This post is part of our Women & Philosophy Spotlight Series, which will run through March 2022. Spotlights in this series focus on women philosophers in the database.

Authored by: Kate Moffatt, Michelle Levy, Tamanna (Tammy) T.

Edited by: Kandice Sharren

Submitted on: 04/01/2022

Citation: Moffatt, Kate, Michelle Levy, and Tamanna T. "Anna Letitia Barbauld’s Writing and the Problem of Genre." The Women's Print History Project, 1 April 2022, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/104.

Figure 1. Barbauld in Richard Samuel's "Portraits in the Characters of the Muses in the Temple of Apollo" (top row, second from the left), oil on canvas, 1778. National Portrait Gallery.

Figure 1. Barbauld in Richard Samuel's "Portraits in the Characters of the Muses in the Temple of Apollo" (top row, second from the left), oil on canvas, 1778. National Portrait Gallery.

Anna Letitia Aikin Barbauld’s first publication, Essays on Song-Writing, co-authored with her brother John Aikin, appeared in 1772. Her last publication in the WPHP is the twenty-eighth edition of Hymns in Prose, published in 1836, eleven years after her death. Many of Barbauld’s works continued to be reprinted throughout the nineteenth century, but we record title data only up until 1836. During the fifty-three lifetime years of her career in print, and the eleven posthumous years recorded in the WPHP, Barbauld’s writing appeared in 44 first editions of titles, and we record an additional 123 in reprints, for a total of 167 separate title records (these figures include a few of her American titles, which we are in the process of adding). This spotlight surveys her career in print in the UK during 1772 to 1836 with a few aims in mind. We use this spotlight as an opportunity to discuss the generic breadth of Barbauld’s writing, thus elucidating her position as an influential thinker in a wide variety of domains. We also use this spotlight as an opportunity to think through the genre categories in the WPHP, and in particular how it is one of the most interpretive and therefore trickiest of our data fields. By examining how we designate genre in our data model and the complications embedded in this process, we address the challenges of capturing, in data, the capaciousness and complexity of Barbauld’s (and many other women’s) careers. Further, we use this spotlight as an attempt to document the prevalence and significance of reprinting to her career and legacy. The interplay of genre and reprinting—that is, what genres get reprinted the most, and why—is also a key question we seek to address. In asking these questions about Barbauld’s career in print, we hope to elucidate the many kinds of writing within which philosophical thinking is found, from writing for children to poetry, from literary criticism to the more traditional essays in which we might expect to find philosophical discourse.

Barbauld’s titles have 15 different WPHP genres attached to them, as follows:

