This post is part of our Down the Rabbit Hole: Researching Women in the Book Trades Spotlight Series, which will run through August 2022. This series seeks to make transparent some of the processes, challenges, and editorial choices our team has to make while falling down the inevitable rabbit holes involved in finding, and creating data for, women in the book trades.

Authored by: Isabella (Belle) Eist

Edited by: Michelle Levy, Kandice Sharren, and Kate Moffatt

Submitted on: 02/09/2022

Citation: Eist, Isabella. “Hidden in the Imprints: Introducing Ann Vernor, Bookseller and Publisher, Active 1793–1807.” The Women’s Print History Project, 2 September 2022, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/117.

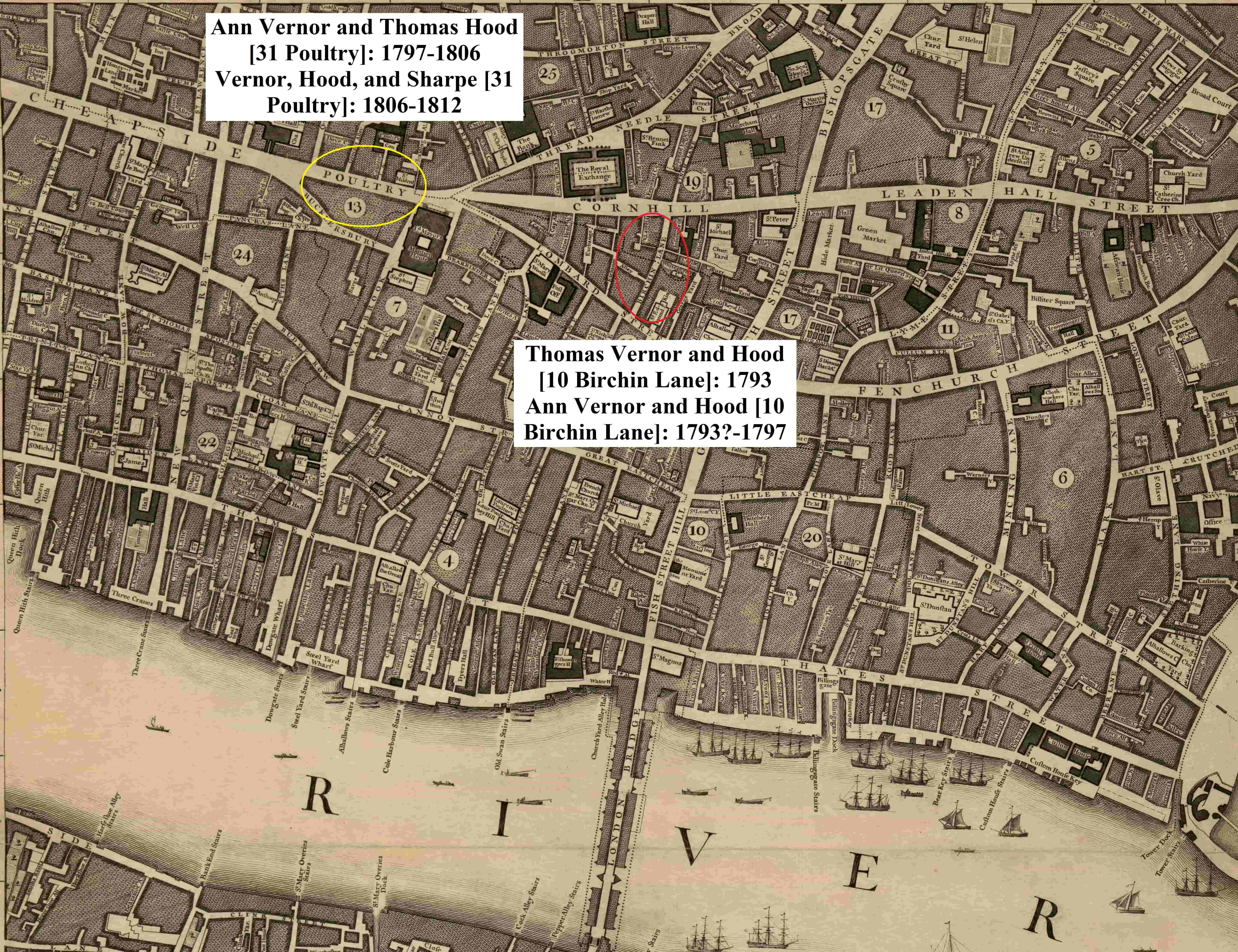

Figure 1. A table of the firms involving Thomas and Ann Vernor in the WPHP. Firms that were added or edited to reflect Ann Vernor’s contributions are highlighted in blue (my emphasis).

When Ann Vernor died on 9 November 1807, The Times described her as the “relict of Mr. Thomas Vernor,” her husband, who had been well known around London as a publisher, bookseller, and owner of a circulating library prior to his death in 1793 (Exeter). This brief obituary failed to recognize Ann Vernor’s own involvement in the London book trades. Based on my research, Ann Vernor had taken over the running of the publishing house after her husband’s death, in 1793, and was active at two locations and with two male partners between 1794 and 1807 (see figure 1). Nevertheless today, Ann Vernor remains unknown, hidden