This post is part of our Women & History Spotlight Series, which will run through March 2021. Spotlights in this series focus on women's contributions to history in the database.

Authored by: Michelle Levy

Edited by: Kandice Sharren

Submitted on: 04/02/2021

Citation: Levy, Michelle. "Lucy Aikin, Feminist History, and the ‘sisterhood of womankind.’" The Women's Print History Project, 2 April 2021, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/70

Figure 1. Lucy Aikin. Portrait is reproduced with the kind permission of Hampstead Parish Church, and the Rev. Stephen Tucker.

Figure 1. Lucy Aikin. Portrait is reproduced with the kind permission of Hampstead Parish Church, and the Rev. Stephen Tucker.

In 1810, at the age of twenty-nine, a woman published a 1200 line, epic poem that sought to challenge centuries of hateful representations of women, from Juvenal’s Satire VI (late first or early second century), which attacks women as unchaste ‘monsters,’ to John Milton's Paradise Lost (1667), which presents Eve as responsible for the Fall and insists that woman were made by God to serve man, to Alexander Pope’s “Epistle II: To a Lady—Of the Characters of women” (1735), which bluntly asserts that “Most Women have no Characters at all.” The woman who wrote this poem, Lucy Aikin (1781–1864), is far less known that her radical counterparts, Mary Wollstonecraft (whose novel Maria, Or the Wrongs of Woman was the subject of a previous spotlight, “Mary Wollstonecraft and the Domestic Gothic Novel”) and Mary Hays (the subject of a spotlight for this Women’s History Series by Amanda Law, “Taking Up the Cause: Mary Hay’s Female Biography”). Yet in her refutations of interpretations of the Bible and her history of women, Aikin strikes at the heart of Western civilization’s foundational patriarchy. In her introduction to the poem, she writes “that it is impossible for man to degrade his companion without degrading himself,” and points to this as “the chief ‘moral of my song,’” regarding it “as the Great Truth to the support of which my pen has devoted itself” (Epistles 54). It is as though Aikin had in mind Jane Austen’s quotation from Persuasion, as discussed in the introduction to this spotlight series. Aware that the stories told about women had been “‘all written by men,’” she takes up her own pen to rewrite women’s history.

Aikin’s boldness, and her confidence in the righteousness of her undertaking, may be traced to her upbringing in a highly educated, liberal-minded, and well-connected family of Dissenters. Her father, Dr. John Aikin (1747–1822), was a medical doctor and writer who published extensively on literature, education, biography and topography and edited several major periodicals. Her aunt, Anna (Aikin) Barbauld (1743–1825), was a famous poet, essayist, editor, literary critic and children’s writer. In an essay from March 1798, “What is Education?” Barbauld articulated the belief that education “includes the whole process by which a human being is formed to be what he is, in habits, principles, and cultivation of every kind,” noting to the father whom she is addressing, “Your example will educate him; your conversation with your friends; the business he sees you transact; the likings and dislikings you express; these will educate him” (McCarthy, Selected Poetry and Prose 322–23). Aikin attributed her passion for history to her father: “I can speak with all the certainty of personal experience to the pleasures and benefits derived to his family from his social and communicative habits of study” (Epistles 17). She describes how she became a writer and an historian by “witnessing so closely the progress of various works” that her father was engaged in researching and writing; furthermore, her father “not only permitted, but invited and encouraged, the freest strictures even from the youngest and most unskillful of those whom he was please to call his household critics” (Epistles 17–18). Her father and aunt’s Evenings at home; or, the juvenile budget opened. Consisting of a variety of miscellaneous pieces, for the instruction and amusement of young persons, published between 1792 and 1796 when Aikin was herself between the ages of 11–15, models this form of critical and indeed radical education. In these miscellaneous pieces, as with Aikin herself, children are ‘invited and encouraged’ to exercise their own critical judgment.

