This post is part of our Black Women's and Abolitionist Print History Spotlight Series, which will run between 19 June and 31 July 2020. Spotlights in this series focus on our work to find Black women who were active participants in the book trades during our period, to acknowledge the ways in which white female abolitionists exploited print’s powerful potential for eliminating slavery, and to revisit the lives and books published by well-known Black female authors.

Authored by: Sara Penn

Edited by: Michelle Levy and Kandice Sharren

Submitted on: 07/03/2020

Citation: Penn, Sara. "The First Slave Narrative by a Woman: The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave." The Women's Print History Project, 3 July 2020, www.womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/22.

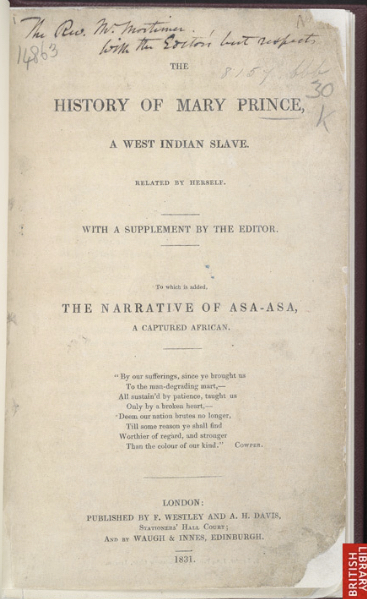

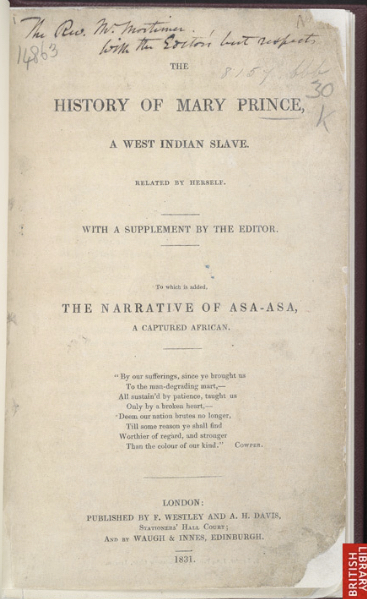

Figure 1. First edition. British Library, 8157.bbb.30.

Mary Prince was born into slavery c. 1788 in Bermuda and is best known for her book, The History of Mary Prince, a West Indian Slave. Related by Herself. With a Supplement by the Editor. To which is added, The Narrative of Asa-Asa, A Captured African. Prince played a vital role in Britain’s abolitionist movement as the first Black woman whose narrative of her enslavement was recorded.

In creating data for the title records of Prince’s History interpretative decisions were necessary. According to James Olney, slave narratives should not necessarily be classified as “autobiography” or even “literature” due to the cumulative objective reality of the African experience, or “sameness,” that they record (46). The purpose of these narratives are political, as they were used to document the horrors of slavery and convince the public (the English public, in Prince’s case) to abolish colonial slavery. For these reasons, Prince’s testimony is included in our database as Political Writing to prioritize its chief aim of bringing about the immediate and total abolition of slavery. This designation of genres is one of the most interpretative acts in the process of data creation—many of the works in our database satisfy multiple categories (indeed, the History could be classified as a Memoir, History, or Legal) and it is up to us to decide which of these categories best depict the work.

Prince’s narrative also raises issues of collaboration and how to assess and define contributions to a title. The title page to the History is described as having been “related by herself.” What this means is that the narrative was told to Thomas Pringle, a white abolitionist and secretary of the Anti-Slavery Society, and Susanna Strickland (who in 1832 emigrated to Canada and is now known as Susanna Moodie). Pringle included supplementary materials such as testimonies, footnotes, and an appendix, all of which sought to establish the veracity of Prince’s account and her credibility as a witness to slavery’s crimes. As Sara Salih points out, the History is “by no means self-authenticating” and is “best described as a concatenation of mutually validating and interlinked documents” rather than a single-authored narrative (132).

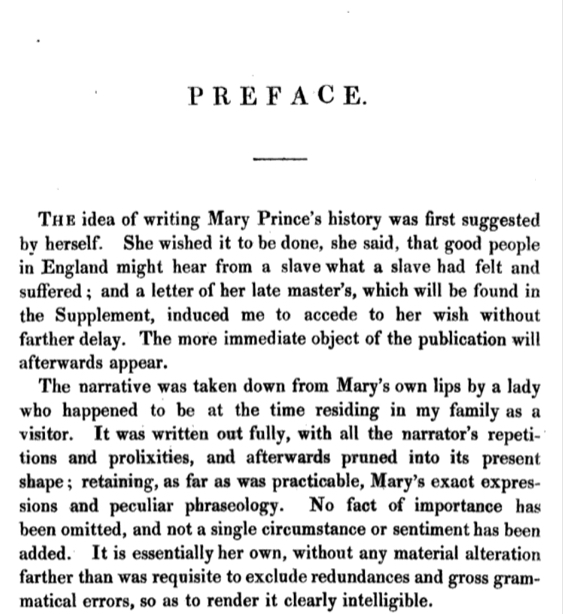

Pringle and Strickland refuted any claim that they may have altered the narrative, admitting only to changes to “exclude redundancies and gross grammatical errors” (ii; Black 702). Indeed, Margôt Maddison-MacFadyen claims that most proper pronouns are written incorrectly because Strickland and Pringle “were unfamiliar with Bermudian and Antiguan place names and surnames” (Introduction). In the preface, Pringle makes sure to note that the narrative is written in Prince’s own words:

Figure 2. First edition. Google Books.

