This post is part of our Spooky Spotlight Series, which will run through October 2020. Spotlights in this series focus on Gothic titles, authors, and firms in the database.

Authored by: Kandice Sharren

Edited by: Michelle Levy, Kate Moffatt, Victoria DeHart, and Amanda Law

Submitted on: 10/08/2020

Citation: Sharren, Kandice. "The Romances of Robinsons." The Women's Print History Project, 8 Oct 2020, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/39.

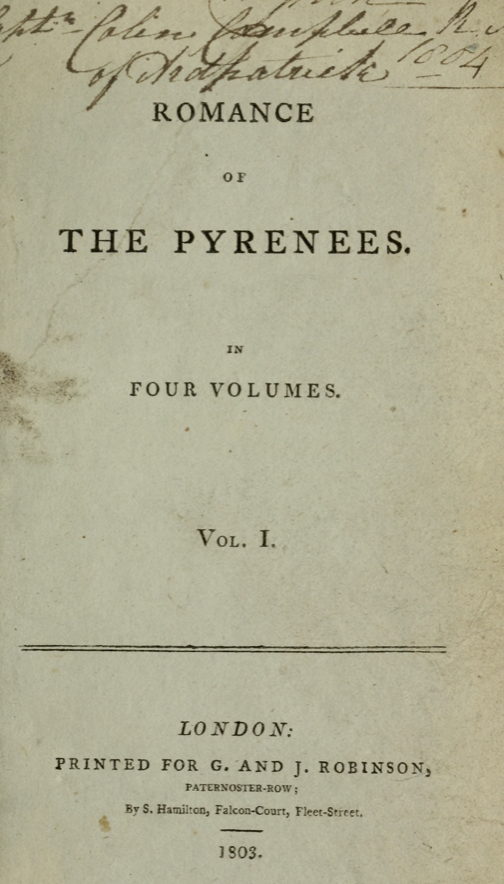

Figure 1. Title page of the first edition of Cuthbertson’s Romance of the Pyrenees (1803). HathiTrust Digital Library.

In 1764 George Robinson entered a partnership with the bookseller John Roberts, and began trading at Addison’s Head, 25 Paternoster Row, where his firm would remain, in different permutations, until 1822. By the 1790s, George, with his son George and brothers John and James, all of whom became partners in 1784, had become one of the most established publishers in London. Between 1790 and 1830, the official name of the Robinson firm changed several times as various family members died and retired: from G. G. J. and J. Robinson to G. G. and J. Robinson in 1794, to G. and J. Robinson in 1802, to George Robinson in 1806, to G. and S. Robinson in 1814, to, finally, Samuel Robinson from 1817 until the firm’s end in 1830.

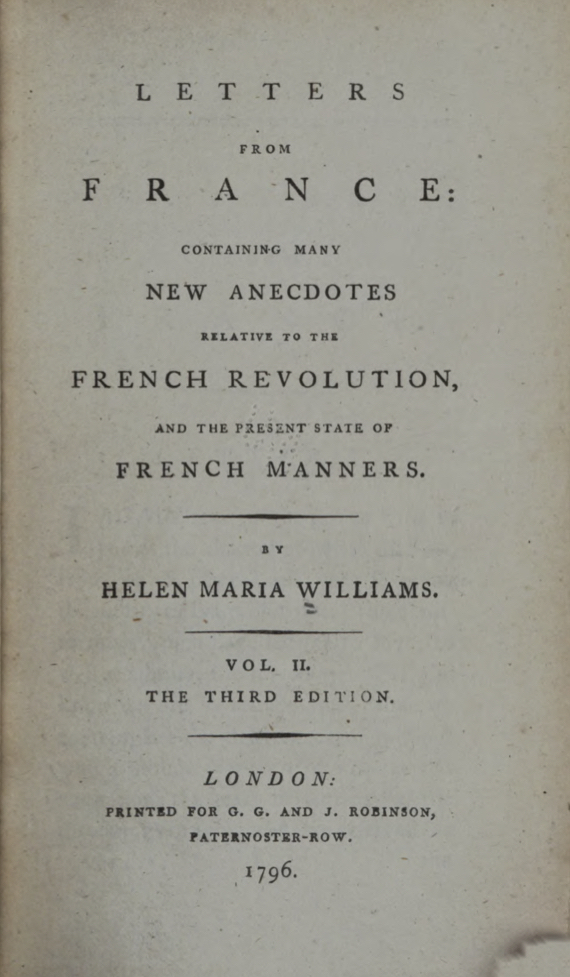

Figure 2. Title page of the third edition of Helen Maria Williams’s Letters from France, Volume II (1795). HathiTrust Digital Library.

