This post is part of our Women & History Spotlight Series, which will run through March 2021. Spotlights in this series focus on women's contributions to history in the database.

Authored by: Caelen Campbell

Edited by: Michelle Levy and Kandice Sharren

Submitted on: 03/26/2021

Citation: Campbell, Caelen. "Charlotte Turner Smith’s A Natural History of Birds Intended Chiefly for Young Persons." The Women's Print History Project, 26 March 2021, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/69.

Figure 1. Title page for the 1819 edition of Charlotte Turner Smith’s A Natural History of Birds Intended Chiefly for Young Persons.

Our late conferences on various subjects of Natural History have awakened your curiosity, my children, and as you wish to hear more of the varieties of birds, their habits, and history, I will communicate the observations I have made, and consult the books I have about me, and endeavour to give you a general idea of these animals. (1:1)

In 1807, the year after Charlotte Turner Smith's death, A Natural History of Birds Intended Chiefly for Young Persons was first published in London by Joseph Johnson. A second edition published in 1819 by John Arliss, John Bumpus, and John Sharpe includes on its boards options for a copy embellished with 24 engravings (7S) or with the plates coloured (9S). Published in two volumes, this ornithology handbook seeks to interest her child readers in natural history. It provides Smith with an avenue to intertwine mythology and literature, enjoyed by many children, with deep scientific understanding. Placing this importance on children being fluent in literature, mythology, and history in concurrence with an education in science and the natural world supports a whole-child approach to education, where learning looks to formal study to support the personal acquisition of knowledge. As a mother of ten children (eight of whom survived into adulthood), Smith used the experience she gained from teaching her own children to successfully enter new literary markets, publishing four works for children: Rural Walks (1795), Rambles Farther (1796), Minor Morals (1798), and Conversations Introducing Poetry (1804). In the preface to A Natural History of Birds, the editor includes a description of her writing for children by one of her biographers, who praises “her schoolbooks [as] among the most admirable which have been written for the use of young persons and are eminently calculated to form the taste, instruct the mind, and correct the heart” (1:v). Smith’s poetic descriptions of the natural world possess the exactitude of a naturalist’s field notes, combined with the comforting idea of inheriting knowledge from one’s mother. The central role that mothers played in the education of their young children is explored in podcast episode four of The WPHP Monthly Mercury, "A Bibliographical Education," where WPHP editors Kandice Sharren and Kate Moffat are joined by Reese Irwin, a former Research Assistant, to talk about the children’s literature in the database.

In A Natural History of Birds, Smith uses Carl Linnæus’ system for organizing birds into six Orders. She includes a letter to describe each Order or portion of an Order under this system. The letters are written by Smith to one of her two sons, and she uses the epistolary form to create a domestic, conversational frame to introduce her children (and her child readers) to the six orders of birds, which are as follows: Accipetres (birds of prey), in letters I and II; Pica (compressed, convex, and mostly crooked bills), in letters III and IV; Anseres (web-footed), in letter V; Grallae (waders), in letter VI; Gallinae (domestic foul), in letter VII; and Passeres (singing birds), in letters VIII, IX, and X; it is treated in three letters as it is the “most interesting order of birds” (1:22). Since she wishes to impart knowledge to an exacting standard, yet considers herself a “very humble student in botany,” Smith selects Linnæus as “the most simple” organizing principle, making her presentation of natural history accessible to children (2:23). This choice is interesting given the rising controversy in England at the time over Linnæus’ Sexual System or systema sexuale of botanical classification, which made use of human–plant analogies, and thus was deemed improper for women wishing to study botany (George 1). There were equally avid proponents who insisted on women’s continued access to Linnæan knowledge; one of these was Mary Wollstonecraft, who defended botany against prudery in her A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects (George 6). Smith had utilized Linnæus in her previous botany poems, so it follows, she would here, however, her descriptions are notably desexed and contain few human analogies.