- Juvenile Literature

- Religion/Biblical

- Education

- Poetry

- Political Writing

- Essays

- Poetry Collection

- Fiction

- Music

- Literary Criticism

- Fiction Novel

- Works

- Memoirs

- Annual Periodicals

- Letters

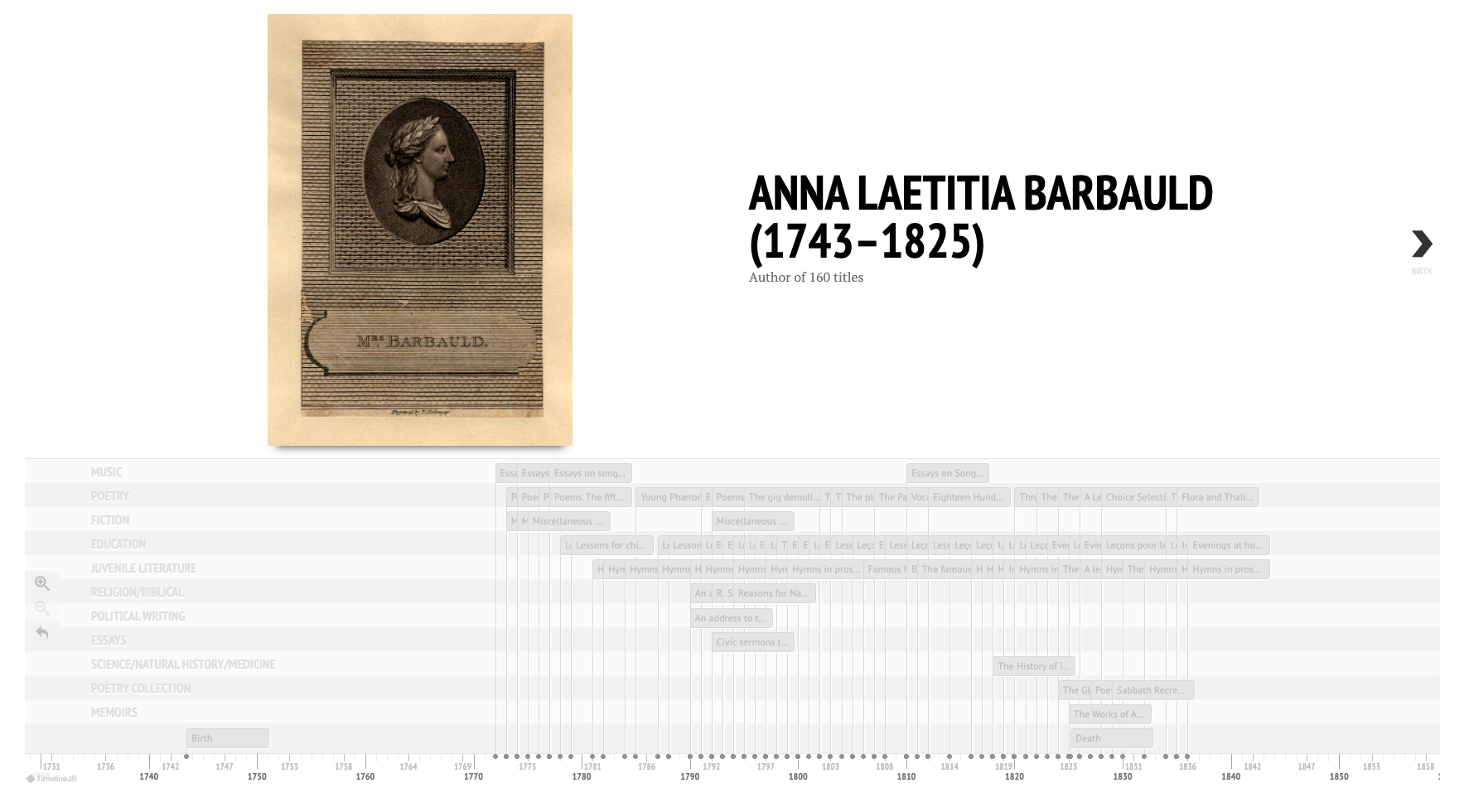

We can see how these genres appear in a preview of a new timeline visualization feature that is coming soon to the WPHP. This timeline helps us to present the myriad data we have in our person and title records, connecting a person’s birth and death dates with the year and genre of their publications.

Figure 2. WPHP timeline prototype for Anna Letitia Barbauld, showing the entirety of her career, early March 2022.

Figure 2. WPHP timeline prototype for Anna Letitia Barbauld, showing the entirety of her career, early March 2022.

This single genre categorization allows us to see the diversity of Barbauld’s career. But it also reflects a simplification, arguably an oversimplification, as most of her titles are not easily confined to a single genre. Indeed, in a review of the WPHP, published in SHARP News last year, Leah Orr raised this issue for us directly:

The editors have attempted to indicate the variety of eighteenth-century genres by categorizing fiction and poetry into subcategories using terms from title pages (“Fiction Romance” or “Fiction Tale,” for instance), but these are sometimes unclear. Consider a work like Hannah More’s Sacred Dramas: Chiefly Intended for Young Persons: The Subjects Taken from the Bible. To Which is Added, Sensibility, a Poem (1782). The Project categorizes this as “Religion/Biblical,” but it could also be relevant to scholars of children’s literature, drama, or poetry. The editors evidently recognized this because the “second,” “third,” and “fourth” editions of this same work are categorized as “Juvenile Literature” (while an unnumbered 1784 edition is also “Religion/Biblical”). Adding more genre designations to each book might capture some of these complexities.

The inconsistency in genre categorization for Sacred Dramas that Orr recognizes is in part a function of the fact that our data model at the time allowed for us to assign only one genre per title, and the fact that we have many people working on our title records, who reached different conclusions about what single genre should be assigned.

