This post is part of our By Our Books: Bibliography in the WPHP Spotlight Series, which will run through July 2023. This series attends to the bibliographical fields of the WPHP title records, tracing the history of our thinking about our descriptive practices and how they are informed by the sources available to us and by our feminist ambition to recognize and reconstruct women’s labour in print, broadly conceived.

Authored by: Sara Penn

Edited by: Michelle Levy

Submitted on: 07/05/2023

Citation: Penn, Sara. “What's in a Title?” The Women’s Print History Project, 5 July 2023, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/121.

Figure 1.

Titles allow us to see a larger literary field.

– Franco Moretti

Most of the information that we gather from books are collected from their title pages. The WPHP relational data model centres around them for this reason; we can often glean from the title page not only the title and subtitle of the book, but also its author(s), edition, location of publication, genre, price, and possibly even advertisements, printer’s marks, and much, much more. As Whittney Trettien reminds us, “The title page is the site of a book’s self-presentation to its potential audience, where it informs readers about a text by in-forming—moulding into structured information—the facts of its production” (41). This blog post will discuss the sometimes forthright, sometimes playful, or sometimes even misleading aspect of the title page—the Title itself—to more fully understand its use in the WPHP.

As defined in our Documentation, the WPHP understands the capital-T Title as the “Full title as it appears on the title page, including subtitle, signed author, and edition statement, where applicable.” In other words, the Title, much like the title page on which it rests, can inform our understanding about the textual and material contents of a book, alongside clues to its possible readers and status.

Titles in the WPHP refer to books produced by women Contributors during the years 1700 to 1836 from England, Scotland, Ireland, America, and France. Titles include all Formats and most Genres. We amalgamate Title information from over 100 existing Sources, such as archives, databases, textbases, and physical libraries. At least one out of two sources that we consult to verify the existence of a Title must be digitized. If we are lucky, we can verify books by hand-checking them in-person and manually entering them in the database. The team’s visit to the Chawton House Library, where much of the data collection began, is discussed in Season 1, Episode 1 of The WPHP Monthly Mercury.