in the historical record behind her husband’s shadow and obscured by ongoing assumptions that understand women in imprints as exceptionable. The process of finding Ann Vernor, gathering evidence for her involvement in the firms associated with her surname, and finally composing this spotlight, demanded research in the familiar academic sources we use for the WPHP and also some new ones, such as popular genealogical websites. With no scholarly source acknowledging Ann Vernor’s participation in the firm, the first concrete steps to authenticating her work began with two disparate sources: one, an insurance record in Ann Vernor’s name, preserved in the London Metropolitan Archives catalogue of policy registrations with the Royal and Sun Alliance insurance group and two, Trevor Pickup’s research in WikiTree—essentially the Wikipedia of online genealogy tools—on prominent families associated with the Sandemanian Church, of which the Vernor family were members. A third critical piece of evidence, Thomas Vernor’s will, which specified his desire for Ann Vernor and Thomas Hood to carry on his “present business of a bookseller…in the same manner as late,” supplied further evidence for Ann Vernor’s work in the firm (“Will of Thomas Vernor, Bookseller of Birchin Lane, City of London”). Ultimately, less traditional academic sources, like WikiTree, that I would have previously sought out as a last resort while researching, provided the most extensive information available on Ann Vernor for evidence of her unacknowledged and hitherto unknown career.

