This post is part of our Black Women's and Abolitionist Print History Spotlight Series, which will run between 19 June and 31 July 2020. Spotlights in this series focus on our work to find Black women who were active participants in the book trades during our period, to acknowledge the ways in which white female abolitionists exploited print’s powerful potential for eliminating slavery, and to revisit the lives and books published by well-known Black female authors.

Authored by: Amanda Law

Edited by: Michelle Levy and Kandice Sharren

Submitted on: 07/10/2020

Citation: Law, Amanda. "The Transatlantic Publication of Phillis Wheatley's Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral." The Women's Print History Project, 10 July 2020, www.womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/25.

Figure 1. Portrait of Phillis Wheatley, attributed by some scholars to Scipio Moorhead, British Library, 992.a.34.

Phillis Wheatley* is perhaps best known as the first African-American to publish a book of poems. Born in West Africa c. 1753, Wheatley was sold into slavery in 1761 and brought to Boston, Massachusetts where she was purchased by the merchant John Wheatley for his wife, Susanna, who sought to “secure herself a faithful domestic in her old age” (Wheatley et al. 11). Phillis Wheatley learned to read and write under the instruction of Susanna and her daughter Mary. She published her first poem in 1767 (“On Messrs Hussey and Coffin”) in the December 21st issue of the Newport, Rhode Island, Mercury.