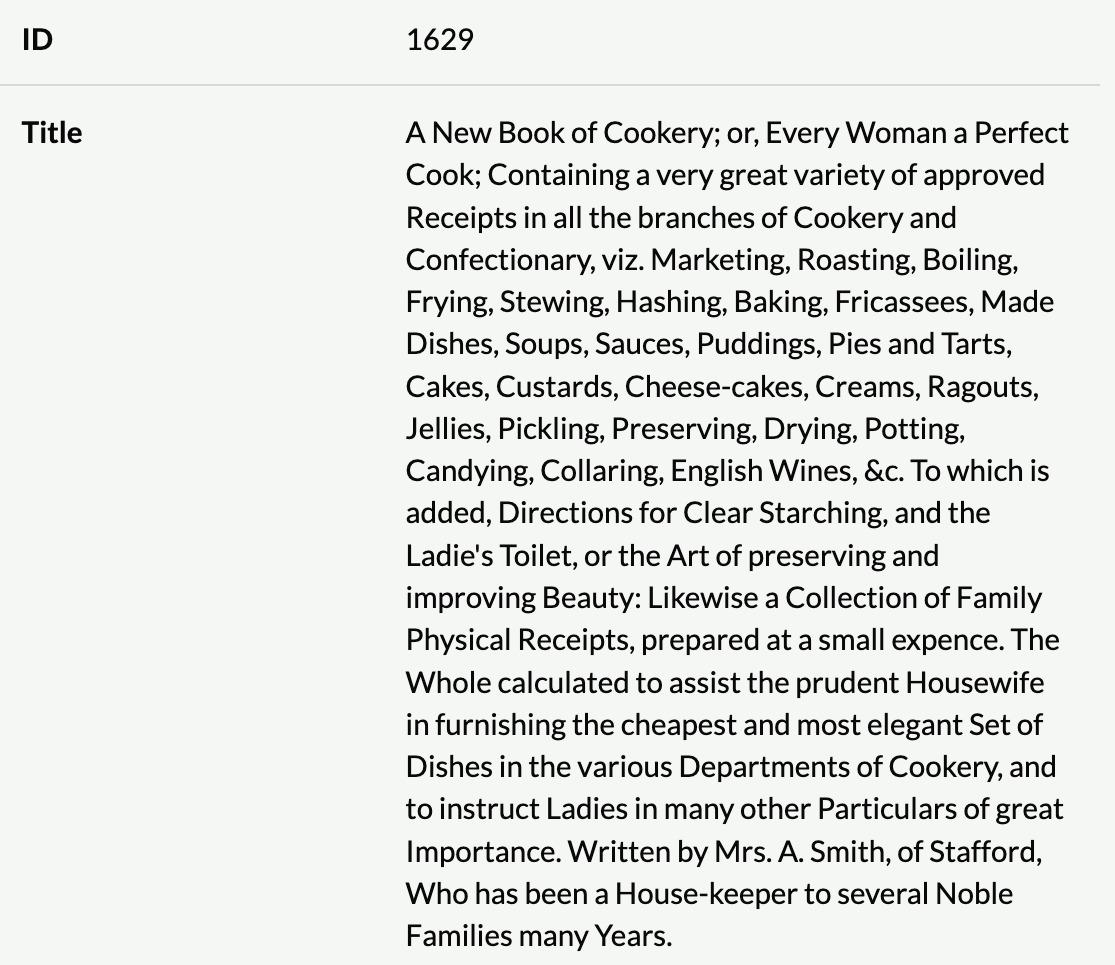

In terms of the WPHP, the Title alone can link us to an array of other metadata fields. Let us use Ann Radcliffe’s 1794 Mysteries of Udolpho as an example.

Figure 2.

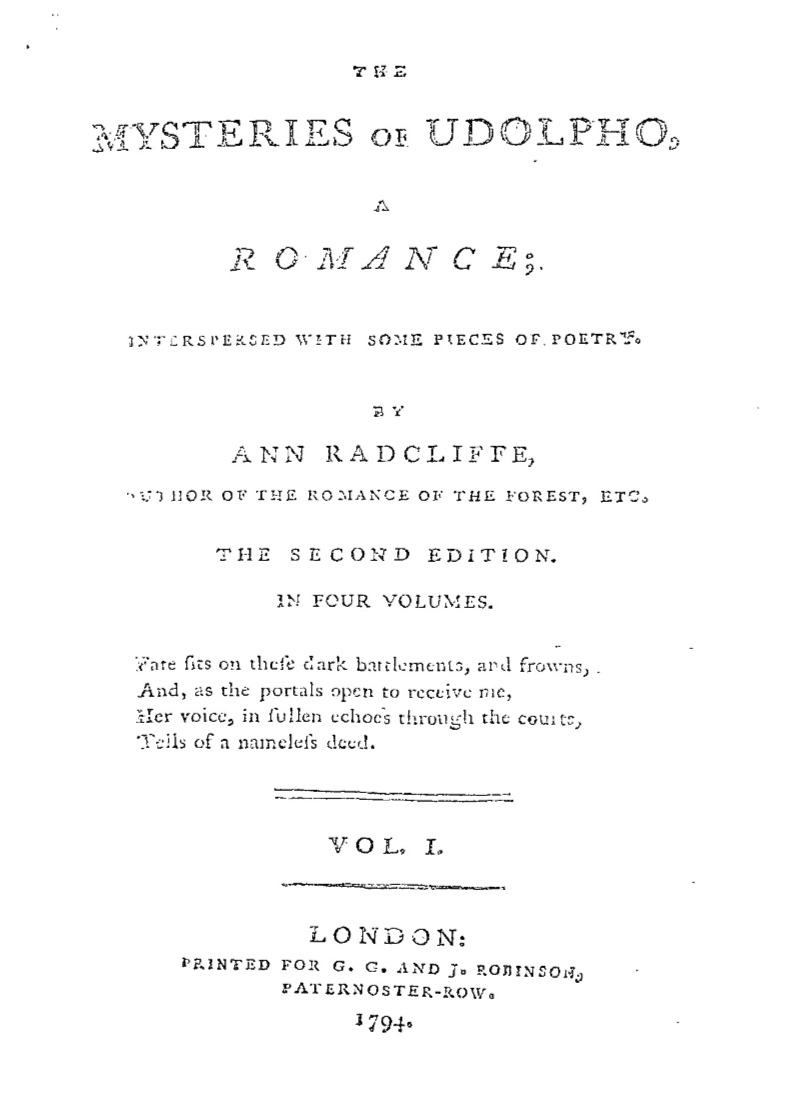

This particular Title is derived from Eighteenth-Century Collections Online, otherwise known as ECCO. We then transform this information into a Title record, seen below:

Figure 3.

