This post is part of our By Our Books: Bibliography in the WPHP Spotlight Series, which will run through July 2023. This series attends to the bibliographical fields of the WPHP title records, tracing the history of our thinking about our descriptive practices and how they are informed by the sources available to us and by our feminist ambition to recognize and reconstruct women’s labour in print, broadly conceived.

Authored by: Kandice Sharren

Edited by: Michelle Levy and Kate Moffatt

Submitted on: 08/04/2023

Citation: Sharren, Kandice. "The Edition Issue." The Women's Print History Project, 2 August 2023, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/129.

Figure 1. American imprint.

Because they are not constrained by the physical limitations of print, digital bibliographies have the potential to break space-saving conventions. Elsewhere, Michelle Levy, Kate Ozment and I have noted that the medium of the WPHP allows the project to “eschew a key strategy of print bibliography, known as the degressive principle” (893), which, according to Michael F. Suarez, S.J., involves “characterizing variant issues and states—and subsequent impressions too—in lesser detail for the sake of economy” (211). The degressive principle was on display to varying degrees in the two resources I relied on in my first months working on the WPHP: the English Short Title Catalogue (ESTC) and James Raven, Peter Garside, and Raven Schöwerling’s bibliography, The English Novel, 1770–1829. The ESTC is a digital catalogue supported by the British Library; it includes subsequent editions, but often omits some of the detail in full titles and imprints. By contrast, The English Novel is a print bibliography that provides detailed bibliographic information about the first edition of a work, but only lists years and places of publication for subsequent editions. As a digital bibliography, the WPHP has followed the ESTC in capturing multiple editions, but it aims to make the metadata as complete as possible for all editions of a work that appeared within our date range. Identifying and capturing metadata for all of the editions of each work authored by a woman gives us important insight into the relative success of a given work as measured by its longevity in print as well as how its marketing changed over time. It also refuses to privilege first and lifetime editions, and therefore authorial intent and copyright, by giving unauthorized and authorized editions equal weight.

The choice to include all known British, Irish, and American editions requires a working definition of edition that can be consistently applied across the WPHP. G. Thomas Tanselle defines “edition” as “all copies resulting from a single job of typographical composition” (18), and identifies “impressions,” “issues,” and “states” as three possible sub-categories. “Impression” describes “those copies of an edition printed at any one time” (18), while “issue” and “state” refer to the different types of variations that occur “[w]hen alterations, corrections, additions or excisions are effected in a book during a process of manufacture that may continue after publication day” (Carter and Barker 133-4). In particular, “issue” describes a variation that has implications for how we understand the book as a whole, because it has “some connection with the progress of the edition,” including “variant title-pages, usually in respect of the publisher’s imprint” while “state” refers to less momentous changes, such as the insertion of a leaf or an errata list (Carter and Barker 134).

