This post is part of our Spooky Spotlight Series, which will run through October 2020. Spotlights in this series focus on Gothic titles, authors, and firms in the database.

Authored by: Kate Moffatt

Edited by: Michelle Levy and Kandice Sharren

Submitted by: 10/16/2020

Citation: Moffatt, Kate. "A Gothic Ménage: Guénard, The Three Monks!!!, and Translation." The Women's Print History Project, 16 October 2020, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/40.

Figure 1. Title page of H.J. Sarrett's translation of Elisabeth Guénard's The Three Monks!!! (1803). NCCO.

In 1803, French writer Elisabeth Guénard’s Les Trois Moines was published in Paris under the pseudonym Monsieur de Favrolles. Following the lives of three illegitimately-born young monks—Anselmo, Dominico, and Silvino—the two-volume gothic novel traipses delightedly through the towns and mountains of Italy, featuring no less than three abbeys, one set of subterraneous caverns, one successful kidnapping, one failed kidnapping, an assassination, a country-wide and nobility-led crime ring, a mountain hermit, many mistresses, and our three incredibly ill-behaved monks.

In the same year, an English translation of Les Trois Moines by H.J. Sarrett was published by Benjamin Crosby and Co. in London under the title The Three Monks!!!. It was Sarrett’s addition of the three exclamation marks to the title that initially drew the largely forgotten novelist’s work to the attention of the WPHP team, and it was Sarrett’s translation and publication in London that resulted in the inclusion of Guénard’s The Three Monks!!! in the WPHP. At the time of writing this spotlight, we only include works published in Great Britain and Ireland, and we are beginning to add American titles to the database. Because the vast majority of her other works were not translated into English, the WPHP holds a mere five of her more than 100 titles: The Three Monks!!! (1803), The Captive of Valence (1804), Baron de Falkenheim (1807), Mystery Upon Mystery (1808), and The Black Banner; or, the Siege of Clagenfurth (1811).

