This post is part of Around the World with Six Women: A Travel Writing Spotlight Series, which will run through August 2021. Spotlights in this series focus on travel writing by women in the database.

Authored by: Amanda Law

Edited by: Michelle Levy and Kandice Sharren

Submitted on: 08/27/2021

Citation: Law, Amanda. "Describing India, China, and the Shores of the Red Sea: Emma Roberts and British Literature on Asia." The Women's Print History Project, 27 August 2021, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/86.

Figure 1. Views in India, China, and the Shores of the Red Sea (1835) title page. Google Books.

In 1828, writer and editor Emma Roberts (1791/94?–1840) travelled with her sister and her sister’s husband to India, where her brother-in-law was stationed as an officer in Bengal. She spent 1829 and 1830 travelling between the upper province stations of Agra, Cawnpore, and Etawa (Hale 885) before moving to Kolkata in 1831 after her sister’s death. In the upper provinces, she wrote descriptive poetry, stories, and essays, which were compiled and published as a collection titled Oriental Scenes, Dramatic Sketches and Tales, with Other Poems (1830). As Hanieh Ghaderi notes in her spotlight on Eliza Fay, this book, along with Fay’s Original Letters from India (1817) is one of the only titles in the WPHP published in Kolkata. Once in Kolkata, Roberts edited and wrote for the periodical the Oriental Observer. Unfortunately, Roberts’s health began to fail, and she returned to England in 1833 (Gorman 1013).

Figure 2. Views in India, China, and the Shores of the Red Sea (1835) half-title page. British Library.