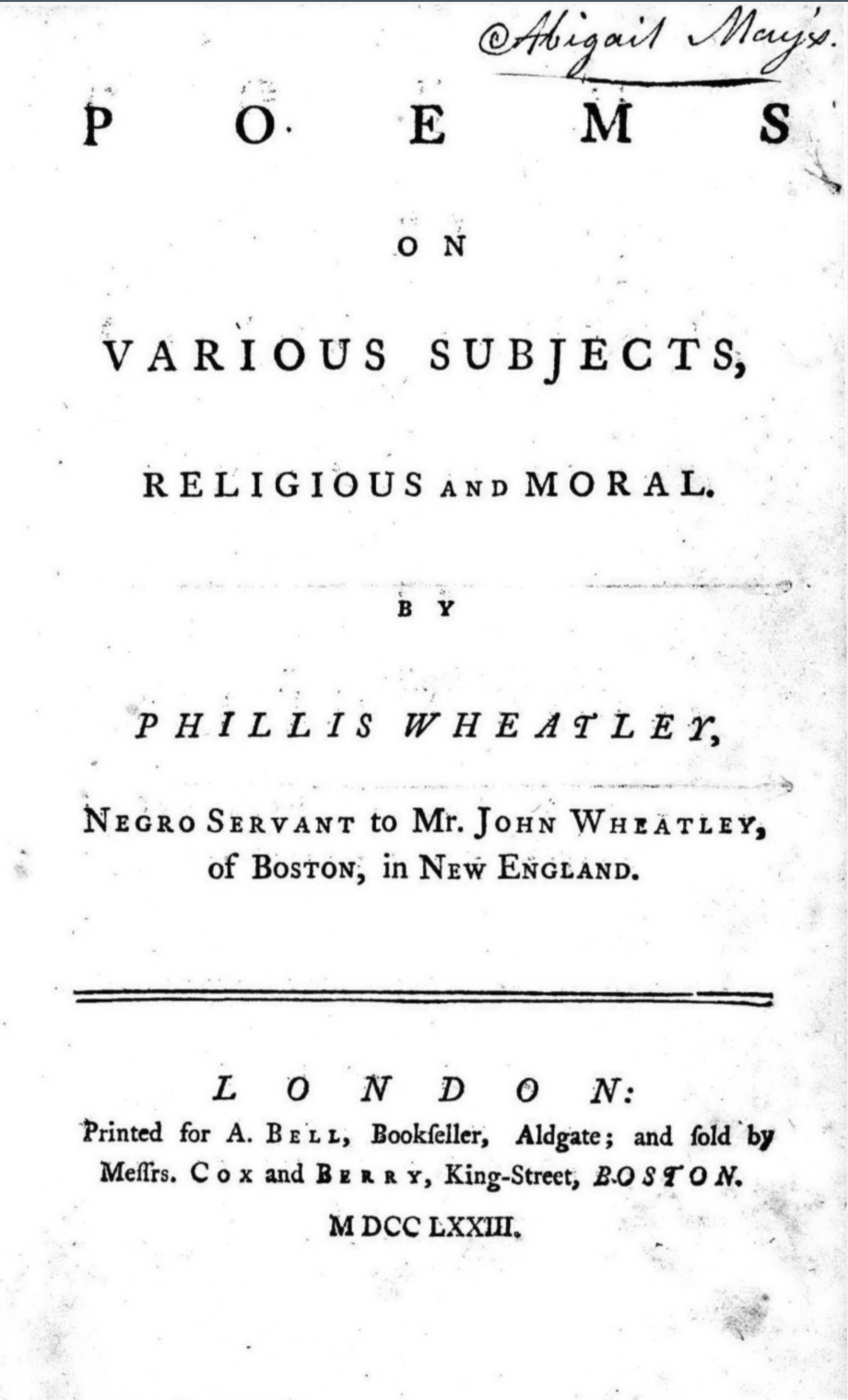

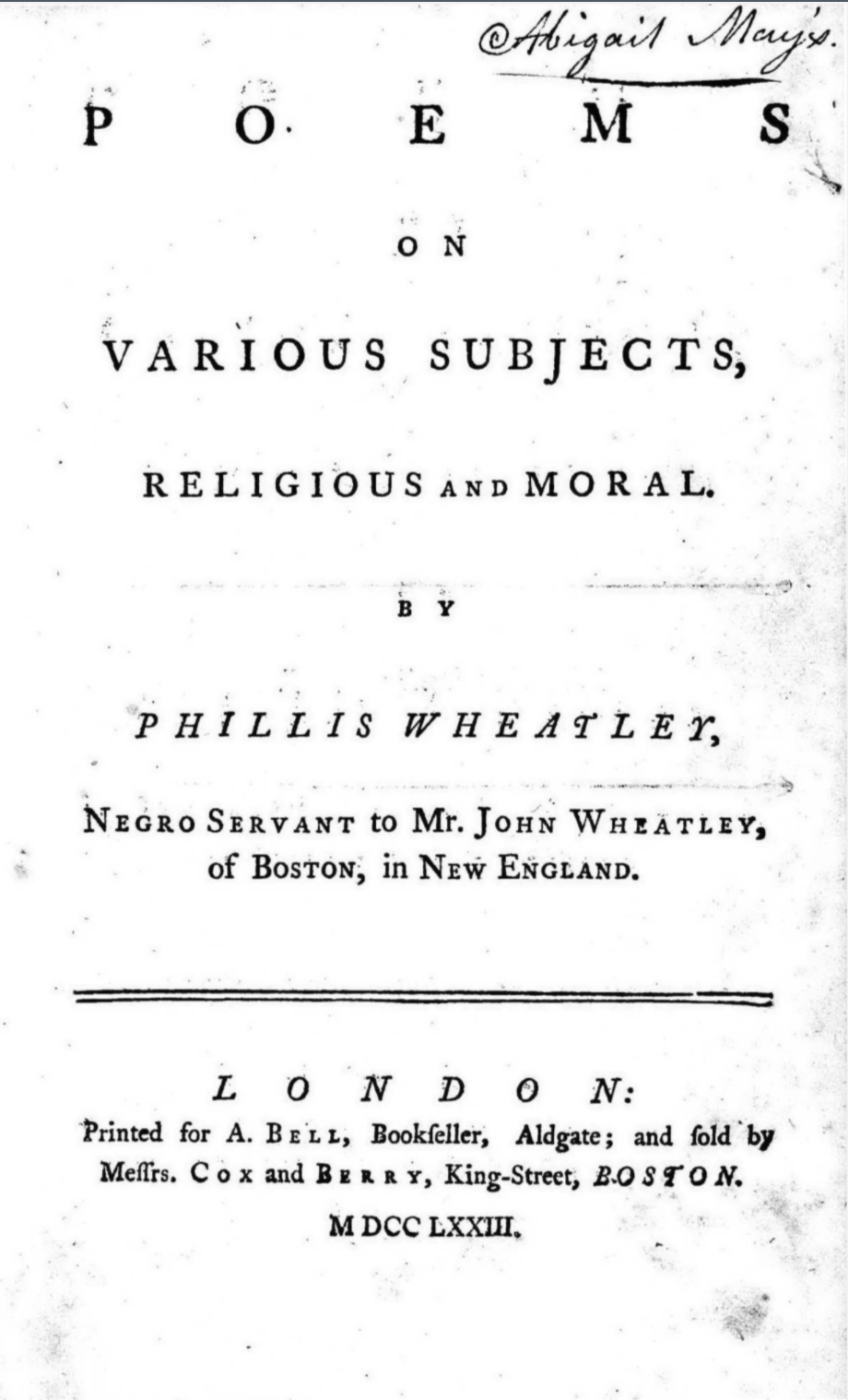

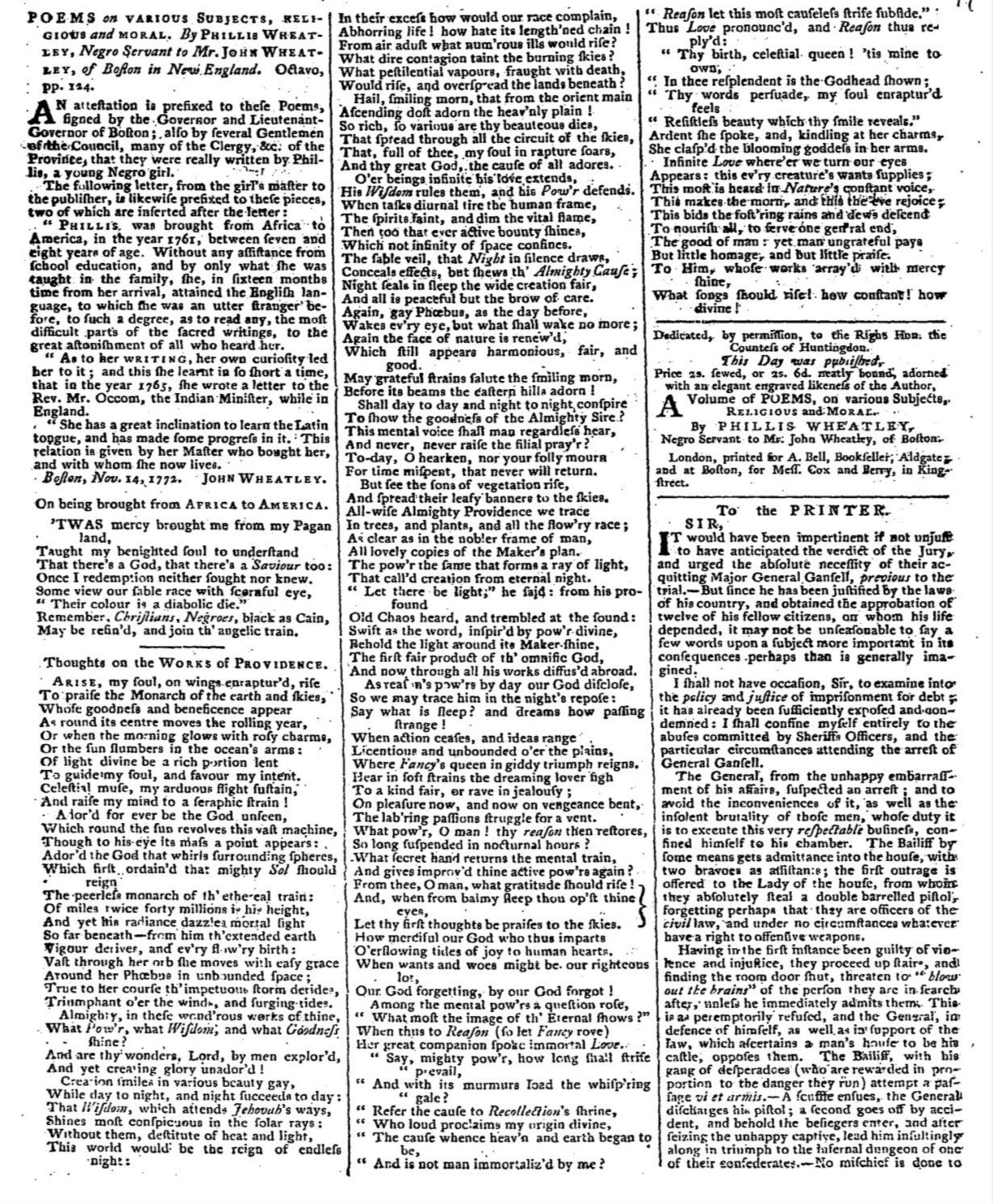

Figure 2. 1773 Edition with all prefatory material. NCCO.

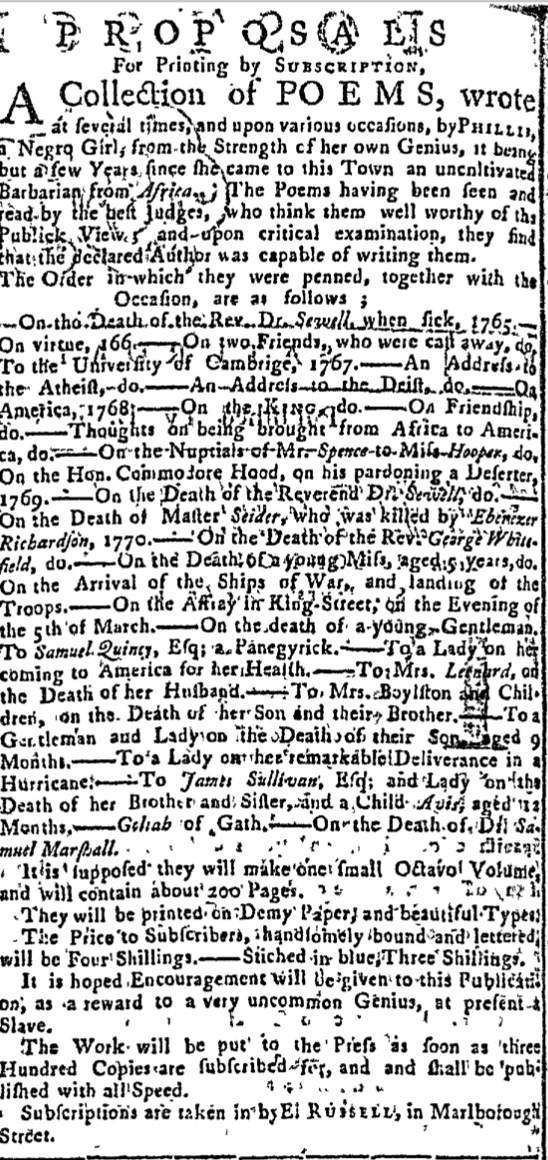

When Wheatley published Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral in London in 1773, she had to navigate a complicated publication process that required her to traverse the Atlantic to see her work come to fruition. Wheatley originally intended to publish her collection in Boston, and in 1772, with the help of Susanna, she advertised a collection of twenty-eight poems “by Phillis, a Negro Girl, from the strength of her own Genius” in the Boston Censor, a short-lived periodical that only ran from 1771-1772. They intended for the volume to be an octavo of about two hundred pages and priced the “handsomely bound and lettered” edition at four shillings while the edition “stitched in blue” would cost three.

Figure 3. 1772 Boston Censor advertisement, The Open Anthology of Literatures in English.

Wheatley and Ezekiel Russell, the owner of the Boston Censor, planned to publish her book by subscription, intending to begin printing copies once 300 subscribers committed to purchasing the book. The advertisement ran three times that year, in February, March, and April (Shields 193), but it seems they were unable to amass enough subscribers. Robinson suggests that the lack of enthusiasm for Wheatley’s collection was due to “early Boston racist refusal” (187) to believe she had authored the poems, gesturing to a letter written by Boston merchant John Andrews, who had subscribed for the book, to his brother William Barrell on 24 February 1773.