Aikin’s first publication, Poetry for Children. Consisting of Short Pieces, to be Committed to Memory. Selected by Lucy Aikin, appeared in 1801. Thereafter, she published in many different genres: she wrote a novel, poems, translations, biographies, collections of various kinds for children, and reviews, and also edited her aunt’s poetry and prose. It is her historical writing, however, for which she became best known. This writing came in two bursts, and in two different genres. In 1810, at the age of twenty-nine, she published Epistles on the Character and Condition of Women, in Various Ages and Nations; it was reprinted the same year in Boston. It is “the first text in English to rewrite the entire history of western culture, from the account of creation in Genesis through the eighteenth century, from a feminist perspective, explicitly defining the practices and consequences of a patriarchal social system” (Epistles 13). Her second and more extended engagement with history came in the genre she popularized in England, called the court memoir. In 1818, she published Memoirs of the Court of Queen Elizabeth, to be followed Memoirs of the Court of King James the First in 1822, and Memoirs of the Court of Charles the First in 1833. These Memoirs were critically acclaimed and popular: Memoirs of the Court of Queen Elizabeth went through six London editions by 1826, was translated into German in 1819, and reprinted in Boston in 1821; Memoirs of the Court of King James the First reached a second edition in 1822, and was published that year in Boston; Memoirs of the Court of Charles the First reached a second edition in 1833, and was published in Philadelphia that year. Other editions may well exist, but we have not been able to verify them.

First in her Epistles on Women and then in her Memoirs of the Court of Queen Elizabeth, Aikin displayed an investment in women’s history. The Epistles offers Aikin’s attempt, as she explains in her introduction, to “mark the effect of various codes, institutions, and states of manners, on the virtue and happiness of man, and the concomitant and proportional elevation or depression of woman in the scale of existence” (Epistles 53). Directly responding to misogynist histories and educational writing of her day, Aikin attempts nothing short of an exposé of the history of patriarchy, demonstrating that the systematic oppression of women occurs across all “ages and nations,” stemming from the physical dominance of men and their abuse of power. Divided into four Epistles, each prefaced by an “Argument” that echoes one of the key works she seeks to refute—John Milton’s Paradise Lost—the ambition of the poem is staggering.

In Epistle I, Aikin specifically addresses Milton’s interpretation of the Bible, especially Genesis. In Aikin’s version, derived from the Priestley source, Eve is born from the earth, not Adam’s rib, and it is not Eve who is responsible from the expulsion from the Garden of Eden (after succumbing to temptation and eating the apple). Rather, Adam and Even co-exist in harmony until fighting erupts between their children, Cain and Abel. According to Shirley F. Tung, “Aikin’s epic poem challenges the biblical origins of female subordination by offering an alternative exegesis of Genesis,” using “her considerable scriptural knowledge to contest Eve’s culpability in the Fall, thereby refuting the religious pretext for women’s subjugation” (179).

In Epistle II, Aikin surveys how women, across time and space, have been degraded by men. She invites her friend, Anna Wakefield, to whom the Epistles are dedicated, to join her as she journeys to “Pierce every clime, and search all ages through; / Stretch wide and wider yet thy liberal mind, / And grasp the sisterhood of womankind” (Epistles 61). Here Aikin uses existing historical and anthropological sources to document how women are universally abused by men. Her use of these sources at once establishes her extensive research (she explains how “a large collection has been placed under the eyes of the author, partly by the liberality of her publishers, partly by the kindness of friends,” Epistles 102), but also the prejudices that inevitably permeate the Epistles. She offers accounts, based on the writings of explorers, of “Savage Man,” repeating Eurocentric accounts of so-called ‘primitive’ societies. She does, however, seek to demonstrate that women are victimized by the brutality of all societies. Indeed, we find a very early, and flawed, example of intersectional feminism in Aikin’s attempt to describe and unite a “sisterhood of womankind.”

Epistle III concerns itself with classical civilization, that is, with Greek, Trojan and Roman history and myth, to explore the destructive consequences of militarism and violence to women and children. The final Epistle covers the Christian era, from the birth of Christ to Aikin’s own time. She finds one example of a more just and equal society, in the German Goths described in Tacitus’s Germania, a book her father had translated. She identifies other European and English woman who embodied the values she celebrates, the domestic affections and moral virtue, but observes the continued oppression of women in her country and indeed, across the globe. In the end, she invites her countrymen, “the Sons of Albion,” to “be generous then, unbind / Your barbarous shackles, loose the female mind” (Epistles 98–99). As Kathryn Ready has observed, the Epistles presents one of the most startling attempts to begin “the crucial process of dismantling ... patriarchal versions of the past” (450).