Following the pattern which she laid out for herself, Smith selects a set of birds to describe in each order. For example, for the first order of Accipetres, she includes the Eagle and details its physical appearance, its diet, and hunting habits. Her descriptions are meant to engage her readers; describing how the eagle “has been known to bear away an infant in its talons, kids, lambs, hares and rabbits are its usual food, so that it is very injurious to the people of the countries it inhabits'' (1:11). Some observations derive from personal knowledge, whereas others are taken from the literature of naturalists and travel writers. Within these descriptions, there are distinctly tactile observations and experiences which hint at the influence of John Locke’s pedagogical innovations and educational theories at the time; that children are born as an blank slates, or tabula rasa, to be filled with the data derived from sensory experience (Androne 75-76). Applying tactile explorations to poetry models how to relate to natural history on a personal level, aiming to transmit the active experience and knowledge of observation through natural description (Powell 101). This inclusion of first-hand observations continues to be practiced in education, for example with the use of interpersonal dialogues to garner relatability so as to entice children into learning. As her studies in this book are mainly about birds in Britain, applying the popular botany practice of ‘indigenous botany,' her young readers would have felt excited that they could observe the species she describes themselves (George 7). Smith also includes bibliographic references in the descriptions to additional natural resources, some of which may have been available to her readers, such as Conversations on Natural History. Afterwards, she expands her scientific understanding with the inclusion of Greek and Roman mythology and history. An example of this use of mythic explanation is apparent in references to The Odyssey of Homer (as translated by William Cowper), in her description of the Eagle.

Figure 2. Excerpt from Charlotte Turner Smith’s A Natural History of Birds Intended Chiefly for Young Persons, 1819 (1:15).

This engaging pattern is repeated throughout the two volumes, as Smith cites many poets, including contemporary poets like Erasmus Darwin, James Thomson, and William Wordsworth, and earlier poets, including John Milton and William Shakespeare. Before each excerpt, Smith indicates why she feels the myth or poem deserves a place in her telling of natural history. When Smith was unable to find a fable or a myth on a specific bird which she felt was of particular importance, she instead includes her own sonnet or fable to instruct, teach, and guide children. For example, she explains that she knows of no one who has spoken about the "Jar bird, or Churn owl" (a local British name of the European goatsucker or night-jar, Caprimulgus europæus), and so adds a few lines from a sonnet by "an acquaintance of yours," that is, herself; the page may be seen below (1:95) “The Lark’s Nest” she includes as her “version of a fable from Esop”[sic] which she “dressed with a few botanical ornaments” that the reader will “allow to be an improvement” (2:37). She states: “I hope you will be pleased with this fable. I know none which goes more immediately to the business and bosoms of all who are likely to have an active part in the affairs of the world” (2:38). Included in this text are five bird epics, “The Dictatorial Owl,” “The Jay in Masquerade,” and three additional poems, “The Truant Dove,” “The Lark’s Nest,” and “The Swallows,” which were concurrently published in her posthumously published poem, "Beachy Head." “The Swallows,” titled “To The Swallow” in A Natural History of Birds, uses the “full range of discourses available at the end of the eighteenth century for representing nature: scientific description, poetic conventions of personification and apostrophe, the pastoral thematization of music, a miniature topographic survey, the fable, Ovidian allusions, folklore, and God” (Cook 67).

Figure 3. Excerpt from Charlotte Turner Smith’s A Natural History of Birds Intended Chiefly for Young Persons, 1819 (1: 95).

Her first-person interjections in her letters are often socially or morally corrective, but they are also witty, pulling the reader in to enjoy her clever descriptions. For example, there is the white owl, who

has a look of affected wisdom, as it sits with half-closed eyes, dreaming on it’s roost all day; but when it is alarmed, or eager for food, and opens those round staring eyes, it gives an idea of folly. There are human faces extremely resembling that of this bird; and I think I have observed, that such faces indicate no great strength of intellect, but much of presumption and self conceit. (1:27)