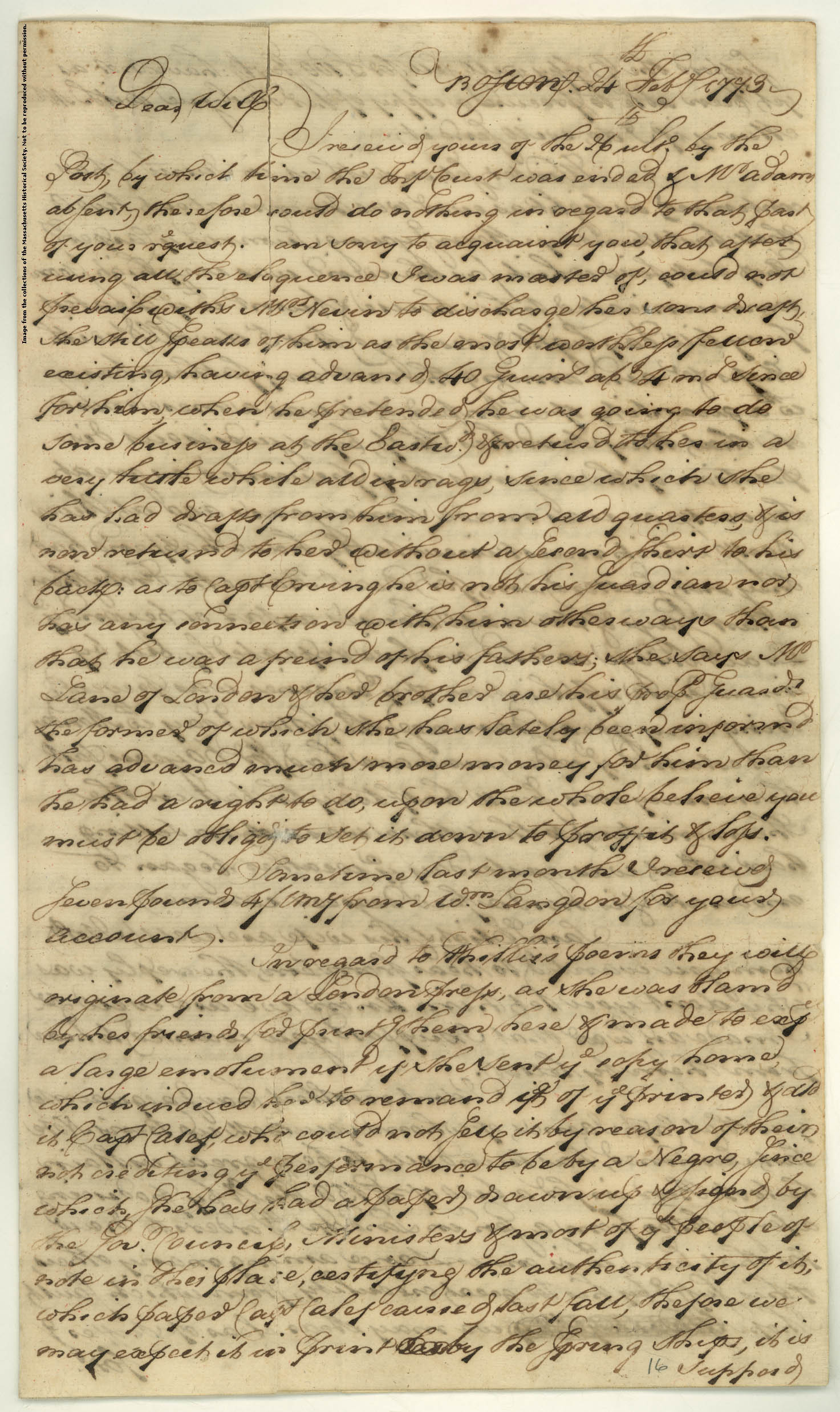

Figure 4. Letter from John Andrews to William Barrell, 24 February 1773. Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

The Massachusetts Historical Society transcribes the section referring to Wheatley’s collection as follows:

In regard to Phillis's poems they will originate from a London press, as she was blamd by her friends for printg them here & made to expd a large emolument if she sent ye copy home, which induced her to remand yt of ye printer & dld [delivered] it Capt Calef, who could not sell it by reason of their not crediting ye performance to be by a Negro, since which, she has had a paper drawn up & signd by the Govr. Council, Ministers & most of ye people of note in this place, certifying the authenticity of it; which paper Capt Calef carried last fall, thefore [therefore] we may expect it in print las by the spring ships, it is supposed the Coppy will sell for £ 100 sterlg: have not as yet been able to procure a coppy of her dialogue with Mr Murry, if I do, will send it.

