This post is part of our Women & Philosophy Spotlight Series, which will run through March 2022. Spotlights in this series focus on women philosophers in the database.

Authored by: Angela Wachowich

Edited by: Michelle Levy

Submitted on: 03/04/2022

Citation: Wachowich, Angela. "(Unidentified) Woman not Inferior to Man: 'Sophia,' Proto-Feminism, and the Anonymous Female Writer." The Women's Print History Project, 4 March 2022, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/97.

Figure 1. Carle van Loo. An Allegory of Comedy, 1752. Wikimedia Commons.

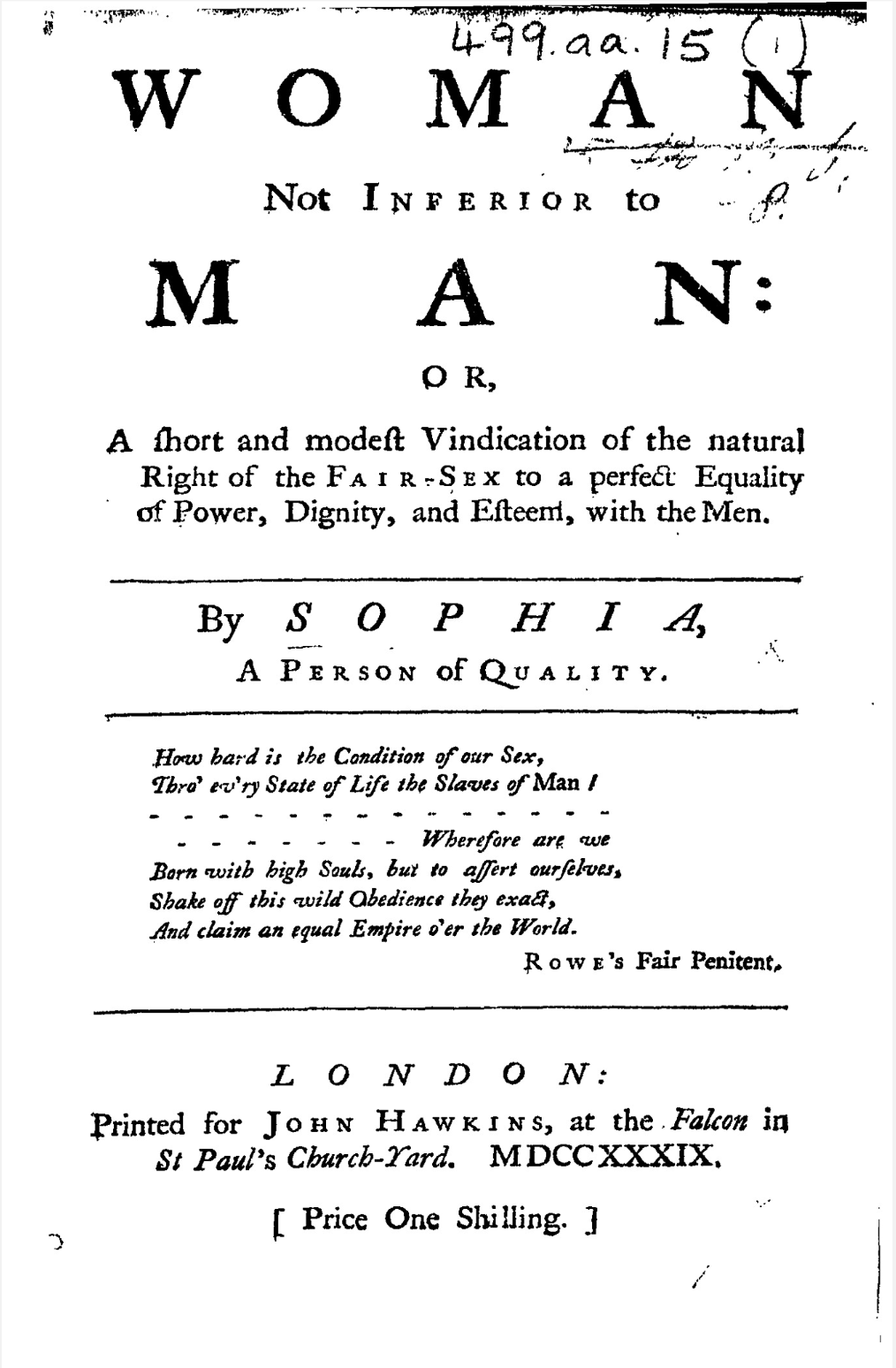

In 1739, in response to contemporary intellectual debate about the nature of women and women’s rights, an anonymous woman, who identified herself as “Sophia, a Person of Quality,” published a pamphlet called Woman not Inferior to Man in London. Woman not Inferior quickly drew the attention of leading intellectual women, such as Elizabeth Carter, who were left to speculate about the identity of the unidentified author (Carter 79). The year of the text’s publication, an anonymous “Gentleman” delivered a rebuttal called Man Superior to Woman (1739), in which he antithetically asserted that Sophia and other women had no right to claim women were equal to men until they could prove women were superior to men (Man Superior 73–74). Sophia accepted the Gentleman’s challenge and returned to the press with Woman’s Superior Excellence Over Man (1740), writing:

since the Men are so ungenerous, as to disallow us this modest pretension [equal right to dignity, power, and esteem], and the gentleman, my antagonist, is so weak as to dispute our equality with the Men, till we can shew a superiority over them; I think it but a justice due to my injured sex to accept of his challenge, and to prove, what is matter of fact, that Woman-kind are not only by nature equal, but far superior to the Men. (12)

Sophia critically supports her dual claims to women’s equality and superiority by asserting that while born equal, eighteenth-century women developed moral superiorities to men as a result of social custom. This proto-feminist argument, influenced by Cartesian and Lockean philosophy and early modern texts such as Lucrezia Marinella’s La nobilità et l’eccellenza delle donne co’diffetti et mancamenti di gli uomini (1600), foreshadows our modern-day understanding of gender as a social construct (Broad, “From Nobility,” 12, 8).

This Spotlight approaches Sophia’s publications—Man Superior to Woman (1739, 1739, 1743) and Woman’s Superior Excellence Over Man (1740, 1743)—from, first, a rhetorical and, then, a biographical perspective. In surveying the philosophical ideas that Sophia uses to support her defense of women’s natural rights, this Spotlight highlights some of the rhetorical strategies employed by proto-feminist philosophers during the eighteenth-century; in examining the significance of Sophia’s pseudonymous authorship, it surveys some of the ways the WPHP represents unidentified authors and considers the impact of female-gendered anonymous authorship on a work’s reception.