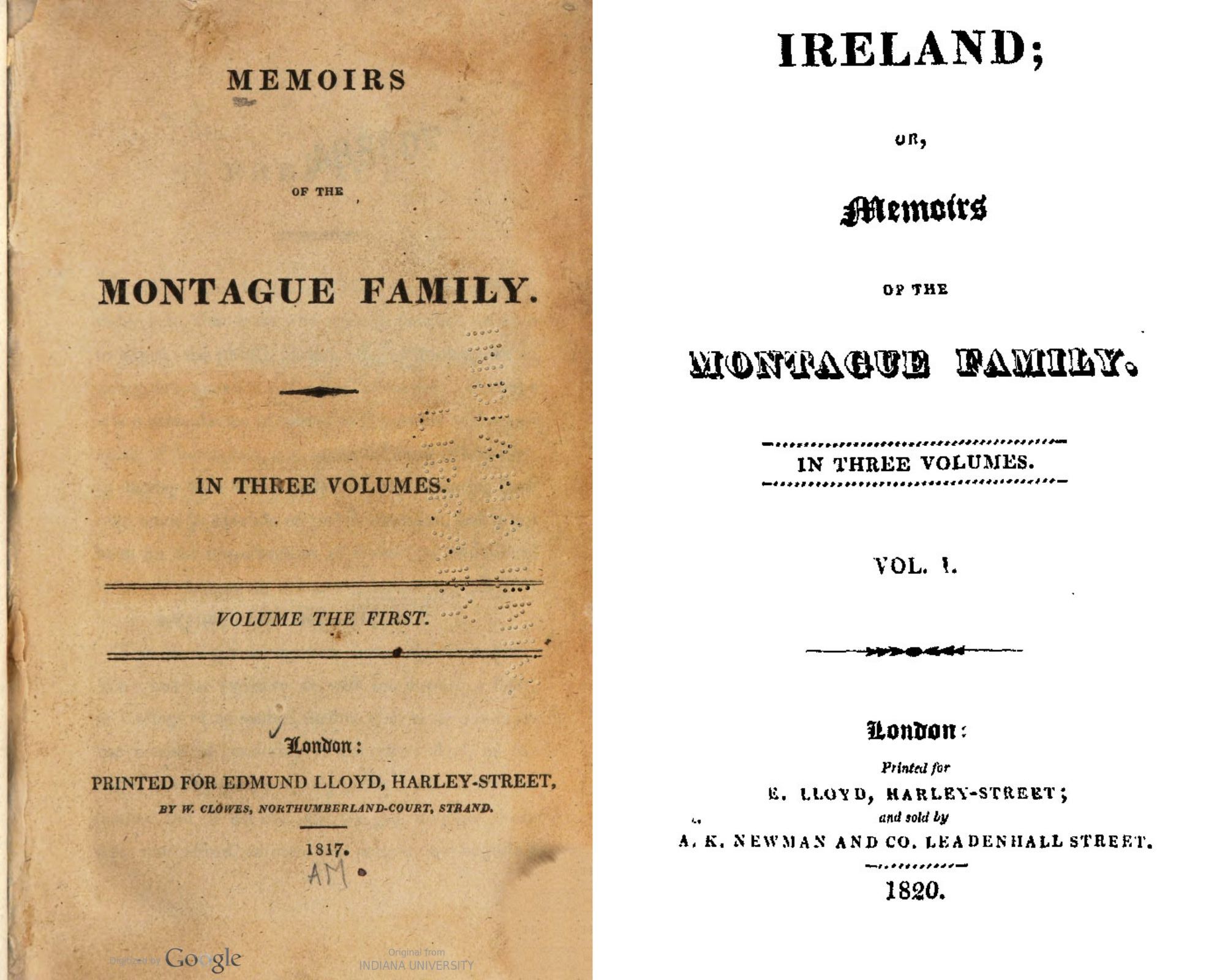

The distinction traditional bibliographers draw between “edition” and “issue” causes practical problems for a project engaged in large-scale bibliography that relies on digital surrogates because it requires detailed examination of the book, with attention to minor differences in typesetting and production. In addition to requiring access to physical copies of all books that appeared in multiple editions, it would simply be too time consuming to go through each of the 16,000-plus titles in the database to ensure we have correctly identified their editions. Instead, we have adopted a policy of what we term “radical descriptiveness,” through which the WPHP “captures as fully as possible information found in the objects of our study—the books themselves—as a means of representing how books appeared to their first readers” (Sharren et al. 893). In the case of tracking editions, this means that we rely on the information in the book itself, especially the title page, to determine the edition. On the rare occasion when a resource identifies what appears to be a new edition as a reissue or a false edition statement, we still create separate records in the database and include that information in the “Notes,” as we did for Alicia Margaret Ennis’s Ireland; or the Memoirs of the Montague Family, an 1820 reissue of remaindered copies of the 1817 first edition. The exceptions to this rule are variant title pages that do not claim to be a distinct edition, as in the case of those noted in the record for Bradford and Inskeep’s 1810 Philadelphia reprint of The Letters of Mrs. Elizabeth Montague.

Figures 2 and 3. Title pages for Alicia Margaret Ennis' Memoirs of the Montague Family, retitled Ireland for the 1820 reissue. HathiTrust and NCCO.