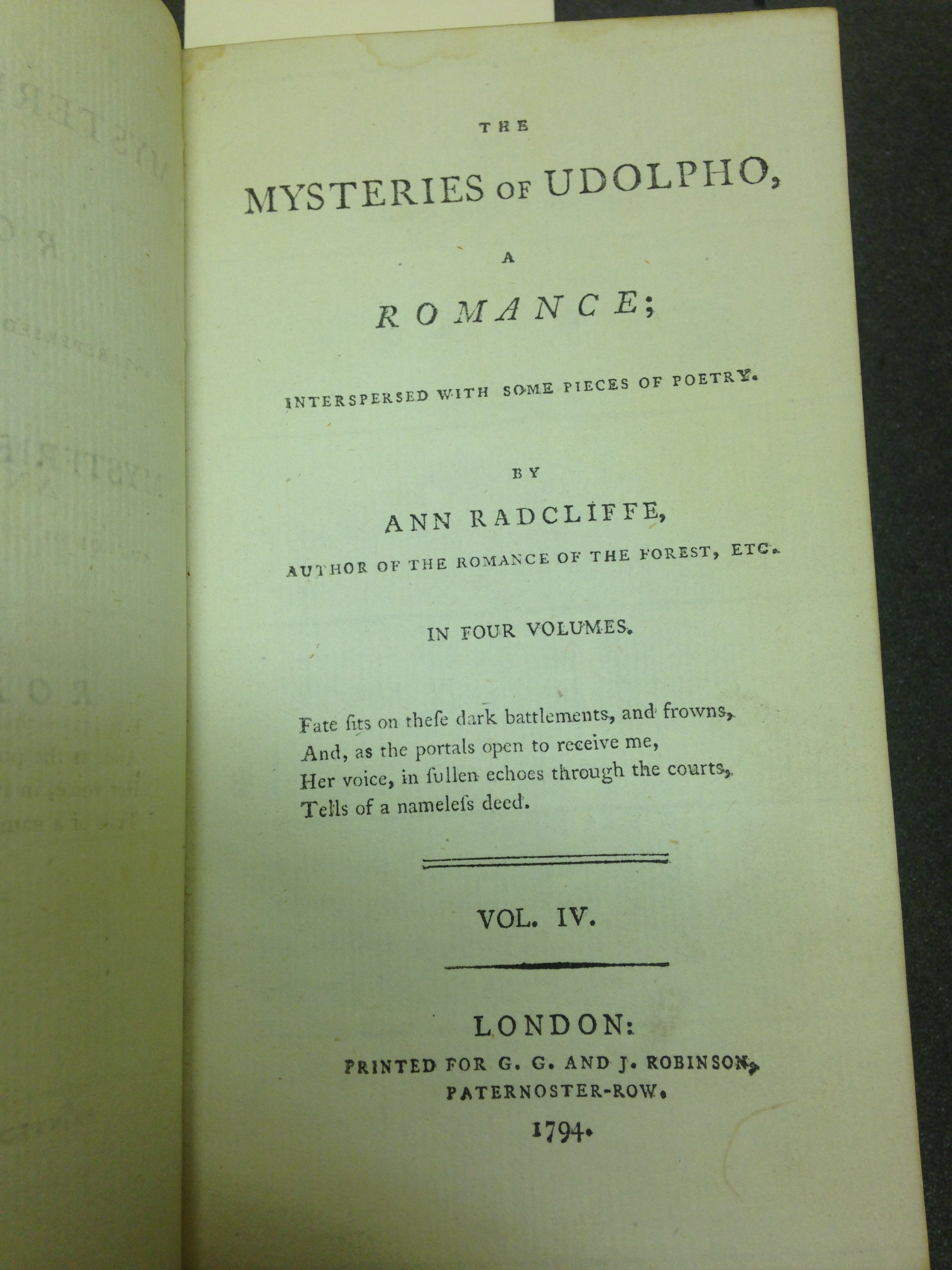

Overall, Robinsons had a reputation for publishing translations, travel memoirs, and political writing; as an increasingly popular genre, fiction also comprised a significant proportion of their publishing lists. During the 1790s the firm established long-standing relationships with reform-minded and radical writers who published in multiple genres, including William Godwin, Elizabeth Inchbald, and Helen Maria Williams, whose translation of Jacques-Henri Benardin de Saint-Pierre’s novel Paul and Virginia (1795) was published alongside the second, third, and fourth volumes of her Letters from France (1790–95), which reported directly on the progress of the French Revolution, and a travel memoir, A Tour in Switzerland (1798). Accordingly, much of the fiction Robinsons published tended to be explicitly political, such as Charlotte Smith’s Desmond (1792) and Godwin’s Caleb Williams (1794); however, the firm also became closely linked to the Radcliffean gothic in the popular imagination after paying Ann Radcliffe £500 for The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794). According to JoEllen Delucia, this change in publisher “elevat[ed] Radcliffe’s work above the novels and tales written by the poorly compensated and primarily female authors who worked with circulating library publishers,” and folded Radcliffe into a community of radical writers that included Godwin, Williams, and Inchbald (289).

Figure 3. Title page of the fourth volume of Radcliffe’s Mysteries of Udolpho (1794). Chawton House Library.

