This post is part of our Down the Rabbit Hole: Researching Women in the Book Trades Spotlight Series, which will run through August 2022. This series seeks to make transparent some of the processes, challenges, and editorial choices our team has to make while falling down the inevitable rabbit holes involved in finding, and creating data for, women in the book trades.

Authored by: Julianna Wagar

Edited by: Michelle Levy, Kate Moffatt, and Sara Penn

Submitted on: 08/19/2022

Citation: Wagar, Julianna. "A Royal Printer: Agnes Campbell in Scotland's Book Trade." The Women's Print History Project, 19 August 2022, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/114.

Figure 1. Imprint from The Principal acts of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. ECCO.

For our “Down the Rabbit Hole: Researching Women in the Book Trades” spotlight series, I was particularly interested in researching a Scottish woman’s firm, and one of the most prolific women in the eighteenth-century Scottish book trades is Agnes Campbell. Campbell worked as a printer for more than forty years, and for the majority of those years, held the position of the King’s and Queen’s Printer. Her career in this role began after she inherited the business from her husband, Andrew Anderson, who died in 1676. Now remembered as “The most wealthy, renowned and misunderstood of . . . successful [Scottish] women, Agnes Campbell, Lady Roseburn (1637–1716), symbolises both the possibilities for women and the condition of the Scottish book trade” (Mann 2). Campbell’s career is well-documented due to this enviable and highly visible position that was mainly occupied by men. Her legacy is more than the 800 works that she printed—it is also her success in maintaining this position as a woman after her husband died for the duration of what was left of their forty-one year patent.

Agnes Campbell was born in 1637 and baptised in Edinburgh on 1 September 1637, to Isobel Orr and James Campbell. In approximately 1635, Andrew Anderson, Campbell’s eventual husband, was born to Isobel Aitcheson and George Anderson. His father was a very successful printer in Glasgow and later Edinburgh, but George Anderson died early in his career and his wife, Isobel, took over the business from 1648 to 1653. Andrew Anderson took over the business in 1653, and it was the beginning of a career that would span twenty-three years, accumulate £7,451 Scottish pounds of debt (ODNB), and end with his death in 1676. From 1653 to 1661, Anderson ran the family business under his own imprint; in 1663, he became the burgh and printer for the University of Edinburgh (ODNB). In 1671, Andrew Anderson was awarded the title of King’s Printer, a highly sought after position which gave him the exclusive right to print political and religious texts, such as the Bible in Scotland, for the reigning King or Queen. Anderson’s patent was for forty-one years. From 1676, the year of his passing, until 1712, however, Agnes Campbell managed this business.

Agnes Campbell is now most commonly referred to as Agnes Campbell, her maiden name, in scholarship; however, throughout her life she was referred to by four names. When working with women, names can be vital for recovering both biographical and business information, and how they displayed themselves on the works they produced can sometimes tell us about their marital or class status. After marrying Andrew Anderson in 1656, Campbell is referred to as “Mrs. Anderson” or “the relict of Andrew Anderson,” linking her back to her husband—and his patent—even after his death (Mann 133). “Mrs. Anderson” and “the relict of Andrew Anderson” both gesture to the fact that she holds this position due to Andrew Anderson’s patent that was passed down to his wife and children. In fact, Agnes Campbell is never named on the title pages of her publications due to the legalities of that patent, which outlined that future imprints must be published under the “heirs and successors of Andrew Anderson” (Mann 137). Campbell is mainly referred to as “the relict of Andrew Anderson” after her patent expires in 1712 (ESTC). Campbell remarries in 1681 to Patrick Telfer; however, she is scarcely referred to as Mrs. Telfer, as they were estranged by 1690 (Mann 135). Her final name is Lady Roseburn, a title that highlights her wealth at the end of her life. Campbell obtained the lands of Roseburn, Dalry in 1704, due to her success in the book trade (ODNB). For this spotlight series, it is important to recognize the challenge of finding women in imprints, as their names often change with marriage or are referred to by their husband’s titles, imprints, or names, like Campbell with Andrew Anderson and his position as the King’s Printer. Part of working on women in the book trades is discovering the various names that women had or printed under in order to find the works they contributed to producing, and to establish as full a picture as possible of their work. In this spotlight, I will use her maiden name and the name she is most commonly remembered by, but not printed under, Campbell.