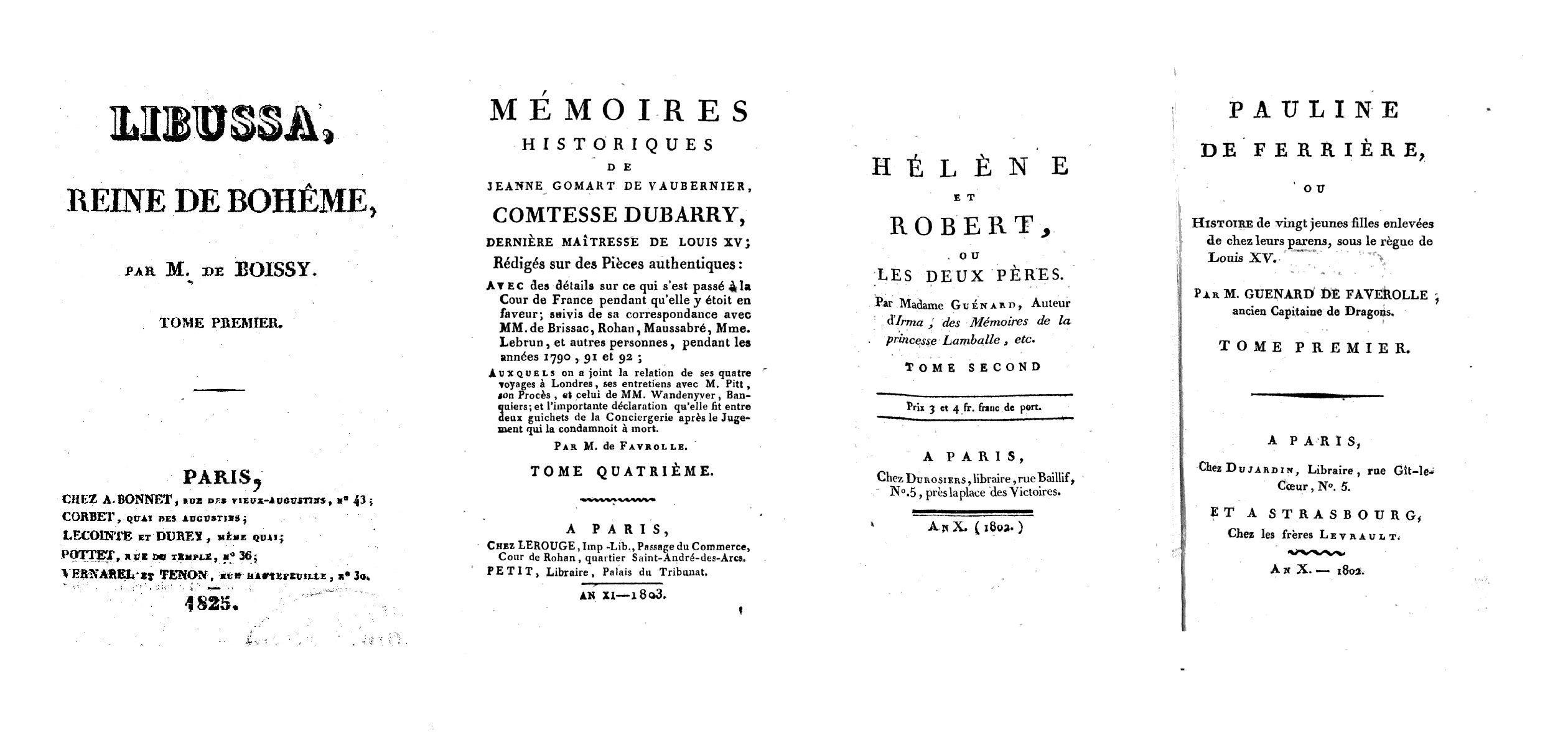

Guénard was almost unbelievably prolific. She produced sentimental, political, moral, educational, and gothic writing, as well as delving into the more licentious and mildly erotic, in the form of novels, histories, and memoirs (although how much of these is fact and how much is fiction is debatable). She published under both her maiden name, Elisabeth Guénard, and Madame Guénard-de-Méré or Madame Guénard Baronne-de-Méré, despite having been married to her 88-year-old cousin in 1774 at the age of 23, rendering her legally Elisabeth Guénard de Brossin de Méré for the entirety of her literary career (French Wikipedia). She also used at least five different pseudonyms; my efforts to keep them straight have been stymied by a lack of resources, but I can confidently include among them Monsieur de Favrolles, A. L. de Boissy, P. L. Boissy, J. H. F. de Geller, and Guenard de Favrolles, as these are indicated alongside their respective titles in her entry in a French dictionary of biography from 1852, Nouvelle biographie universelle depuis les temps les plus reculés jusqu'a nos jours. The few sources available about Guénard suggest that she associated specific pseudonyms with specific genres; while both my lack of French and the lack of available sources and digitizations have made it difficult to parse which pseudonym goes with which genre or style, the association of Monsieur de Favrolles—the name she put to Les Trois Moines—with the more licentious works is fairly widely accepted.

Title pages illustrating Guénard's wide use of pseudonyms. Pictured: Libussa (NCCO); Memoires Historiques de Jeanne Gomart de Vaubernier, Comtesse Dubarry (Google Books); Héléne et Robert (Google Books); and Pauline de Ferriere (Google Books)

The number of pseudonyms she used makes it difficult to assess the full breadth of Elisabeth Guénard’s astounding literary career. While no comprehensive source for her publications appears to exist, her entry in Nouvelle biographie universelle lists no fewer than 107 distinct titles attributed to her between 1799, the year she published her first novel, Lise et Valcourt, and 1829, the year she died. This number does not include new editions, of which there were many, and works republished with new titles, of which there were a few, or the publication of additional volumes and continuations, such as with her political novel, Irma, which dealt with the French Revolution. Antoinette Sol has helpfully untangled the timeline of Irma’s publication, explaining,

Volume one and two, serving as a sort of trial balloon, were published first [in 1799]. For some reason, they were not subject to censure and the sales were encouraging. The third and fourth volume quickly followed. The novel ran to ten editions from 1799 to 1815, not including the pirated runs. It was considered politically dangerous enough in 1810 to have the ninth edition confiscated by the police. In the tenth edition, Guénard adds a fifth and sixth volume. In 1825, Guénard published a three-volume continuation, Triomphe d’une auguste princesse, which brings the total to nine.

