This post is part of our Down the Rabbit Hole: Researching Women in the Book Trades Spotlight Series, which will run through August 2022. This series seeks to make transparent some of the processes, challenges, and editorial choices our team has to make while falling down the inevitable rabbit holes involved in finding, and creating data for, women in the book trades.

Authored by: Sara Penn

Edited by: Michelle Levy, Kate Moffatt, and Kandice Sharren

Submitted on: 08/12/2022

Citation: Penn, Sara. "The Farley Family, their Feud, and the Bristol Print Trade." The Women's Print History Project, 12 August 2022, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/113.

Figure 1. Contents of Sarah Farley’s Bristol Journal, 1777. British Library.

Many of the women in the WPHP, including Ann Sancho, Ann Lemoine, and Sarah Belzoni, to name a few, have been recovered because of scholarship on the work of their male associates and relations. More often than not, we find ourselves sifting through the biographical entries of men from our growing list of Sources trying to pin down the presence of the women so often mentioned in passing (if at all).

While recovering Elizabeth, Sarah, and Hester Farley as three Bristol-based publishers, printers, and booksellers generally found alongside a larger network of Farley men in the same trades, their contributions as individuals can also be traced to a fuller extent through specific print genres: newspapers and journals. My literary excavation of the Farleys began when I was offered the task of spotlighting Sarah Farley from the WPHP Project Manager and firms expert Kate Moffatt who had recently encountered her entry in the British Book Trade Index (BBTI). Kate noticed that the BBTI listed Sarah as a possible cousin to Hester Farley—a familial tie confirmed by Victoria E.M. Gardner—piquing our interest. A further dive into the BBTI, ODNB, and even Wikipedia led me to Elizabeth Farley, aunt to Sarah and mother to Hester, who is briefly referenced as “taking over [her husband’s] newspaper” in the combined ODNB entry of the Farley men. Scholarship on Bristol-based newspapers and women’s labour aside from these sources provides a more vibrant story of the Farley women, in part due to their familial prominence, generational feuding, and, in Sarah’s case in particular, impact on the trade.

As the family tree I have created in figure 2 shows, the history of Elizabeth, Sarah, and Hester Farley can be traced back to their grandfather, Samuel Farley I. In founding what would become the Farley's Exeter Journal in 1723 and the Farley’s Bristol Newspaper in 1725, he was “the first member of the family to be active in the newspaper trade” (ODNB). Samuel had three sons that would follow him in the family printing business: Samuel II, Edward II, and Felix. Samuel II and Edward took over the Bristol Newspaper and the Exeter Journal, respectively, after Samuel I died in 1730.

The Farley men were primarily known for “developing a newspaper press that became highly politicized in the south-west compared with local newspapers published in most other regions of eighteenth-century England” (ODNB). Although the Farleys were respected printers in their time, their familial history was bitter and complex. While Samuel II and Edward seemed to manage different branches of their family newspaper harmoniously, Samuel II and Felix’s relationship did not follow suit. In 1734 Samuel II changed the name of the family newspaper to Sam. Farley’s Bristol Newspaper while Felix established his own journal, also in Bristol. Their businesses were initially amicable despite their opposition and the brothers even formed a partnership from 1737 to 1741. According to the ODNB, Samuel II modified the newspaper title to the Farley’s Bristol Journal “probably to reflect the partnership between [them].”

After a decade of relocating, separation, and reuniting, their partnership quickly dissolved, and by 1752 the brothers “became rivals in the trade” (Latimer 292). Felix broke off from the business to initiate a rival journal under his own name, Felix Farley’s Bristol Journal in Small Street, while Samuel II continued to print Farley’s Bristol Journal, renamed the Bristol Journal, down the block in Castle Street. Felix wished to feature advertisements more prominently in his newspaper to the point where he, as John Latimer notes, “assured advertisers that his new Journal would extend farther than any other yet published in the city” (292). Although we may never know what started the quarrel between the brothers, it changed the face of the family forever.

Figure 2. This Farley family tree amalgamates historical information drawn from the ODNB, Victoria E.M. Gardner’s “Appendix” in The Business of News in England, 1760–1820, and the “Biographical Appendix” in The Letters of Charles Wesley. Sara Penn, 2022.

