employed in a chymical Process, which set fire to her cloaths and burnt her past recovery" (16).

Pocock does not provide a date, but according to Carpe Librum, “the burial of an Ann Williams is recorded at St. Peter & St. Paul parish church, Milton-next-Gravesend on 14 January 1779, a date which roughly harmonizes with her last communication to the Society of Arts on 14 May 1778.” This final spotlight celebrates Williams’s life as a philosopher who engaged in a wide variety of activities and written forms. Williams embodies the idea of philosophy as the “queen of the disciplines,” as Lisa Shapiro put it, as she engages in scientific observation and experimentation, reflection and thought about our place in the world both in her scientific discourse and in her poetry. As such, she joins the women we have discussed in this spotlight series, women who participated in the history of thought, and shaped that history through the varieties of experience they contemplated.

WPHP Records Referenced

Barbauld, Anna Letitia (person, author)

Johnson, Samuel (person, author)

Original poems and Imitations (title)

Poems (title)

Macaulay, Catharine (person, author)

Rowe, Elizabeth Singer (person, author)

Williams, Ann (person, author)

Wollstonecraft, Mary (person, author)

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects (title)

Works Cited

Carpe Librum. “Ann Williams: 18th century working woman, feminist poet, and scientific martyr.” Carpe Librum, https://www.carpelibrumbooks.com/ann-williams-gravesend-poems-1773-first-edition-feminist-poet-and-scientific-martyr.

Hannan, Leonie. “Experience and Experiment: The Domestic Cultivation of Silkworms in Eighteenth-Century Britain and Ireland." Cultural and Social History, vol. 15, no. 4, 2018, pp. 509–30.

Howes, Anton. Arts & minds: how the Royal Society of Arts changed a nation. Princeton UP, 2020.

“Renaissance, n.” OED Online, Oxford UP, March 2022, www.oed.com/view/Entry/162352.

Pocock, Robert. The history of the incorporated town and parishes of Gravesend and Milton, in the county of Kent; selected with accuracy from topographical writers, and enriched from manuscripts hitherto un-noticed. Recording every event that has occurred in the aforesaid town and parishes from the Norman conquest to the present time. Pocock, 1797.

Royal Society of Arts. Transactions of the Society, vol. 2, 1784, pp. 153–71.