By asserting that Strickland had omitted “no fact of importance” and that “not a single circumstance or sentiment has been added,” Pringle sought to establish Prince’s account as first-hand testimony of the evils of slavery. Prince also rarely reports any event or action she has not witnessed herself. Although, as we will see, aspects of Prince’s narrative were contested by proponents of slavery and her enslaver, John Wood, there is no evidence to challenge Pringle’s claim that the narrative was “taken down” by Strickland as described. In this way, although Prince, it seems, never put pen to paper, we can assert her as author of the title. Pringle, by including various paratexts, is the editor of the title, as, to use our definition from this contributor role, he “selected, revised, and arranged the work for print.” Strickland was also an editor, as she revised, however sparingly, the narrative she took down from Prince. We do not have amanuensis as a category in our Contributor Roles, but we indicate this in our notes field.

Recovering basic biographical data about enslaved persons is another challenge that we, as researchers, seek to navigate. Prince’s Person Record does not reveal the date or place of death, and the date of birth is an estimate. This unidentifiable data is an aspect of slavery itself, where the process of dehumanization meant that birthdays were neither known or celebrated by enslaved peoples. Due to her untraceable record, most of what we know about Prince derives from her History. Born in Brackish Pond, Bermuda, Prince was born the property of planter Charles Myners. After his death, when Prince was an infant, she and her family were sold to Captain Williams. After the death of his wife, when Prince was twelve, she was sent with her siblings to the slave market, where she was sold for £38 to Captain and Mrs. Ingham (they are referred to as Captain and Mrs. I in the History, an attempt by her editors to protect Prince—and them—from libel suits). The Inghams took Prince to Spanish Point, Bermuda, and abused her mentally and physically for five years. Prince was then sent to Turks Island to work for her new owner, Mr. D—, in the saltwater ponds. This was excruciating work as it required the workers to stand working for up to seventeen hours in shallow saltwater. Mr. D— returned to Bermuda, in 1801, with Prince, where she completed domestic chores and worked in the fields. After complaining to Mr. D— about his indecent treatment, she was hired out to work at Cedar Hills—“two dollars and a quarter a week, which is twenty pence a day” (14)—all of which was paid to her planter. Seeking to remove herself from Mr. D—‘s sexual abuse, she had herself bought by Mr. Wood, her fifth enslaver, who was travelling to Antigua.

Once in Antigua, she became seriously impaired by rheumatism, possibly brought about by her work in the salt ponds. Nursed back to health by neighbours and enslaved friends, she was determined to buy her emancipation by selling coffee and yams. At the Moravian church, which welcomed Prince, teaching her to read and admitting her to holy communion. She met Daniel James, a previously enslaved person who had purchased his freedom, at church, and they were married in the Moravian chapel in Antigua in 1826. Mr. D— was enraged by her marriage, as slaves were not free to marry. Prince states that she ”had not much happiness in my marriage, owing to my being a slave” (18). In 1828, Wood was travelling to England to place his children in school; Prince was willing to travel with him to London as she believed it would cure her rheumatism, and also because she and her husband thought it might be the means of her obtaining her freedom.

As a result of the legal decision in Somerset v. Stewart, in 1772, slavery was deemed illegal in Britain. On English soil, therefore, Prince was liberated but could not support herself due to the fact that the only work she could find involved washing, which caused severe suffering given her rheumatism. She continued to work to purchase her freedom, which would allow her to return to her husband a free woman. She found employment as a domestic servant to Thomas Pringle in 1829, and in that same year she petitioned in Parliament for her human right to freedom, being the first woman to do so. In this same year, a bill was proposed that any enslaved person brought to England from the West Indies must be freed. Prince and the bill were both declined. As a result, she could not return to Antigua, and be reunited with her husband, without being re-enslaved.

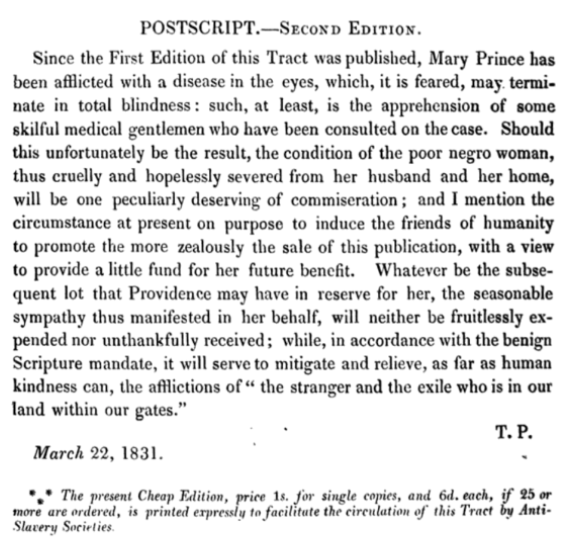

Figure 3. Prince lived with Thomas and Margaret Pringle in Claremont Square, London. Margôt Maddison-MacFadyen, https://www.maryprince.org/.