Or the description “of pertness and importance in the air of a Jay, when he rears the feathers of his head and looks about him, as if he supposed himself a bird of considerable consequence, and was conscious of his beauty” (1:50). There are also times where her political and social beliefs are introduced through the bird lessons to teach children about social concerns of the time. When speaking about parrots, she observes that “the poets have sometimes compared their loquacity and their speaking only by rote to that desire of talking without having anything to say worth being heard which these satyrists impute to women”; he states that she hoped to include poetry to refute this insulting claim, but could find none “that had the merit of being well written,” speaking again to her exacting standards (1:38). Or in her retelling of the fable of the Goose that laid the Golden Egg, about a man who destroys a goose who foolishly and greedily destroys his goose who lays golden eggs, she relates it to other atrocities, of animal abuse and slavery:

A horse is sometimes overworked by his barbarous owner, that he may make all the present profit he can of him; and the same thing has, I fear, been done in those countries where the unhappy negroes are purchased, and compelled to labour to raise sugar, and coffee, and cotton, for the use of Europeans.(1:107)

Figure 4. Plate from Charlotte Turner Smith’s A Natural History of Birds Intended Chiefly for Young Persons, 1819 (1:31).

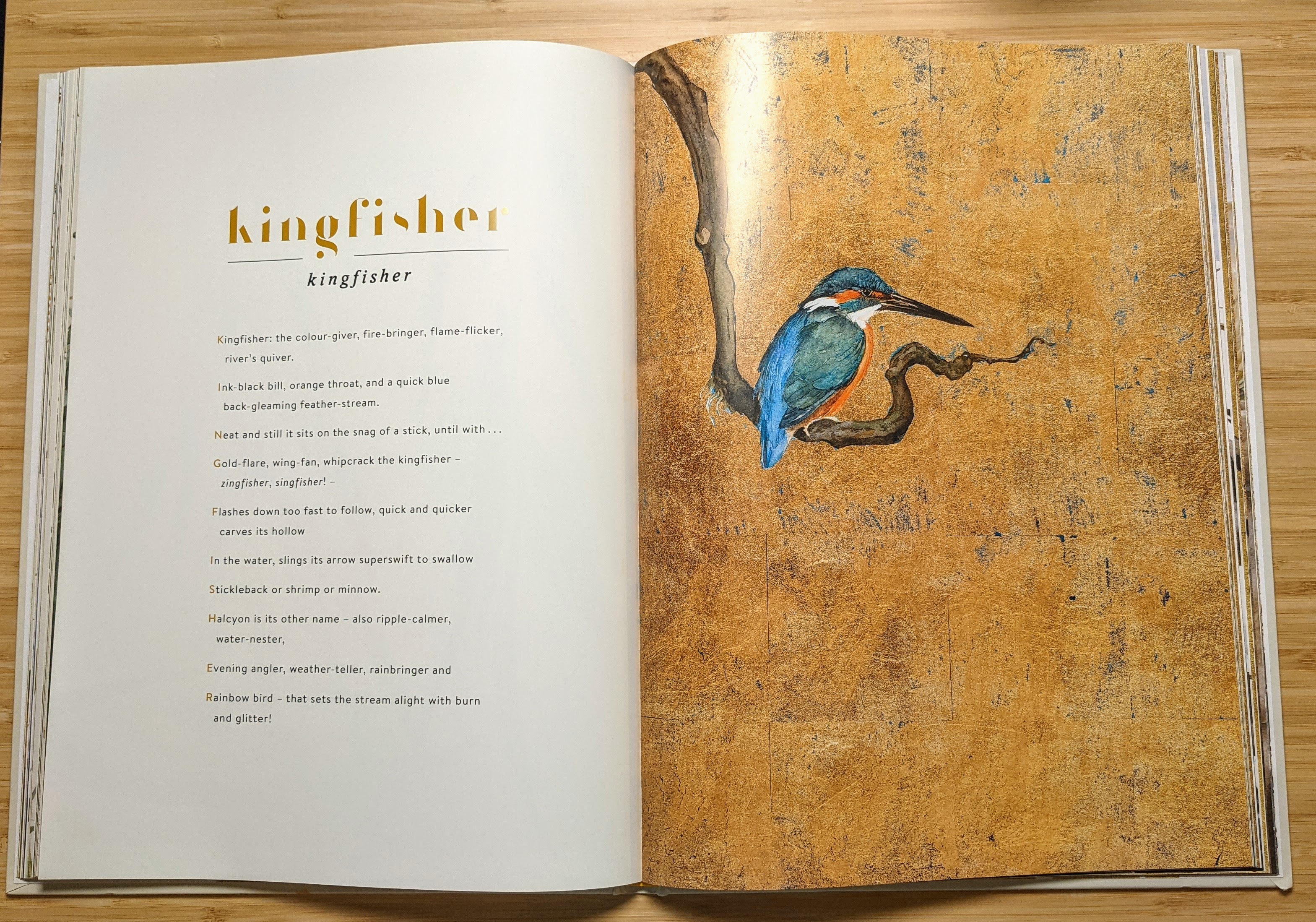

Smith’s style of linking the natural world to poetry is a strategy that has been adopted by contemporary authors. There has recently been an impetus of rewilding children to the natural world, asking them to focus inwards, mindfully, on the smaller details within their control, while also increasing their knowledge of the natural world. This direct engagement with the natural world is the goal of Robert McFarlane and Jackie Morris’s picture book, The Lost Words: A Spell Book, published in 2018. The large 15-inch book offers beautiful illustrations of the language of the natural world, a vocabulary they fear is being lost. The book was spurred by the actual removal of some forty words, names of animals and plants, from the Oxford Junior Dictionary. McFarlane and Morris follow the same idea as Smith in their book; defining an animal through