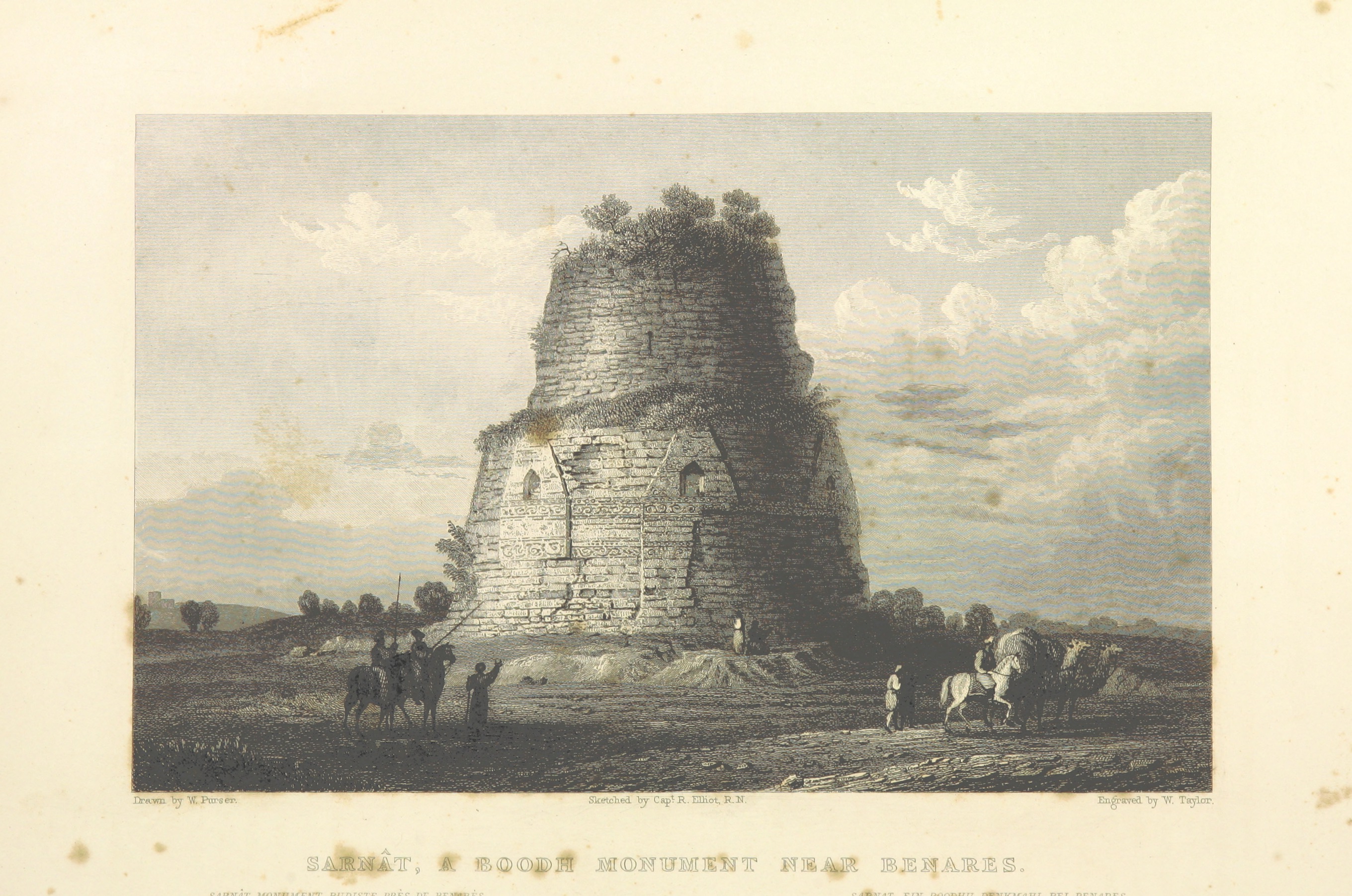

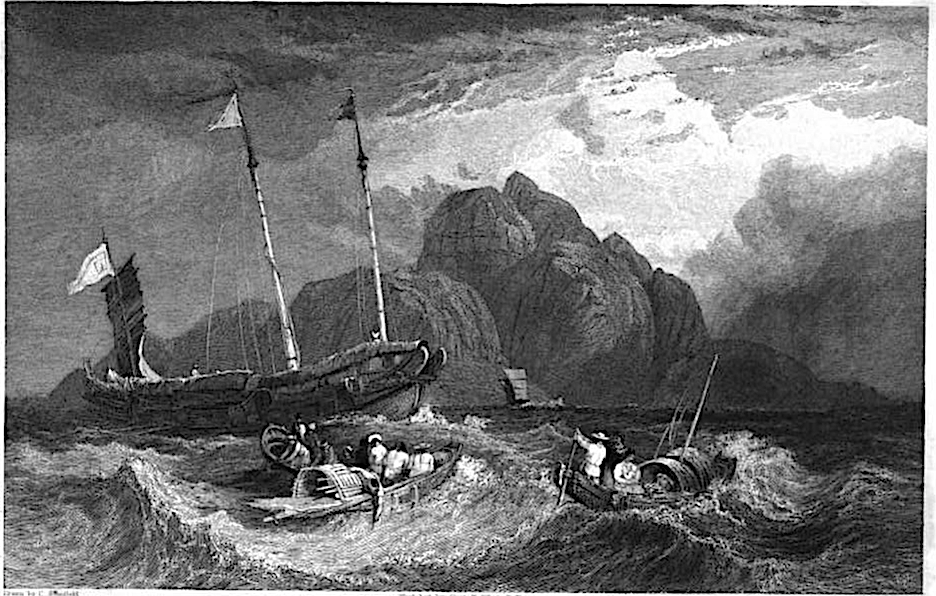

Roberts continued to edit and write upon her return to England, editing publications such as Maria Eliza Rundell’s A New System of Domestic Cookery, beginning from the sixty-fourth edition (read more about this title in Michelle Levy’s spotlight), and a book of poems by Letitia Landon, with whom she had become close friends at school (Hale 885). Most notably, though, Roberts wrote extensively about India, China, and the Middle East. The publishing firm H. Fisher, P. Fisher, and P. Jackson commissioned her to compile the letterpress for the 1833 title Views in the East: comprising India, Canton, and the Shores of the Red Sea: with historical and descriptive illustrations. By Captain Robert Elliot, R. N. and hired her again to write new descriptions for the 1835 second edition, Views in India, China, and on the shores of the Red Sea; Drawn by Prout, Stanfield, Cattermole, Purser, Cox, Austen, &c. from original sketches by Commander Robert Elliott, R.N.; with descriptions by Emma Roberts. This spotlight focuses on the 1835 Views in India, China, and on the Shores of the Red Sea rather than the 1833 first edition because Roberts’s authorial presence is more distinct in the second edition. Along with being definitively listed as a contributor in the full title, Roberts includes a new preface that speaks to her intentions and reflections as a travel writer.