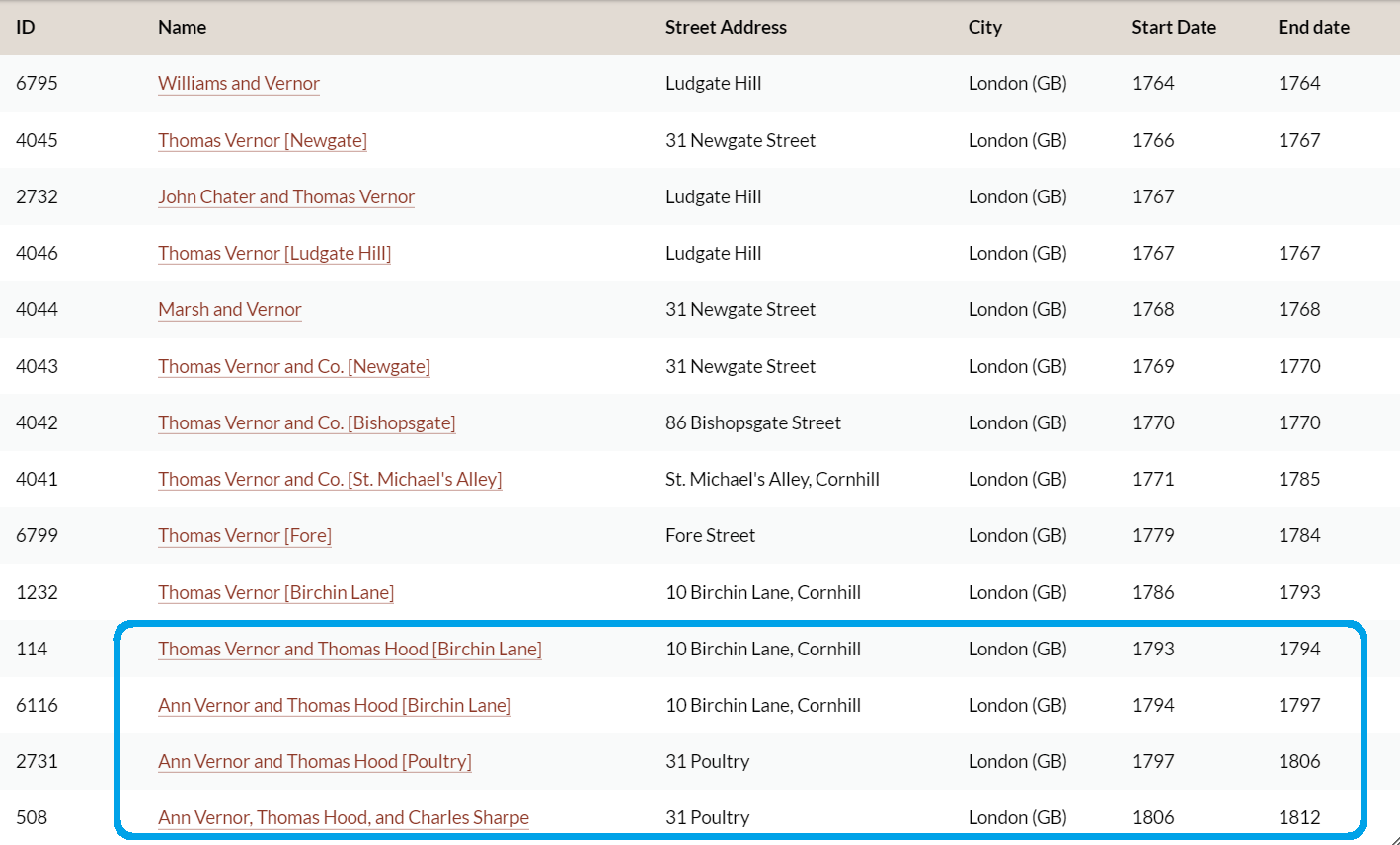

Hidden Women and Dead Husbands

The road to discovering Ann Vernor’s involvement in the book trades began with research I conducted on Mary Susanna Pilkington, a writer of didactic children’s literature who worked for over a decade as a writer and editor for the Lady’s Monthly Museum, a magazine published by Vernor, Hood, and (later) Sharpe and written “By a society of ladies.” My focus on Pilkington, which brought about my first encounter with Vernor, Hood, and Sharpe’s firm, began in WPHP Project Director Dr. Michelle Levy’s Fall 2021 course, titled “Eminent Women of the Long Eighteenth Century,” on the writers and artists featured in William Upcott’s album of Eminent Women (see Original Letters of Eminent Women for more information on Dr. Levy’s course and the Upcott album). Transcribing Pilkington’s October 1810 letter to her publisher supplied a name, “Mr. Sharpe,” a firm category, “bookseller,” and a location, “Poultry,” providing ample data to take to the WPHP’s advanced firm search feature for further information. Our firm records identified Pilkington’s addressee as Charles Sharpe, the tertiary member in Vernor, Hood, and Sharpe, a publishing and bookselling firm based in London. Without any forenames, we assumed, as had anyone who had considered the firm previously, that all three partners were men. Prior to locating evidence for Ann Vernor’s partnership in the firm after 1793, references to the firm as “Messrs” in imprints (such as in the 1806 title, The Anatomy of Melancholy; see figure 2) and in letters to the firm reinforced a conventional narrative that firm partners shifted largely through patrilineal succession if the deceased had a son of age to take over his place in the firm. In other words, we assumed that the Mr. Vernor mentioned in titles like this would have been Thomas or Ann Vernor’s eldest son. During her visit to the British Library this summer, Dr. Michelle Levy examined Upcott's four collections of letters by "Distinguished Women" and shared her findings on how authors in communication with the firm addressed the publishers: typically using "Messrs" or "Misters." Acknowledging that the firm members were addressed in this manner by both interested and returning writers suggests that Ann Vernor's work in the firm may not have been visible or known to the public, just as it was not visible in their imprints (Original Letters collected by William Upcott of the London Institution. Distinguished Women).

