This post is part of Around the World with Six Women: A Travel Writing Spotlight Series, which will run through August 2021. Spotlights in this series focus on travel writing by women in the database.

Authored by: Julianna Wagar

Edited by: Michelle Levy and Kandice Sharren

Submitted on: 09/03/2021

Citation: Wagar, Julianna. “A Journey Through Scotland: Spence’s Letters from the North Highlands, During the Summer 1816.” The Women’s Print History Project, 3 September 2021, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/87.

Figure 1. Elizabeth Isabella Spence from La Belle Assemblée. Wikipedia.

Travelling through the North Highlands of Scotland and seeing the different beautiful landscapes, learning the histories of the land around you, and yearning for glimpses of Scottish folklore perfectly describes the experience of reading Letters from the North Highlands, During the Summer 1816 by Elizabeth Isabella Spence. Spence captures the essence of Scotland so eloquently, stopping to describe hidden gems of the North Highlands and explaining the histories behind each rock and tree she passes. Similar to Maria Graham's Journal of a Residence in Chile, Spence weaves historical narratives in with her travels, writing letters to her friend the novelist Jane Porter and paying special interest to the women of the North Highlands. Spence is late to the Scottish travel writing genre; however, she reworks this genre by focusing on the importance of personal connections as well as the historical narratives of Scotland. Spence, returning to her homeland after living in London for more than twenty years, engages readers as if they were journeying through the North Highlands with Spence herself as their tour guide.

Elizabeth Isabella Spence was born in Dunkeld, Perth in 1768. Her parents, Dr. James Spence and Elizabeth Spence, were avid readers which they passed down to their only child. Spence herself published three novels before she turned to travel writing, including Helen Sinclair (1799), The Nobility of the Heart (1804), and The Wedding Day (1807). Afterwards, she wrote three travel memoirs: Summer Excursions Through Parts of Oxfordshire, Gloucestershire, Warwickshire, Staffordshire, Herefordshire, Derbyshire, and South Wales (1809), Sketches of the Present Manners, Customs, and Scenery of Scotland, with Incidental Remarks on the Scottish Character (1811), and of course, Letters from the North Highlands, During the Summer 1816 (1817). Spence also wrote fiction tales, The Curate and his Daughter; A Cornish Tale (1813), The Spanish Guitar (1814), A Traveller’s Tale of the Last Century (1819), Old Stories (1822), How to be Rid of a Wife, and the Lily of Annandale: Tales (1823), and Dame Rebecca Berry; or, Court Scenes in the Reign of Charles the Second (1827).

When Spence began publishing Scottish travel writing, it was already an established genre. Although Sarah Murray wrote the first Scottish travel guidebook, A Companion and Useful Guide to the Beauties in the Western Highlands of Scotland, in 1799, those who followed after her were mainly men. Pam Perkins highlights how Scottish women travel writers were constantly oppressed by their male peers, who viewed travel writing as a man’s job (172). Perkins states that “Scotland in general and the Highlands in particular were coming to be seen as a site for the ‘cultivation of . . . masculinity’” (171). Men like John Stoddard thought that women were too weak or fragile to dig into the dirt and grime of Scotland and thus, their writing was not as detailed or effective as that of men (171). Many Scottish female writers were highly influenced by male writers, as Anne Grant, a popular Scottish poet and travel writer, was by James Macpherson’s poetry (Perkins 173). Grant focuses on the journey that Macpherson took and draws on his poetry: “Her writing becomes . . . the decorative accent on Macpherson’s ‘bold’ and ‘dark’ sublime . . . Grant more or less literally grounds her aesthetic vision in influential and authoritative masculine work” (173). Whereas Spence writes with women in mind within her Letters. Spence expresses excitement when viewing sites previously visited by women writers. For example, she references Grant’s former presence and its impact on her experience: “Perhaps the scenery was the more soothing to my imagination, from knowing the delight which it had afforded [Anne Grant]” (177). Spence even mentions Grant in her footnotes, calling Grant her “respected friend… the accomplished author of the ingenious and original ‘Letters from the Mountains'” (177).

While reading these Letters, one can feel a strong connection to Spence because of her intimate address to fellow author, Jane Porter. Jane Porter was well-known and admired for her novel, The Scottish Chiefs (1809). Perkins states that “[Porter] had a . . . great presence and influence in the Romantic-era literary world” (180). Spence was able to use Porter’s esteem to promote her Letters, but beyond that, Spence and Porter had a close friendship that was rekindled when Spence returned to Scotland. Spence and Porter were friends as children, thrust together through family ties but when Spence left for London, their friendship fizzled out (Orlando). Through these letters, Spence’s delight in her revived relationship with Porter mirrors the joy she feels in her returning to Scotland. Spence states "Yet, who is there, but at some period of life has not felt their heart glow with delight, when, after a lapse of time, the same objects are again presented, which formed a large portion of enjoyment. The same scene again meets the eye, the same hand is again extended, formerly pressed in youthful friendship" (52). Spence has such a prominent connection to Scotland and Porter, such that returning to one means returning to the other. We also see Spence’s great admiration of Porter in her dedication: "I shall be satisfied if I should have caught only one ray of that Genius which lives in every page of your admirable writings, for then I might hope to convey entertainment as well as information to the reader" (i). Spence’s relationship and connection to Porter fuels the intimate and personal narrative of these Letters.