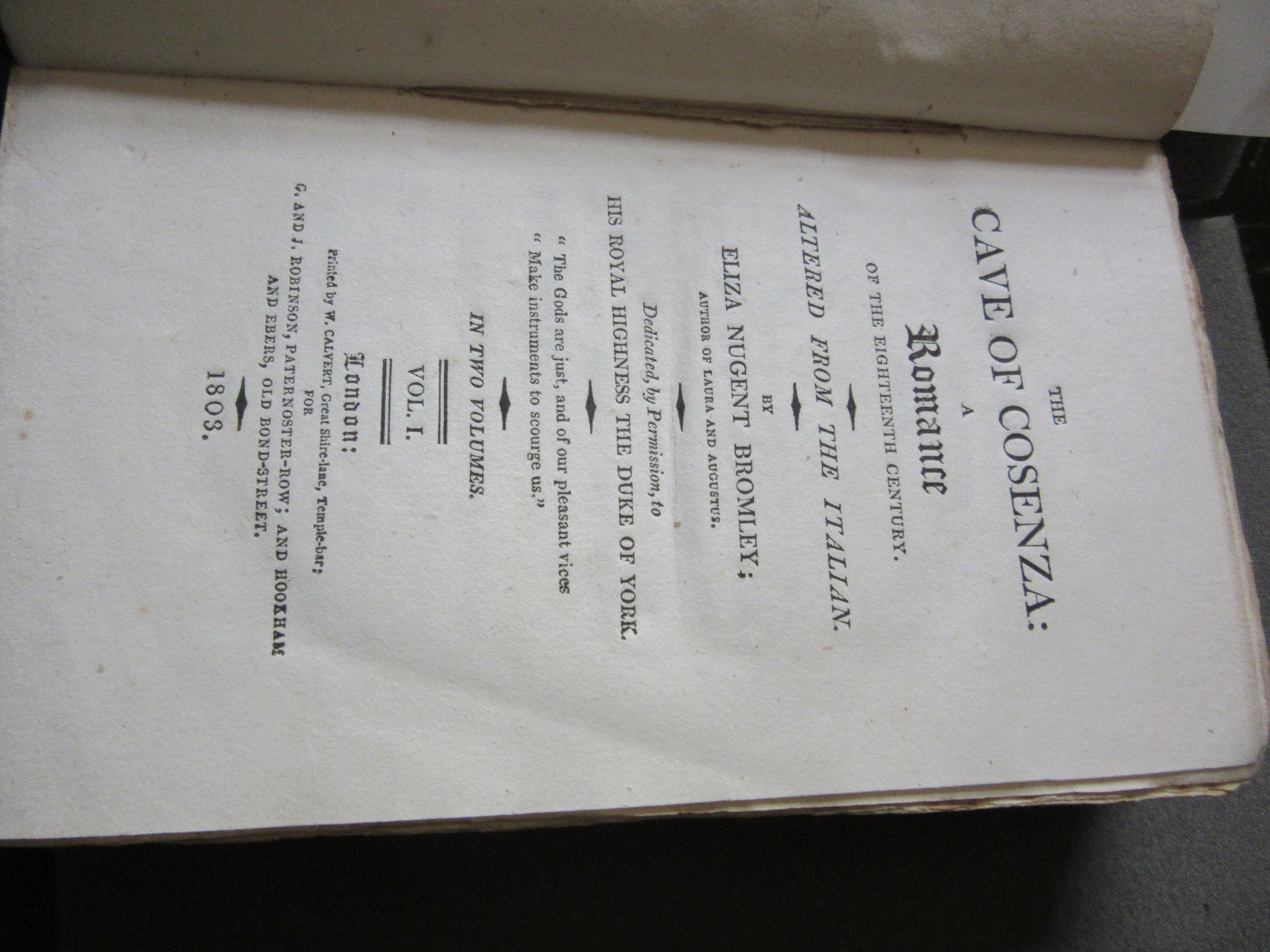

However, the benefits of this association were not only one-sided. Victoria DeHart’s spotlight last week outlined how Radcliffe’s novels were some of the most successful of the 1790s, and how their success had a dramatic effect on the literary marketplace, spearheading a gothic craze. As one of Radcliffe’s publishers, Robinsons profited from the commercial and critical success of The Mysteries of Udolpho, which shaped their strategy for publishing new fiction during the subsequent decades. While the firm continued to publish political writing, such as Mary Wollstonecraft’s Posthumous Works (1798; to be featured in Michelle Levy’s upcoming spotlight) and Elizabeth Hamilton’s Memoirs of Modern Philosophers (1800), translations like Germaine de Stael-Holstein’s Delphine (1803), and travel memoirs (including Radcliffe’s own travel memoir, A Journey Made in the Summer of 1794, through Holland and the western frontier of Germany, in 1795), a new genre was brought to the fore: the gothic romances that Radcliffe had popularized. Titles such as Theodosius de Zulvin, the Monk of Madrid (1802) by George Moore, The Cave of Cosenza (1803) by Eliza Nugent Bromley, and the anonymous 1808 novel The Monks and The Robbers invoked many of the Gothic motifs present in Radcliffe’s romances, such as Catholic monks, medieval castles where women were held captive, and banditti-ridden Spanish and Italian landscapes.

Figure 4. Title page of Bromley’s The Cave of Cosenza (1803). Chawton House Library.

Robinsons’ desire to invoke the Radcliffean gothic in subsequent publications is most clearly on display in the firm’s decade-long relationship with the now largely forgotten novelist Catherine Cuthbertson, one of the most successful Radcliffe imitators of the early nineteenth century. The title of Cuthbertson’s first novel, Romance of the Pyrenees (1803), echoes Radcliffe, with its evocation of the landscape described in detail in The Mysteries of Udolpho. These resonances are muted but still present in the titles of Cuthbertson’s next two novels, Santo Sebastiano (1806) and The Forest of Montalbano (1810), where Spanish and Italianate names and locations are invoked, indicating how Robinsons sought to capitalize on its connection to Radcliffe’s most iconic novel.

