This post is part of our Down the Rabbit Hole: Researching Women in the Book Trades Spotlight Series, which will run through August 2022. This series seeks to make transparent some of our team’s research processes, evidential challenges, and editorial choices while finding and creating data for women in the book trades.

Authored by: Kate Ozment

Edited by: Michelle Levy, Kate Moffatt, and Kandice Sharren

Submitted on: 08/05/2022

Citation: Ozment, Kate. "What Does it Mean to Publish? A Messy Accounting of Anne Dodd." The Women's Print History Project, 5 August 2022, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/111.

Figure 1. An Image of A Caveat Against the Tories, published 1714. ECCO.

If you search for “A. Dodd” and “Mrs. Dodd” as a publisher in the English Short Title Catalogue, it will return 844 records, ranging from 1712 to 1756. These names denote the careers of two women: Anne Dodd, who lived from 1685 to 1739, and her daughter, also Anne Dodd, who died in 1757. In this spotlight, I will briefly detail the Dodds’ careers as two of the best-known women in the English book trades in the eighteenth century before touching on how their lives and work create some messiness for the contemporary bibliographer trying to code their labour into a database with fixed data fields and user expectations. Hopefully this look at the messy ways we are accounting for the work of the Dodds and their contemporaries like Elizabeth Nutt can make visible the interpretive choices of something that seems quite innocuous: how we characterize the relationship of these women-run firms to the titles they appear on.

Like many women in the English book trades, Anne Dodd Sr. worked with her husband, Nathaniel Dodd, who was also a stationer, from their marriage in 1711 until his death in 1723. While court records indicate that Nathaniel Dodd was involved in running the business, it was almost always Anne Dodd’s name that appeared on imprints, indicating she had substantial control (Treadwell, ODNB). The Dodd family shop at the Peacock near Temple Bar was the “the best-known pamphlet shop in London” (Treadwell, ODNB), although they also sold periodicals, ballads, and a variety of other printed works including poems, plays, and novels. Their investment in cheaper and topical works of politics and satire might (and occasionally did) result in arrests and, consequently, a few stints in prison. Much of what we know about the Dodds is through their relationship to canonical male authors like Alexander Pope, notorious booksellers like Edmund Curll, and the work of book trade historian Michael Treadwell. Treadwell’s work on publishing practices in the early eighteenth century underpins this article significantly, and his research notes are digitized and hosted through Trent University.

Working with the Dodds has a few challenges, some of which the WPHP team are familiar with and some we are grappling with for the first time. The most obvious challenge is one of volume: it will take quite a few hands to account for their nearly 850 records, and that process is ongoing. Secondly, these records are dense as the Dodds relied on extensive networks of tradespeople to publish. These networks are sometimes informally referred to as congers, referencing a specific association that formed in 1719 called The Printing Conger. According to John Nichols, the Conger included publishers like Rebecca Bonwicke, who was of the “respectable” sort (340). While the Dodds were not in the Printing Conger, they did have their own networks which frequently included other women like Elizabeth Nutt and Elizabeth Cooke, as we see with True Character of the Rev. Mr. Whitefield (1739). These associations would offset financial risks, as each member would take part of a run of a periodical, for example. It would also signal to buyers that like your favourite weekly magazine, a title could be had at major pamphlet shops all over town, not just in one place. The challenge for WPHP team members is that every imprint needs multiple firm records, and when we see a “Mrs.” (or a woman’s name) in the imprint we give the person extra attention, so we sometimes spend an hour on a single title.

Figure 2. An image of True Character of the Rev. Mr. Whitefield, printed 1739. ECCO.

The most significant challenge we face, however, is a conceptual one: how to characterize the relationships the Dodds have to the imprint records we are working with. Typically the Dodds use language we associate with retail, or being a bookseller. Booksellers are one of three roles we assign firms in the database; the others are publisher and printer. But there is a separation between what being a bookseller denoted in the 1600s up to around 1760 and what it meant to readers slightly later in the century.