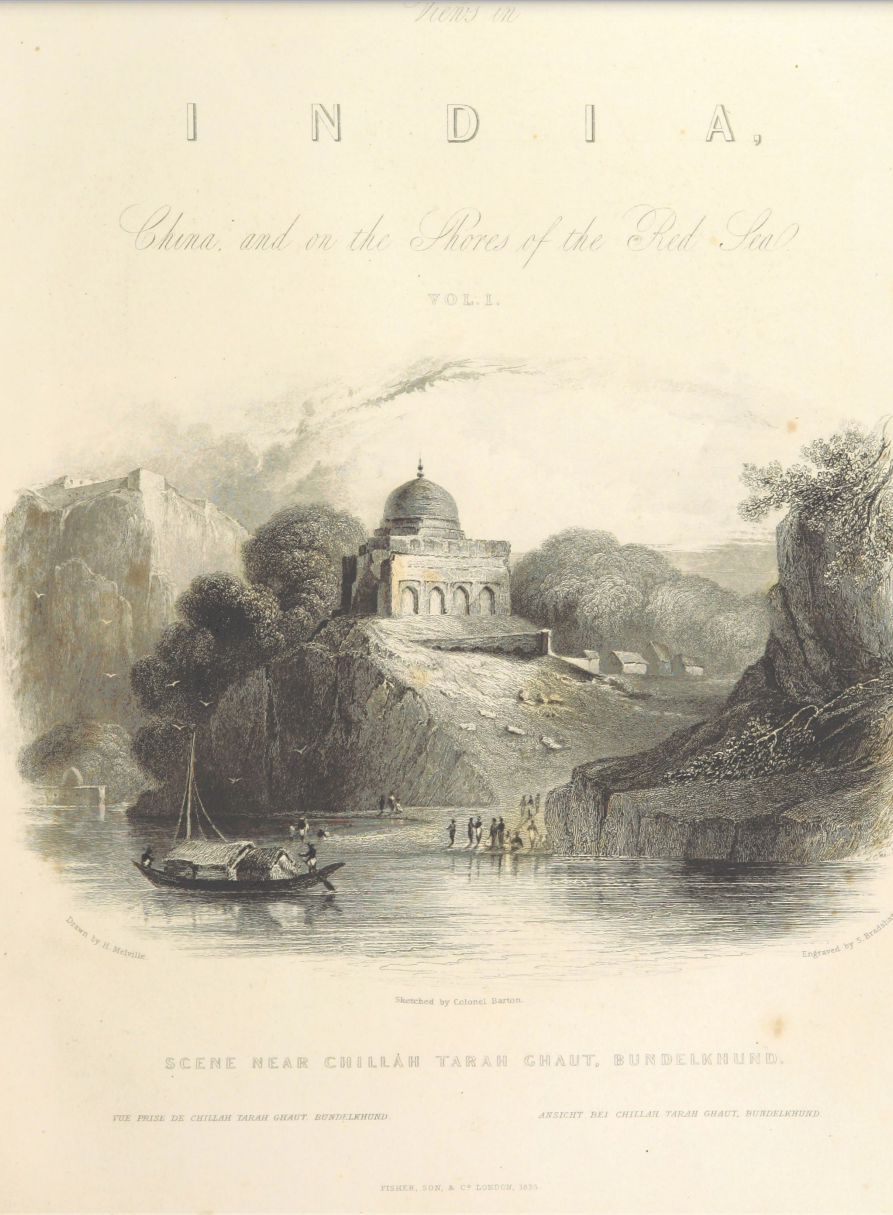

Figure 3. Thubare (Arabian Coast); S. Austin, illustrator; William Miller, engraver; 1835. Google Books.