Aikin’s engagement with history continued in her three court memoirs, a genre that had been very popular in France but only recently imported to Britain. Aikin herself offers the best description of this genre and explanation of its value, in her Preface to Memoirs of the Court of Queen Elizabeth:

In the literature of our country, however copious, the eye of the curious student may still detect important deficiencies.We possess, for example, many and excellent histories, embracing every period of our domestic annals;—biographies, general and particular, which appear to have placed on record the name of every private individual justly entitled to such commemoration;—and numerous and extensive collections of original letters, state-papers and other historical and antiquarian documents;—whilst our comparative penury is remarkable in royal lives, in court histories, and especially in that class which forms the glory of French literature,—memoir.

To supply in some degree this want, as it affects the person and reign of one of the most illustrious of female and of European sovereigns, is the intention of the work now offered with much diffidence to the public.

Its plan comprehends a detailed view of the private life of Elizabeth from the period of her birth; a view of the domestic history of her reign; memoirs of the principal families of the nobility and biographical anecdotes of the celebrated characters who composed her court; besides notices of the manners, opinions and literature of the reign. (Epistles 101–02)

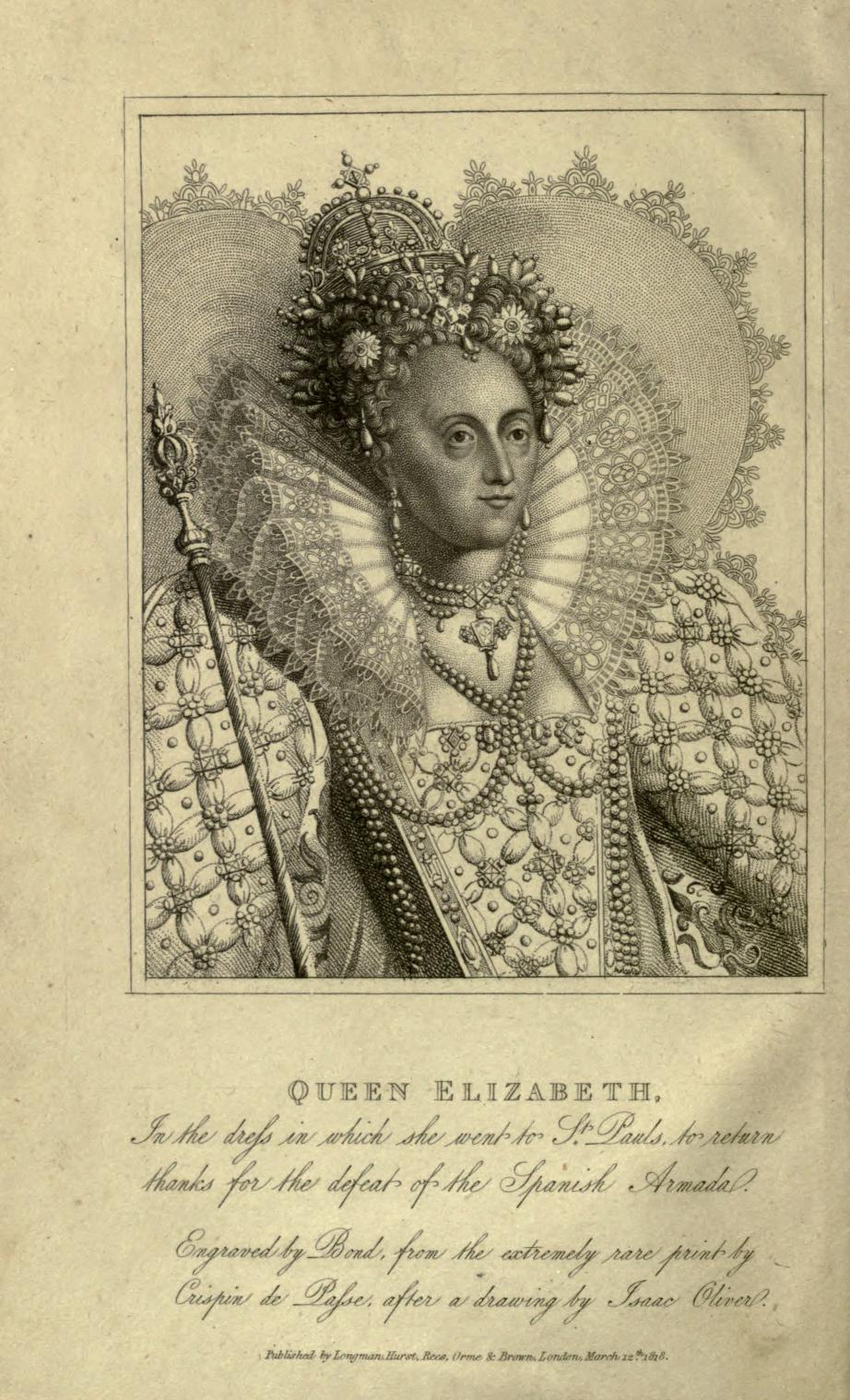

Figure 2. Frontispiece, first edition, The Memoirs of the Court of Queen Elizabeth, 1818.

The mode of the court memoir provided Aikin with an opportunity to delve into the character and even the psyche of England’s most important Queen, but also to survey “the manners, opinions and literature of the reign,” a form of social and literary history for which he had a particular talent. Aikin professes to “avoid[] as much as possible all encroachments on the peculiar province of history” (Epistles 103), but events of major historical significance during the course of Elizabeth’s reign are not ignored, rather, they are given new life through her method of storytelling as memoir. Arguably, the form of history that Aikin tells is a particularly feminist one, as she considers private feeling and social interactions as shaping forces in history.

Figure 3. Frontispiece, third edition Memoirs of the Court of Queen Elizabeth, 1819.

