This post is part of our Women & Philosophy Spotlight Series, which will run through March 2022. Spotlights in this series focus on women philosophers in the database.

Authored by: Isabelle Burrows

Edited by: Michelle Levy and Kandice Sharren

Submitted on: 03/17/2022

Citation: Burrows, Isabelle. "A Great Conviction: Metaphysical Solutions for Practical Issues in Harriet Martineau's 'Illustrations of Political Economy.'" The Women's Print History Project, 17 March 2022, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/102.

Figure 1. Title page of a nine-volume edition of Illustrations of Political Economy. HathiTrust Digital Library.

Of the ninety-four titles currently listed under Harriet Martineau’s name in the WPHP, over fifty seem to be variations on the same title: Illustrations of Political Economy. When I first began creating metadata for Martineau’s titles, I was confounded by the almost interminable list of Illustrations, which seemed to defy categorization by genre or print type. The WPHP data model is designed for stand-alone publications and for re-prints which are categorized as new editions, but we avoid periodicals, which tend to fall outside these parameters. Because of their monthly release, originally between 1832 and 1834, the Illustrations might be considered periodicals; however, each illustration is a self-contained fictional narrative, which makes them more like the discrete publications which our data model does include. Compounding the confusion were the multiple reprints of the Illustrations, which sometimes appeared in reissues alone and sometimes in nine-volume compilations composed of remaindered editions. This meant publications which might look like new editions were in fact collections of previously published material bound in a new format. To explain the dual nature of the Illustrations as a hybrid of periodical and book, I will examine the dual purpose the Illustrations served as responses to current events in politics and economics, and as philosophical texts attempting to address wider and more lasting anxieties brought on by the rapid pace of industrialization in nineteenth-century Britain.

Martineau described the creation of the Illustrations as “The strongest act of will that I ever committed myself to” (Autobiography 138) and while the gruelling pace at which she produced them did require great endurance, she was no stranger to such labours. Even in childhood Martineau was obsessed by metaphysical quandaries, and highly motivated to develop precision in her intellectual practice, despite the fact that “it was not thought proper for young ladies to study very conspicuously” (99). She studied languages and translation, the classics, and, most significantly for her later career, the treatises of Unitarian and Liberal theorists, which her brother James shared with her as he learned about them at college (105). Long before she made her 1823 print debut in the Unitarian periodical The Monthly Repository, Martineau’s opinions were being informed by thinkers like the Unitarian pioneer Joseph Priestley. His theory of Necessity became for Martineau the “great conviction which henceforth gave to my life what is has had of steadiness, consistency, and progressiveness" (104).

Figure 2. Richard Evans, Harriet Martineau, 1834. © National Portrait Gallery.

At its most basic, Necessarianism was a theory which identified God as the instigator of all action in the universe. According to Thomas Hobbes, a great influence on Priestley, “every desire, and inclination, proceedeth from some cause . . . in a continuall chaine . . . whose first link in the hand of God (Leviathan II: 148). Since all causes will have an effect, and since God is the original “cause” of creation, “no event could have been otherwise than it has been, is, or is to be . . . all things past present and to come, are precisely that the author of nature really intended them to be, and has made provision for” (Priestley 462). People have the liberty to think what they will, to choose to move their limbs, but since all actions, and all volitions of the mind, originate from the same chain of cause and effect which God first put in motion, human beings are ultimately doing what God intended for them to do. Like many thinkers of the nineteenth century, both Priestley and his disciple sought to solve practical issues with their metaphysical theories. Martineau saw the tenets of Necessarianism as explanatory of the conditions in which the working class lived. She suggests that Necessarianism is a solution to problems besetting the working class because it will bring them the comforting assurance that, if they understand that “no action fails to produce effects, and no effort can be lost,” workers can be assured of a product for their labours, and so “true Necessarians must be the most diligent and confident of all workers” (107). Free will, on the other hand, “leaves but scanty encouragement to exertion of any sort” (107). On a more practical level, Necessarianism was a gateway to a laissez-faire approach to the market and a hands-off strategy for aiding the working class: if God, when knocking down the first domino in the chain of a person’s existence, set them crashing onto a course of penury and a lifetime of labour, then that was a perfectly acceptable, divinely-sanctioned outcome. The poor, like all other human beings, had the liberty to choose to take action and attempt to improve their situation, but if their actions did not effect a positive change, that indicated poverty was God’s intended outcome for them. As Elaine Freedgood articulates it, Martineau’s viewpoint positioned economic principles “as counterparts of the natural, immutable, and inevitable laws of the physical sciences, and…of God as their metaphysical author” (1).