When the estranged brothers died in 1753, both left their newspapers to their female next of kin. As Hannah Barker summarizes, “Felix left his business to his wife Elizabeth, while Samuel was succeeded by his niece, Sarah” (94). But it was not solely the newspaper business that was maintained by Elizabeth, Sarah, and later Elizabeth’s daughter and Sarah’s cousin, Hester; it appears that the tensions between the two businesses were also carried throughout three generations. “The two Farley newspapers,” Barker adds, “were run by women for the next twenty years, and continued to display a fierce commercial rivalry. As [John Latimer] noted, ‘neither of the papers showed any lack of vigour when conducted by the ladies’” (94).

Elizabeth, Sarah, and Hester primarily produced monthly newspapers and periodicals, genres that the WPHP does not include. Despite their newspaper specialty, each Farley woman contributed to a number of books, poems, and broadsides as printers, publishers, and booksellers during their takeover, which we do include. A closer look at the productions of each of the Farleys reveals that their histories are very much intertwined as a result of the antagonism of their businesses.

The new matriarch of the family, Elizabeth Farley I (1714–1779), acquired Felix Farley’s Bristol Journal, which she operated from 1753 to 1773 in Shakespear’s Head, Small Street, Bristol. She briefly partnered with her son, Samuel III, from 1753 to 1756 before he left to start his own newspaper in Bath. He returned after this endeavour failed and joined his mother once more from 1758 to 1760. Thomas Cooking was contracted as a partner in 1767 before taking over from Elizabeth fully from 1773 to 1787, when he died. According to an index of British newspapers, Felix Farley’s Bristol Journal eventually morphed into the Bristol Times and Mirror, among other titles, before its last issue in 1912 (“The Bristol Times and Mirror” 60).

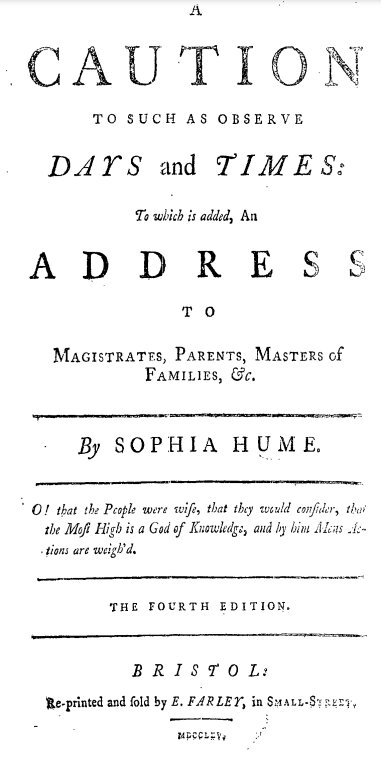

As Bristol historian Madge Dresser writes, Elizabeth printed “at least 23 Methodist books [,] hymns and pamphlets between 1755 and 1765 including sermons by John Wesley and hymns by his brother Charles” (18). According to the WPHP title records, she also printed and sold at least one edition of family friend Charles Wesley’s Hymns and Sacred Poems and at least two editions of Sophia Hume’s A caution to such as observe days and times: to which is added, an address to magistrates, parents, masters of families, &c. (figure 3). She worked semi-regularly with booksellers James Dodsley, George Kearsley, Thomas Davies, and John Almon, and collaborated with publisher John Walter at least once in 1767. It is unclear if Elizabeth operated from her own shop because her imprints do not include an address, although it is likely she continued to operate from Felix’s premises in Small Street.

Out of Elizabeth’s three children—Elizabeth II, Hester, and Samuel III—only her firstborn Elizabeth II seems to have removed herself entirely from the newspaper trade. Her niece-in-law Sarah, however, maintained the family legacy with flourish, while Hester joined the business for only a brief period of time before leaving behind the print trade.

Figure 3. Fourth edition title page from a religious work printed and sold by Elizabeth Farley. ECCO.

Sarah Farley (d. 1774) is perhaps the most well-documented of the three Farley women. As the daughter of Edward and the niece of Samuel Farley II, Sarah managed the Bristol Journal from 1753 to 1774, around the same time that Elizabeth took over from Felix. Sarah’s brother Mark also joined the business until 1762. She initially ran the journal from Small Street (although there are no WPHP title records of this location) before relocating to Castle-Green.

Sarah also continued to uphold the rivalry between her uncles. In the same year of Samuel II’s death in 1753, she “announced that [she would] give greater publicity to advertisements [and] they would be posted ‘in the most public places in the city’” (Latimer 293). As Sarah herself put it, she particularly targeted “the Exchange and the Tolzey, in the marketplace, and on the several city gates, and by men who carry the Journal into the country by Monday (two days after publication) to fix them up in the cities of Bath and Wells, and all the market towns” (qt. in Latimer 293). In other words, she not only took it upon herself to include more advertisements than her ‘rival’ uncle Felix wished, but she also devised a careful plan to scatter them as far across southern England as she could.