poetry, in their case acrostic poetry, to make it readily accessible to children. The poems themselves follow the pattern that Smith laid out in her descriptions; detailing their physical attributes, their eating habits, and their interactions in the world in a way that emulates direct observation. As the second edition used plates to add life and intrigue to Smith’s explanations, McFarlane and Morris use full-page illustrations, which show the animals moving through the pages, as they would in nature, leading the reader from one poem to the next.

Figure 5. The Lost Words: A Spell Book by Robert McFarlane and Jackie Morris (65–66).

WPHP Records Referenced

Smith, Charlotte Turner (person, author)

Johnson, Joseph (firm, publisher)

Arliss, John (firm, publisher and printer)

Bumpus, John (firm, publisher)

Sharpe, John (firm, publisher)

Wollstonecraft, Mary (person, author)

A natural history of birds: intended chiefly for young persons (title, 1807 edition)

A natural history of birds: intended chiefly for young persons (title, 1819 edition)

A vindication of the rights of woman: with strictures on political and moral subjects (title)

Beachy Head: with Other Poems, by Charlotte Smith. Now first published (title)

The WPHP Monthly Mercury: Episode 4, "A Bibliographical Education" (podcast)

Works Cited

Andron, Mihai. “Notes on John Locke's Views on Education.” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, vol. 137, 2014, pp. 74–79.

Cook, Elizabeth Heckendorn. “Charlotte Smith and ‘The Swallow’: Migration and Romantic Authorship.” Huntington Library Quarterly, vol. 72, no. 1, 2009, pp. 48–67.

George, Sam. Botany, Sexuality and Women's Writing, 1760–1830: From Modest Shoot to Forward Plant. Manchester UP, 2007.

Powell, R. M. “Linnaeus, Analogy and Taxonomy: Botanical Naming and Categorization in Erasmus Darwin and Charlotte Smith.” Philological Quarterly, vol. 95, no. 2, 2016, pp. 101–24.

Smith, Charlotte. The Letters of Lady Arbella Stuart, edited by Stuart Curran, Oxford UP, 1993.

Zimmerman, Sarah. “Smith [née Turner], Charlotte (1749–1806).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford UP, 2007, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/25790.

Zimmerman, Sarah. “Charlotte Smith's Letters and the Practice of Self-Presentation.” The Princeton University Library Chronicle, vol. 53, no. 1, 1991, pp. 50–77.