Figure 3. William Hogarth. Industry and Idleness: "The Fellow 'Prentices at their Looms." 1794-1812, © The Trustees of the British Museum.

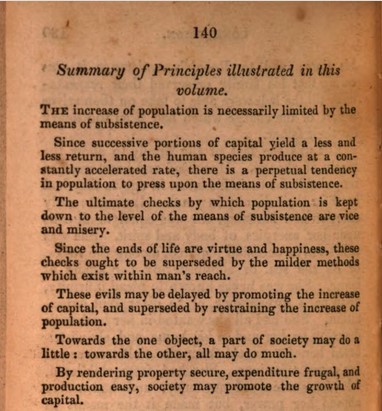

The practical form which Martineau’s metaphysical beliefs took was political economics, a set of theories which Martineau first encountered under that name in Jane Marcet’s Conversations on Political Economy. Marcet’s work explained the tenets of an economic theory based on works by the likes of Adam Smith and Thomas Malthus, who (to oversimplify a complex theory) were concerned with the finite nature of resources in Britain, and the limitations those finite resources placed on the capitalist’s ability to finance labour and production. The political economists’ solution to what they perceived as the inevitability of scarce resources, was to push the working classes into labour whenever possible, and to limit the working class’s consumption of resources by controlling the numbers of their population. Marcet and Martineau presented these ideas in a pseudo-humanitarian guise, characterizing ideas which put the burden of responsibility for their unfortunate situation on the poor themselves as charitable self-improvement solutions. Marcet presents her aim of pushing the working classes into productive labour as “excit[ing] greater attention in the lower classes to their future interests” (167), while limiting the reproduction of the working classes is a helpful measure to aid in “averting or at least alleviating the misery resulting from an excess of population” (161). Along with her socioeconomic opinions, Martineau also learned from Marcet the style of introducing the technical systems of political economy to a wider audience through simple literary forms. Marcet’s example inspired Martineau to explain her principles “not by being smothered up in a story, but by being exhibited in their natural workings in selected passages of social life” (Autobiography 124).

Figure 4. The principles illustrated in Weal and Woe in Garveloch, illustration VI. HathiTrust Digital Library.

The years leading up to the publication of the Illustrations were plagued by turmoil, both in Martineau’s career, and in England’s social, political, and economic affairs. The need for guiding metaphysical philosophies like Necessarianism and practical theories like political economics became more and more clear to Martineau as she witnessed a raging cholera epidemic, “regarded with as much horror as a plague of the middle ages” (Autobiography 139), while the Reform Act and the Corn Laws wreaked havoc on individual lives and the traditional structures of English socioeconomic hierarchy. The news was fraught with accounts of protests for “annual Parliaments, universal suffrage, repeal of the corn laws, abolition of tithes, equitable adjustment of contracts,” and apprehension among the upper classes that “this feeling [of discontentment] is rapidly spreading amongst the working people” (April 1827, London Times 2). Martineau, observing such widespread difficulties, was finally prompted by a bout of machine-breaking in 1827 to publicly address current events in her writing. The short stories Principle and Practice and The Rioters served as prototypes for both the narrative form and the timely discussion of contemporary affairs which would later become central to the Illustrations’ eventual success. Although multiple publishers rejected her proposals for the printing of the Illustrations, Martineau eventually found her salvation in the forms of Charles Fox and William Johnson Fox, the publisher and editor, respectively, of the same monthly magazine in which Martineau had seen her print debut as a teenager. Despite the Foxes’ resistance to the proposed format of the Illustrations, and their doubt as to the financial viability of the enterprise, Martineau’s belief in her principles and in the necessity of the Illustrations didn’t waver. She continued to insist that “the people want this book, and they shall have it” (144). Well, have it, the people did. Funded by the subscriptions the Foxes insisted on, along with some capital provided by her cousin David, Martineau at last got to distributing the prospectus of the Illustrations to its intended audience: “almost every member of both Houses of Parliament” (147). Her boldness in addressing such powerful men directly paid off, as did her conviction that the Illustrations would be a success. Upon the publication of the Illustrations,