Figure 2. The imprint describes Vernor, Hood, and Sharpe as “Messrs” in The Anatomy of Melancholy, 1806. Google Books.

In September 2021, when I began researching the Vernor family, the data we had in our firm records indicated that Thomas Vernor and Thomas Hood’s business partnership began in 1793, with the much younger Sharpe joining in 1806. At the time of the October 1810 letter I transcribed from Pilkington to Sharpe, Pilkington had been working with Vernor and Hood for twelve years on The Lady’s Monthly Museum and for eleven years as one of their published authors. I questioned why Pilkington would be communicating with Sharpe when she had an enduring business relationship with the more senior members of the firm; this line of questioning drew me to the British Book Trade Index and the Exeter Working Papers in Book History, two frequently consulted sources for the WPHP’s firm records. My research into Sharpe’s partners became relevant to the WPHP’s mission to spotlight unsung women in the book trades when Thomas Vernor’s record in the BBTI recorded his death as 1793, almost two decades before Vernor, Hood, and Sharpe filed for bankruptcy in 1812 and Vernor’s name finally ceased to appear in imprints. The only other Vernor listed in the BBTI was Thomas Vernor's son, George Glas Vernor, who worked as an Apprentice of the Stationers' Company but has no further information available about his work in the book trades. Following project manager Kate Moffatt’s lead in her 2020 spotlight, “A Search for Firm Evidence: Uncovering Ann Sancho, Bookseller,” I looked next to Ian Maxted’s Exeter Working Papers in Book History for hidden evidence of the unknown Vernor successor. Moffatt’s observation, “Finding women involved in the book trades requires us to read systematically through every entry of our various resources in an effort to find traces of women's involvement,” holds true two years later: I found the first and only reference to a “Mrs. Vernor” at the end of several lengthy descriptions of Thomas Vernor in Exeter. Though this reference merely included her short obituary as it appeared in The Times (quoted above, calling her the “relict of Mr. Thomas Vernor”), the absence of any evidence supporting her son’s involvement in the firm implied “Mrs. Vernor” was a worthy lead to pursue, though I could not yet discount the possibility that George inherited his father’s position.