Figure 2. "Roseburn House." J. R. Russell, Edinburgh. https://www.scotland.org.uk/guide/castles/roseburn-house.

As referenced above, Agnes Campbell printed as the “heirs and successors of Andrew Anderson,” and produced more than 800 works (ESTC) during her 36 years as the King’s and Queen’s Printer, which are still being added to the WPHP. The information of the Andersons patent is as follows:

King Charles the Second, the 12th of May, 1671. Granted a Patent to Andrew Anderson deceased, and his Assigness, to be His Majesties Printer in Scotland, with the Sole Power of Printing Bibles, New Testaments, all Acts of Parliament, and everything Published by Authority, for and during the Term of Forty one Years. (Baskett 1)

Anderson and Campbell were also “‘Masters Directors and Regulators of his Majesties office of Printing’ with power to police imports of books within the gift, to prevent printers setting up who had not served the appropriate apprenticeship to the art, and, subject to the Privy Council, had the ‘privilege of secluding and debarring all others . . . [of the] freedoms and immunities’ of trade” (137). Anderson was granted this position under Charles II, but the Andersons’ forty-one year patent remained through the reign of James VI of Scotland and II in England (1685–1688), Mary II (1689–1694), William II in Scotland and III in England (1689–1702), and Anne, Queen of Great Britain (1702–1714).

The Anderson patent was cause for suspicion due to the length and “wide-ranging supervisory powers . . . [that] had no precedent in Scottish book history” (Mann 137). During the reign of James I, specifically between 1616 and 1620, the King’s and Queen’s Printer position in England was transferred from Robert Barker to John Bill and, finally, to Bonham Norton (Wakely and Rees 468). With Anderson’s patent, on the other hand, the position was maintained by Andrew Anderson and Campbell alone for their entire forty-one year allotment. Previous Royal Printers relied on each other for help and money, often joining forces and working together (Wakely and Rees 468). In fact, Barker, Bill, and Norton worked together despite competing against each other for the King’s and Queen’s Printer position (Wakely and Rees 468). Their teamwork may have been due to the Stationers’ Company of England, which Mann highlights as inspiration for Scotland and their desire to establish a similar “society of printers” (Wakely and Rees 137); as Ian Gadd explains, the Stationers’ Company of England was a “Guild of Stationers” who were “secured from outside competition” (Gadd). Thus, while the print trade in England was not without its own conflict, it held a different set of standards for their stationers, which Scotland sought to mirror.

While Barker, Bill, and Norton relied on each other for support, Campbell created a network of people through apprentices. Apprentices were used to train new people who may work their way up into a senior position, which “afforded opportunities for patronage or for establishing consolidating networks for obligation” (60). Agnes Campbell successfully networked her business in this fashion, and in just two years following Anderson's death she had “no less than sixteen apprentices” (Mann 13). These apprentices allowed her to grow her own business and teach her trade to up and coming printers in Edinburgh.