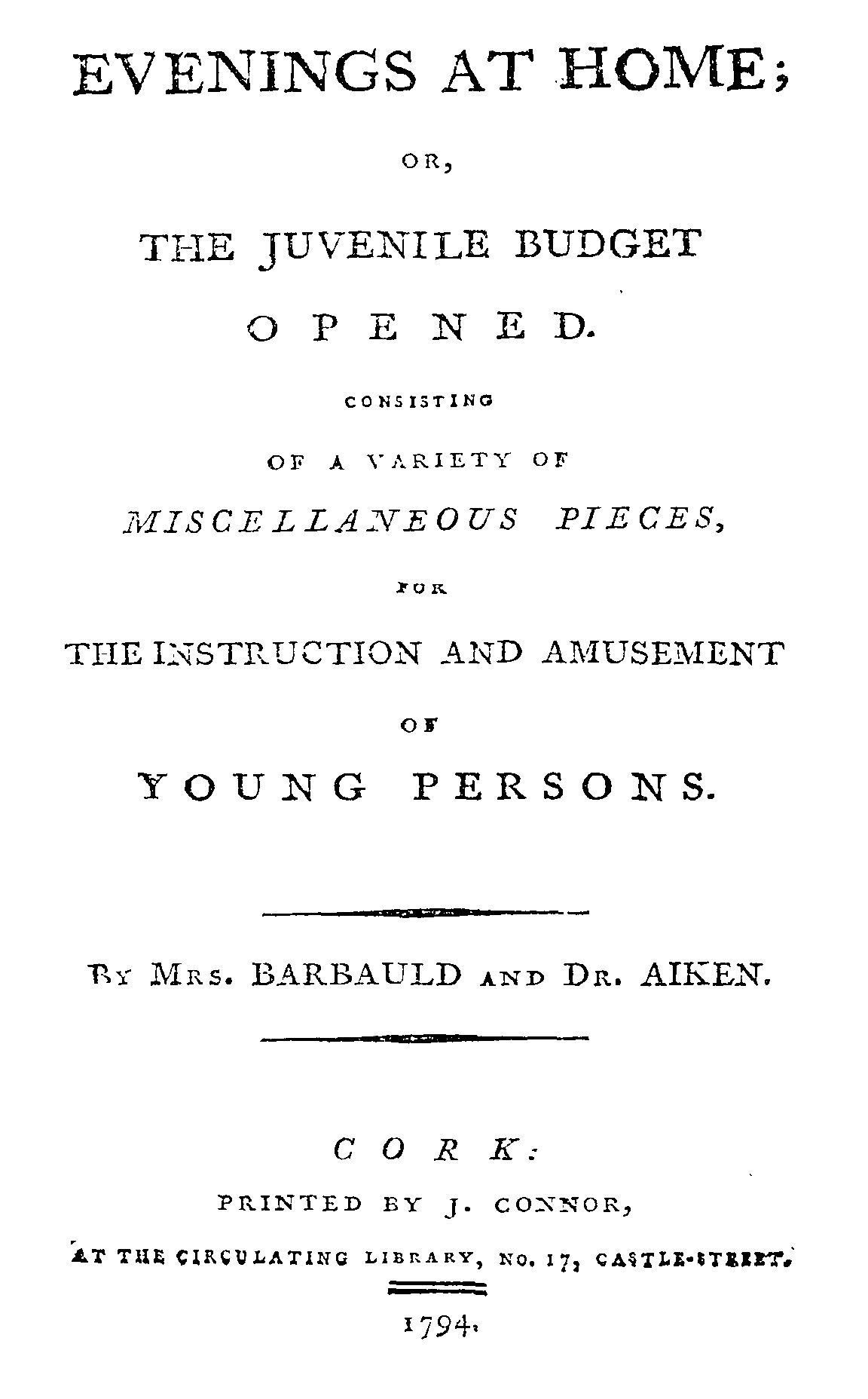

Based on this feedback, we sought a change to our data model to include more than one genre, and have since used Barbauld as a test case to study its implementation. However, even with the flexibility to add multiple genres for each title, we face another set of problems. Barbauld’s Evenings at Home, which had been categorized as Juvenile Literature, offers a challenging example similar to More’s Sacred Dramas. In terms of literary genres, it collects poetry and prose. This kind of collection could also be called a miscellany, another one of our generic terms. It also illuminates, through its content, Barbauld’s educational theory, as well as being deeply political in its insistence that children are political agents, capable of rational judgment and action, and that the domestic home is the necessary site of their political education and even activism. The pieces that make up Evenings at Home are also deeply invested in religion and science. So, how should Evenings at Home be generically categorized? As with Sacred Dramas, it is addressed to a youthful audience, but it adopts other literary and publication forms, and addresses more subject areas than the bare designation of Juvenile Literature would suggest.

