This post is part of our Black Women's and Abolitionist Print History Spotlight Series, which will run between 19 June and 31 July 2020. Spotlights in this series focus on our work to find Black women who were active participants in the book trades during our period, to acknowledge the ways in which white female abolitionists exploited print’s powerful potential for eliminating slavery, and to revisit the lives and books published by well-known Black female authors.

Authored by: Victoria DeHart

Edited by: Michelle Levy and Kandice Sharren

Submitted on: 07/16/2020

Citation: DeHart, Victoria. "Elizabeth Heyrick, Mother of Immediatism." The Women's Print History Project, 16 July 2020, www.womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/27.

Figure 1. Silhouette Image of Elizabeth Heyrick. Courtesy of The Abolition of Slavery Project.

In 1824, Elizabeth Heyrick published her pamphlet, Immediate, not Gradual Abolition; or, An Inquiry into the shortest, safest, and most effectual means of getting rid of West Indian Slavery, criticizing the leading anti-slavery figures of the day, William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson, for being too "polite" and "accommodating" of enslavers (1824 14). Wilberforce and Clarkson believed that, after the abolition of the slave trade in 1808, slavery in the British Colonies would gradually come to an end, as enslaved people could no longer be replaced through the slave-trade. However, as colonial slavery continued to flourish into the 1820s, more than a decade after the eradication of the trade, Heyrick’s position that colonial slavery too needed to be abolished gained traction. Her pamphlet became an important work in its opposition to the "gradualist abolitionists" and in influencing public opinion to support the cause of immediate abolition. It was widely distributed amongst Anti-Slavery societies and caused much discussion in public meetings in various parts of England and the United States.

Elizabeth Heyrick (1769–1831) was the daughter of John Coltman (d. 1808), a wealthy worsted manufacturer, and Elizabeth Cartwright (1737–1811), a book reviewer and poet. Her parents were dissenters and friends of writers and poets Robert Dodsley, William Shenstone, and John Wesley (Grundy 1). In 1787, Elizabeth Coltman married John Heyrick, a practising lawyer and poet. The marriage was short, as John Heyrick died in 1795. After his death, Elizabeth Heyrick became a Quaker and dedicated herself to writing and activism (The Abolition of Slavery Project). Heyrick has long been confused with another author who shared her maiden name, Elizabeth "Eliza" Coltman (1761–1838), a children's author and writer of a pacifist polemic, The Warning: Recommended to the Serious Attention of all Christians, and Lovers of their Country. Until recently, Heyrick has been given credit for Eliza Coltman's work (Whelan 184).

Studies of Elizabeth Heyrick, particularly those by Clare Midgley and Jennifer Holcomb, have documented the impact she had during the fight for abolition. According to Isobel Grundy, Heyrick drafted at least twenty pamphlets, although many have either been lost or were never printed (Grundy 1); in a biography written on the Coltman family (1895), Catherine Beale references Heyrick’s “mass” of unpublished material (215). So far, we have found 6 separate pamphlets, and six editions of Immediate, not Gradual, Abolition. Heyrick's pamphlets concern a wide variety of issues beyond abolition including animal cruelty (1809; 1823), corporal punishment (1827), and advocacy for higher wages and better working conditions for factory workers (1817) (Grundy 1). She is, however, best known for her uncompromising advocacy on behalf of immediate abolition during the 1820s.

Heyrick’s activism was spurred by her involvement in The Anti-Slavery Society (1823–1839) an organization dedicated to the eradication of slavery throughout the British Empire (Holcomb 89). Thomas Clarkson (1760–1846) and William Wilberforce (1759–1833) were in leading positions, but the society was split into two groups, those in favour of gradual abolition and those in favour of immediate action. Heyrick joined the group in 1823 and fell into the latter category.

Elizabeth Heyrick was instrumental in the formation of the Female Society of Birmingham in 1825, as well as the Leicester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society (Rappaport 295). The Female Society of Birmingham sought to deliver direct support to enslaved women in the West Indies and boycott products produced from slave-labour (Holcomb 97). In Leicester, she organized a sugar boycott and urged grocers not to stock West Indian imports. Heyrick personally campaigned with the pamphlets in hand, visiting door to door, house to house. By 1825, roughly twenty-five per cent of Leicester's population had stopped buying sugar (Grundy 1).

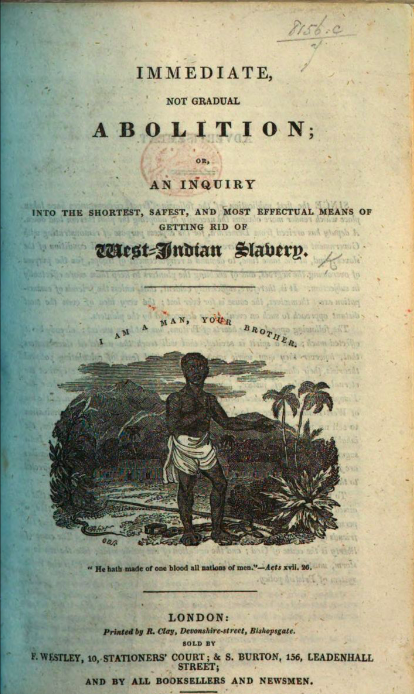

Figure 2. First Edition of Immediate, not Gradual, Abolition (1824). British Library.