It is unclear how successful Sarah’s plan was, but it certainly did not go unnoticed by Elizabeth, who also made a great effort to carry out Felix’s wishes. In 1755, Elizabeth tricked Sarah “with publishing articles a month old” (Latimer 293), a gesture which her niece did not retaliate. Indeed, Sarah made an effort to keep the rivalry between the business only, while Elizabeth took a more personal approach and did not hesitate to directly vilify other papers and peoples in the press. In the same year, for example, Elizabeth publicly deemed a rival journal, the Intelligencer, as a “virulent party paper” and later “described the editor of the Bristol Chronicle as inauthentic and hasty” (Latimer 293). A fiery Tory supporter, she also launched a “campaign against the naturalization of Jews” and “also pursued an extravagantly-worded campaign against Whig corruption” during her tenure (Dresser 18). As a Quaker—likely with Whig leanings—Sarah did not share her aunt’s political values, a factor that likely contributed to their long-standing rivalry.

Apart from the Bristol Journal, Sarah printed, published, and sold a variety of books including elegies, poems, dramas, and tragedies. As the WPHP entries show, she was particularly active in her final years in 1773 and 1774. Sarah was also remembered for her kind nature and “superior talents” in her time; as diarist Sarah Fox (née Champion) writes:

[Sarah] had been to us a near and very kind neighbour, and her benevolence and universal acquaintance rendered her removal a great loss and generally regretted. Men of distinguished abilities, of all ranks and descriptions, resorted to her house and were fond of her conversation. She succeeded her father or her uncle in the printing business, and it was not by education, but by superior talents that she emerged from obscurity. The poor bewailed her death as the loss of a benefactor. She was a single woman, but was at this time earnestly solicited to become a wife by her neighbour [the merchant] Wm. Green, whose entreaties had hitherto been unavailing. (qt. in Dresser 19)

According to the ODNB entry for the Farley family, “She never married but was prominent in local literary circles, Hannah More being among her friends.” She collaborated with Thomas Cadell, Thomas Carnan and Francis Newberry, and W. Frederick in her later career, and, less occasionally, with the likes of Mary Deverall. She also published several editions of a pastoral drama “By a Young Lady.”

Hester Farley (1750–1806) inherited the Bristol Journal from her cousin Sarah in 1774. She seemed to have little interest in the newspaper since one year later she later sold the business to her brother-in-law, Charles Nelson, husband of Elizabeth Farley II, and George and William Routh. Nelson and the Routh brothers, known as Rouths and Company, renamed the newspaper Sarah Farley’s Bristol Journal in 1777, clearly seeking to exploit Sarah’s name and influence (figure 4). It is unclear why Hester maintained the family business for so short a time, although Sarah likely bequeathed the Bristol Journal to Hester because she “was a friend of Susannah Wesley, Charles Wesley’s daughter, [and] seems have ended up as the second wife of Thomas Rutter a local Quaker brush manufacturer and preacher who had been a visitor to [Sarah’s] aunt’s home” (Dresser 20). The Farleys were close friends with the prominent and vocally religious Wesley family throughout their newspaper reign, and their recoverability is likely aided by their ties with them.

Figure 4. 9 August 1777 edition of Sarah Farley’s Bristol Journal as printed by the Routh brothers. British Library.

While Sarah seemingly ended the Farley feud by bequeathing the newspaper to Hester, there was no shortage of animosity between other members of the print trade. As Latimer summarizes, “Sarah’s former foreman and clerk, annoyed at not being chosen as her successors, set up Bonner and Middleton’s Bristol Journal in August, 1774, so that there were three local papers [Bristol Journals] of the same name” (293). Sarah Farley’s Bristol Journal eventually came to a close at the end of the eighteenth century when its new owners could not maintain it.