Although Romance of the Pyrenees did not have a promising launch—most of the copies of the first edition were destroyed in S. Hamilton’s warehouse fire in 1804, which bankrupted Robinsons—in the long run Cuthbertson’s strategy was a success, and both Cuthbertson’s novel and Robinsons ultimately recovered. That year, the second edition appeared as a serialized reprinting in The Lady’s Magazine (meaning it is not included in our database). By 1822, it had gone into four further editions (third , fourth), including one American reprinting in New Hampshire and a joint issue by Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, and A. K. Newman and Co. (the successor to the popular but widely derided Minerva Press) in 1822. It continued to be reprinted into the middle of the nineteenth century, with at least two further British editions appearing into the 1840s and one further American edition appearing in 1854. Likewise Santo Sebastiano went into four London editions (second, third, and fourth) and one American edition by 1820, and was also reprinted in the 1840s. The commercial success of Cuthbertson’s novels depended on a readership familiar with both Radcliffe’s fiction and Radcliffe’s publishers: the imprints on Cuthbertson’s novels—which implied that they were printed for the publisher of The Mysteries of Udolpho—acted as a guarantee of quality not to be found in the productions of circulating library publishers. Therefore, even though Cuthbertson’s fiction was clearly marked and marketed as derivative of Radcliffe’s, Robinsons’ imprint granted the text greater prestige.

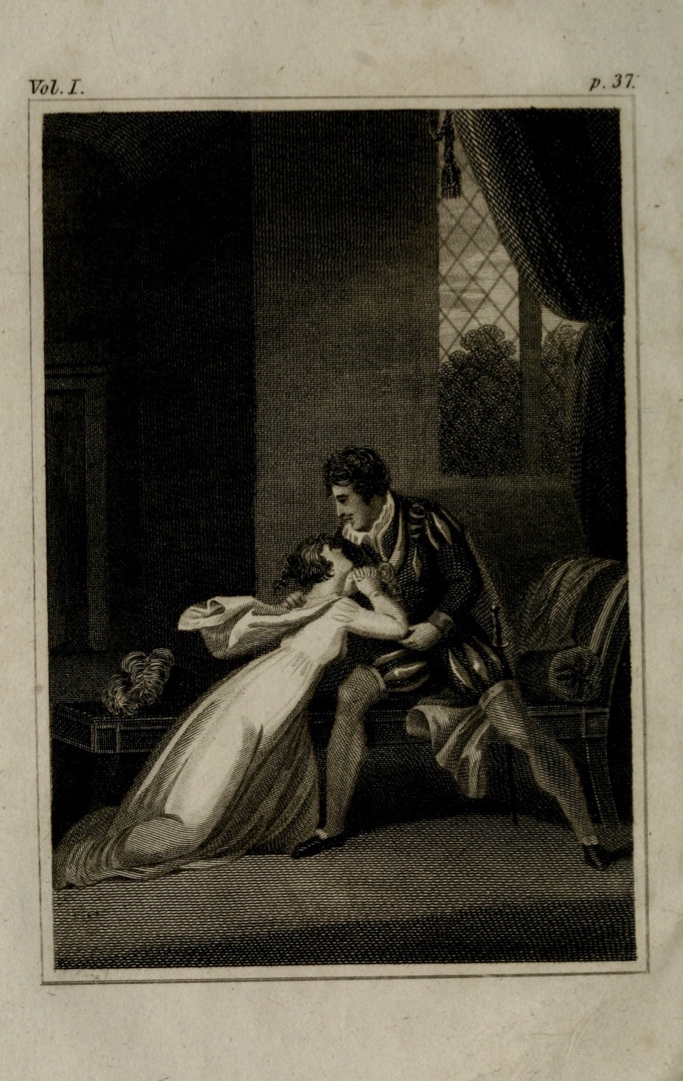

Figure 5. Frontispiece to the third edition of Romance of the Pyrenees (1807). HathiTrust Digital Library.

But this strategy had its limits. Beginning with The Forest of Montalbano, all of Cuthbertson’s subsequent works failed to move beyond a first edition, which spelled the end of Cuthbertson’s thus-far exclusive relationship with Robinsons: her fourth novel, Adelaide; or, the Counter-Charm was published jointly with Cradock and Joy, who would publish her fifth novel, Rosabella; or, A Mother’s Marriage (1817). Cuthbertson’s more subdued success after 1810 is part of a general trend: Anthony Mandal has noted an overall “fall from 199 Gothic titles published in the 1800s (25.6 per cent [of all new fiction published in Britain]) to 89 in the 1810s (13.3 per cent), waning to 6.6 per cent at its lowest in 1814,” which mirrored an overall decline in new fiction during the latter decade (22). Robinsons’ fiction output declined even more than the average; between 1800 and 1809 they published twenty-nine new works of fiction, while in the following decade they only published ten—between 1816 and 1820 they published no new fiction at all. While new editions of both Radcliffe and Cuthbertson’s works appeared in the 1820s, suggesting that the public’s taste for gothic romances had not completely disappeared, they appeared under the imprint of other publishers; the link between Robinsons and the Radcliffean gothic had been severed.