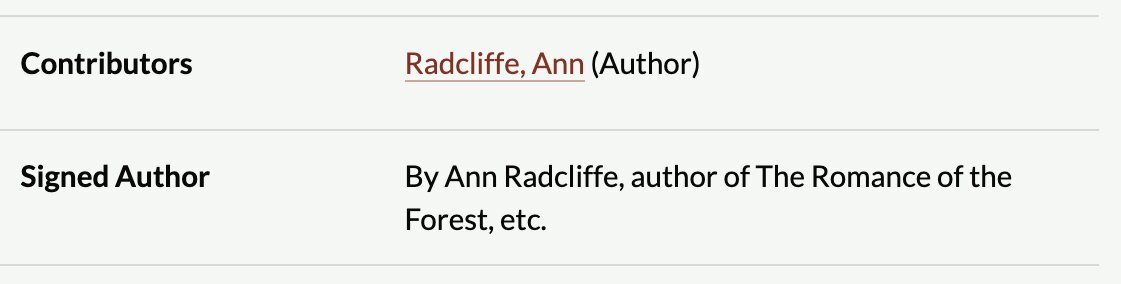

The contents of the full Title can be separated into other Title fields. For example, “Ann Racliffe, Author of the Romance of the Forest” allows us to add Radcliffe as a Contributor (Author) and include her signature in the Signed Author field:

Figure 4.

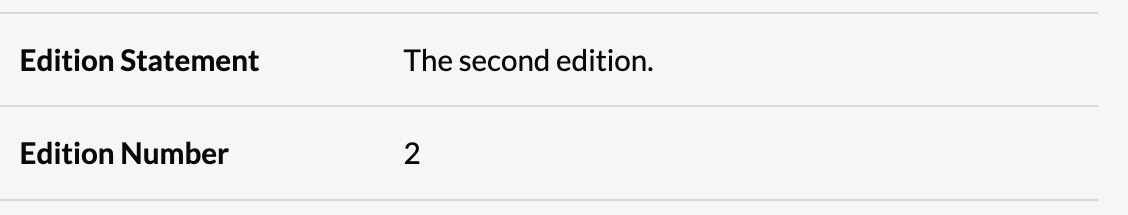

“The second edition” tells us we can fill out the Edition Statement and Edition Number.

Figure 5.

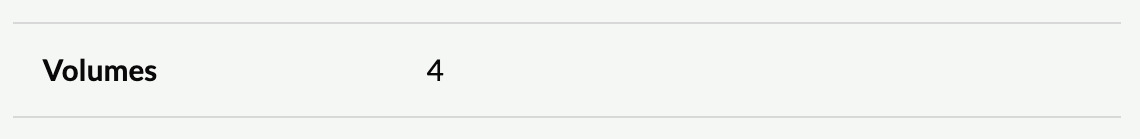

“In four volumes” allows us to complete the Volumes field:

Figure 6.

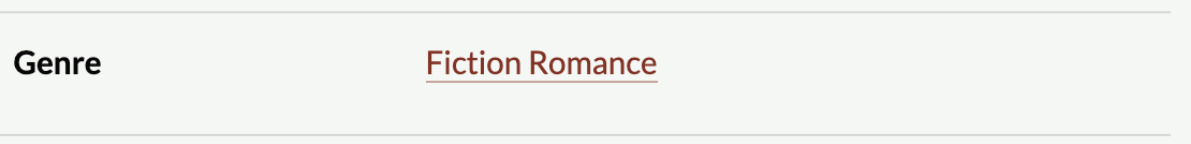

And finally, “A romance” allows us to fill out the Genre as a Fiction Romance:

Figure 7.

Figure 7.