One example will have to suffice to demonstrate the particular attributes of Aikin’s historical method. In the following passage, Aikin describes, perhaps imagines is more accurate, Elizabeth upon her return to the Tower of London for her coronation, following the death of her sister, Mary I, in 1558:

With what vivid and what affecting impressions of the vicissitudes attending on the great must she have passed again within the antique walls of that fortress once her dungeon, now her palace. She had entered it by the Traitors’ gate, a terrified and defenceless prisoner, smarting under many wrongs, hopeless of deliverance, and apprehending nothing less than an ignominious death. She had quitted it, still a captive, under the guard of armed men, to be conducted she knew not whither. She returned to it in all the pomp of royalty, surrounded by the ministers of her power, ushered by the applauses of her people; the cherished object of every eye, the idol of every heart. (Epistles 110)

In this passage, we find novelistic elements, in both the colourful scene setting and the narrative invitation to share in Elizabeth’s feelings in her reversal of fortunes. We also see how this form of history was one that Aikin, with her acute powers of observation and empathetic imagination, was particularly suited to write. An effusive review from the Gentleman’s Magazine from July 1818 demonstrates the high estimation in which her histories were received:

We are at a loss whether we should most approve the plan, or admire the execution, of this attractive work, the most complete in its kind of any in the English language. The history of Elizabeth has been often written but never in a manner to satisfy the inquiring mind; facts have frequently been perverted; or distorted, by prejudice; anecdotes accumulated with little regard to selection or authenticity; and in general the history of this important period has been wanting in interest or information, either bare of domestic details, or without those luminous views of society, that spirit of inquiry, or that affluence of Literature and taste, so essential in the writer who should attempt to give a just and complete representation of the age of Elizabeth. In Miss Aikin we find an union of qualities rarely found to exist in the same mind; acute, yet diligent, patient research is combined with fancy, taste, and elegance. The dryness of historical detail is precluded; the flippancy or prolixity of domestic memoirs carefully avoided; the character of Elizabeth is naturally unfolded to the Reader . . . (44–45).