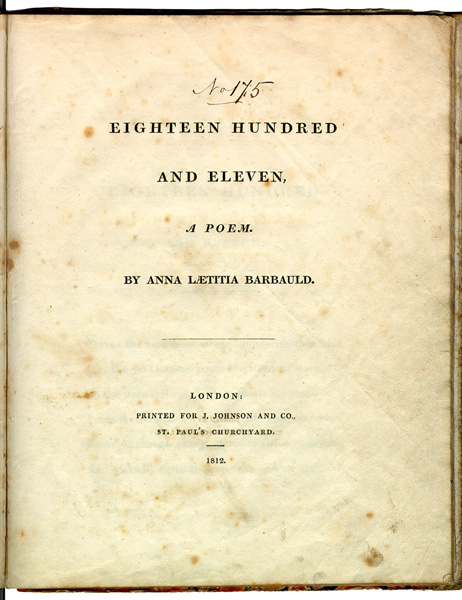

But the problem is not limited to Evenings at Home. A similar question arises in relation to her 1773 Poems. It is Poetry, of course, but many of the poems included are politically-oriented: “The Mouse’s Petition” condemns animal cruelty, “Summer Evening’s Meditation” addresses the extent to which humankind, and perhaps especially women, should rein in thought, or be allowed “to stretch her powers / In flight so daring.” But poems on similar themes are found in many if not most poetry volumes of the day, and, as a bibliographical database, we cannot read every volume of poems to make the determination as to whether they are also political, or scientific, and so on. So, with Poems, we have made the decision to stick with Poetry as the single genre category. But what about the 1792 edition of Poems, in which Barbauld includes “An Epistle to William Wilberforce,” a poem castigating Parliament for rejecting the bill to abolish the slave trade? This is a poem that directly speaks to a Parliamentary vote; even if we had not classified the earlier edition of Poems as Political Writing, should the inclusion of this poem now render the volume worthy of this genre classification? And what about the stand-alone edition of the Epistle? And her later stand-alone publication, Eighteen-Hundred and Eleven, a searing indictment of the British government for its involvement in the war against France and its imperial project? Should these be categorized as Poetry and Political Writing, but not the previous volumes?

Nearly every volume of poetry, and many novels, written during the period engage in political commentary, whether directly or implicitly, but categorizing all of them as such would render the category meaningless. Even if we were to give all of Barbauld’s poetry titles the category of Political Writing, this designation would mostly be a function of our familiarity with her poetry. This same level of knowledge is unlikely to be applied with consistency across our dataset. The problem of inconsistency which Orr observes in relation to More’s Sacred Dramas becomes more profound and potentially distorting as we seek to do more descriptive work which relies on background knowledge that we do not possess for all of our titles (a common theme in several of our podcast episodes: see “Women in the Imprints,” “Oh! Those Fashionable Burney Novels!,” “The Ecology of Databases”).

Figure 3. Title page of the first edition of Eighteen-Hundred and Eleven (1812), which falls into

Figure 3. Title page of the first edition of Eighteen-Hundred and Eleven (1812), which falls into

the Poetry and Political Writing genres in the WPHP. Wikimedia Commons.

But categorizing the titles at all first requires us to generate a list of genres that reflects the writing included in the WPHP. In looking at our genre list, we can see that many of our genres fall into what are broad literary categories: Biography, Drama, Essays, Fiction, Poetry, Juvenile Literature, Letters, Literary Criticism, Memoirs, Travel. Some of our genres, however, are more subject-based, as they delineate fields of inquiry beyond what the literary genres describe, for example: Domestic, Education, History, Legal, Political Writing, Religion, Science. Other genres describe more publication types, such as Catalogue, Poetry Collection, Miscellany, and Works. All of these categories help specify the content of a work, but using multiple genres also poses challenges. How helpful is it to describe Evenings at Home as five or six genres? Is Poems more political than domestic? Or is it both, plus science and religion?

One of the other consequences of being able to add multiple genre categories per title is that it complicates how we can analyze and visualize the data. For this spotlight, we are experimenting with attaching multiple genres to Barbauld’s works in the interest of more accurately reflecting how her writing often engages in a range of subjects and forms simultaneously, and we are also thinking about how best to portray that data. Once combinations of genres are allowed, it is no longer as simple as counting how many titles are designated “Juvenile Literature” and how many are “Poetry,” as we need to be able to account for the combinations of genres she published in, and determine what percentage of her titles fall into each genre individually to capture the generic scope of Barbauld’s work for this spotlight. To that end, we have created multiple spreadsheets that display the genre breakdowns of Barbauld’s titles in the WPHP.

Figure 4. Title page of the 1794 Cork edition of Evenings at Home, which falls into the

Figure 4. Title page of the 1794 Cork edition of Evenings at Home, which falls into the

Education, Juvenile Literature, Religion/Biblical, and Political Writing genres

in the WPHP. NCCO.

We needed multiple spreadsheets to fully understand the genre data for Barbauld’s titles. The first spreadsheet includes all of her titles and identifies each time a genre is used, whether it is the only genre added to a title or appears alongside other genres. This allows us to see how many titles of Barbauld’s total are in any given genre. For example, Evenings at Home has four different genres attached—Education, Juvenile Literature, Religion/Biblical, and Political Writing—and so it is included in each of those genre columns in this spreadsheet. We can see that out of Barbauld’s total 167 titles, Juvenile Literature is attached (including in combination with other genres and as the sole genre) to 98 titles, Poetry to 37, Religious/Biblical to 65, and so on. The second spreadsheet also accounts for all of her titles, but it counts the different combinations of genres that occur in them. For example, Evenings at Home falls under the Education; Juvenile Literature; Religion/Biblical; Political Writing combination; Eighteen Hundred and Eleven and Epistle to William Wilberforce fall under the Poetry; Political Writing combination. Other combinations include Juvenile Literature; Education, Political Writing; Religion/Biblical, and Poetry; Juvenile Literature; Essays, and so on. Accounting for the different genre combinations Barbauld published allows us to see which of her works fall into the same combinations, and identify common patterns or themes.