When I first began working with eighteenth-century books, I assumed that publisher meant someone who was responsible for the book financially—this is almost always what is meant in later eighteenth-century imprints, and it is the contemporary meaning, too. Publishers like Penguin or Hachette pay the author, editors, designers, and other staff to produce a book, and in turn they stand to make the most money if the book sells. The distinction between publisher and bookseller, while it could overlap in the later part of the century, nevertheless identifies clearly differentiated roles. In my mind and in the mind of many late eighteenth-century readers, the division of roles would likely be denoted as the following:

Table 1. Late Eighteenth-Century Associations.

| Role | Labour | Language in Imprints |

| Publisher | Finance; wholesale; may also do retail | Printed for; Printed for and Sold by (if also owned shop) |

| Printer | Physical replication; may also do retail | Printed by; Printed by and Sold by (if also owned shop) |

| Bookseller | Retail; wholesale | Sold by; Can be Found at |

Near the end of the century, imprint language—as seen in the right of the table above—indicates with decent reliability who is performing different jobs in the book’s publication process. This is the understanding that the WPHP team uses to help us connect firms to title records. In addition to these examples, we might see alternate financing information such as “Printed for the Author,” which we mark as “self-published.”

However, in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, what labour imprint language signifies is much more difficult to parse with certainty, and the roles we align with responsibilities in a book’s production shift from the divisions in the above chart. The easiest part is identifying printers, whose role is blissfully stable; it signifies the same labour from the 1500s to the early 1900s and only really changes when “printer” begins to stand in as a machine in the twentieth century. Publishers and booksellers are where things get dicey.

According to Treadwell, in the early part of the century, selling and financing were collapsed under a single role: the bookseller. The idea that a publisher was distinct as an entity that “cause[s] books to be printed and distributed for sale” had not yet developed (“London Trade Publishers” 99). Instead, then, those who advertised themselves as booksellers were not just selling books, but “any one who engaged in any one, or any combination, of three activities, now generally separate, which we designate as wholesale and retail bookselling and publishing” (Treadwell, “London Trade Publishers” 99). In addition to selling books as wholesale and retail, booksellers could and often did hold copyright, which was established when a book was registered with the Stationers Company. Authors’ intellectual property rights at this point are vague, as copyright heavily favoured tradespeople until closer to the end of the century (see Ross and Rose). In sum, then, almost everyone on early eighteenth-century imprints would identify as an author, bookseller, or printer.

So, publishers as a concept just didn’t exist yet? That would make this simpler. But of course, there is a small group of people referred to as publishers. They just did not perform the roles described in the above chart of financing books, as that was being done by booksellers. Instead, publishers were in the distribution wing of the book trades and generally did not own copyright (Treadwell, “London Trade Publishers"). They would put their names on imprints and wholesale or retail them, concealing copyright owners and other labourers. Publishers would take on the risk of “owning” an imprint for a fee, and their service included both deliberately obscuring ownership and offering an “established marketing network” (Raven 172). To help keep the distinction straight for modern readers, D. F. McKenzie and subsequent scholars use the phrase trade publisher to characterise this specific function in book trade distribution. I’ll take up that phrasing now to clarify that we’re not talking about general publishing.

Trade publishing is one aspect of distribution, so let’s take a moment to clarify what that means before we go back to the case of the Dodds. Distribution is by far the messiest aspect of the book trades because it functions differently from printers and booksellers who have the Stationers Company, a guild, as oversight. Less oversight for distributors means less documentation, and, Lisa Maruca argues, distribution is the aspect of book trades that is the most permeable to women as a consequence (111). To sell a book, you did not have to have an apprenticeship, nor enough capital to be able to finance a book that might not return profits for years, if ever. Maruca notes that you might not even have to be literate—just enough maths for bookkeeping and the ability to remember what it is you are selling.

Despite scholarship’s overall lesser attention to it, distribution was a very important aspect of the book trades. After all, if your intent is to have the public read a book, it matters quite a bit that the public actually gets its hands on it. While my focus is on distributors who leave their names on imprints since that is what the WPHP tracks, there are far more labourers in distribution (many of them women and children) whose names we do not know because they sold objects without marking them. Sometimes we find them advertising in periodicals in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection or in an aside from another book tradesperson’s records, but more often than not, they are on the fringes of book history. As a great example of this history, see Joad Raymond’s account of mercuries.