As with the signed author, imprint, and colophon fields, our approach to recording edition information privileges the book-as-object. To capture information about editions, the WPHP relies on two fields: “Edition,” which is a numerical expression of a title’s edition, and “Edition Statement,” a transcription field that records the language used to describe the edition on the title page. These fields came into being to capture some of the ambiguities of how subsequent editions can be identified, after we discovered that a single numerical field was insufficient. While many subsequent editions of a work simply identify themselves as the second or third edition on the title page, which allows us to enter both the numerical “Edition” and the “Edition Statement,” not all editions are identified by a number. Searching for the phrase “new edition” in the “Edition Statement” field brings up 407 results. In these cases, it is difficult to be certain that we have not missed an earlier, numbered edition, so we leave the “Edition” field blank and enter the text into the “Edition Statement” field, as we did for the so-named “new edition” of Maria Susanna Cooper’s The Exemplary Mother that was published in 1784. Unauthorized reprints further challenge our ability to construct a clear chronology of editions. The 1793 Boston edition of The British Album describes itself as the “First American Edition, from the Fourth London Edition.” This title is a rare instance of one that offers us a precise textual genealogy, but does not offer us a straightforward number to enter into the “Edition” field. As with The Exemplary Mother, we leave the “Edition” field blank.

Figure 4. Title page of the first American edition of The British Album (1793), which features an unusually detailed edition statement. Google Books.

Both Ennis’s Ireland; or The History of the Montague Family and The British Album present us with an additional challenge in grappling with editions; they have different titles from their first editions. While the relationship between Ireland; or The History of the Montague Family and the first edition’s title, The History of the Montague Family, is self-evident, The British Album is more challenging. The British Album was originally titled The Poetry of the World when it was published in 1788, but renamed for the second edition in 1790. The second London edition captures this shift by noting that the poems “were originally published under the title of The Poetry of the World” in the full title, but the third and fourth editions—as well as the first American edition—do not, meaning that they would not appear in a search for the original title, although we do note the change in the “Notes” field. One feature that we do not have (yet) is the ability to link editions of the same work, which would allow the relationships between titles to be clear, even when the title changed. Integrating this feature will better allow us to create clear relationships between different editions with different titles, enabling us to explore the changes in how books were represented to the world between their first and subsequent, whether authorized or unauthorized, editions.

As a project, we aim to include all editions of books that women were involved in producing between 1700 and 1836. However, the WPHP continues to be shaped by the degressive principle because it is so embedded in the resources we use. In the podcast episode “Oh, Those Fashionable Burney Novels!” Kate Moffatt and I explore how we discovered that we were missing a number of British editions of Evelina and Cecilia after 1800 simply because they were not identified in any of the resources we had used. We noticed this gap because Frances Burney is a canonical writer, but doubtless there are many other similar cases of works by lesser-known writers. If you notice any editions we are missing, don’t hesitate to let us know!

WPHP Records Referenced

Alicia Margaret Ennis (person, author)

Ireland; or the Memoirs of the Montague Family (title)

The History of the Montague Family (title)

The Letters of Mrs. Elizabeth Montague (title)

"The Language of Authorship" (spotlight)

"'Printed by—': Imprints and Firms in the WPHP" (spotlight)

"Colophons Count" (spotlight by Kate Moffatt)

Maria Susanna Cooper (person, author)

The Exemplary Mother (title)

The British Album (title; first American edition)

The Poetry of the World (title)

The British Album (title; second London edition)

"Oh, Those Fashionable Burney Novels!" (podcast episode)

Works Cited

Carter, John, and Nicolas Barker. ABC for Book Collectors. 8th ed., Oak Knoll Press and The British Library, 2004.

Sharren, Kandice, Kate Ozment, and Michelle Levy. "Gendering Digital Bibliography with the Women’s Print History Project." Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 54, no. 4, 2021, pp. 887–908.

Suarez, Michael F., S.J., “Book History from Descriptive Bibliographies,” The Cambridge Companion to the History of the Book, edited by Leslie Howsam. Cambridge UP, 2015, pp. 199–218.

Tanselle, G. Thomas. "The Bibliographical Concepts of Issue and State." The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, no. 69, Jan. 1975, pp. 17–66.