In 1831, Pringle offered to publish her record of enslavement. The narrative, however, was not without controversy. James MacQueen, pro-slavery editor of Blackwood’s Magazine (1817-1980), declared that it was fraudulent. Pringle responded by successfully suing the magazine’s publisher, Thomas Cadell, and received £5 in damages. Wood additionally sued Pringle for defamation of character in the History, and Pringle responded with a countersuit. Records indicate that Prince testified at both cases and lost. Wood was compensated £25. News of the case had circulated and only increased the popularity of the book to its British readership, resulting in three editions within its first year of publication (although a preface to the second edition was reprinted in the third, not a single copy of the second edition has been found, possibly, this is because it was a very inexpensive edition; it was advertised as a “Cheap Edition, price 1s. for single copies, and 6d. each, if 25 or more are ordered”). After these trials, Prince’s history is unknown: there was no trace of her after she testified in the two libel trials—she may have stayed in London or returned to her husband in Bermuda.

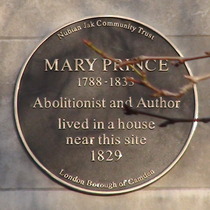

Figures 4 and 5. Postscript and plaque, from the London Senate House, dedicated a plaque to Prince on Malet St. London Remembers.

In 1833, two years after the first three editions were published, Great Britain’s Slavery Abolition Act was passed by parliament, and approximately 800 000 enslaved peoples in British colonies were liberated. In 2012, Bermuda recognized Prince as a National Hero, for which a holiday is observed in her honour on June 18th. In 2018, Google celebrated Prince’s 230th birthday with a Doodle.

Figure 6. Google Doogle.

We are grateful to P. Gabrielle Foreman at the University of Delaware for her helpful document outlining the semantics of discourse about slavery.

WPHP Records Referenced

Prince, Mary (person, author)

Political Writing (genre)

Genre (field)

Memoir (genre)

History (genre)

Legal (genre)

Pringle, Thomas (person, editor)

Strickland, Susanna (person, editor)

Author (contributor role)

Editor (contributor role)

Contributor Roles (field)

Person Record (field)

Thomas Cadell (firm, publisher)

The History of Mary Prince (title, third edition)

The History of Mary Prince (title, second edition)

Works Cited

Black, Joseph, et al., eds. “Mary Prince.” The Broadview Anthology of British Literature: The Age of Romanticism, Volume Four. 3rd ed. Broadview, 2018, pp. 702–23.

Maddison-MacFadyen, Margôt. "Introduction." https://www.maryprince.org/

Olney, James. “‘I was Born’: Slave Narratives, Their Status as Autobiography and as Literature.” Callaloo, no. 20, Winter, 1984, pp. 46–73.

Prince, Mary. “The History of Mary Prince, a West Indian Slave. Related by Herself. With a Supplement by the Editor. To Which Is Added, the Narrative of Asa-Asa, a Captured African.” Documenting the South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 29 July 2000, https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/prince/prince.html.

Salih, Sara. “The History of Mary Prince, the Black Subject, and the Black Canon.” Discourses of Slavery and Abolition: Britain and its Colonies, 1760-1838, edited by Brycchan, Carey, Markman Ellis, and Sara Salih, Palgrave, 2004, pp. 123–38.

Further Reading

Banner, Rachel. “Surface and Stasis: Re-Reading Slave Narrative via The History of Mary Prince.” Callaloo, vol. 36, no. 2, 2013, pp. 298–311.

Foreman, P. Gabrielle, et al. “Writing about Slavery/Teaching About Slavery: This Might Help” community-sourced document, 2018, https://docs.google.com/document/d/1A4TEdDgYslX-hlKezLodMIM71My3KTN0zxRv0IQTOQs/edit.

Maddison-MacFadyen, Margôt. "Mary Prince and Grand Turk." Bermuda Journal of Archaeology and Maritime History, vol. 19, 2009, pp. 102–23.

Maddison-MacFadyen, Margôt. "Mary Prince: Black Rebel, Abolitionist, Storyteller." Critical Insights: The Slave Narrative, edited by K. Drake, Salem, 2014, pp. 1–30.

Maddison-MacFadyen, Margôt. "Mary Prince, Grand Turk and Antigua." Slavery & Abolition: A Journal of Slave and Post-Slave Studies, no. 34, vol. 4, 2013, pp. 653–62.

Maddison-MacFadyen, Margôt. "Piecing Together the Puzzle: The Antiguan years of Mary Prince." Times of the Islands, 94, 2011, pp. 44–48.

Maddison-MacFadyen, Margôt. "Toiling in the Salt Ponds: The Grand Turk years of Mary Prince." Times of the Islands, 84, 2008, pp. 77–88.