Back to the Dodds: as distributors, they would sell books others had printed and financed. Sometimes this involved claiming the book to obscure copyright ownership, or trade publishing, and sometimes they would simply sell a book outright. The Dodds appear in far more search hits in the Burney Newspapers Collection, which records advertisements of book sales, than in the ESTC, which records imprints, so the WPHP is only going to account for a portion of the Dodds’ wider distribution career. Identifying when trade publishers’ imprints signal that they are acting in that role always requires additional research. Here are two examples, both from court cases because additional legal documentation provides confirmation on copyright ownership that is not always possible.

First, we’ll look at (my favourite scandal writer) Delarivier Manley, who wrote the political satire Secret memoirs and manners of several persons of quality, of both sexes. From the new Atalantis, an island in the Mediterranean. John Barber purchased the copyright and published it beginning in 1709, using the trade publishers James Woodward and John Morphew to obfuscate his ownership and legal liability. Barber’s name is nowhere on the imprint, and neither was Manley’s as it was published anonymously.

When the book had its anticipated effect of irritating some rather powerful aristocrats (specifically Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough), Morphew and Woodward were arrested first as their names were on the imprint. Manley and Barber were arrested shortly after, presumably because Woodward and Morphew revealed who owned and wrote the book. Rachel Carnell’s excellent sleuthing located the court records and confirmed Manley and Barber’s ties to the book, not any information on the book itself or other advertisements. (However, I should note that Manley’s authorship had been assumed for a long time due to subsequent publications.)