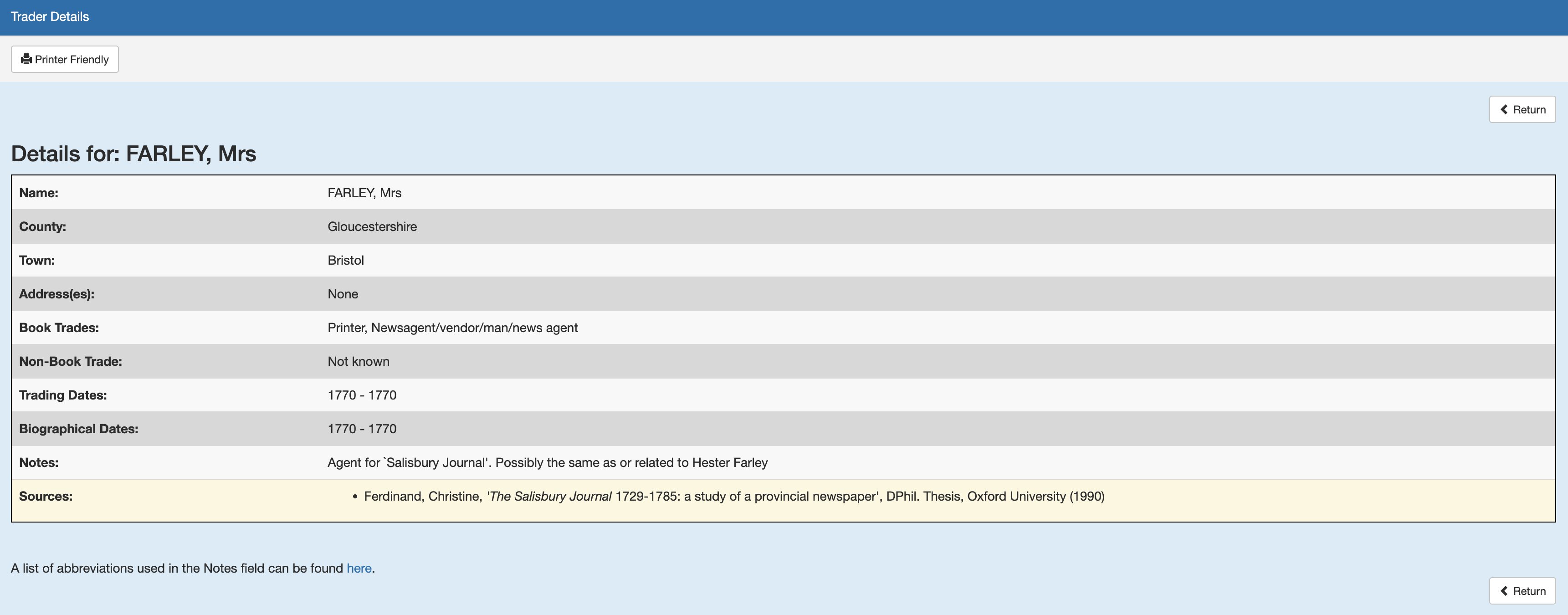

According to a BBTI entry entitled “Mrs. Farley” and a study by C.Y. Ferdinand, Hester was also connected to the Salisbury Journal, a newspaper that Samuel I attempted to establish throughout his early career. However, she only ever contributed to one issue in 1770 before marrying writer Thomas Rutter in 1780 and disappearing from the imprints altogether.

Figure 5. “Mrs Farley” as recorded in the BBTI.

The WPHP includes a Person record called Mrs. Farley, although it is unclear who this elusive figure was as they did not sign the imprints or elsewhere with their first name, and the only title attributed to them is undigitized. As Kate and Kandice discuss in the Season 3, Episode 1 of The WPHP Monthly Mercury, we regularly encounter incomplete forms of attribution that do not fully capture an author’s identity. While there are no records of Elizabeth or Sarah putting pen to paper, there are clues, however, that suggest that Mrs. Farley may be Hester. First, while Hester was as only ever recorded as a printer in her lifetime, she did edit at least one book. For example, she took Thomas’s last name when they married, and, years after his death, edited a collection of his works in 1803 under her married name, “Hester Rutter.” Rather than print and sell the work herself, she collaborated with William Phillips, who undertook these roles. Her editorial note at the end of the collection reveals that her husband was a “tender and affectionate Husband and Father, anxiously concerned that his beloved children might remember their Creator in the days of their youth, and not be ashamed of the cross of Christ” (27). It is unknown how many children they had or what their names were.

It is also entirely possible that Mrs. Farley is a woman unrelated to Hester, Sarah, or Elizabeth. Indeed, the only title attributed to Mrs. Farley in the WPHP is the second edition of Hymns and Reflections, published (possibly) in 1835. If Hester was indeed involved with this book, it is likely a reprint given that she died in 1806. Further, the title was also produced in Birmingham and Hester was not known to live or work outside of Bristol during her lifetime.

While Elizabeth and Sarah are generally identifiable through their family, friends, and the newspaper trades more broadly, the printed traces of Hester’s work are not exposed in the same ways. Given how quickly she severed ties with Sarah Farley’s Bristol Journal and the Salisbury Journal, it is likely that her fleeting participation in the newspaper trade largely affects her recoverability. The Bristol rather than London premises from which the Farley women printed, sold, and published also influences their traceability in the archives.