The entire periodical press, daily, weekly, and, as soon as possible, monthly, came out in my favour ...Members of Parliament sent down blue books through the post-office, to the astonishment of the postmaster…Half the hobbies of the House of Commons, and numberless notions of individuals, anonymous and others, were commended to me for treatment in my series. (150)

Martineau effectively addressed issues as they arose, spoke publicly about them when they were fresh in the minds of her audience, and joined the discussions in the periodical press, which was frequently weaponized by politicians seeking to promote, question, or condemn new bills of legislation. Her alliance with contemporary politicians during the initial stages of Illustrations’ publication would only grow in strength. The demand for Illustrations grew with every new Act and controversy, as opponents and supporters of such events clamoured to have Martineau address their concerns in her work. Martineau became even more certain that her initial faith in her Illustrations was justified:

My publisher wrote…that the London booksellers need not have been afraid of the Reform Bill, any more than the Cholera, for that during this crisis, he had sold more of my books than ever. Every thing indeed justified my determination not to defer a work which was the more wanted the more critical became the affairs of the nation.” (174)

Her publisher was correct in his assessment. Addressing current events and issues was key to Martineau’s success as an author and to her growing prominence as a public figure. “Sowers not Reapers" was the “Anti-Corn Law tale” (Autobiography, 193), while “The Loom and the Lugger” was a discussion of free trade (192), but the instance which best documents the connections between public presence, political influence, and the unique publication scheme of the Illustrations is the commission and publication of Poor Laws and Paupers Illustrated, a miniseries in the Illustrations of Political Economy. When Lord Brougham wanted to promote the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act, he called on Martineau to write a short propaganda series in favour of the act. The Amendment’s intent, to “produce rather negative than positive effects . . . to remove the debasing influences to which a large portion of the labouring population is now subject” (Reports from the Commissioners for the Poor Law, 205) (that is, to remove obstacles to the poor helping themselves, rather than providing material assistance) was precisely in line with Martineau’s own approach to solving the problems caused by poverty. Although The Poor Law Amendment Act, and Martineau’s series about it, were badly received as heartless and brutal, the entire episode is proof of Martineau’s success as a critic of contemporary affairs. Commissioned by a contemporary politician and inspiring controversy through her periodical writings, which then prompted response from politicians writing for other periodical works like the Times, the Quarterly Review, and the Edinburgh Review, Martineau had achieved her goal of making political economics known to the public, and of supporting real political change, whether that change was for good or ill.

WPHP Records Referenced

Harriet Martineau (person, author)

Illustrations of Political Economy (title)

Joseph Priestley (person, author)

Jane Marcet (person, author)

Conversations on Political Economy (title)

Principle and Practice (title)

The Rioters (title)

Charles Fox (firm)

Sowers not Reapers (title)

The Loom and the Lugger Part I (title)

Poor Laws and Paupers Illustrated: The Parish (title)

Works Cited

Freedgood, Elaine. "Banishing Panic: Harriet Martineau and the Popularization of Political Economy," in Victorian Studies, vol. 39, no. 1, 1995, pp. 33–53.

Hobbes, Thomas. Leviathan, edited by A. R. Waller, Cambridge UP, 1904.

“Manchester Goods Market." London Times, 19 Apr. 1827.

Marcet, Jane. Conversations on Political Economy. Longman, 1819.

Martineau, Harriet. Autobiography, edited by Linda H. Peterson. Broadview, 2007

Priestley, Joseph. “The Doctrine of Philosophical Necessity Illustrated.” Theological and Miscellaneous Works, vol. 3.

Reports from His Majesty’s Commissioners for Inquiring into the Administration and Practical Operation of the Poor Laws, vol, 27, 1834.