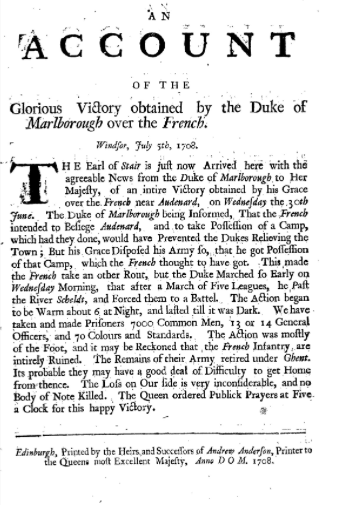

The majority of Campbell’s publications that I have researched have been political materials that the King or Queen wanted to be documented, such as An Account of the Glorious Victory obtained by the Duke of Marlborough over the French (1708). Political materials were a common publication for the King’s and Queen’s Printer, and would often be printed with short notice (Wakely and Rees 140). Royal proclamations specifically were quite short and followed a typical formula, ranging from one to three folio sheets printed on one side only (140–41). Many of Campbell’s records in the ESTC are one page with a similar title and short paragraph below; this common format may have allowed them to print these works more efficiently. While we have no documentation of Campbell’s print runs during her time as the King’s and Queen’s Printer that might provide a sense of just how many copies Campbell was producing, Wakely and Rees documented the print run for Robert Barker, the King’s Printer in London under James I, and he printed anywhere from 500 to 1300 copies of royal proclamations (142).

Figure 3. Copy of an Act for securing the true Protestant religion, and Presbyterian government. ECCO.

Campbell also printed religious texts, and most particularly the Bible. She printed editions of the Bible and distributed them around Scotland and, up until 1681 when it was protested, England (Mann 139). This was a large source of money for Campbell; she printed at least three editions in 1679, 1673, and 1688 (Anderson 2). It is not stated how many Bibles were printed in each print run; however, in relation to Barker, Bill, and Norton’s print run of the Bible in London, Wakely and Rees note that “as monopolists the King’s Printers could not afford to run out of stock [of the Bible]. They had to be ready to supply the market but they also had to ensure that they did not lock up too much capital in wares waiting for customers” (166). Considering that Campbell was the sole printer of Bibles in Scotland, she would have understood the daily market and sales of the Bible and printed accordingly (166). She also printed many religious texts outside of the Bible, which were often related to reinforcing religious beliefs, such as the Act for securing the true Protestant religion, and Presbyterian government (1702).

While working as the King’s and Queen’s Printer was a large income for Campbell, she also worked as a book merchant in the years following her husband's death. Mann explains that “her printing and paper supply business had become the focal point for a large trading zone beyond Edinburgh, covering all the burghs of Scotland and reaching into Ireland. Stock and paper were supplied to the printers of Glasgow, Aberdeen, and Belfast, and books to the booksellers of Londonderry, Belfast, Inverness, Dundee, Aberdeen, Glasgow, Kilmarnock, Dumfries, Newcasde and many other centres” (133–34). Mann adds that Campbell was also their paper provider; she was not only loaning money and obtaining interest, but she was making that money back immediately through her paper sales (134). Her immense wealth is attributed to her “activities as a paper wholesaler - she held over £3000 worth of paper stock in 1716 - . . . but the key explanation was her wide geographical network of commercial customers and agents” (Mann 134). She had a large network of people to rely on, which is difficult to express in the WPHP database. Her networking was a significant aspect of her wealth, but is not as easily captured in our data as we do not collect the role of paper sellers. Thus, all of these business endeavours not only led to her success, but her ability to stand out and be remembered amongst the many male printers and publishers in Scotland. She was not only a woman printing for the King or Queen, she was a successful and wealthy businesswoman who deviated from her husband’s legacy and worked her way up the market.

However, while her legacy is one of success, her business was constantly being targeted and attacked by men who wanted to take over the lucrative position of the King’s or Queen’s Printer. In A brief reply to the letter from Edinburgh, relating to the case of Mrs. Anderson, Her Majesty’s printer in Scotland (1711/12), that is likely authored and printed by Campbell, she makes these attacks known and outlines exactly what her rivals, James Watson and Robert Freebairn, did to tarnish her name. She names them explicitly, writing, “Mr. Freebairn knowing his Case could not otherwise be supported, carryed it on by heaping Slanders and abominable Forgeries, and suggesting infinite Scandalous Things upon Mrs. Anderson, both as to her Employment, her Principles, and the Management of her Affairs” (1).