Because the WPHP accounts for both first editions and reprintings of an author’s works, we have many title (and hence genre) entries for a frequently reprinted title like Evenings at Home. We include reprintings in the WPHP as important indicators of a title’s continuing popularity and influence, including beyond an author’s death; combining all editions and reprintings when counting a genre tells us about the dominance of that genre over the period of time the WPHP covers. But we realized it was important to also capture data about genres for first editions alone, too, as counting only first editions tells us more about the diversity of genres that characterize Barbauld’s written output. So we created a third spreadsheet that includes only the first editions attached to Barbauld in the WPHP to identify every time a genre is used for one of her 44 first editions, whether it is the only genre added or in combination with other genres: according to this spreadsheet, Juvenile Literature is attached to 21 titles, Poetry to 18, Religion Biblical to 15, and so on. Counting each time a genre is used in Barbauld’s first editions shows us how many of her titles belong to each, and therefore also how much Barbauld published in a particular genre. A fourth spreadsheet counts the genre combinations that occur in her 44 first editions, and includes such combinations as Education; Juvenile Literature; Religion/Biblical; Political Writing and Literary Criticism/Critical Editions; Fiction Novel.

But how to discuss Barbauld’s contributions to particular genres when Evenings at Home, for example, appears in four: Education, Juvenile Literature, Religion/Biblical, and Political Writing? For ease of considering her broader contributions to individual genres, we decided to return to our original data model for the genre field by identifying a single, main genre for each of her first editions in a fifth spreadsheet, from which we could then see her major contributions to each genre. In this fifth spreadsheet we have columns that list the following: the titles of her first editions; the year they were published; their current genre status in the WPHP (often a combination of two or more genres); and a final column containing a single genre for each title, chosen from the genres currently attached to them, that we consider to be their “main” genre. The discussion below adopts this approach by grouping her titles into one major genre and discussing these titles, by major genre, as a group.

First editions of Barbauld's works, by genre:

Juvenile Literature

- Lessons for children, from three to four years old. (1778)

- Hymns in prose for children. By the author of Lessons for children. (1781)

- Lessons for children, from two to three years old. (1787)

- Lessons for children of three years old. Part I. (1788)

- Lessons for children, of three years old. Part II. (1788)

- Evenings at home; or, the juvenile budget opened. Consisting of a variety of miscellaneous pieces, for the instruction and amusement of young persons. Vol. I. (1792)

- Evenings at home; or, the juvenile budget opened. Consisting of a variety of miscellaneous pieces, for the instruction and amusement of young persons. Vol. II. (1793)

- Evenings at home; or, the juvenile budget opened. Consisting of a variety of miscellaneous pieces, for the instruction and amusement of young persons. Vol. III. (1793)

- Evenings at home; or, the juvenile budget opened. Consisting of a variety of miscellaneous pieces, for the instruction and amusement of young persons. Vol. IV. (1794)

- Evenings at home; or, the juvenile budget opened. Consisting of a variety of miscellaneous pieces, for the instruction and amusement of young persons. Vol. V. (1796)

- Evenings at home; or, the juvenile budget opened. Consisting of a variety of miscellaneous pieces, for the instruction and amusement of young persons. Vol. VI. (1796)

- The Female Speaker; or, Miscellaneous Pieces in Prose and Verse, Selected from the Best Writers, and Adapted to the Use of Young Women by Anna Lætitia Barbauld. (1811)

- A Legacy for Young Ladies, Consisting of Miscellaneous Pieces, in Prose and Verse by the late Mrs. Barbauld. (1826)

Barbauld published more titles in this genre than any other, and when we add reprintings it was the genre she published in the most frequently. This is unsurprising, considering Barbauld’s experience with teaching and her investment in education. She was considered a “surrogate mother” to the young boys studying in the school she and her husband ran in Palgrave, Suffolk (McCarthy ix), where she wrote Hymns in Prose for Children. In this work, “Barbauld seeks to effect an immersion in pleasurable sensory impressions, directing the child’s whole being towards God” (McCarthy 60). The four-book series of Lessons that first appeared in 1778 is considered to be revolutionary in juvenile literature: written for children as young as two, Barbauld noticed that she knew of no books “adapted for the comprehension” of very young children (“Advertisement,” Lessons for Children, from two to three years old). She also demanded the use of larger typography and white space to render print legible to children. In Evenings at Home, the miscellany she wrote with her brother, they treated children as educational and political subjects, capable of rational thought and the exercise of political agency. It was regularly reprinted across the Atlantic up to the twentieth century (McCarthy 324). By insisting that children had minds that should be cultivated but needed to be addressed on their own terms, Barbauld both theorized and implemented radically new understandings of child development and their cognitive and moral autonomy (Levy, "Radical Education").