In 1824, Immediate, not Gradual Abolition was “hurled like a bomb in the midst of battle” (Ware 71). Heyrick writes: “The perpetuation of slavery in our West India colonies, is not an abstract question, to be settled between the Government and the Planters,—it is a question in which we are all implicated;—we are all guilty” (1824, 4). She criticises Wilberforce and Clarkson for being too "slow and cautious” (1824, 14) and she denounces “the government for negotiating with slave-holders” (Ware 72). The pamphlet rattled the Anti-Slavery Society and caused much debate within it. Wilberforce and the other gradualists were stunned by Heyrick and tried to suppress the distribution of her pamphlet (Rappaport 296). So agitated was Wilberforce, he ordered the other leaders of the abolition to ignore women’s anti-slavery societies as many of them supported Heyrick’s ideas (The Abolition of Slavery Project). The pamphlet "signalled an important shift in the abstention movement as Heyrick linked the boycott of slave labour to the immediate abolition of slavery and the granting of civil rights to freed slaves" (Holcomb 90). Many of the women’s anti-slavery societies followed Heyrick’s lead and boycotted sugar in cities around the United Kingdom, including London, Edinburgh, Worcester, and Colchester (Rappaport 296).

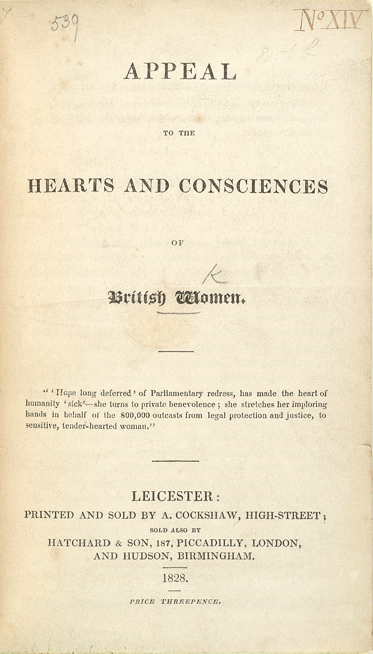

Figure 3. Title page of Appeal to the Hearts and Consciences of British Women (1828), courtesy of The British Library.

Heyrick published a second anti-slavery polemic, Appeal to the Hearts and Consciences of British Women in 1828, as a direct plea for women to join the cause. She writes that women are particularly qualified "not only [to] sympathize with suffering, but also to plead for the oppressed" (1828, 3). Heyrick's writing had a clear impact, as by 1830 over seventy women's anti-slavery societies were established across the United Kingdom, many of them calling for immediate action and putting further pressure on the gradualists (Holcomb 97). Other female leaders of these groups included Anne Knight in Chelmsford, Mary Lloyd in Birmingham, and Amelia Opie in Norwich; their works are found in the database.

The Anti-Slavery Society relied heavily on women’s groups for financial support, with the largest donation coming from The Female Society of Birmingham (Rappaport 296). The Female Society of Birmingham became one of the most prominent women’s anti-slavery groups in England and directed twenty other smaller anti-slavery factions (Holcomb 97). In 1830, Heyrick and The Female Society of Birmingham threatened to withdraw funds unless the Anti-Slavery Society agreed to immediate abolition. It was a successful endeavor, as by May, 1830 the Anti-Slavery Society became devoted to immediatism (Rappaport 296).

Immediate, Not Gradual Abolition was initially published anonymously in London, as were the second and third editions published later in the same year. Hundreds of thousands of copies of the pamphlet were sold and circulated across Britain (Hochschild), and it proved to be Heyrick’s most influential work (Midgley 102). Through her Quaker connections, the pamphlet reached the United States and left a lasting impression (Rycenga 40). Jennifer Rycenga believes it was first published in 1825 in America, after it was picked up by fellow Quaker abolitionist Benjamin Lundy and quickly circulated through Quaker communities (40). The earliest American edition we have in the database dates to 1836, but we know that it was circulating well before then.

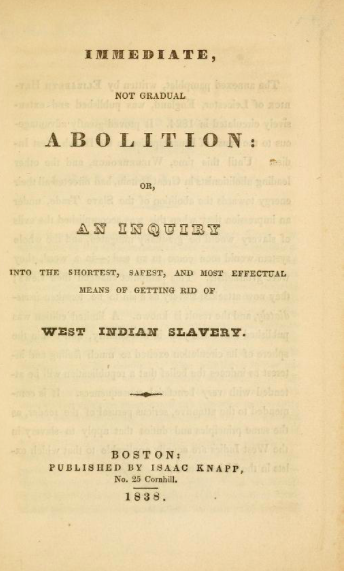

Figure 4. Title page of Immediate, not Gradual, Abolition (1838). Internet Archive.