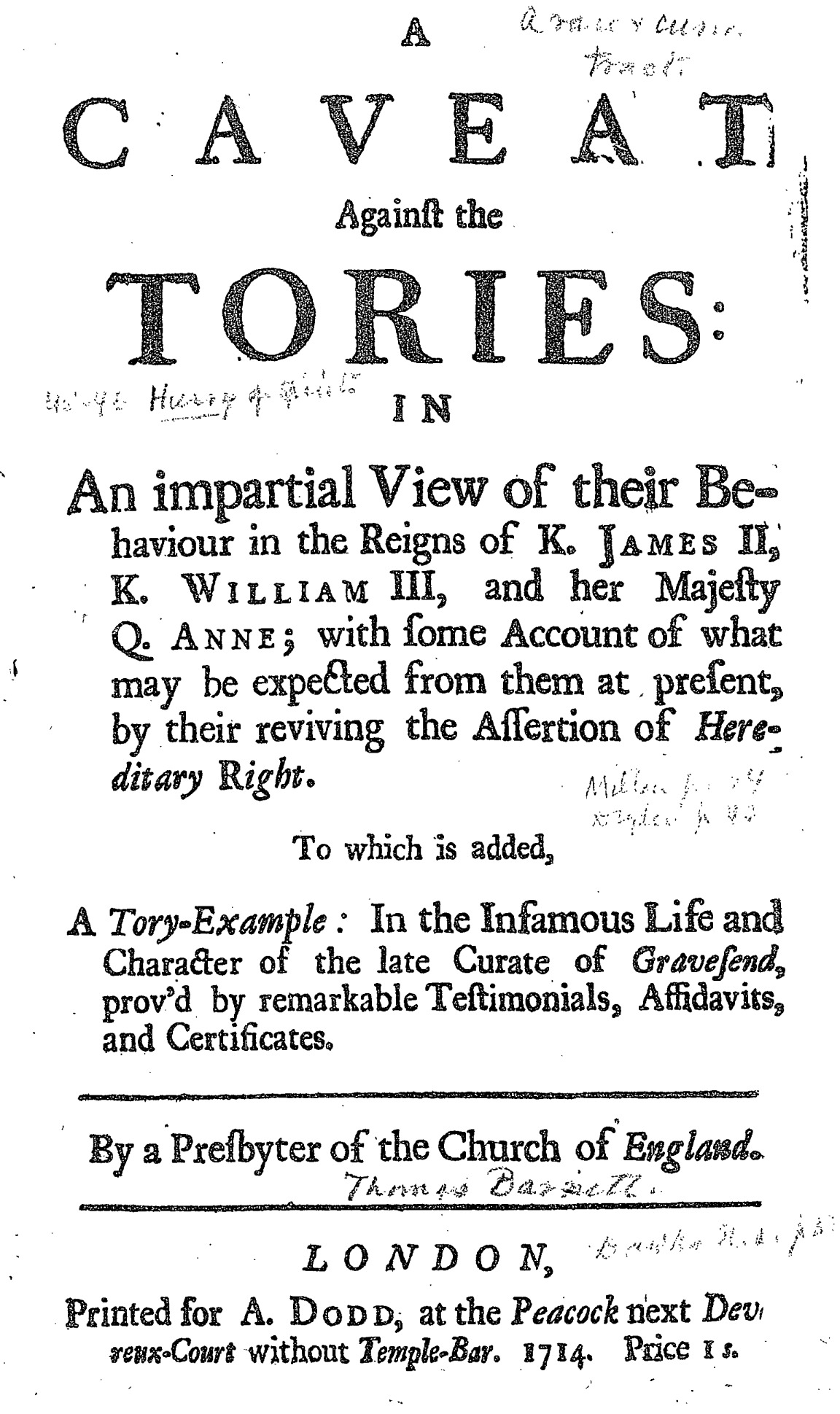

Similarly to Woodward and Morphew, the Dodds’ interactions with the courts illuminate an interesting history of what information imprints convey. The most well-researched incident involved Alexander Pope’s The Dunciad, as its publication history has fascinated more than 200 years of book trade historians and bibliographers. Anne Dodd Sr.’s name appears on initial editions in 1728, although it was James Bettenham who entered the presumed first edition in the Stationers Register (Vander Meulen). I am unable to reliably say whether or not Dodd’s name was used with her knowledge. Scholarship regularly refers to the 1728 Dodd imprints as jokes or “fakes,” which is confusing. Are they fakes because Dodd wasn’t involved? That would seem like a fair word to use, if so, but I have not found satisfactory evidence that Dodd was not the trade publisher.

More often, articles imply that they are fakes because she wasn’t the copyright owner, as Bettenham nominally claimed ownership of the title. These characterizations seem to misunderstand that trade publishing was a common practice that hardly equals the negative association of fakery. For contrast, no one to my knowledge has labelled the Woodward and Morphew imprint a “fake” because Barber owned it (and while I can’t say yet that gender plays a role in that distinction, I would not be surprised if further research uncovers a divide in how trade publishers are characterised along gendered lines). Trade publishing is a convenience for tradespeople and authors who, for many reasons, did not want to publicly own every work they wrote or produced.

In 1729, an equally messy but different edition of The Dunciad also bearing a version of Dodd’s name ended with her in court and gives us some additional perspective. Lawton Gilliver seems to have purchased the copyright to The Dunciad (from who and exactly when, I cannot easily summarise) in 1729 and used his holding to sue other publishers and printers for infringement. The imprint of an accused piracy reads “Printed for A. Dob,” a typo meant to reference Anne Dodd Sr.

Figure 4. An image of Alexander Pope's The Dunciad Variorum, published 1729. ECCO.

Figure 4. An image of Alexander Pope's The Dunciad Variorum, published 1729. ECCO.

Gilliver’s suit included the defendants stating Dodd had no tie to the book: “Anne Dodd neither then had nor now hath any right to Title to the said Copy nor any Share whatsoever in the property thereof and that her name was put to the said Quart Edition of the said Book without her Privity Knowledge or Consent and that she never Sold or Disposed of the said Books” (qtd in Sutherland, 351). Dodd later affirmed this fact with an affidavit but did not elaborate on whether or not she distributed the 1728 editions that also bear her name. While I do hold space for the possibility Dodd may not have been wholly truthful—in this same period, noted political writer Eliza Haywood was arrested for seditious libel and claimed she never wrote anything political (King 1)—if we accept this version of events, Dodd was pulled in for something she did not publish rather than something she did. If she had helped publish a pirated book, like Woodward and Morphew she would have gotten in legal trouble along with the defendants.

Dodd’s reputation as a trade publisher and pamphlet seller made her name currency for scandal literature. If the 1728 imprints are a “fake,” in the sense she wasn’t the trade publisher, it is certainly because she was so ubiquitous that her name was chosen and carried over onto the 1729 edition. But secondly, her disavowal of work on a 1729 edition does not preclude that she acted as trade publisher on the 1728 editions. Publishers distribute one edition of a book but not another with regularity, and one can imagine a plethora of reasons Dodd might want to keep mum unless under oath to respond to the 1728 publications. Why invite trouble by tying oneself to a public scandal? While trade publishing was often innocuous, it did run the risk of arrests and court cases, and Dodd’s tailored response to only the 1729 edition might be evidence of business acumen more than the disavowal of the 1728 editions that it is often read as.