Figure 4. Title page from A Brief Reply to the Letter from Edinburgh, Relating to the Case of Mrs. Anderson, Her Majesty's Printer in Scotland. Google Books.

Before March 1711, when Watson and Freebairn were to petition for the next King’s and Queen’s patent, they began to attack Campbell’s past work, attempting to permanently destroy her reputation. For example, they charged her with a purposeful error in her 1679 printing of the Bible. They believed that she “printed the Word ye for we … to support Presbyterian Principles” (3). Campbell defends her business, stating that their charge was “an abhorr’d Forgery and Cheat . . . by the same Party Malice that now rages” (3). Further, Watson and Freebairn switched the title page from Campbell’s Bible to a Dutch version, so that they “might load Mrs. Anderson’s with the Errors of a Foreign Impression” (5). Campbell’s entire career was under threat by Watson and Freebairn, who believed that the way to become the King’s or Queen’s Printer was by destroying the name of the current one. However, Campbell begins her Brief Reply with a statement of confidence:

Mrs. Anderson by her Agent here, defended herself against those Bullets shot in the Dark, as well as she might, and had the happiness to detect and expose some of those Slanders, very much to the Satisfaction of some Persons of Honour, who express’d their just Detestation of the Practice, as well as their Resentment at the Attempt made by Mr. Freebairn. (1)

While none of these charges held any legal merit and Campbell confidently rebuffed them, such a response also demonstrates that she was concerned with the consequences of their slander on her reputation, and the future of her printing press.

This Brief Reply was printed after the expiration of Campbell’s patent as an attempt to repair her reputation by publicly challenging the attacks of Watson, Freebairn, and other printers in Edinburgh. Campbell herself notes that while people were inclined to believe her story, her patent was over with no opportunity to be renewed, and she had lost the public’s interest in her: “those Prejudices influenc’d the Publick, and has procur’d Mrs. Anderson to be Condemn’d unheard; The Priviledges, which she has to general Satisfaction so long enjoy’d, and with great Charge and unwearied Pains improv’d, given from her, and Mr. Freebairn to be Constituted in her stead” (2). Indeed, considering that she was no longer their King’s or Queen’s Printer, the future of her business was of little consequence to them. Thus, Campbell printed this Brief Reply in order to share her story and convince the public that her name and business was well established and transpired under proper circumstances.

But this was not, fortunately, where Campbell’s business met its end. In 1712, she was chosen to be the new printer to the Kirk, or the Church, of Scotland. In this position, she was permitted to print supplemental religious texts but not the Bible, as that was reserved for the new King’s and Queen’s printer (Mann 140). She flouted this law, however, and in 1713, was fined £500 sterling for continuing to print Bibles and other government papers (140). As mentioned above, Campbell was quite wealthy by this time and £500 sterling was not a career-ending fine. She paid it, and continued to work in her new position as the Kirk printer, foregoing the illegal printing of Bibles and instead producing the allowed supplemental religious documents, such as Advice to communicants, for necessary preparation, and profitable improvement of the great and comfortable ordinance of the Lord’s Supper: that therein true spiritual communion with Christ may be obtained, and the eternal enjoyment of God sealed (1714).

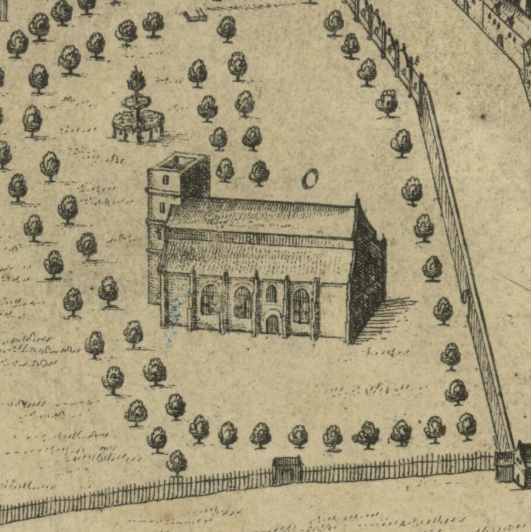

Figure 5. Greyfriars Kirk, 1647. Wikipedia.

