This post is part of our By Our Books: Bibliography in the WPHP Spotlight Series, which will run through July 2023. This series attends to the bibliographical fields of the WPHP title records, tracing the history of our thinking about our descriptive practices and how they are informed by the sources available to us and by our feminist ambition to recognize and reconstruct women’s labour in print, broadly conceived.

Authored by: Julianna Wagar

Edited by: Michelle Levy, Kate Moffatt, and Kandice Sharren

Submitted on: 07/28/2023

Citation: Wagar, Julianna. "What's in a Name?: Pseudonymous Texts in the WPHP." The Women's Print History Project, 28 July 2023, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/124.

The pseudonym field in our WPHP title records is used to capture the “false or fictitious name; an alias” (OED) that an author has published under for a particular title. It is used in addition to the signed author field, which Kate Ozment has discussed in further detail in her Spotlight, “The Language of Authorship.” Household pseudonyms such as Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell (used by the Brontë sisters) are now recognizable as pseudonyms—their novels were published under their real names after their original publications were successful (Whitehead 59). This is common with pseudonyms: authors who originally published under a pseudonym begin publishing under their own name as their work grows in popularity.

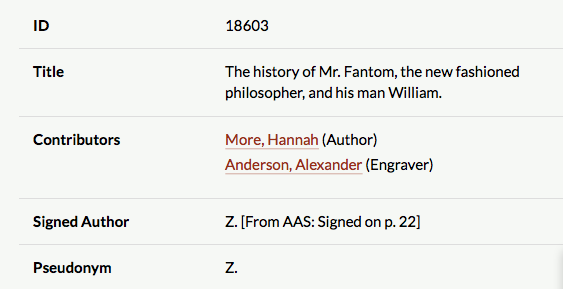

Hannah More is one such example, as she originally published under a pseudonym but eventually published under her own name. Some of her earliest work is published “by a Lady” or simply “Z.” While “by a Lady” would not be classified as a pseudonym, as it is not a fictitious name, “Z.” hints at a name other than More’s own. Based on these signatures alone, it would be difficult to attach a person to any of these titles; however, More was one of the most popular writers in the late eighteenth century and her anonymously and pseudonymously published works have long been linked to her. In particular, “Z.” was the pseudonym More used for her contributions to the Cheap Repository Tracts (Hole xlvii), although it typically appears at the end of the preface, rather than on title pages. Thus, the WPHP captures that More used a pseudonym early on in her career by adding “Z.” to the Signed Author field and the Pseudonym field and attaching More as the author.

There is an assumption that women took on pseudonymous names in order to hide their gender (Ezell 63), but that is not always the case. There are many reasons that one may decide to use a pseudonym; as Mark Vareschi writes, “when presented with the name of the author, we typically come to characterise and know the text through the figure of the author: we have formed a named agent ostensibly responsible for the text; we have a name under which to catalogue the text” (1). As the WPHP data shows, pseudonyms weren’t only or even primarily used to disguise an author’s gender—they could contribute to an author’s textual performance or to shield an author from public recognition.

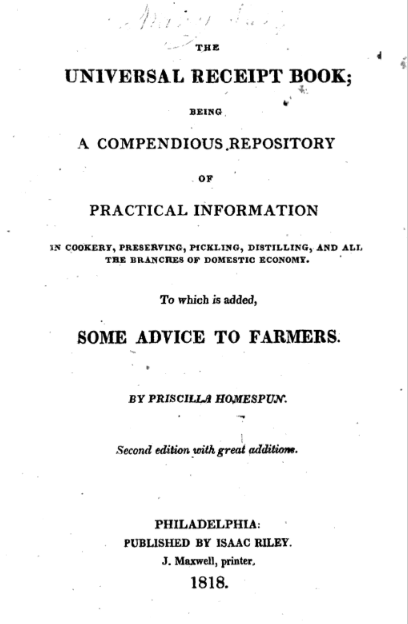

Pseudonyms could be used to communicate the genre of a book. Priscilla Homespun is the author of The universal receipt book; being a compendious repository of practical information in cookery, preserving, pickling, distilling, and all the branches of domestic economy. To which is added, some advice to farmers. Her last name, “Homespun,” is directly related to the topic of her work, domestic work, which both communicates the genre she publishes in and textually performs knowledge in the area to her audience. An author name that aligns with the topic of the text is also an obvious cue that it is a pseudonym, even though we have not yet been able to identify the author behind “Priscilla Homespun.”

Mrs. Meanwell is another example of textual performance by a pseudonym—her works are lessons for children, such as The Entertaining History of Master Billy, and Miss Polly Kindly: written for the entertainment and instruction of all the little good boys, and girls, who are able and willing to read it. The fictitious name literally states that the author “means well,” which aligns with the genre of her educational and instructional texts.