Figure 2. Engraving of Jane Porter from 1846. Wikipedia.

Zoë Kinsley notes how Spence celebrates her womanhood and the independence that accompanies travel, writing of the liberation that she felt while travelling around London for her Summer Excursions (50). Letters from the North Highlands is not an explicitly political piece of travel writing, yet Spence weaves in commentary on women's rights and issues, and how women are treated differently in Scotland and London. Spence writes:

With less elegance of form, sweetness of voice, and persuasive grace of manner, [Scottish women] are more of nature and decided character in the Scottish than English females, in the same condition of life. This, I imagine, is owing to their being educated at home, except a year given to a boarding-school, where only accomplishments are taught. At home young ladies learn to think and feel, in a well-regulated and well-informed family, which alike cultivates the heart and understanding. (24)

Scottish women grow up surrounded by family, while many English women are sent to boarding schools where they acquire “a superficial education,” and thus develop “a superficial character, wholly engrossed with self” (25). Scottish women are taught to not only respect their family, but to learn from them.

Figure 3. Map of Scotland in 1814. Wikimedia Commons.

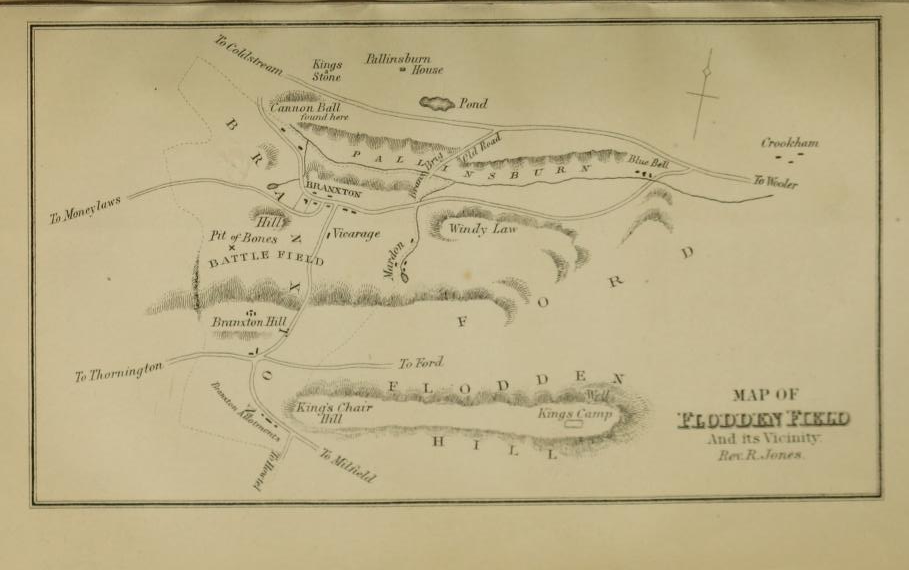

Spence began her journey in Trinity Lodge, near Edinburgh, leaving London in search of a historical and personal connection to Scotland. She begins her letters in June, stating “Having long felt an ardent desire to revisit my native country, I left London at a season when its gaieties present to multitudes the most powerful attraction” (1). Spence leaves London to experience the summer beauty of the North Highlands, which were scarcely visited by tourists. She specifically mentions Flodden Field, which was the site of the Battle of Flodden in 1513 between England and Scotland, which England won. Despite this loss, Spence writes of this site as an important landmark: "This dreary spot has been consecrated not merely by the blood of its warriors, but the tears of the Muses have been copiously poured forth, as a tribute to the unveiling valour of the slain; and the unutterable sorrow of the survivors'' (2). She discusses John Leyden, a Scottish poet, in reference to Flodden Field and his poem “Ode on Visiting Flodden.” She responds to his and other poetic accounts of the battle by saying, "it is impossible to pass with indifference a spot marked with such indelible traces in History, and consecrated to fame by successive poets” (3). Spence mentions places like Flodden Field throughout her letters, and instead of sweeping past their difficult histories, she highlights the loss and distress these sites arouse, describing the melancholic history of Scotland.

Figure 4. “Map of Flodden Field” by Reverend R. Jones. Wikimedia Commons.

