This post is part of our Down the Rabbit Hole: Researching Women in the Book Trades Spotlight Series, which will run through August 2022. This series seeks to make transparent some of our team’s research processes, evidential challenges, and editorial choices while finding and creating data for women in the book trades.

Authored by: Kate Moffatt

Edited by: Michelle Levy and Kandice Sharren

Submitted on: 08/01/2022

Citation: Moffatt, Kate. “Down the Rabbit Hole: Researching Women in the Book Trades” The Women’s Print History Project, 1 August 2022, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/112.

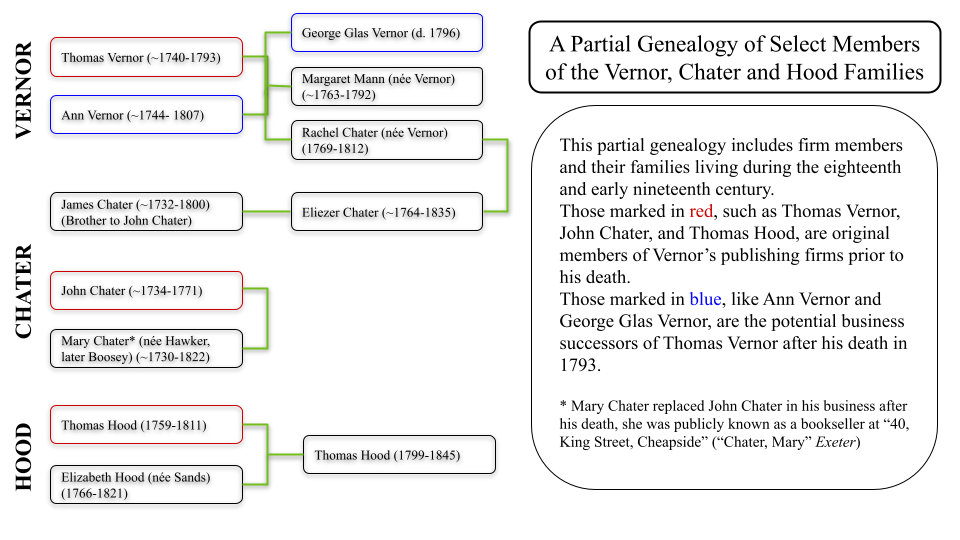

Figure 1. “A partial genealogy of select members of the Vernor, Chater, and Hood families.” Belle Eist, 2022.

Figure 1. “A partial genealogy of select members of the Vernor, Chater, and Hood families.” Belle Eist, 2022.

At the time of this August 2022 Spotlight Series, the WPHP has more than 22,000 titles; 14,000 of those have been researched, edited and verified and are visible to the public. Of these 14,000 titles, just over 2,100 were published, printed, or sold by a firm run by a woman. But these numbers are far from complete or representative of the number of titles women in the book trades produced during the period our database covers, 1700 to 1836, and there are a few reasons for this.

First, the number of title records in the WPHP is always in flux: as we continue checking titles (like those from our recent inclusion of books from the American Antiquarian Society, which we are in the process of verifying for our title records) we often find further new editions to add.

Second, finding women in the book trades presents numerous obstacles. Because firms of the period are not infrequently listed in imprints and colophons with only an initial or a last name to distinguish them from their peers, discovering the gender of, for example, “A. Reilly,” (Alice Reilly, Dublin printer) requires additional research in firm-specific resources like the Exeter Working Papers, British Book Trade Index, Scottish Book Trade Index, or Dictionary of Working Members of the Dublin Book Trade. And many other women do not appear in imprints and colophons at all, with evidence of their involvement in a firm—including running it—at best hidden in the records of their male relatives or associates, who are often far more visible in our resources.

And third, our database seeks to capture all books that a woman helped to produce between 1700 and 1836, and this includes works published, printed, or sold by a woman. So when we do find a woman-run firm, we want to include in the database all works that she published, printed, or sold—something we do not do for firms in the WPHP that are run solely by men. As it turns out, some of these women were quite prolific, and have more than a thousand titles attached to them in sources like the ESTC. In addition to some of the women we have already identified as being this productive—including a number we cover in this Series, like Ann Vernor, Anne Dodd, and Agnes Campbell—we are constantly discovering more women in the trades with extensive catalogues. The volume of labour required to find women in the trades, and then bring all of their works into the WPHP is, quite frankly, massive; and so the extent to which we are capturing or not capturing data for women publishers, printers, and booksellers in the WPHP is unknown but certainly sizable, and is something we are working to correct. As with our initial underestimates about the quantity of books authored and otherwise contributed to by women, we find that when we start looking for books made by women, the evidence quickly mounts and becomes overwhelming.

Our Down the Rabbit Hole: Researching Women in the Book Trades Spotlight Series will introduce a number of women-run firms included in the WPHP, and in the process of doing so, seeks to make transparent some of the work that we do to recover and include them, the editing choices that must be made, and the particular challenges we face.

On August 5, Kate Ozment’s Spotlight, “What Does it Mean to Publish? A Messy Accounting of Anne Dodd,” takes us into the early eighteenth century with Anne Dodd to think about the ways in which definitions of roles in the book trades—publisher, bookseller, printer—were not as static as they may now appear, and indeed meant something quite different than they did in the later eighteenth century.

On August 12, Sara Penn will untangle the publications, businesses and rivalries of the women in the Farley family in Bristol—Elizabeth Farley, Sarah Farley, and Hester Farley—in “The Farley Family, their Feud, and the Bristol Print Trade.”

On August 19, we’ll delve into the position of the “King’s and Queen’s Printer” in Scotland with Julianna Wagar’s Spotlight "A Royal Printer: Agnes Campbell in Scotland's Book Trade" on Agnes Campbell, Lady Roseburn, the successful business woman behind the “Heirs and Successors of Andrew Anderson” imprint.

On August 26, Amanda Law’s Spotlight, “Printed (Bound, Published, and Sold) by Jane Aitken,” explores the findings that can be made by studying imprints at scale. What do we learn when we examine hundreds of imprints—the very kind of research the WPHP was designed to facilitate?

On September 2, Belle Eist will take us deep into the research rabbit hole of discovering Ann Vernor’s identity and involvement in the Vernor and Hood, and Vernor, Hood and Sharpe firms with “Hidden in the Imprints: Introducing Ann Vernor, Bookseller and Publisher, Active 1793–1807.”