Largely hidden behind the contributions of their husbands, uncles, and the feuds that separated them, Elizabeth, Sarah, and Hester Farley render visible an enriching Bristol book history that spans twenty years and possibly further. As this spotlight has shown, women were not only active participants in the book trades, but they often undertook more than one role. While sources primarily point to the printing businesses of the Farley men, the Farley women further contributed to the book trade as printers, publishers, booksellers, and in Hester’s case, editors, as well. Alongside the other firms that will be discussed in this spotlight series, the Farleys point us to only a portion of female-run businesses that deserve—and demand—our full attention.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the British Library staff for helping me track down the Farley newspapers.

WPHP Records Referenced

“A Search for Firm Evidence: Uncovering Ann Sancho, Bookseller” (spotlight by Kate Moffatt)

“Ann Lemoine: England’s First Female Chapbook Publisher” (spotlight by Sara Penn)

“Sarah Belzoni’s (Not So) Trifling Account of Women in Egypt, Nubia and Syria” (spotlight by Victoria DeHart)

Sources (Explore Sources)

Spotlighting (spotlights)

Kate Moffatt (Meet Our Team)

British Book Trade Index (source)

Samuel Farley II (firm)

Project Methodology (data model)

Genres (Explore Genres)

Farley, Elizabeth I (firm)

Hymns and Sacred Poems (title)

Hume, Sophia (person)

James Dodsley (firm)

George Kearsley (firm)

Thomas Davies (firm)

John Almon (firm)

John Walter (firm)

Sarah Farley (firm,)

Thomas Cadell (firm)

Thomas Carnan and Francis Newberry (firm)

W. Frederick (firm)

Deverall, Mary (person)

A search after happiness: a pastoral. In three dialogues. By a young lady. (title)

Hester Farley (firm)

Rutter, Thomas (person)

Person (Explore Persons)

Farley, Mrs. (person)

Season 3, Episode 1 (podcast episode)

The WPHP Monthly Mercury (podcast)

Some Account of the Religious Experience and Gospel Labours of Thomas Rutter. (title)

William Phillips (firm)

Hymns and Reflections (title)

Works Cited

Barker, Hannah. “Women, work and the industrial revolution: female involvement in the English printing trades, c. 1700–1840.” Gender in Eighteenth-Century England: Roles, Representations and Responsibilities, edited by Hannah Barker and Elaine Chalus, Longman, 1997, pp. 81–100.

“The Bristol Times and Mirror.” The British Printer: Vol. X–1897. London, p. 60.

Dresser, Madge. “Middling women and work in eighteenth-century Bristol.” University of the West of England: Research Repository, <https://uwe-repository.worktribe.com/output/937808/middling-women-and-work-in-eighteenth-century-bristol>.

Gardner, Victoria E.M. “Appendix.” The Business of News in England, 1760–1820. Palgrave Macmillan, 2016, pp. 166–207.

Latimer, John. The Annals of Bristol in the Eighteenth Century. Printed for the Author, 1893.

Maxted, Ian. "Farley family (per. 1698–1775), printers and publishers." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford UP, 2003, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/64308.

Wesley, Charles. “Biographical Appendix.” The Letters of Charles Wesley: A Critical Edition, with Introduction and Notes: Volume 1, 1728–1756, edited by Gareth Lloyd and Kenneth G. C. Newport, Oxford UP, 2013, pp. 427–51.

Further Reading

Cranfield, Geoffrey Alan. The Development of the Provincial Newspaper 1700–1760. Oxford UP, 1962, pp. 60–61.

Ferdinand, C.Y. “From Newsagent to Reader: Defining Readership.” Benjamin Collins and the Provincial Newspaper Trade in the Eighteenth Century. Oxford UP, 1997, pp. 95–134.

Penny, John. “An Examination of the Eighteenth Century Newspapers of Bristol and Gloucester.” Bristol Past, <http://fishponds.org.uk/brispapr.html>.

Plomer, Henry R. A dictionary of the booksellers and printers who were at work in England, Scotland and Ireland from 1641 to 1667. London, Printed for the Bibliographical Society, 1907.

Sharren, Kandice, and Kate Moffatt. “From Print to Process: Gender, Creative-Adjacent Labour and the Women’s Print History Project.” Women In Print: Distribution, and Consumption: Volume 2, edited by. Helen S. Williams, Peter Lang, 2022.