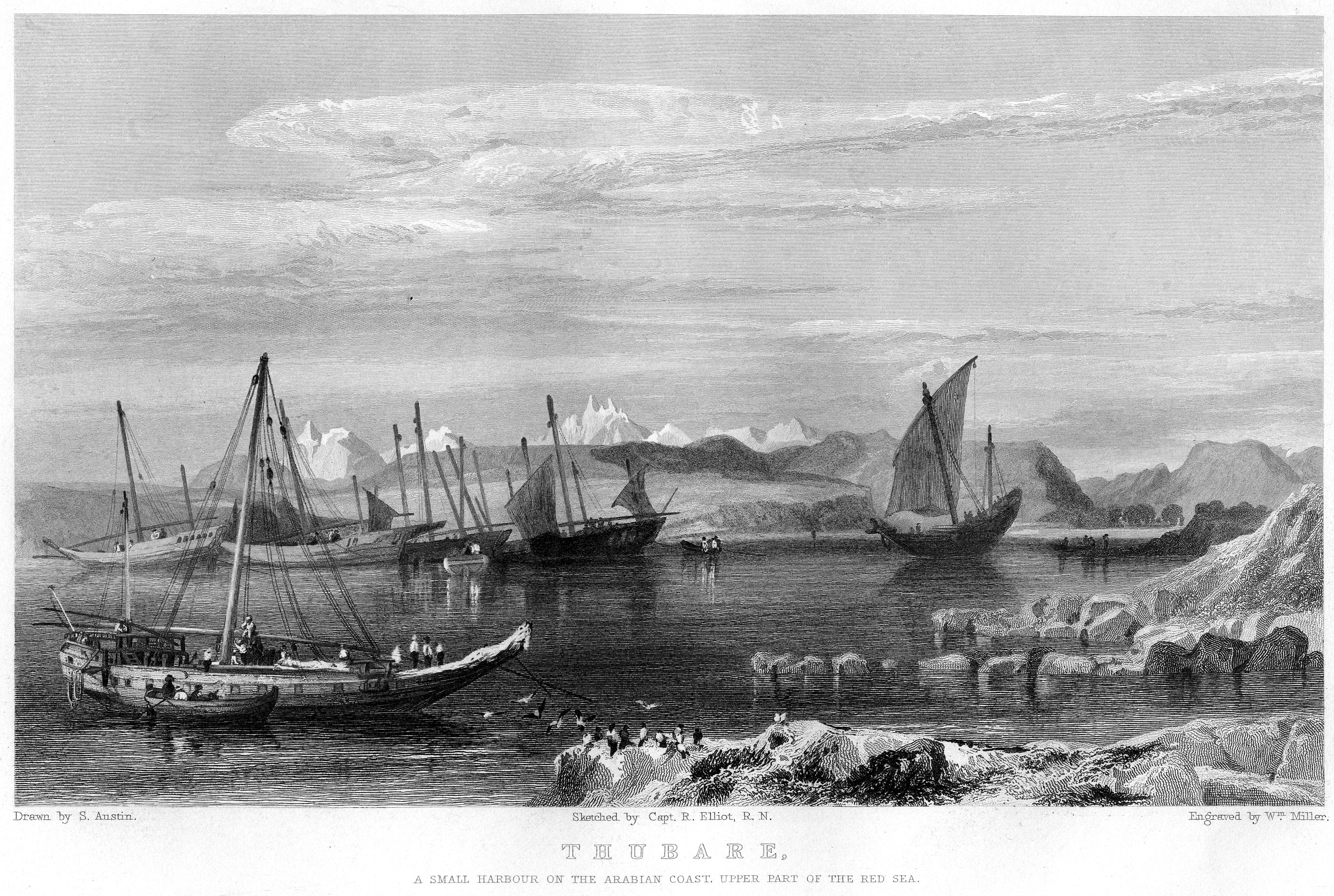

The publication of Views in India, China, and on the Shores of the Red Sea features the sixty-seven engravings that populate the two volumes. The full title itself highlights the artists involved in the illustrations before noting Roberts’s written contribution. Reviews of the book highly praised the visual aspects but rarely mentioned the written text accompanying the illustrations. For example, a review of the first part of the sketches in the 4 September 1830 issue of The Athenaeum deemed it a “valuable work” for illustrations that were “alone worth the money as a work of art” (557). Another review in the July 1831 issue of the Metropolitan offhandedly praised the descriptions, stating that it was “a very beautiful as well as instructive work,” but ultimately landed on commending the illustrations, stating that “[t]he public are greatly indebted to Captain Elliot for this work, which no lover of the arts will be without, for the very superior style in which it is got up” (116). Although public reception and the publishers themselves focused on highlighting the engravings in Views in India, China, and on the Shores of the Red Sea, Roberts’s text deserves more attention, as she presents a significant critique of the elitist nature of literature on the East.