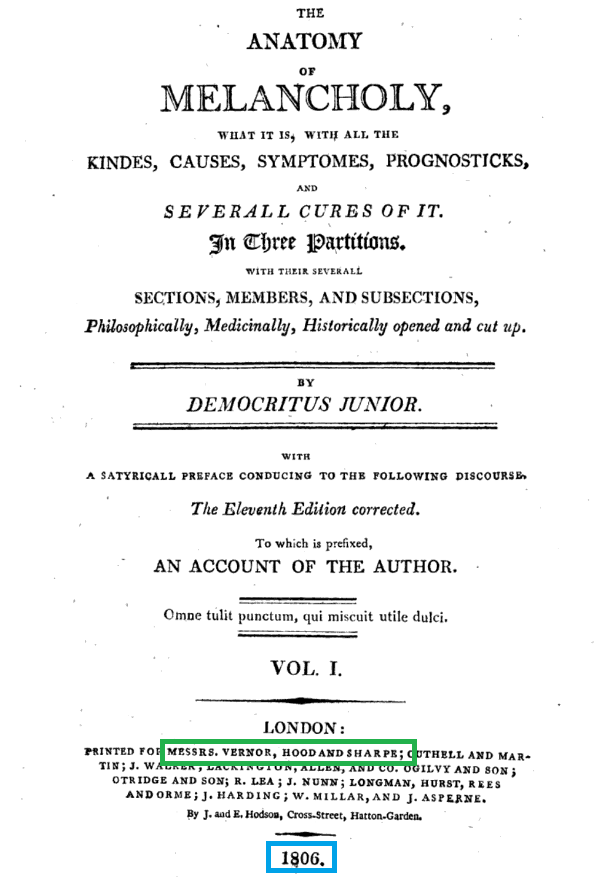

A Google search for “Thomas Vernor widow” yielded Mrs. Vernor’s first name, Ann, in a personal blog post by Edward Pope on his website Ed Pope History. Pope writes: “Thomas Vernor died in 1793 and was succeeded by his widow Ann” (Pope “Vernor”). The blog provided no sources for this claim, but Ann Vernor’s full name, combined in a Google search with keywords like “bookseller” and “publisher,” eventually led me to an insurance document held in the “Royal and Sun Alliance Insurance Group” collection at the London Metropolitan Archives that corroborates Ann Vernor’s partnership with Thomas Hood. The insurance record, entitled “Insured: Ann Vernor and Thomas Hood, 31 Poultry, Booksellers,” was purchased from the Sun Fire Office on 5 July 1797, the same year the firm moved its operations from 10 Birchin Lane to 31 Poultry (see these firm addresses mapped in figure 3). Notably, Moffatt’s spotlight highlighted that the most definitive documentation for Ann Sancho’s work in the book trades was the insurance policy held by the Sun Fire Office, and it is fascinating that a key piece of evidence for Ann Vernor’s role in the business is an insurance agreement with the same firm. Though she does not appear in any scholarly research that mentions Thomas Vernor (or Thomas Hood, John Chater, or any other of Vernor’s earlier business partners) and did not include a first initial in any of the imprints, as Thomas Vernor customarily did (for example, of the 196 titles in the Eighteenth Century Collections Online associated with Thomas Vernor before his death, 160 of these titles include his first initial in the imprint), this insurance policy verifies Ann Vernor’s position as the “Vernor” in “Vernor and Hood” at the Poultry address in 1797. Still, what remained to be seen after this discovery was the extent of her work in the firm during the first four years of their tenure at the Birchin Lane address and in the years following 1797.

Figure 3. Highlighting Vernor and Hood’s addresses at 10 Birchin Lane and 31 Poultry (my emphasis) in John Rocque’s A plan of the cities of London and Westminster, and borough of Southwark, with the contiguous buildings, 1746, sheet 2e. Wikimedia Commons.