Political Writing

- An address to the opposers of the repeal of the Corporation and Test Acts. (1790)

- Civic sermons to the people. Number I. (1792)

- Civic sermons to the people. Number II. From mutual Wants springs mutual Happiness. (1792)

- Sins of government, sins of the nation; or, a discourse for the fast, appointed on April 19, 1793. By a volunteer. (1793)

- Reasons for National Penitence, recommended for the fast, Appointed February XXVIII. 1794. (1794)

Between 1790 and 1794, Barbauld published several pamphlets with the aim of defending “ethical politics in an evil time” (McCarthy 309). In An Address, Barbauld protested religious intolerance and legalized discrimination against Dissenters. In Sins of Government, she protested Britain’s entry into the war against France. Often in these political pamphlets, Barbauld sought to educate an adult audience about political literacy (McCarthy 323). Throughout her political writings, Barbauld urged her readers to question the government and its decisions, advocating for peace and tolerance. Her insistence on these social values, and how they should structure our relations with one another and in our relation to the state, is reflected throughout her writing.

Poetry

- Poems. (1773)

- Epistle to William Wilberforce, Esq. On the rejection of the bill for abolishing the slave trade. By Anna Letitia Barbauld. (1791)

- Eighteen Hundred and Eleven: A Poem. By Anna Letitia Barbauld. (1812)

Barbauld’s reputation was made through her poetry, and her verse circulated in manuscript at Warrington and beyond in the 1760s and 1770s before her brother prevailed on her to collect and publish her verse. Her Poems was immediately successful, and reprinted 10 times. As discussed above, her poems touch upon many fields of thought and may be considered philosophical in their broad remit. She explores our relations to each other, to animals, and to God. She asks about the constraints placed on women, or what should constitute “a women’s universe,” in her poem “A Summer Evening’s Meditation” and challenges Warrington patriarchy, voicing resistance to containing her “Epictetan self” (McCarthy 94–95). Poems also called attention to Barbauld’s defiance of a conception of God as male, particularly in her poem “Meditation” (McCarthy 95). Her last published poem, Eighteen Hundred and Eleven, was written to protest British government’s policy regarding the war with France, and for this she suffered social abandonment by many of her friends (McCarthy xiv), as well as outrageously sexist and cruel attacks from reviewers.

Literary Criticism

- The Pleasures of Imagination. By Mark Akenside, M.D. to Which is Prefixed A Critical Essay on the Poem, by Mrs. Barbauld. (1794)

- The Correspondence of Samuel Richardson, Author of Pamela, Clarissa, and Sir Charles Grandison, Selected from the Original Manuscripts, Bequeathed by him, to his Family. To which are Prefixed a Biographical Account of that Author, and observations of his writings, by Anna Laetitia Barbauld. (1804)

- Selections from the Spectator, Tatler, Guardian and Freeholder, with a Preliminary Essay, by Anna Letitia Barbauld. (1804)

- The British Novelists; with an Essay; and Prefaces, Biographical and Critical, by Mrs. Barbauld. (1810)

Throughout her literary career, Barbauld wrote many reviews in periodicals, which we do not include in the WPHP as we do not address periodical writing. She was also an editor, who published Akenside’s poem and the correspondence of Samuel Richardson. Through her editing of these works and through her prefatory essays, she engaged in literary criticism, although her most famous effort is the fifty-volume anthology, The British Novelists, a monumental undertaking published in 1810 and reprinted in 1820. For each of the novels she included, she wrote a short prefatory essay, engaging in both biography and criticism and seeking to create a new canon of the eighteenth-century novel (Claudia Johnson, “‘Let me make the novels of a country’: Barbauld’s The British Novelists (1810/1820”). Furthermore, in volume 1 of The British Novelists, Barbauld wrote an engaging and important essay, “On the Origins and Progress of Novel-Writing,” that defended the novel, the subject of so many contemporary attacks, “condemned by the grave, and despised by the fastidious.” As in Jane Austen’s more famous defense of the novel in chapter 5 of Northanger Abbey, not published until 1818, in 1810 Barbauld notices that though the novel was easy to deride, “their leaves are seldom found unopened.” Barbauld’s case for the novel depends on the pleasure novels give readers, as the novel both reflects and influences the manners, sentiments, and sensibilities of its time.

Barbauld’s The British Novelists is another example of the challenges of using WPHP genre data alone to understand an author’s involvement in particular genres. Fifty volumes long, and constituting thousands of pages, The British Novelists is one of the largest title records in the WPHP—but it counts as only a single work, which means it is captured by a single title entry in the WPHP, and therefore a single record in our genre counts for Literary Criticism/Critical Editions and Fiction Novel. To further complicate things, this title (and a few others) is included as Fiction Novel is in our genre data for Barbauld, despite Barbauld herself not having authored any of the novels.