Figure 2. Sophia. Title page of Woman Not Inferior to Man, 1739. ECCO.

Proto-Feminist Rhetoric

Sophia’s first work, Woman not Inferior, is not an entirely original work but a liberal translation of François Poulain de la Barre’s De l’égalité des deux sexes (1673). That said, the extent to which Sophia adapted the text has often been underestimated. Since 1916, when C.A. Moore declared that Sophia was a plagiarist and an imposter (196), scholars such as Guyonne Leduc and Jacqueline Broad have stressed the importance of several salient differences between the two philosophers (Leduc qtd. in Broad, “From Nobility,” 1). In addition to adding eighteenth-century quotations and examples of accomplished women to Poulain’s arguments (O’Brien, qtd. in Broad, “From Nobility,” 3), Sophia’s diction and tone convey a more negative opinion of men than Poulain’s original text. This section of the Spotlight surveys three particular philosophical arguments that Sophia uses in concert with and to embellish Poulain’s original treatise, illustrating a few popular branches of eighteenth-century proto-feminist rhetoric.

Both Poulain and Sophia found their arguments upon Cartesian notions of equality, which assume a division between mind and body, allowing for each to exist independently of one another (Broad, “From Nobility,” 4). Seventeenth-century feminists, such as Poulain, used Descartes’ philosophy of mind “to assert their intellectual equality with men; for if, as Descartes argued, mind has no extension [in the body], then it also has no gender” (Gallagher, qtd. in Broad, “Early Modern Feminism,” 72). Proto-feminists like Poulain and Sophia used Descartes’ philosophy of mind to their own ends to argue that the differences between men and women’s intellect must result from “outside causal factors, such as education, religion, and other environmental effects” (Broad, “Early Modern,” 73, 76). Recognizing the importance of societal conditioning to women’s perceived nature also allowed Poulain and Sophia to extoll the superior virtue and generosity manifest in eighteenth-century women as a social group, as exemplified by their caregiving skills (Broad, “From Nobility,” 7). Attributing women’s perceived strengths and weaknesses to conditioning rather than nature allowed Poulain and Sophia to illustrate the impossibility of definitively proving women’s rational equality to men while they stood at an educational disadvantage (though women’s virtues would suggest that their rights merited further consideration).