Campbell was unable to enjoy her position for long, as she died in 1716 on the 24th of July with a fortune of £78,197 Scottish pounds for her children (ODNB). She was buried at Greyfriars Churchyard in Edinburgh three days later. Her business was passed down to her daughters and their husbands—the newest set of heirs and successors of Andrew Anderson. Very little information is recorded about their family business, but Campbell’s daughters, notably Elizabeth and Issobell Anderson, maintained the role of printer to the Kirk until around 1726. It is possible that Elizabeth and Issobell were involved before their mother passed away; when Campbell was charged and fined for illegally printing Bibles, the decree states that the Bibles were “printed by the said Agnes Campbell, her daughters, grandchildren, and the husbands as married” (Mann 135). Elizabeth and Issobell Anderson are scarcely documented, likely because they did not hold a prestigious position like their mother. The Anderson family history reveals the gaps missing within women’s histories and the unfortunate realities of women’s erasure. While Campbell is well-documented and significant to the history of Scotland’s book trade due to her role as King’s and Queen’s Printer, her daughters and the information Campbell passed down was forgotten.

WPHP Records Referenced

Campbell, Agnes (person)

Agnes Campbell (firm)

An Account of the Glorious Victory obtained by the Duke of Marlborough over the French (title, first edition)

Act for securing the true Protestant religion, and Presbyterian government (title, first edition)

A brief reply to the letter from Edinburgh, relating to the case of Mrs. Anderson, Her Majesty’s printer in Scotland (title, first edition)

Anderson, Elizabeth (person)

Anderson, Issobell (person)

Elizabeth and Issobell Anderson (firm)

Works Cited

Anderson, Agnes. “A Brief Reply to the Letter from Edinburgh, Relating to the Case of Mrs. Anderson, Her Majesty’s Printer in Scotland.” Heirs and Successors of Andrew Anderson, 1711 or 1712.

Baskett, John. “John Baskett, Agnes and Elizabeth Hamiltons, Grandchildren to the Deceased Andrew Anderson, His Majesties Printer, and Archibald Campbell Husband to the Said Agnes, and Patrick Alexander Husband to the Said Elizabeth, for Their Interests, and Mr. John Campbell His Majesties Printers in Scotland, Appellants. James Watson Respondent. The Appellant's Case.” 1718.

Ewan, Elizabeth, and Rose Pipes, eds. “C.” The New Biographical Dictionary of Scottish Women, 2nd ed., Edinburgh UP, 2017, pp. 66–107.

Fox, Adam. “‘Little Story Books’ and ‘Small Pamphlets’ in Edinburgh, 1680-1760: The Making of the Scottish Chapbook.” The Scottish Historical Review, vol. 92, no. 235, 2013, pp. 207–30.

Gadd, Ian. “The Stationers’ Company.” Literary Print Culture: The Stationers' Company Archive, 1554–2007. https://www-literaryprintculture-amdigital-co-uk.proxy.lib.sfu.ca/Introduction/StationersCompany

Mann, Alistair. “Book Commerce, Litigation and the Art of Monopoly: The Case of Agnes Campbell, Royal Printer, 1676-1712.” Scottish Economic & Social History, 1998, pp. 132–156.

Mann, Alistair. “Campbell [Married names Anderson, Telfer], Agnes (1736-1716), printer and book merchant burgh and university printer.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford UP, 2004, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/66354.

Wakely, Maria, and Graham Rees. “Folios Fit for a King: James I, John Bill, and the King’s Printers, 1616–1620.” Huntington Library Quarterly, vol. 68, no. 3, 2005, pp. 467–95.

Wakely, Maria, and Graham Rees. Publishing, Politics, and Culture: The King’s Printers in the Reign of James I and VI. Oxford UP, 2010.