As Aikin asks her readers to do over and over again in Memoirs of the Court of Queen Elizabeth, we too can attempt to imagine how Aikin herself felt in reading such a review; the nature of the praise given to her history explains its enduring popularity with the public. With the commercial and critical success in her work as an historian, it is to be much regretted that her projected work on the social history of women in the eighteenth century was never completed (Schnorrenberg).

WPHP Records Referenced

Aikin, Lucy (person, author)

Barbauld, Anna Laetitia (person, author)

Epistles on Women, Exemplifying their Character and Condition in Various Ages and Nations. With miscellaneous poems (title, 1810)

Epistles on Women, Exemplifying their Character and Condition in Various Ages and Nations. With miscellaneous poems (title, 1810 Boston)

Hays, Mary (person, author)

"Taking Up the Cause: Mary Hays's Female Biography" (spotlight by Amanda Law)

"Mary Wollstonecraft and the Domestic Gothic Novel" (spotlight by Michelle Levy)

Memoirs of the Court of King Charles the First (title, 1833 first edition)

Memoirs of the Court of King Charles the First (title, 1833 second edition)

Memoirs of the Court of King Charles the First (title, 1833 Philadelphia)

Memoirs of the Court of King James the First (title, 1822 first edition)

Memoirs of the Court of King James the First (title, 1822 second edition)

Memoirs of the Court of King James the First (title, 1822 Boston)

Memoirs of the Court of Queen Elizabeth (title, 1818 first edition)

Memoirs of the Court of Queen Elizabeth (title, 1818 second edition)

Memoirs of the Court of Queen Elizabeth (title, 1819 third edition)

Memoirs of the Court of Queen Elizabeth (title, 1821 Boston)

Memoirs of the Court of Queen Elizabeth (title, 1823 fifth edition, revised and corrected)

Memoirs of the Court of Queen Elizabeth (title, 1826 sixth edition, revised and corrected)

Milton, John (person, author)

Poetry for Children. Consisting of Short Pieces, to be Committed to Memory (title)

Pope, Alexander (person, author)

Works Cited

Levy, Michelle. “‘The different genius of woman’: Lucy Aikin’s Historiography.” The Dissenting Mind: The Aikin Circle, 1740s -1860s, edited by Felicity James and Ian Inkster, Cambridge UP, 2011, pp. 156–82.

Levy, Michelle. "Lucy Aikin (1781-1864)." http://www.sfu.ca/~mnl/aikin/Site/Home.html.

Mellor, Anne K. “Telling Her Story: Lucy Aikin’s Epistles on Women (1810) and the Rewriting of Western History.” Women’s Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, vol. 39, no. 5, July 2010, pp. 430–50.

Mellor, Anne K, and Michelle Levy, eds. Lucy Aikin’s Epistles on Women and other Writing. Broadview, 2011.

Ready, Kathryn. “The Enlightenment Feminist Project of Lucy Aikin’s Epistles on Women (1810).” History of European Ideas vol. 31, no. 4, 2005, pp. 435–50.

“Memoirs of the Court of Elizabeth; by Lucy Aikin.” The Gentleman's Magazine: and historical chronicle, July 1818, pp. 44–45.

Schnorrenberg, Barbara Brandon. “Aikin, Lucy (1781–1864), historian.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford UP, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/231.

Tung, Shirley F. “Edenic Equality and the Rejection of “Right Divine” in Lucy Aikin’s Epistles on Women” (1810). European Romantic Review, vol. 31, no. 2, 2020, pp. 177–97.

Further Reading

Levy, Michelle. “The Radical Education of Evenings at Home.” Eighteenth-Century Fiction, vol. 19, no. 1-2, 2006, pp. 123–50.

McCarthy, William. Anna Letitia Barbauld: Voice of the enlightenment. John Hopkins UP, 2008.

McCarthy, William. The collected works of Anna Letitia Barbauld Anna Letitia Barbauld: The poems, revised, vol. 1. Oxford UP, 2019.