Captain Robert Calef worked for the Wheatley family and, as implied by this excerpt, presented Wheatley’s manuscript to different prospective publishers and financiers when her call for subscribers in the Boston Censor yielded less than promising results. As Andrews indicates in his letter, people held suspicions about the veracity of Wheatley’s authorship.

Unable to amass her desired audience in Boston, Wheatley turned to London at the prompting of Susanna, who had many contacts in England. In Boston in 1770, Wheatley published, as a broadside, a widely celebrated eulogy on the English evangelist George Whitefield (An Elegiac Poem, on the Death of that Celebrated Divine, and Eminent Servant of Jesus Christ, the Late Reverend, and Pious George Whitefield), from which she had garnered most of her fame. She mailed a manuscript of this poem to Selina Hastings, the Countess of Huntingdon on 2 October 1770. Whitefield had been the Countess’s personal and much respected chaplain and Susanna knew the Countess through their dissenting evangelical Methodist organization. Wheatley had maintained this connection to the Countess since 1770 and, when she turned to her in 1772 after her disappointment in Boston, the Countess agreed to finance the publication of Wheatley’s poems by London bookseller Archibald Bell. In an effort to garner more attention for Wheatley’s collection, the Countess allowed the book to be dedicated to her, which is advertised in the title of the 1802 American edition. In addition, the Countess interrupted the production of the book until a portrait of Wheatley could be commissioned for the preface (see the top of the page).