Uncovering a pseudonymous author can be done in a myriad of ways. The most obvious way is only applicable to those who have published widely. For example, Emma de Lisle is the signed author of Eva of Cambria; or, the Fugitive Daughter. Her later works are published “by the author of Eva of Cambria,” and also by Amelia Beauclerc, which is her real name. Because these titles are associated through the signed author field, we learn that Emma de Lisle was a pseudonym and attribute all of these works to Beauclerc in the WPHP. When authors use a real name as a pseudonym, it can be much harder for us to determine their true identity.

In many instances, this research is time intensive; we rely on research available through the resources we use to verify titles—Eighteenth Century Collections Online, English Short Title Catalogue, American Antiquarian Society, etc.—that contains detailed information on the publication of a title. For example, A Letter to the Women of England on the Injustice of Mental Subordination claims to be authored by Anne Francis Randall on the title page, and in one or more of our resources. But in this case, the British Library attributes this pseudonym to the author’s real name: Mary Robinson. We can take that information and apply it to our data, noting that this research was done by an external source. In the case of Mary Robinson, Anne Frances Randall was one of the many names she published under; Daniel Robinson notes that she “employed various pseudonyms for periodical publications, but she rarely used them to disguise herself. Instead, when attached to poems in newspapers, they were ways of showcasing her poetic virtuosity” (142). She had different personas that allowed her to link particular pseudonyms to particular genres or poetic voices. By the time that her Letter was published, Robinson was already famous and may have wanted to separate the essay’s argument from her notorious celebrity. Regardless of her intention, the disguise was short-lived: the second edition was published under her real name.

If you are interested in pseudonyms in the WPHP, here is a list of some to explore. Try searching the following names in quotations in the Pseudonym field in the Advanced Title Search.

- Mrs. Bridget Bluemantle (Elizabeth Thomas)

- Prudentia Homespun (Jane West)

- Carolina Petty Pasty (Elizabeth Cobbold)

- Peregrine Reedpen (C.F. Adderley)

- Mira (Eliza Haywood)

- Explorabilis (Eliza Haywood)

- Mrs. Lovechild (Ellenor Fenn)

- Hannah Heartwhole (Hannah More)

- Will Chip (Hannah More)

- Joan Plotwell (True identity unknown)

- Mother Shipton (Ursula Southeil)

- Mrs. Teachwell (Ellenor Fenn)

- Theresa Tidy (Elizabeth Graham)

- Mother Bunch (Marie-Catherine d'Aulnoy)

- Mrs. Sharp-Set O'Blunder (Elizabeth de Franchetti)

- Madame Panache (Frances Moore)

- Miss Aimwell (True identity unknown)

- Lucretia Lovejoy (True identity unknown)

- Mrs. Artlove (True identity unknown)

WPHP Records Referenced

"The Language of Authorship" (spotlight by Kate Ozment)

Brontë, Curer/Charlotte (person, author)

Brontë, Ellis/Emily (person, author)

Brontë, Acton/Anne (person, author)

More, Hannah (person, author)

Cheap Repository Tracts (title)

Homespun, Priscilla (person, author)

Meanwell, Mrs. (person, author)

Eva of Cambria; or, the Fugitive Daughter (title)

Beauclerc, Amelia (person, author)

A Letter to the Women of England on the Injustice of Mental Subordination (title)

Robinson, Mary (person, author)

Thoughts on the condition of women, and on the injustice of mental subordination (title)

Works Cited

Ezell, Margaret J. M. “‘By a Lady’: The Mask of the Feminine in Restoration, Early Eighteenth-Century Print Culture.” The Face of Anonymity: Anonymous and Pseudonymous Publication from the Sixteenth to the Twentieth Century, Palgrave Macmillan, 2003, pp. 63–79.

Hole, Robert. “Introduction.” Selected Writings of Hannah More, ed. Robert Hole, Pickering, 1996, pp. vii-xlviii.

“Pseudonym.” Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford UP, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/527389968.

Robinson, Daniel. “Mary Robinson and the Problem with Tabitha Bramble.” The Wordsworth Circle, vol. 41, no. 3, 2010, pp. 142–46.

Whitehead, Stephen. “The Bell Pseudonyms: A Brontë Connection?” Brontë Studies, vol. 40, no. 1, 2015, pp. 59–64.

Vareschi, Mark. “Introduction: Everywhere and Nowhere.” Everywhere and Nowhere: Anonymity and Mediation in Eighteenth-Century Britain, Minnesota UP, 2018, pp. 1-34.