As you can see with these examples, the chart used above to parse imprint language for labour divisions and assign corresponding roles is not a useful way to reflect the relationship of a tradesperson to a title in the early part of the century. Imprints during this period are often misleading, making it appear that books are moving through channels they are not. On top of this, as the example with The Dunciad shows, imprint language is unstable. Trade publishers will use “printed for,” “printed by,” “printed and sold by” and “sold by” indiscriminately, although the last two are the most common, as we see with A Short View of the Conduct of the King of Sweden (1717).

Figure 5. An image of Short View of the Conduct of the King of Sweden, published 1717. ECCO.

Figure 5. An image of Short View of the Conduct of the King of Sweden, published 1717. ECCO.

The comma after “printed” indicates, to me, that the book was printed by an entity purposefully omitted from the imprint and separately sold by Dodd. This is relatively straightforward, but others are not. The Dodds will not infrequently use language like “printed for,” visible on A Caveat Against the Tories (1714). Our above chart would direct us to assign Dodd the role of publisher in the popular sense, as a finance and copyright owner.

However, that is almost certainly not the case here. Treadwell argues that “Printed for” is the least reliable indicator of book trade labour: “the ‘printed for’ form, being the norm, seems to have been resorted to automatically by the printer in the absence of specific directions to the contrary. Accordingly . . . nothing can safely be concluded from the form ‘printed for’ in the absence of other evidence” (“London Trade Publishers” 116). If we accept Treadwell’s arguments, then, Dodd likely owned no copyright in either of these examples and was acting as a distributor. This is part of a constellation of reasons that imprint language is an unreliable indicator of labour roles in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. While I have offered two accounts where court cases clarify ownership to some degree, since suits are relatively rare and are not always conclusive, we will never know for certain the exact relationship of the Dodds to most of these titles, other than they were involved in some way—even if only by reputation.

With all this in mind, you can imagine the difficulty I faced when asked what role I should choose to connect the Dodds to their imprints. Available roles are bookseller, publisher, and printer, and these have been applied previously in the WPHP with a late century understanding of what labour they signify since the first data included is from 1750 to 1830. However, as you now know, in the early part of the century imprint language was applied differently and inconsistently. An early eighteenth-century chart would look something like this:

Table 2. Early Eighteenth-Century Associations.

| Role | Labour | Language in Imprints |

| Bookseller | Finance; wholesale; retail | Printed for; Printed for and Sold By |

| Printer | Physical replication; may also do retail | Printed by; Printed by and Sold by (if also owned a shop) |

| Trade Publisher | Claims imprints; wholesale; retail | Printed for; Printed for and Sold by; Printed by; Printed by and Sold by; Sold by; Can be Found at |

| Mercury or Other Distributors | Retail | Sold by; Can be Found at; no marks on imprint |

This is not exactly clear cut for editors, much less users. Since users are searching for a set of roles that is not differentiated by decade, editors have to be consistent with how they are used across the database. The typical user for the WPHP is likely going to have late century assumptions since those are more or less the same as our current usages.

All projects must balance the expectations of the user and findability with precision and historical accuracy, so with the Dodds’ imprints (and those of other trade publishers), we have chosen to go with clarity for users and have indicated their relationship to imprints based on our contemporary understandings rather than early eighteenth-century ones. That is, when we parse imprints, we use divisions of labour in the first chart rather than the second chart. The bibliographer and book trade historian within me somewhat bristles at this decision. I’m marking Dodd rather often as a bookseller when she was pointedly not characterized as such in the period, and when I do mark her as a publisher, users understand it as a financier not a distributor. But, there is no perfect data model that can capture every nuance (although I dream). And as the second chart indicates, the slipperiness of imprints in the early part of the century means that there is not a simple solution to offer, nor existing research to back up every deviation from typical conceptions of what imprint language indicates.