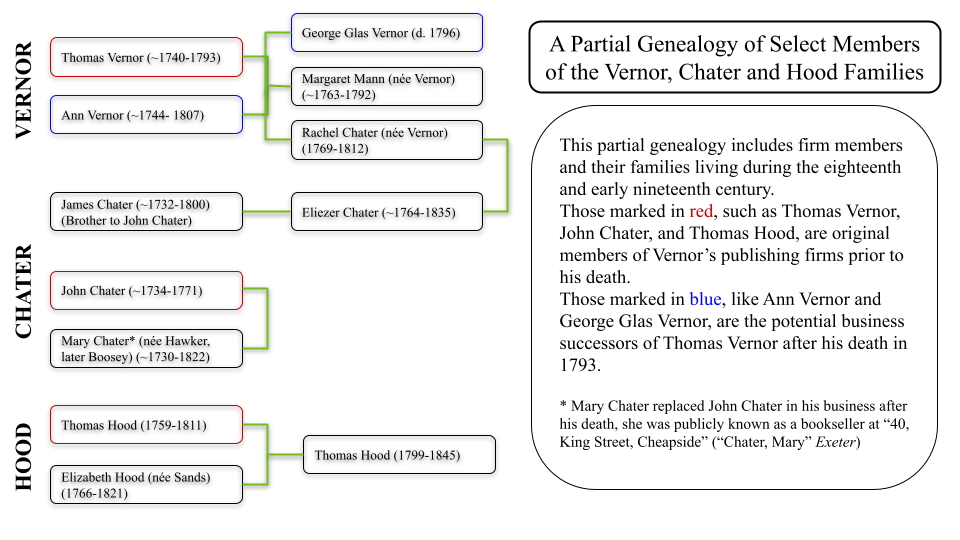

WikiTree genealogist Trevor Pickup’s research centers around Nonconformists and Sandemanian Church members in London during the late eighteenth century; he has extensively investigated the genealogy of the Vernor family, who, alongside Vernor’s early business partner Chater, were well-known members and elders in the London Sandemanian Church [“Thomas Vernor (abt. 1740 - 1793)”]. Since June 2020, Pickup has added records for Thomas Vernor and Ann Vernor, and for their children, George Glas Vernor, Rachel Chater (née Vernor), and Margaret Mann (née Vernor). Though not a conventional scholarly source or a well-funded genealogy site, WikiTree is a valuable historical resource because it is accessible and demonstrates what history can look like when it is created by and for everyone. As a database that collects and compiles information from other databases, including sources posing steep financial barriers, the WPHP emulates this commitment to accessibility as a free resource working to reduce barriers to access in book history, literary studies, and women’s history. After a protracted and often convoluted research process as I unsuccessfully tried to validate Ann Vernor’s partnership in the firm using scholarly sources and databases, it was Pickup’s list of sources in WikiTree that directed me first to George Vernor’s burial record in the England and Wales Non-Conformist Record Indexes, logging his death in April 1796, and then to Thomas Vernor’s will, held in The National Archives and viewable online. George Vernor’s burial record proves he could not have been operating in the firm after 1796, but it is Thomas Vernor’s will that provides the principal evidence that Ann Vernor’s partnership with Thomas Hood directly followed Thomas Vernor’s death, as per his stated wishes in his will.

The Timeline and the Players: Authenticating Ann Vernor’s Involvement

Figure 4. “A partial genealogy of select members of the Vernor, Chater, and Hood families.” Belle Eist, 2022.

Figure 4. “A partial genealogy of select members of the Vernor, Chater, and Hood families.” Belle Eist, 2022.

Imprints and the BBTI suggest Thomas Hood (1759-1811) joined Vernor’s firm in 1793, when Vernor was still operating out of 10 Birchin Lane. Though Thomas Vernor and Thomas Hood’s official partnership lasted less than a year, Vernor’s will recognizes Hood as his partner and desires the continuation of the firm, stating “it is my will and desire that my present Business of a Bookseller now carried on in Birchin Lane be carried on by and between my said Executrix and Executors (as Trustees) and my partner Thomas Hood in the same manner as late” (“Will of Thomas Vernor”). His desire for the inclusion of his executrix, Ann Vernor, in the continuation of his firm suggests that her partnership with Thomas Hood began before Thomas Vernor’s death; this is the only way to interpret the expressed wish of Thomas Vernor that Hood and Ann Vernor carry on the business “in the same manner as late.” Indeed, he is unlikely to have entrusted her with the business had she not had previous experience running the firm.

Further evidence for Ann’s importance to the firm is found in another provision of his will. Both Ann Vernor and Thomas’s son-in-law, Eliezer Chater (nephew of Vernor’s late business partner; see figure 4 for an illustration of firm and family connections between the Hood, Vernor, and Chater families), were named executors, and Ann Vernor and George Glas Vernor (their eldest son) were named as beneficiaries. However, Thomas Vernor’s will stipulates his son was to receive “the sum of Eighty pounds per annum…as [Ann Vernor] may see [fit]” only “if the conduct of my said son shall prove commendable and satisfactory to my Executrix and Executors (but not otherwise) and he shall prove diligent which is to be judged by my Executrix and Executors” (“Will of Thomas Vernor”). Other sections of the will implied Thomas Vernor had concerns about George’s behaviour, character, and maturity, further indicating that George would not have been trusted with the management and co-ownership of the firm.