Immediate, Not Gradual Abolition inspired activists on both sides of the Atlantic. The pamphlet became popular in the United States and several editions were published in the 1830s (1836, 1837, 1838). Prominent American abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison, Lucretia Mott, and Frederick Douglass admired her work (Rappaport 296). Interestingly, the American printers and publishers chose to attach Heyrick’s name to the pamphlet and also added further information concerning its impact in Britain and on the leaders of the Anti-Slavery Society. Several American editions state in the preface to the pamphlet that it:

proved greatly advantageous to the cause of Emancipation in the British West Indies. Until this time, Wilberforce, and the other leading abolitionists in Great Britain, had directed all their energy towards the Abolition of the Slave Trade . . . this pamphlet changed their views; they now attacked slavery as a sin to be forsaken immediately and the result is known . . .

Elizabeth Heyrick was one of the most prominent radical women activists of the 1820s yet she is little known today. She was instrumental in changing public opinion, in shifting the minds of abolitionists, as well as in spurring the end to colonial slavery. Rycenga writes that "before [Heyrick], most writers opposed to slavery were white men of education and privilege, as well as unabashed, self-acknowledged gradualists" (Rycenga 40). They lacked the persuasiveness and rhetoric Heyrick was able to conjure in her writing. Sadly, like Wilberforce—the abolitionist whose mind she changed and who is far better known today—Elizabeth Heyrick died in 1831, two years before the passing of the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 which abolished slavery throughout the British empire.

WPHP Records Referenced:

Heyrick, Elizabeth (person, author)

Immediate, not Gradual, Abolition: or, An Inquiry into the shortest, safest, and most effectual means of getting rid of West Indian Slavery (title, first London edition)

Dodsley, Robert (person, author)

Shenstone, William (person, author)

Wesley, John (person, author)

Coltman, Elizabeth "Eliza" (person, author)

The Warning: Recommended to the Serious Attention of all Christians, and Lovers of their Country (title)

Bull-Baiting: a Village Dialogue, Between Tom Brown and John Sims (title)

Appeal to the Hearts and Consciences of British Women (title)

Knight, Anne (person, author)

Lloyd, Mary (person, author)

Opie, Amelia (person, author)

Immediate, not Gradual, Abolition: or, An Inquiry into the shortest, safest, and most effectual means of getting rid of West Indian Slavery (title, second London edition)

Immediate, not Gradual, Abolition; or, An Inquiry into the shortest, safest, and most effectual means of getting rid of West Indian Slavery (title, 1836 American edition)

Immediate, not Gradual, Abolition, By Elizabeth Heyrick, a Member of the Society of Friends (title, 1837 American edition)

Immediate, not Gradual, Abolition; or, An Inquiry into the shortest, safest, and most effectual means of getting rid of West Indian Slavery (title, 1838 American edition)

Works Cited

“Elizabeth Heyrick (1769-1831): The Radical Campaigner.” The Abolition of Slavery Project, 2009 http://abolition.e2bn.org/people_31.html.

Beale, Catherine Hutton. Catherine Hutton and her Friends. Cornish Brothers, 1895.

Grundy, Isobel. "Heyrick, Elizabeth (1769-1831)." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1093/odnb/9780192683120.013.37541.

Heyrick, Elizabeth. Immediate, not Gradual, Abolition: or, An Inquiry into the shortest, safest, and most effectual means of getting rid of West Indian Slavery. 1st ed. Richard Clay, 1824.

Hochschild, Adam. “The Unsung Heroes of Abolition: Elizabeth Heyrick.” BBC, 2011, http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/abolition/abolitionists_gallery_08.shtml.

Holcomb, Julie L. “I am a Man, Your Brother: Elizabeth Heyrick, Abstention, and Immediatism.” Moral Commerce: Quakers and the Transatlantic Boycott of the Slave Labour Economy. Cornell P, 2016, pp. 89–106.

Midgely, Clare. Women Against Slavery: The British Campaigns, 1780-1870. Routledge, 1992.

Rappaport, Helen. Encyclopedia of Women Social Reformers, vol. 1, ABC-Clio, 2001.

Rycenga, Jennifer. “A Great Awakening: Women's Intellect as a Factor in Early Abolitionist Movements, 1824-1834.” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, vol. 21, no. 2, 2005, pp. 31–59.

Ware, Vore. White Women, Racism, and History. Verso, 2015.

Whelan, Timothy. Other British Voices: Women, Poetry, and Religion, 1766-1840. Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Further Reading

Hochschild, Adam. Bury the Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire’s Slaves. Macmillan Publishers, 2005.

James, Felicity, and Rebecca Shuttleworth. “Susanna Watts and Elizabeth Heyrick: Collaborative Campaigning in the Midlands, 1820-34.” Women's Literary Networks and Romanticism: ‘A Tribe of Authoresses,’ edited by Andrew O. Winckles and Angela Rehbein, Liverpool UP, 2017, pp. 47–72.

Zoellner, Tom. “How One Women Pulled Off the First Consumer Boycott - and Helped Inspire the British to Abolish Slavery. The Conversation, 10 July, 2020. https://theconversation.com/how-one-woman-pulled-off-the-first-consumer-boycott-and-helped-inspire-the-british-to-abolish-slavery-140313.