If Irma is any indication, the popularity of her publications—not to mention the number of different works—contributes to the difficulty of tracking their subsequent editions. If we trust the Nouvelle biographie universelle, which is admittedly dated but also the most comprehensive source I could find, then over the course of her thirty-year literary career Elisabeth Guénard averaged three new publications a year. What is even more impressive to consider is her output in specific years. While there were some years where Guénard published nothing new—1805, 1815, 1826, 1827—there were also years where she published over five new titles in a year: ten works in 1802, eight in 1803, seven in 1807, and six in 1812, 1817, 1820, 1821, and 1825 each.

The existing scholarship makes it difficult to determine with any degree of certainty the full extent of her career. The sources I was able to find and translate were less than ideal: French Wikipedia, the nearly two-centuries old 1852 Nouvelles biographie universelle, and informal blog posts like Antoinette Sol’s “All that you must know about the French Revolution you can learn from Irma”, published on the What You Must Know About the French Revolution WordPress site. In large part, the difficulty arose from Elisabeth Guénard not having been the subject of English scholarship.

In between bouts of cursing my lack of French and attempting to translate and re-translate Guénard’s French Wikipedia entry, I considered the role of translation and the movement of works between England and France more generally, and how they play into our current and future work with the WPHP. In “Translation, Cross-Channel Exchanges, and the Novel in the Long Eighteenth Century”, Gillian Dow argues that “[the long eighteenth century] is a period in which Anglo-French exchanges shape the development of the novel”—but she also concedes that “most scholars interested in the 18th-century novel are still not interested in translation in context, and most interested in 18th-century translation are not exclusively interested in the novel” (692). My fruitless searches for English scholarship on Guénard confirm Dow’s assessment, especially as Guénard highlights the limitations of our own database’s focus. At the time of writing this spotlight the WPHP is strictly an Anglo-centric database, but we have plans to expand into France. Dow’s commentary on the significance of the relationship between England and France on the novel (and certainly other genres, as well) reinforces our own instincts that collecting quantitative data for books produced in both Britain and the countries with which it exchanged significant amounts of literary material—America and France, to start—is important for understanding the breadth of women’s involvement in print during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. This work on Guénard has pointed towards some of the challenges we will face as we begin to do so. That being said, the gothic tropes included in Guénard’s The Three Monks!!! already confirm on a small scale Dow’s argument that “Anglo-French exchanges shape the development of the novel”—Guénard has clearly engaged with, and is responding to, the tropes made popular by the British and Radcliffean gothic modes (both of which are referred to in Victoria DeHart’s spotlight about Ann Radcliffe, and Kandice Sharren’s spotlight about the Robinsons, a well-known publishing family).

The Three Monks!!!, assuming that it is a reliable translation of Les Trois Moines, is littered with the tropes that typify the gothic mode we are familiar with in British gothic novels. The inclusion of ‘monks’ in the title is a first indication that this text is gothic (Matthew Gregory Lewis’s 1796 The Monk, did, I think, ensure that naming ‘monks’ in titles would no longer suggest genuinely monastic or religious literature), but its exploration of Italy, banditti, sudden and terrifying storms on rivers, subterraneous caverns, abbeys, kidnappings and assassinations cement the point. The novel humorizes the familiar gothic mode even as it capitalizes on that familiarity—every scene that sets itself up as if to instill fear in the reader, recreating the “horrid” moments so typical of gothic novels, almost immediately dispels it with hilarity. A “grotesque” “spectre” of a prior is rendered ridiculous by the assertion that he moves so slowly Anselmo and Dominico cannot walk beside him; Anselmo and Dominico, upon being locked inside a room in the abbey, simply kick the door down to escape—and set it back up against the doorframe again after they return so that the prior, attempting to enter, knocks it over and falls on his rear; and when Anselmo and Dominico hear footsteps in a subterraneous cavern, twice, exploration reveals it is first only their friend Silvino, who they are enormously pleased to see, and second a bag of money and a note (also from Silvino, who appears to greatly enjoy sneaking around subterraneous caverns).