She also references writing by famous authors like Robert Burns, Ann Radcliffe, and Shakespeare, as she visits different places that feature in or evoke their works. My favourite is her mention of Radcliffe's novel, The Mysteries of Udolpho. While she is in Stirling, she comes across the Castle of Gloom, about which she writes: "not all that Mrs. Radcliffe has described of the horrors of Udolpho, can exceed this place" (262). Spence read widely and was able to connect different landscapes to places that she has only read about, and her excitement about these places radiates off the page.

Figure 5. "Heron Hawking Below Stirling Castle" by Jan Wyck 1690, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1981.25.726

Figure 5. "Heron Hawking Below Stirling Castle" by Jan Wyck 1690, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1981.25.726

What makes Spence’s letters so special, is her admiration of Scotland. Despite having grown up in Scotland and growing accustomed to its landscapes and history, she is still able to capture the beauty around her. These descriptions take my breath away, as I imagine every inch of the North Highlands would. Spence writes as she travels along Loch Ness, specifically the Fall of Foyers: “Woods never appeared to me so verdant, or waters so clear, as those which met my view along this road, as glimpses of the translucent, or rushing mountain-streams, casually appeared through shades of tremulous birch” (166). As she travels from more central places like Edinburgh and Stirling to the less-populated and vast landscapes of Aberdeen and Inverness, her writing moves from the certainty of the familiar landscapes to astonishment. Her description of summer nights in Ross are especially affecting:

You can imagine nothing half so beautiful as the summer evenings in Scotland. The dark curtain of night is scarcely spread in this northern hemisphere... The firmament retains a glow of light, often brilliantly heightened by the aurora borealis, here called, the merry dancers, which has a grand effect; and, when the softer shades of evening prevail, and throw into partial gloom the sleeping landscape, it is even at midnight, during the months of May, June, and July, only like our evening at twilight, when every object is indistinctly visible. The grandeur of the mountains, the pellucid tranquility of the rivers, and the deep gloom of the dark fir woods, altogether form a scene no person who has not beheld it, can picture. (153–54)

Figure 6. "View of the City of Edinburgh" by Alexander Nasmyth, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1974.3.21

As she journeys along the North Highlands, she is drawn to the folklore of the locals. Spence shares a superstition of Inverness, on the Hill of the Fairies, Tom-ma-heurich. She writes "the signification of the Gaelic, Tom-na-heurich, is, the Hill of the Fairies, or under-ground inhabitants, who are supposed to visit it at certain times, to hold their revels. It is superstitiously believed to this day, that various cures are effect upon the sick" (125). According to this superstition, if one spends the night under the hill, they are cured of their ailments. Weaving the lore of Scotland throughout her letters not only provides an interesting insight into the lives of Scottish people in the eighteenth century, but it shows us the whimsical storytelling in those regions that has prevailed for centuries.

Letters from the North Highlands, During the Summer 1816 is an alluring tale of history, friendship, folklore, and the landscapes of Scotland. Spence partners her eloquent writing with the stunning backdrop of Scotland and entices readers to learn about the history within each landmark and area of the North Highlands. Following her journey from Trinity Lodge to St. Andrew's Square, she tackles every inch of the North Highlands, bringing historical and personal narratives of the townspeople and architecture.

WPHP Records Referenced

Spence, Elizabeth Isabella (person, author)

Letters from the North Highlands, During the Summer 1816 (title)

Graham, Maria (person, author)

Journal of a Residence in Chile (title)

Porter, Jane (person, author)

Helen Sinclair (title)

The Nobility of the Heart (title)

The Wedding Day (title)

The Curate and his Daughter; A Cornish Tale (title)

The Spanish Guitar. A Tale; for the use of young persons (title)

A Traveller’s Tale of the Last Century (title)

Old Stories (title)

How to be Rid of a Wife, and the Lily of Annandale: Tales (title)

Dame Rebecca Berry; or, Court Scenes in the Reign of Charles the Second (title)

Sarah Murray (author)

A Companion and Useful Guide to the Beauties in the Western Highlands of Scotland (title)

Grant, Anne (author)

Letters from the Mountains (title)

The Scottish Chiefs (title)

Radcliffe, Ann (person, author)

The Mysteries of Udolpho (title)

Works Cited

Brown, Susan, Patricia Clements, and Isobel Grundy, eds. “Elizabeth Isabella Spence.” Orlando: Women's Writing in the British Isles from the Beginnings to the Present, Cambridge UP Online, 2006.

Kinsley, Zoë. “'Coming Before the Public in the Character ... of a Tourist': Travellers' Textual Choices.” Women Writing the Home Tour, 1682-1812, Routledge, 2016, pp. 45–73.

Perkins, Pam. “‘News from Scotland’: Female Networks in the Travel Narratives of Elizabeth Isabella Spence.” Women's Writing, vol. 24, no. 2, 2016, pp. 170–184.

Spence, Elizabeth Isabella. Letters from the North Highlands, During the Summer 1816. Longman, 1817.