Figure 3. William Hogarth. Assembly at Wanstead House. 1728-1731, The John Howard McFadden Collection, M1928-1-13. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The suggestion that women’s rights ought to be reconsidered relied upon Descartes’ method of doubt, which encouraged early modern feminists to question and test men’s assumed superiority to and authority over women before accepting its truth (Perry qtd. in Broad, “Early Modern,” 72). To this end, as Leduc’s analyses of Sophia’s ‘translation’ has demonstrated, Sophia diverged from Poulain in applying the diction of popular anti-tyranny discourse to her treatise (Broad, “From Nobility,” 11). For example, Sophia replaced Poulain’s moderate qualifications of women as “subject” to men’s authority with assertions that women were “enslaved” to men’s “tyranny” as a result of “lawless usurpation” (Leduc qtd. in Broad, “Nobility” 3), highlighting the “unnatural violence” and “grosser barbarities” used to maintain men’s authority (Sophia, Woman not Inferior, 10). Sophia argued that women were better qualified for political leadership by virtue of women’s caregiving skills and men’s historically violent leadership. In doing so, Sophia exploited widespread acceptance of Locke’s assertion that a human being cannot voluntarily consent to tyranny (Broad, “From Nobility,” 11–12) and ties her proto-feminism to a larger political conversation about subjugation.

Woman not Inferior and Woman’s Superior Excellence also make use of another popular rhetorical tactic employed by pro-women writers as early as the Renaissance—the citation of exceptional examples of women from history, or, ‘women worthies.’ ‘Women worthies’ are women who were seen as testaments to the power or intelligence of the female sex (Hicks 175), such as the Amazons, Sappho, Queen Anne, and Joan of Arc. As the century progressed, particularly in the 1770s, contemporary women like Elizabeth Carter and Hannah More were increasingly drawn into this tradition, as can be seen in Richard Samuel’s The Nine Living Muses of Great Britain (figure 4). The second of Sophia’s works foreshadows the coming inclusion of contemporary women in the ‘women worthies’ tradition by adding eighteenth-century ‘women worthies’ such as Elizabeth Singer Rowe and Anne Finch to Poulain’s examples of women with a superior aptitude for intellectual, political, and military power (Hicks 178).

That said, Sophia’s rhetorical reliance upon ‘women worthies’ may also have contributed to her texts’ short lives; by the end of the eighteenth-century, the citation of ‘women worthies’ had fallen out of favour in proto-feminist rhetoric. Mary Wollstonecraft, for example, famously rejected the tradition, writing, “I shall not lay any great stress on the example of a few women who, from having a masculine education, have acquired courage and resolution” (A Vindication of the Rights of Woman 224). Wollstonecraft’s political ideals represent a larger philosophical shift towards ideals of radical equality (typified by the French Revolution), in light of which, the citation of a few exceptional women no longer seemed the best way to represent the rights of the whole sex. Therefore, while the tradition of ‘women worthies’ persisted in historical writing, such as Mary Hays’ Female Biography, Sophia’s argumentative reliance on ‘women worthies’ significantly limited her treatises’ afterlives.

Figure 4. Richard Samuel. Portraits in the Characters of the Muses in the Temple of Apollo. 1778, National Portrait Gallery. Left to right: Elizabeth Carter, Anna Letitia Barbauld, Angelica Kauffman, Elizabeth Linley Sheridan, Elizabeth Griffith, Charlotte Lennox, Elizabeth Montagu, Catharine Macaulay, and Hannah More.

Unidentified Woman Writer

Since their publication, Sophia’s treatises Woman not Inferior and Woman’s Superior Excellence have been plagued by questions of attribution. Scholars have alternately taken the author at her word in describing herself as “a Woman” (Women’s Superior 75) of noble birth and speculated that “she” was actually a man (Daniel). Others have asserted that the author of Women’s Superior Excellence was different than the author of Woman not Inferior and Man Superior to Woman (Daniel). Since the eighteenth-century, others have speculated that Sophia was a pseudonym used by a more well-known woman, such as Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689–1762) or Lady Sophia Fermor (1721–1745); however, no compelling evidence supports either claim.

In seeking to capture women’s contributions to print during the long eighteenth-century, the WPHP has opted to include anonymous titles putatively authored by women whose identities are unknown. For example, titles attributed to “a Lady” are assigned to “Unknown, [Woman]”. More information about these authors can sometimes be found in the Signed Author field, where “a Lady” might specify she is “A Young Lady” or “A woman of fashion.” Titles published under pseudonyms, like Sophia, are given their own Person Records. This means that many of the WPHP’s Person Records are limited to a first name, such as Elizabeth, Sabina, and Susanna. We include unidentified anonymous and pseudonymous authors in the database although some of these authors may have misrepresented their genders because we believe it is ultimately more important to account for the women who concealed their identities than to exclude a limited number of male authors who may have misrepresented themselves.