WPHP Records Referenced

George Robinson and John Roberts (firm, publisher and bookseller)

George Robinson [ii] (firm, publisher and bookseller)

George, George, John, and James Robinson (firm, publisher and bookseller)

George, George, and John Robinson (firm, publisher and bookseller)

George and John Robinson (firm, publisher and bookseller)

George Robinson [iii] (firm, publisher and bookseller)

George and Samuel Robinson (firm, publisher and bookseller)

Samuel Robinson (firm, publisher and bookseller)

Travel/Tourism/Topography (genre)

Political Writing (genre)

William Godwin (person, author and editor)

Elizabeth Inchbald (person, author)

Letters from France, Volume II (title, third edition)

Helen Maria Williams (person, author and translator)

Paul and Virginia (title)

Letters from France (title)

Letters from France, Vol. II (title)

Letters from France, Vol. III (title)

Letters from France, Vol. IV (title)

A Tour in Switzerland (title)

Charlotte Smith (person, author)

Desmond (title)

Ann Radcliffe (person, author)

The Mysteries of Udolpho (title)

"The Enchanting Ann Radcliffe" (person spotlight by Victoria DeHart)

Mary Wollstonecraft (person, author)

Posthumous Works of the Author of the Vindication of the Rights of Woman (title)

Elizabeth Hamilton (person, author)

Memoirs of Modern Philosophers (title)

Germaine de Stael-Holstein (person, author)

Delphine (title)

A Journey Made in the Summer of 1794, through Holland and the western frontier of Germany (title)

The Cave of Cosenza (title)

Eliza Nugent Bromley (person, author)

Catherine Cuthbertson (person, author)

The Romance of the Pyrenees (title, first edition)

Santo Sebastiano (title, first edition)

Forest of Montalbano (title, first edition)

S. Hamilton (firm, printer)

The Romance of the Pyrenees (title, third edition)

The Romance of the Pyrenees (title, fourth edition)

The Romance of the Pyrenees (title, American edition)

The Romance of the Pyrenees (title, fifth edition)

Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy (firm, publisher)

A.K Newman and Co. (firm, publisher)

Minerva Press (firm, publisher)

Santo Sebastiano (title, second edition)

Santo Sebastiano (title, third edition)

Santo Sebastiano (title, fourth edition)

Santo Sebastiano (title, American edition)

Adelaide; or, the Counter-Charm (title)

Cradock and Joy (firm, publisher)

Rosabella; or, A Mother’s Marriage (title)

Works Cited

DeLucia, JoEllen. “Radcliffe, George Robinson and Eighteenth-Century Print Culture: Beyond the Circulating Library.” Women’s Writing, vol. 22, no. 3, 2015, pp. 287–99.

Mandal, Anthony. Jane Austen and the Popular Novel. Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2007.

Further Reading

Batchelor, Jennie. “Finding the Mysterious Miss Cuthbertson in the Lady’s Magazine.” The Lady’s Magazine (1770–1818): Understanding the Emergence of a Genre (blog), 2016, https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/ladys-magazine/2016/04/17/finding-the-mysterious-miss-cuthbertson-and-the-ladys-magazine/.

Bentley, G. E. “Copyright Documents in the George Robinson Archive: William Godwin and Others 1713-1820.” Studies in Bibliography, vol. 35, 1982, pp. 67–110.

Bentley, G. E. Jr. "Robinson family (per. 1764–1830), booksellers." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford UP, 2008, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/74586.

Garside, Peter. “The English Novel in the Romantic Era: Consolidation and Dispersal.” The English Novel, 1770–1829: A Bibliographical Survey of Prose Fiction Published in the British Isles, edited by Peter Garside, James Raven, and Rainer Schöwerling, Oxford UP, 2000, pp. II: 15–103.

Raven, James.The Business of Books: Booksellers and the English Book Trade, 1450–1850. Yale UP, 2007.