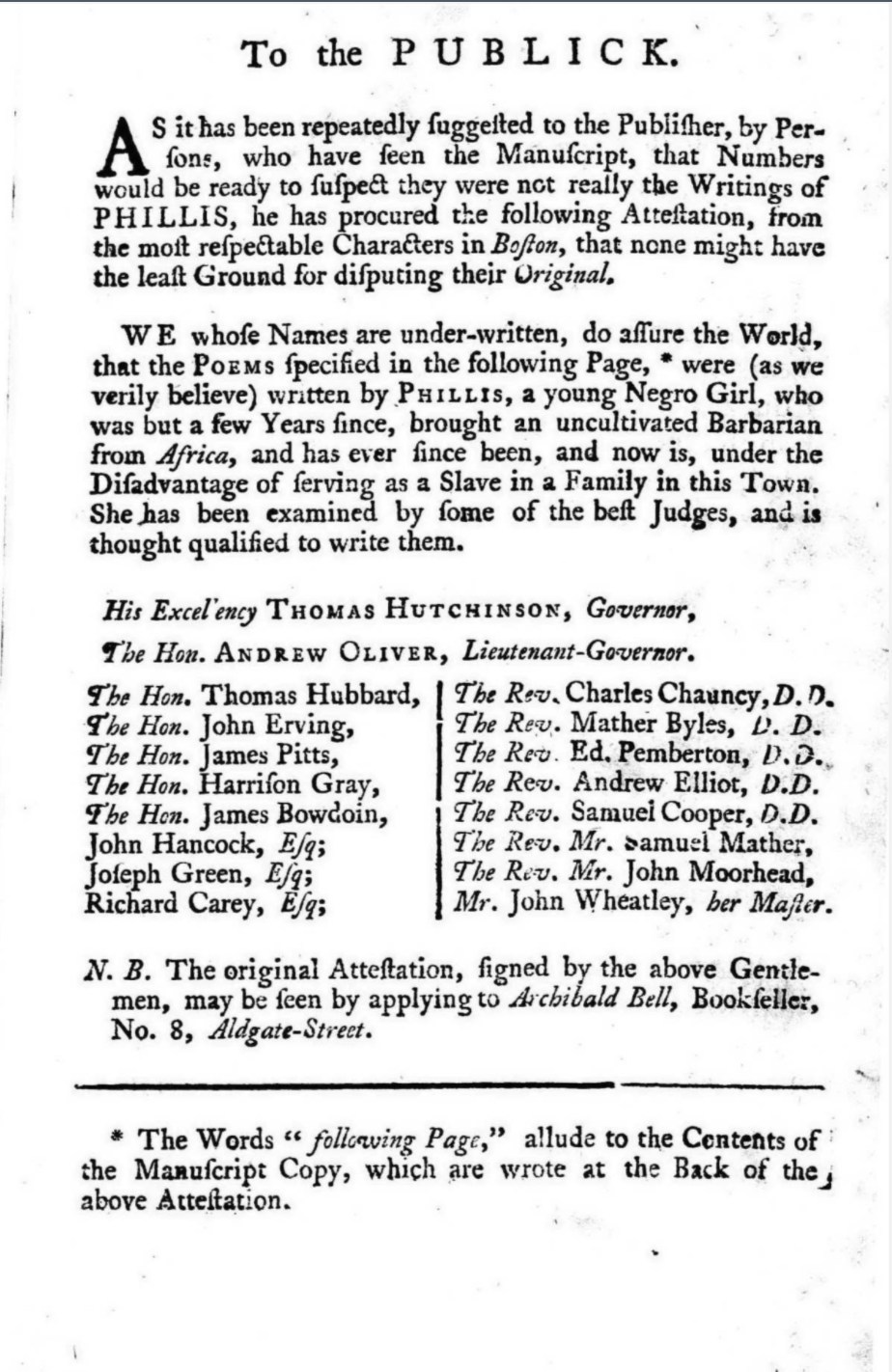

Although the abolition movement was much stronger in London than Boston in the 1770s, distrust of Wheatley’s poetic ability due to her race still persisted. When Captain Calef traveled to London on behalf of the Wheatleys to meet with the Countess and Bell, he brought the attestation which can be found in the preface of Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. This is a document signed by prominent figures in Boston including reverend Charles Chauncey, John Hancock, Thomas Hutchison, the governor of Massachusetts, and his Lieutenant Governor, Andrew Oliver, verifying that they had examined Wheatley in court and deemed she was capable of the work she claimed as her own. Similar to The History of Mary Prince (read Sara Penn’s spotlight on this title here), which included supplementary material that “sought to establish the veracity of Prince’s account and her credibility” (Penn), Wheatley’s book required this material to dispel racist disbelief of her abilities.

Figure 5. Attestation from 1773 edition with all prefatory material. NCCO.

Wheatley arrived in London from Boston on June 17, 1773 accompanied by Nathaniel Wheatley, John Wheatley’s son, to oversee the publication of her book. During her time in London, she was kept busy revising the poems for her book and visiting English nobility and dignitaries. She was hosted by Granville Sharp and met with Ignatius Sancho, who dubbed her ‘Genius in bondage’ (British Library) (read Kate Moffatt’s spotlight on his wife, bookseller Ann Sancho, here!). Wheatley’s trip was cut short as Susanna fell ill, forcing Wheatley to return to Boston before she could meet the Countess of Huntingdon in person, before her scheduled audience with King George III, and before her book was even published.

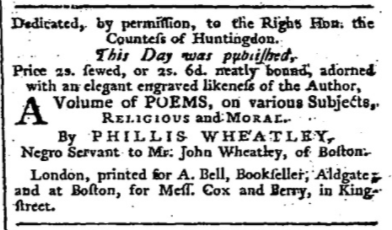

On 16 September 1773, the collection was finally ready, and the London Chronicle announced its appearance in a full-page spread:

Figure 6. 16-18 September 1773 London Chronicle advertisement for Wheatley’s collection, sold by Archibald Bell in London and Cox and Berry in Boston, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection.

Mukhtar Ali Isani argues that the prefatory material that accompanied the text diverted attention away from Wheatley’s poems themselves towards her race and enslavement. While this may have detracted from her work, this attention may have also contributed to her emancipation soon after the publication of her collection. London reviews of the book gestured to the hypocrisy of the attestation verifying her abilities even while she was still enslaved. A review in the September 1773 issue of Gentleman’s Magazine condemned the fact that so many prominent figures signed the attestation and yet “[y]outh, innocence, and piety, united with genius, have not yet been able to restore [Wheatley] to the condition and character with which she was invested by the Great Author of her being” (qtd. in Isani 146). Perhaps as a result of this sort of criticism, the Wheatleys freed Phillis Wheatley in November 1773.