Though the popularity of and reasons for anonymous publication evolved over the course of the century, it is important to remember that, as Jennie Batchelor summarizes, “anonymity was the norm for eighteenth-century [novel] publication, not a deviation from it” (Hidden Histories). Eighty-percent of new (first edition) novels published between 1750 and 1790 were published anonymously (Raven). If an individual were to peel through the Signed Author fields of some of the eighteenth-century’s most well-known texts, they would discover that even beloved authors—such as Frances Burney, Mary Shelley, and Jane Austen—published anonymously at some point in their careers. Unlike these texts, however, most titles “by a Lady” will never be connected to an author.

The question then becomes—What do we gain by considering works by female-gendered anonymous and pseudonymous authors, like Sophia, women-authored texts? The author of Woman not Inferior and Women’s Superior Excellence presented their treaties before the public as a woman’s work. This accordingly shaped the texts’ readership. By specifying that she was “a Person of Quality,” Sophia’s work recommended itself to educated women of a certain status. The assigned gender and class also positioned the author in relation to a growing social movement—proto-feminism—led by white women of the upper-middle classes. The adaptations Sophia made to Poulain are consequently read in relation to the ideas of other British proto-feminist women writers, like Mary Astell and Mary Wollstonecraft. In this sense, the assigned gender and class determined the context by which both contemporary and modern readers read and study Sophia’s texts. Unlike Astell and Wollstonecraft, however, Sophia’s work cannot be understood in relation to their creator’s life. Anonymous and pseudonymous texts like Woman not Inferior challenge feminist literary scholars to extend the work of identifying and recovering texts by subversive women writers to the work of recovering and appreciating the gendered history of texts with unidentified authors.

WPHP Records Referenced

Sophia (person, author)

Woman not Inferior to Man (title, first edition)

Carter, Elizabeth (person, author)

Woman's Superior Excellence over Man (title, first edition)

More, Hannah (person, author)

Rowe, Elizabeth Singer (person, author)

Finch, Anne (person, author)

Wollstonecraft, Mary (person, author)

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects (title)

Hays, Mary (person, author)

Barbauld, Anna Laetitia (person, author)

Griffith, Elizabeth (person, author)

Lennox, Charlotte (person, author)

Montagu, Elizabeth (person, author)

Macaulay, Catharine (person, author)

Montagu, Mary Wortley (person, author)

Unknown, [Woman] (person, author)

Elizabeth (person, author)

Sabina (person, author)

Susanna (person, author)

Burney, Frances (person, author)

Shelley, Mary (person, author)

Austen, Jane (person, author)

Works Cited

Broad, Jacqueline. “Early Modern Feminism and Cartesian Philosophy.” The Routledge Companion to Feminist Philosophy, edited by Garry, Ann, et. al., Routledge, 2017, pp. 71–81.

Broad, Jacqueline. “From Nobility and Excellence to Generosity and Rights: Sophia’s Defenses of Women (1739–40).” Hypatia, 2021, pp. 1–17.

Carter, Elizabeth. Elizabeth Carter, 1717–1806: An edition of some unpublished letters. Edited by Gwen Hampshire, U of Delaware P, 2005.

Daniel, Dominique. “Highlights from the Marguerite Hicks Collection: Sophia (1739–1740).” Oakland University Archives and Special Collections, March 2019, https://library.oakland.edu/collections/special/exhibits/sophia/index.html.

Gentleman. Man Superior to Woman. T. Cooper, 1739.

Hicks, Philip. “Women Worthies and Feminist Argument in Eighteenth-Century Britain.” Women’s History Review, vol. 24, no. 2, 2015, pp. 174–190.

Lewis, Helen. “HH #1.5: Fight Club.” Hidden Histories: The New Statesman History Podcast, 13 May 2016.

Raven, James. “The Anonymous Novel in Britain and Ireland 1750–1830.” The Faces of Anonymity: Anonymous and Pseudonymous Publication from the Sixteenth to the Twentieth Century, Palgrave Macmillan, 2003, pp. 141–166.

Sophia, Person of Quality. Woman not inferior to man. John Hawkins, 1739.

Sophia, Person of Quality. Woman's superior excellence over man. John Hawkins, 1740.

Wollstonecraft, Mary. A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with strictures on political and moral subjects. J. Johnson, 1792.