As I work through hundreds of imprints associated with the Dodds and other women distributors from the early part of the century, quite a bit of my work has been unpacking how they are poorly characterized in book trade scholarship that heavily favours male copyright owners as the most valuable subjects. Maruca quite aptly argues that it is because distribution was more permeable to women and did not signal property ownership that it has been not taken as seriously by book trade historians who have largely focused on copyright and its holders (108–11). My short exposition of scholarship on the 1728 Dunciad editions is only one example I have run across. While Treadwell has arguably done more work on Anne Dodd Sr. and other trade publishers than any other scholar, he nevertheless argues that her “success and renown should not, however, be confused with real importance in the publishing world, for she owned no copyrights and merely distributed those papers on which her name appeared” (ODNB).

Other scholars have pushed back against such remarks as biased and questioned why copyright is our measure of importance and significance. As Maruca and Raymond have identified, distribution may be gendered feminine, but arguably it is this very gendering—the fact that it is an activity associated with women—that has resulted in its diminishment in their time and ours. Why should “real importance in the publishing world” be associated exclusively with ownership of copyright? What is inherently unimportant about distribution as the means by which books, and the ideas they contain, circulate? Dodd was the public face of many of these books, and we should not simply dismiss that as lesser because she was not making as much money off the book as someone else, especially in a period that was dubious at best about women’s right to own money and property and locked copyright into roles that required formal apprenticeship. While there are many factors that go into evaluating something as less significant, we cannot disregard that gender and class have played into the lesser status that trade publishers, mercuries, and their associates have been accorded in book trade history.

Hopefully, by gathering more data on the Dodds, Elizabeth Nutt, Elizabeth Cooke, Sarah Popping, and the other women trade publishers, we can reconsider the extent of their roles in the eighteenth-century book trades. With the wider digitization of records since Treadwell’s work in the 1970s and 1980s, as well as broader reevaluations of what counts as important, who knows what else of significance we might find.

Note: the late eighteenth-century chart was updated on 8/11/22 thanks to some helpful critique from Aaron Pratt.

WPHP Records Referenced

Anne Dodd I (firm)

Anne Dodd II (firm)

Edmund Curll (firm)

Rebecca Bonwicke (firm)

True Character of the Rev. Mr. Whitefield (title)

Manley, Delarivier (person)

John Barber (firm)

James Woodward (firm)

John Morphew (firm)

Churchill, Sarah Churchill (person)

Pope, Alexander (person)

James Bettenham (firm)

Lawton Gilliver (firm)

Haywood, Eliza (person)

A Short View of the Conduct of the King of Sweden (title)

A Caveat against the Tories (title)

Elizabeth Cooke (firm)

Elizabeth Nutt (firm)

Sarah Popping (firm)

Works Cited

Carnell, Rachel. A Political Biography of Delarivier Manley. Pickering & Chatto, 2008.

King, Kathryn R. A Political Biography of Eliza Haywood. Routledge, 2012.

Maruca, Lisa. The Work of Print: Authorship and the English Text Trades, 1660-1760. U of Washington P, 2007.

Nichols, John. Literary Anecdotes of the Eighteenth Century. Printed for the Author, by Nichols, Son, and Bentley, at Cicero’s Head, Red-Lion-Passage, Fleet-Street. 1812. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Literary_Anecdotes_of_the_Eighteenth_Cen/2EgJAAAAQAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0.

Raven, James. The Business of Books: Booksellers and the English Book Trade. Yale UP, 2007.

Raymond, Joad. Pamphlets and Pamphleteering in Early Modern Britain. Cambridge UP, 2003.

Rose, Mark. “Copyright, Authors and Censorship.” The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain, edited by Michael F. Suarez SJ and Michael L. Turner, Cambridge UP, 2009, pp. 118–31.

Ross, Trevor. “Copyright and the Invention of Tradition.” Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 26, no. 1, Autumn 1992, pp. 1–27.

Sutherland, James R. “The Dunciad of 1729.” The Modern Language Review, vol. 31, no. 3, July 1936, pp. 347–353.

Treadwell, Michael. “Dodd [née Barnes], Anne.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford UP, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/56591.

Treadwell, Michael. “London Trade Publishers 1675–1750.” The Library, vol. 6, no. 2, June 1982, pp. 99–134.

Vander Meulen, David L. “The Printing of Pope's ‘Dunciad’, 1728.” Studies in Bibliography, vol. 35, 1982, pp. 271–85.