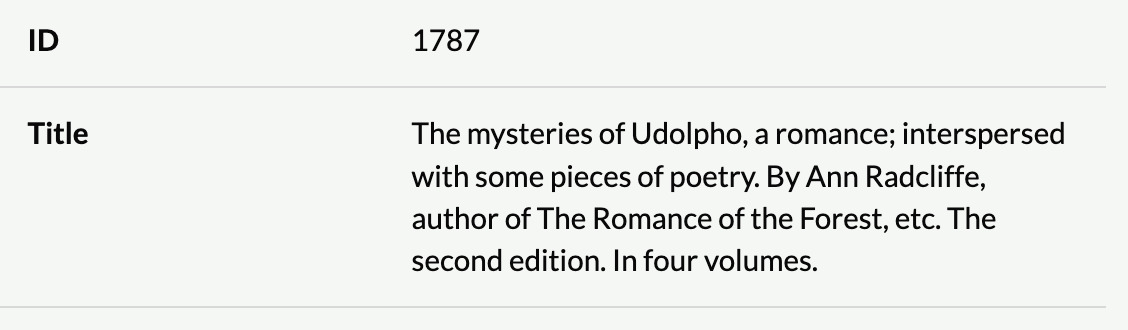

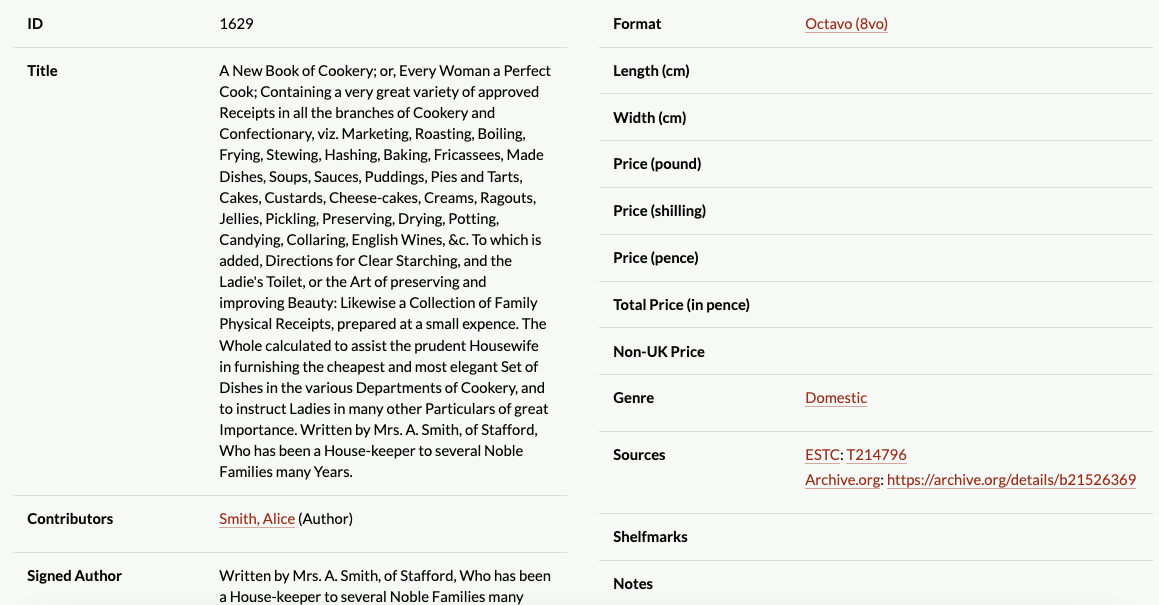

It is important to note that we always include the full Title, even when it is very long. Our goal is to capture these complete titles, because, as Michelle Levy argues, they are often abbreviated in other sources: “the limitations of print (and even some early computer-based resources, like the English Short Title Catalogue) have impacted not only the usability but the accuracy and completeness of records” (5). We deliberately include all 144 words (!) of Alice Smith’s New Book of Cookery, for example, in order to achieve more concise metadata (as seen below).

Figure 8.

While Titles in the WPHP may not always capture all of these elements, they serve as what Franco Moretti deems “the most public part of a book” (145), directing us to other subfields in our database. Indeed, considering that some books remain undigitized, we rely on full titles to fill out other fields, as we lack the resources to manually examine every book to determine, for instance, its genre. As Moretti has argued in his analysis of over 7,000 British titles, an examination of titles themselves can reveal themes and tropes of the era, as well as the evolving nature of literary production and the development of the novel. Our metadata therefore facilitates this type of study.

There are over 15,000 Titles to explore in our database, many of which can be moralizing (The Story of Sinful Sally); excitable (The Three Monks!!!); bizarre (The Strange and Unaccountable Life of the Penurious Daniel Dancer, Esq. A Miserable Miser, Who Died in a Sack); or even, as Kate Ozment recently discovered, condescending (An essay to prove women have no souls). While it may be easy to overlook Titles as individual datasets, conducting a comprehensive examination of them enables us to endeavour to address Devoney Looser's 2015 question, "Just how much women's writing has been published in English?" (165), and observe a more illustrative landscape of women's contributions to print.

To explore Titles, click here.

To search Titles, click here.

To explore our Project Methodology on Titles, click here.

To explore our Spotlights on Titles, click here.

WPHP Records Referenced

Documentation (methodology)

Contributors (field)

Formats (field)

Genres (field)

Sources (field)

The WPHP Monthly Mercury (podcast)

The WPHP Monthly Mercury, Season 1, Episode 1 (podcast episode)

The Mysteries of Udolpho (title)

ECCO (source)

Signed Author (field)

Edition Statement (field)

Edition Number (field)

Volumes (field)

Fiction Romance (genre)

A New Book of Cookery (title)

The Story of Sinful Sally (title)

The Three Monks!!! (title)

Kate Ozment (team member)

An essay to prove women have no souls (title)

Works Cited

Levy, Michelle. "Women’s Books, 1750–1830." Unpublished manuscript.

Looser, Devoney. “British Women Writers, Big Data, and Big Biography, 1780–1830.” Women's Writing 22, no. 2 (2015): 165–171.

Moretti, Franco. “Style, Inc. Reflections on Seven Thousand Titles (British Novels, 1740–1850).” Critical Inquiry, vol. 36, no. 1, Autumn 2009, pp.134–58.

Trettien, Whitney. “Title Pages.” In Book Parts, edited by Dennis Duncan, and Adam Smyth, Oxford UP, 2019, pp. 39–50.