Essays

- Essays on Song-Writing: with a collection of such english songs as are most eminent for Poetical Merit. To which are added, some original pieces. (1772)

- Miscellaneous Pieces, in Prose, by J. and A. L. Aikin. (1773)

Although we include only two works under the genre of Essays, the essay was a central form for Barbauld. Most of her political writing took the form of the essay, and many unpublished essays appeared in her Works, after her death. Miscellaneous Pieces in Prose contains many different forms of writing—the allegorical “The Hill of Science”, the prose poem “Seláma, an Imitation of Ossian”, the historical essay “On Monastic Institutions” and literary essays such as “An Enquiry into Those Kinds of Distress Which Excite Agreeable Sensations” (McCarthy 111).

Religion/Biblical

- Devotional Pieces, compiled from the Psalms and the Book of Job: to which are Prefixed, Thoughts on the Devotional Taste, on Sects, and on Establishments. (1775)

- Remarks on Mr. Gilbert Wakefield's Enquiry into the expediency and propriety of public or social worship. (1792)

Barbauld was born and baptized into English Protestant Dissent, and her religion was an integral aspect of her life and permeates all of her writing, from her Hymns in Prose to her political sermons. Devotional Pieces, according to William McCarthy, was a culmination of important models of the Enlightenment—“philosophy enquiry” and “natural history” and she explored the idea of devotional imagination through “taste” (148). In Remarks, she defends the practices of social worship.

Works

In 1825, Lucy Aikin published The Works of Anna Letitia Barbauld, including both published and unpublished writing by her aunt as well as a short memoir. This volume brought to light many unknown poems and essays.

One additional complication of our genre work is the fact that we account for titles in our data that include writing by Barbauld, but whose publication was not necessarily overseen by Barbauld herself. Because she was such a popular writer, we find that many of her poems and juvenile writing were reprinted in collections by other editors, compilers, and authors. For example, The Promise. A Poetic Trifle is a collection of poems that include one riddle by Barbauld; as such, it is included in the WPHP, and Barbauld is listed in its title record as an author. But this is an example of a title that may skew our understanding of Barbauld’s contributions to particular genres if we do not account for its being a work overseen by someone else. As a result, in the discussion above, we do not consider the titles that include her writing but were not published by her. We have grouped them here by their main genre.

Genres of first editions containing Barbauld’s writing but not overseen by Barbauld, by genre

Poetry

- Poems: By Francis Wrangham, M.A., Member of Trinity-College, Cambridge. (1795)

- The Metrical Miscellany: Consisting Chiefly of Poems Hitherto Unpublished. (1802)

- Poetic Gleanings, from Modern Writers; with Some Original Pieces. By a governess. (1827)

- Choice Selections, and Original Effusions; or, Pen and Ink Well Employed. By a daughter of a clergyman. (1828)

- The Promise, a Poetic Trifle. By a young lady. (1834)

- Flora and Thalia; or Gems of Flowers and Poetry; being an Alphabetical Arrangement of Flowers, with Appropriate Poetical Illustrations, Embellished with Coloured Plates. By A Lady. (1835)

- The Seraph: Or, Gems of Poetry, for the Serious and Contemplative Mind: And the Promotion of Genuine Religion. (1835)

Juvenile Literature

- The Female Reader; or, Miscellaneous Pieces in prose and verse; selected from the best writers, and disposed under proper heads; for the improvement of young women. By Mr. Cresswick, Teacher of Elocution. To which is prefixed a preface, containing some hints on female education. (1798)

- Hymns Selected from Various Authors, and Chiefly Intended for the Instruction of Young Persons. (1818)

- The Force of Example: A Nursery Rhyme. From the Celebrated Lessons for Children by Mrs Barbauld. (1822)

- The Gleaner, a Selection of Poems for Youth. (1824)

- The three cakes; or, Harry, Peter, and Billy. A tale in verse. Illustrated with engravings. From the original in prose by Mrs. Barbauld. (1824)

- An interlineary translation of Barbauld's 'Hymnes en prose.' Designed to assist young children in acquiring a vocabulary of the French language. (1828)

Annual

Figure 5. William Holland, "Don Dismallo Running the Literary Gantlet [sic]," 1790. British Museum.

Figure 5. William Holland, "Don Dismallo Running the Literary Gantlet [sic]," 1790. British Museum.