The anticipated—and indeed, necessary—familiarity of Guénard’s audience with the gothic underscores an important point: the mode clearly crossed both national and linguistic boundaries, enough so that the French novelist could subvert familiar tropes popularized by British and Radcliffean gothic novels for comic effect.

We would love to hear from you if you have information about the prolific Elisabeth Guénard—you can comment on her Person Record, or reach out to us on one of our social media accounts (@TheWPHP on Twitter and @womensprinthistoryproject on Instagram). If you’d like to hear more about Elisabeth Guénard’s The Three Monks!!!, we discuss its delightful hilarity in more detail—as well as Catherine Cuthbertson’s 1803 gothic novel Romance of the Pyrenees—in our upcoming podcast episode, “Of Monks and Mountains!!!”, which will be released Wednesday, October 21, 2020 on The WPHP Monthly Mercury podcast.

WPHP Records Referenced

Guénard, Elisabeth (person, author)

Sarrett, H.J. (person, translator)

Benjamin Crosby and Co. (firm, publisher)

The Three Monks!!! (title)

The Captive of Valence (title)

Baron de Falkenheim (title)

Mystery Upon Mystery (title)

The Black Banner; or, the Siege of Clagenfurth (title)

Works Cited

Dow, Gillian. "Translation, Cross-Channel Exchanges and the Novel in the Long Eighteenth Century." Literature Compass, vol. 11, no. 11, November 2014, p. 691–702.

Elisabeth Guénard. French Wikipedia. Retrieved 15 October 2020 from https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%89lisabeth_Gu%C3%A9nard.

Hoefer, M. (Jean Chretien Ferdinand). Nouvelle biographie universelle depuis les temps les plus reculés jusqu'a nos jours. Firmin-Didot, 1852.

Michaud, Louis Gabriel. Biographie universelle ancienne et moderne, vol. 18, p. 38–39. Madame C. Desplaces, 1857.

Sol, Antoinette. "'All that You Must Know About the French Revolutionn you can learn from Irma,' by Antoinette Sol." What You Must Know about the French Revolution: Literature / Les Must de la Revolution francaise: La litterature, 2010, https://whatyoumustknowaboutthefrenchrevolutionli.wordpress.com/2010/02/16/%e2%80%9call-that-you-must-know-about-the-french-revolution-you-can-learn-from-irma%e2%80%9d/.

Garside, Peter, James Raven, and Rainer Schöwerling, eds. The English Novel, 1770–1829: A Bibliographical Survey of Prose Fiction Published in the British Isles. Oxford UP, 2000.

Further Reading

Cohen, Margaret and Carolyn Dever, eds. The Literary Channel: The International Invention of the Novel. Princeton UP, 2002.

Dejean, Joan. Tender Geographies: Women and the Origins of the Novel in France. Columbia UP 1991.

Doig, Kathleen Hardesty and Dorothy Medlin, eds. British‐French Exchanges in the Eighteenth Century. Cambridge Scholars, 2007.

Dow, Gillian, ed. Translators, Interpreters, Mediators: Women Writers 1700–1900. Peter Lang, 2007.

Mandal, Anthony. Jane Austen and the Popular Novel. Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2007.

Wright, Angela. Britain, France and the Gothic, 1764–1820: The Import of Terror. Cambridge UP, 2013.