Vernor was buried in October of 1793, but he continued to appear in imprints through 1794, often denoted by his initials, “T. Vernor” (ECCO). In the English Short Title Catalogue and Eighteenth Century Collections Online, two titles published in 1793 highlight Thomas Vernor and Thomas Hood’s brief partnership in the imprints as “T. Vernor and Hood, Birchin-Lane” and only a single title from 1794 lists both of their first initials as “T. Vernor and J. Hood.” The otherwise infrequent use of initials after 1794 makes it difficult to ascertain what may have been Thomas Vernor’s work and what was Ann Vernor’s in the 1794 transition period within the firm after Thomas Vernor’s death in late 1793. Because there are a few titles published in 1794 with Thomas’s initial included in the imprint, it would be reasonable to assume that he had worked on a number of titles before his death that were published the next year, but this does not discount Ann Vernor’s involvement in the firm throughout 1794.

For over thirteen years, Ann Vernor worked alongside Hood and then Sharpe, who joined the firm (now Vernor, Hood, and Sharpe) in 1806 (WPHP). During this period, the firm published and sold over six hundred titles (the English Short Title Catalogue lists 653 titles where “Vernor” appears in the imprint between 1794 and 1807). These 653 titles are slowly being imported into the WPHP from the ESTC. Thomas Vernor’s practice of including his first initial died with him, and Ann Vernor signed only her married name in imprints; though the inclusion of an initial would not have revealed Ann Vernor’s gender, it would have officially acknowledged that Thomas Vernor had been replaced, which may not have been a fact the firm wanted to make explicit. Amid two other firm members recognized only by their surname in imprints, the absence of Ann Vernor’s initial should not discredit her presence in the business. Although Ann Vernor was not a visible woman in the imprints, conventional assumptions that book trade business partners were almost inevitably men—which I found myself falling into and had to work against in collecting evidence to disprove George Vernor’s involvement as the oldest son—may impede recognition for women booksellers and publishers even more than the patriarchal landscape of eighteenth and nineteenth-century England, which may have led some women to omit gendered indicators for female firm members from their imprints.