As we think this spotlight has amply demonstrated, any attempt to grapple with genre, even for a single (albeit prolific) writer, is fraught with complications. We note the many generic crossovers in her writing, and how difficult this makes the work of assigning genre categories, whether we limit ourselves to one or allow for many. It should be noted that Barbauld’s career was marked by the highest praise for her writing and for her as an inspirational figure, as may be seen in the image we used to illustrate both the start of this Spotlight, and our Women and History Spotlight Series last year, in Richard Samuel’s group portrait of 1778 where Barbauld appears as one of the nine muses (she is depicted second from the left, with her left hand outstretched). But her work on education and writing for children was also used against her: in a 1790 illustration (shown above) she is portrayed, third from the left, as a school mistress brandishing a cat o’ nine tails to whip Edmund Burke for his offences against liberty (in his attack on the French Revolution), and later, in 1812, she was savagely treated by John Wilson Croker in his unsigned Quarterly Review of Eighteen Hundred and Eleven for “exchanging the birchen for the satiric rod,” viciously condemned for leaving off writing for children where she was considered useful and instead daring to address the state of the nation. Of course, Croker’s attempt to pin Barbauld to her role as a writer for children grossly mischaracterizes her career, but it demonstrates the political force, and damage to women, that generic type-casting, as it were, could hold. How we choose to characterize our title records by genre will of course be much less controversial and potentially damaging, but, as this foray into the many complications and possibilities for the work of genre classification suggests, it remains a fraught endeavor.

WPHP Records Referenced

Anna Letitia Barbauld (person, author)

John Aikin (person, contributor)

Hymns in Prose for children. From the author of Lessons for children (title)

Hannah More (person, author)

Evenings at home; or, the juvenile budget opened. Consisting of a variety of miscellaneous pieces, for the instruction and amusement of young persons. Vol. I. (1792) (title, first edition)

Poems. (1773) (title)

Epistle to William Wilberforce, Esq. On the rejection of the bill for abolishing the slave trade. By Anna Letitia Barbauld. (1791) (title)

Eighteen Hundred and Eleven: A Poem. By Anna Letitia Barbauld. (title)

The Promise, a Poetic Trifle. By a young lady. (title)

An address to the opposers of the repeal of the Corporation and Test Acts. (1790) (title)

Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme (firm, publisher)

Thomas Cadell (firm, publisher, bookseller)

Remarks on Mr. Gilbert Wakefield's Enquiry into the expediency and propriety of public or social worship. (title, first edition)

Devotional Pieces, compiled from the Psalms and the Book of Job: to which are Prefixed, Thoughts on the Devotional Taste, on Sects, and on Establishments. (title, first edition)

Miscellaneous Pieces, in Prose, by J. and A. L. Aikin. (1773) (title, first edition)

Samuel Richardson (person, author)

Lucy Aikin (person, author)

The Works of Anna Laetitia Barbauld. With a memoir by Lucy Aikin. In two volumes. (title)

Works Cited

Barbauld, Anna Letitia, and Aikin, Lucy. The Works of Anna Laetitia Barbauld: In Two Volumes. United Kingdom, 1825.

Johnson, Claudia L. “‘Let Me Make the Novels of a Country’: Barbauld’s ‘The British Novelists’ (1810/1820).” NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction, vol. 34, no. 2, 2001, pp. 163–79.

Levy, Michelle. “The Radical Education of Evenings at Home.” Eighteenth-Century Fiction, vol. 19, no. 1-2, 2006, pp. 123-50.

McCarthy, William. Anna Letitia Barbauld: Voice of the Enlightenment. John Hopkins UP, 2009.

Orr, Leah. “Michelle Levy et al., The Women’s Print History Project.” SHARP News, 28 April 2021. https://www.sharpweb.org/sharpnews/2021/04/28/michelle-levy-et-al-the-womens-print-history-project.

Wharton, Joanna. Material Enlightenment: Women Writers and the Science of Mind, 1770-1830. The Boydell Press in association with British Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies, 2018.

Further Reading

Bailey, Peggy Dunn. “Barbauld’s ‘Hymns in Prose for Children’: Christian Romanticism and Instruction as Worship.” Christianity and Literature, vol. 59, no. 4, 2010, pp. 603–17.

Crocco, Francesco. “The Colonial Subtext of Anna Letitia Barbauld’s ‘Eighteen Hundred and Eleven.’” The Wordsworth Circle, vol. 41, no. 2, 2010, pp. 91–94.

Johnson, Claudia L. “‘Let Me Make the Novels of a Country’: Barbauld’s ‘The British Novelists’ (1810/1820).” NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction, vol. 34, no. 2, Duke UP, 2001, pp. 163–79.

William McCarthy. “Mother of All Discourses: Anna Barbauld’s 'Lessons for Children.'” The Princeton University Library Chronicle, vol. 60, no. 2, 1999, pp. 196–219.

Barbauld in Richard Samuel's "Portraits in the Characters of the Muses in the Temple of Apollo"

Barbauld in Richard Samuel's "Portraits in the Characters of the Muses in the Temple of Apollo"