Robinson notes that there was a first London edition of Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral that did not contain all of the prefatory material because Bell withheld this material to release it in newspapers as promotional content (196). He also states that “English concern” (199) with Wheatley would continue well beyond her death in Boston in 1784, even leading to a “second edition” in 1787, retitled Poems on Comic, Serious, and Moral Subjects and published by John French. Our database contains several American editions with the original title published after 1784 (1786, 1787, 1789, 1793, 1801, 1802, 1804, 1816), but we are still searching for further London editions and any other American editions we may be missing. If you have any information or find an edition we do not have, please contact us.

*Note: As of February 15, 2024, we've updated Phillis Wheatley Peters's Person record to include her married surname to reflect current scholarship.

WPHP Records Referenced

Wheatley, Phillis (person, author)

Wheatley, John (person, editor)

Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (title, 1773 edition with all prefatory material)

Russell, Ezekiel (firm, publisher, and bookseller)

Archibald Bell (firm, publisher, and bookseller)

Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (title, 1802 American edition)

The History of Mary Prince (title)

"The First Slave Narrative by a Woman: The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave" (title spotlight by Sara Penn)

Sancho, Ignatius (person, author)

"A Search for Firm Evidence: Uncovering Ann Sancho, Bookseller" (spotlight by Kate Moffatt)

Messrs. Cox and Berry (firm, bookseller)

Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (title, first London edition)

Poems on Comic, Serious, and Moral Subjects (title)

John French (firm, publisher)

Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (title, 1786 American edition)

Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (title, 1787 American edition)

Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (title, 1789 American edition)

Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (title, 1793 American edition)

Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (title, 1801 American edition)

Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (title, 1804 American edition)

Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (title, 1816 American edition)

Works Cited

Isani, Mukhtar Ali. “The British Reception of Wheatley's Poems on Various Subjects.” The Journal of Negro History, vol. 66, no. 2, 1981, pp. 144–149.

Penn, Sara. “The First Slave Narrative by a Woman: The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave.” The Women's Print History Project, 3 July 2020, womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/22.

“Phillis Wheatley, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral.” The British Library (blog), 8 Oct. 2015, www.bl.uk/collection-items/phillis-wheatleys-poems.

Robinson, William H. “PHILLIS WHEATLEY IN LONDON.” CLA Journal, vol. 21, no. 2, 1977, pp. 187–201.

Shields, John C. Phillis Wheatley and the Romantics. U of Tennessee P, 2010.

Wheatley, Phillis, et al. Memoir and poems of Phillis Wheatley : a native African and a slave; also, Poems by a slave. 3rd ed., Published by Isaac Knapp, 1838. Sabin Americana: History of the Americas, 1500-1926, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CY0112087195/SABN?u=sfu_z39&sid=bookmark-SABN&xid=17c67964&pg=1. Accessed 5 July 2020.

Further Reading

Cataldo, Ashley. "The Manuscript Poems of Phillis Wheatley at AAS." Past is Present, The American Antiquarian Society, 21 July 2020, https://pastispresent.org/2020/good-sources/the-manuscript-poems-of-phillis-wheatley-at-aas/.

Isani, Mukhtar Ali. “The Contemporaneous Reception of Phillis Wheatley: Newspaper and Magazine Notices During the Years of Fame, 1765-1774.” The Journal of Negro History, vol. 85, no. 4, 2000, pp. 260–273.

Nott, Walt. “From ‘Uncultivated Barbarian’ to ‘Poetical Genius’: The Public Presence of Phillis Wheatley.” MELUS, vol. 18, no. 3, 1993, pp. 21–32.

Robinson, William Henry. Black New England Letters: the Uses of Writing in Black New England. Trustees of the Public Library of the City of Boston, 1977.

Wilcox, Kirstin. “The Body into Print: Marketing Phillis Wheatley.” American Literature, vol. 71, no. 1, 1999, pp. 1–29.