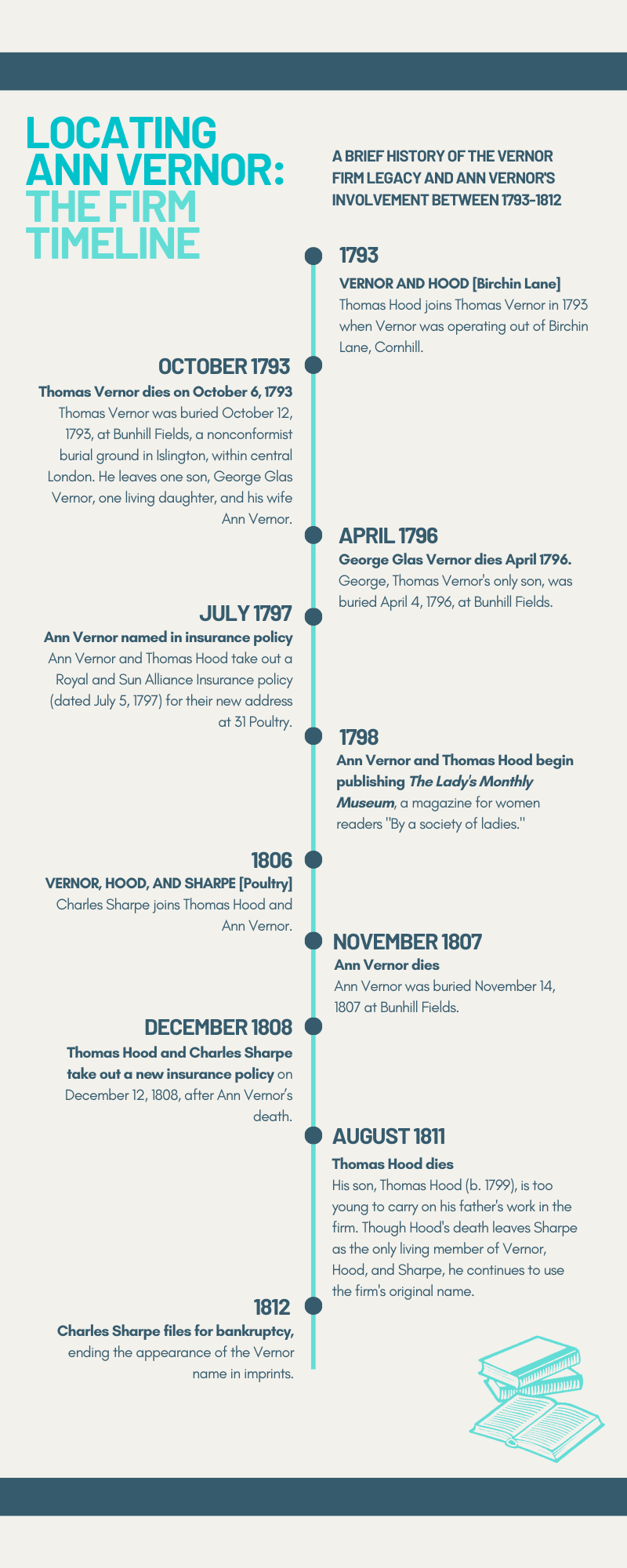

Ann Vernor died on 9 November 1807, followed by Thomas Hood in 1811; Hood’s son (also named Thomas Hood) was too young to replace his father in the firm at twelve years old, leaving Charles Sharpe as the only living member of Vernor, Hood, and Sharpe. The firm dissolved in 1812 when Sharpe went bankrupt, finally effacing the Vernor name from the imprints in The Museum and on titles the firm sold and published (see figure 5 for a review of the firm’s timeline).

Figure 5. “Locating Ann Vernor: The Firm Timeline.” Belle Eist, 2022.

Figure 5. “Locating Ann Vernor: The Firm Timeline.” Belle Eist, 2022.

WPHP Records Referenced

Vernor, Ann (person, bookseller and publisher)

Pilkington, Mary (person, author)

Ann Vernor, Thomas Hood, and Charles Sharpe (firm, bookseller and publisher)

Thomas Vernor and Thomas Hood [Birchin Lane] (firm, bookseller and publisher)

Sancho, Ann (person, bookseller)

Ann Vernor and Thomas Hood [Birchin Lane] (firm, bookseller and publisher)

Ann Vernor and Thomas Hood [Poultry] (firm, bookseller and publisher)

WPHP Spotlights Referenced

“A Search for Firm Evidence: Uncovering Ann Sancho, Bookseller” (spotlight by Kate Moffatt)

Works Cited

Eighteenth Century Collections Online. www.gale.com/primary-sources/eighteenth-century-collections-online. Accessed 23 June 2022.

English Short Title Catalogue. estc.bl.uk. Accessed 26 June 2020.

“Insured: Ann Vernor and Thomas Hood, 31 Poultry, Booksellers.” London Metropolitan Archives Collection Catalogue, 5 July 1797, search.lma.gov.uk/scripts/mwimain.dll/144/LMA_OPAC/web_detailSESSIONSEARCH&exp=refd%20CLC/B/192/F/001/MS11936/409/668341.

Maxted, Ian. “Vernor, Thomas.” Exeter Working Papers in Book History, bookhistory.blogspot.com/ search?q=vernor. Accessed 25 June 2022.

Moffatt, Kate. "The Search for Firm Evidence: Uncovering Ann Sancho, Bookseller." The Women's Print History Project, 25 June 2020, www.womensprinthistoryproject.com/ blog/post/20.

Pickup, Trevor. “Thomas Vernor (abt. 1740 - 1793).” WikiTree, 12 June 2020, www.wikitree.com/wiki/Vernor-52.

Pope, Edward. “Vernor.” Ed Pope History, edpopehistory.co.uk/entries/vernor/1809-09-26-000000. Accessed 24 June 2022.

Upcott, William. Original Letters collected by William Upcott of the London Institution. Distinguished Women. British Library, Add. MS 78686-78689, searcharchives.bl.uk/IAMS_VU2:LSCOP_BL:IAMS036-002037641.

“Will of Thomas Vernor, Bookseller of Birchin Lane, City of London.” The National Archives, 29 October 1793, discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/D353734.