In the preface to Views in India, China, and on the Shores of the Red Sea, Roberts registers how the general reader faces multiple barriers in the field of travel writing about Asia and attempts to position her own work against these obstacles. She writes,

The fields of Oriental literature, until very lately, have been almost exclusively occupied by the researches of learned men, whose lucubrations, though of the highest value, are not adapted to the general reader; while a vast quantity of information, of a more popular kind, remains locked up in expensive quartos, and is consequently inaccessible to a large portion of the community.

Roberts frames literature on Asia as a field for privileged individuals, either because they have specialized knowledge or because they can afford to pay for, or can otherwise access, “expensive quartos.” Contesting the exclusionary nature of the literature on Asia, Roberts positions her own writing as overcoming some of these barriers. She continues in the preface,

The attempt, therefore, to remove some of the difficulties attendant upon an acquaintance with the numerous objects of interest and attention with which our Indian possessions abound, will doubtless prove acceptable to all inquiring minds; and though the plan of the present work does not admit of any detailed account of the various cities and provinces illustrated in the accompanying engravings, nothing has been omitted which the limits would allow, calculated to excite interest, and to induce the reader to enter more deeply into the study of Indian history.

As Nigel Leask notes in his chapter about women travel writers in British India, a “large number of women travel writers [were] now contending for positions in the literary field” (204). He attributes this surge to “[t]he increasing absorption of travel writing into the literary sphere from the 1820s . . . render[ing] specialist scientific knowledge less necessary for travel writers in general, a fact which empowered many women authors” (204). When Roberts concedes that her written descriptions do not contain the most detailed accounts of the cities and provinces, but are rather intended to foster interest and fascination, she demonstrates this move away from scientific knowledge towards more accessible information within the genre of travel writing.

Figure 4. Sarnât (near Benares); William Purser, illustrator; W. Taylor, engraver; 1835. British Library.

It is important to note that while Roberts attempts to diverge from the elite knowledge conveyed in British accounts of Asia, an imperialistic attitude still bleeds into her writing. Quoting Indira Ghose, Leask argues that European women writers, such as Roberts, “occupied the amphibious subject position . . . of being ‘colonised by gender, but colonisers by race” (204). By setting herself apart from the work of learned men, Roberts makes a point to push against the gendered constraints on this field of writing, but by considering her subject “Indian possessions” she aligns herself with the imperialistic. In the section on Canton, Roberts cautions against forming opinions on entire populations and cultures based on minimal information, stating that “[u]nfortunately, our scanty knowledge of the tone of morals in the interior [of China], rendered us but too apt to form our estimate of the whole from that which comes our own observation” (14). While this statement reads as Roberts condemning imperialistic tendencies to objectify and stereotype large groups of people, elsewhere she engages in similar judgments.

Figure 5. Tiger Island (Canton River); C. Stanfield, illustrator; Edward Goodall, engraver; 1835. Google Books.

Despite her wariness of the existing literature on the East, Roberts reveals in the preface that she consults this specialized knowledge to write her own descriptions. Immediately following her thoughts on “the fields of Oriental literature,” she states that “[m]any of the scenes described in the following pages are familiar to the writer; and she has spared no pains in procuring information from the most authentic sources, concerning places which she had no opportunity of visiting in person” (Preface). While she points out that she has personally travelled through several of the locations she describes, she also emphasizes the sources she consulted to supplement her writing. The preface concludes with Roberts listing these sources, including “extracts from the translation of a Persian MS., and the latest descriptions of Canton, taken from a periodical published in China, of which very few copies have found their way into [England]” (Preface). She then continues to thank George Bennett, Esq., Sir Alexander Johnstone, and “the Members of the Asiatic Society, for the access granted to the library of their establishment” (Preface). Although Roberts criticizes these societies for their exclusivity, she also relies on them for the content of her writing.

From the beginning of her writing career, Roberts’s work had heavily depended on her research. In her biography on Roberts, Sarah Josepha Hale notes that “[w]hile prosecuting her researches for her first literary performance [Memoirs of the Rival Houses of York and Lancaster (1827)], [Roberts] evinced so much diligence and perseverance, that the officers of the British Museum, where she was accustomed to study, were induced to render her every assistance in their power” (885). Taken altogether, Roberts’s preface does not seem to condemn research and erudition in itself, but rather how they can exclude the general and non-elite reader. Roberts’s solution is to position herself as a translator of experience and research for the general reader, using the malleable genre of travel literature to achieve this end.

WPHP Records Referenced

Roberts, Emma (person, author)

Oriental Scenes, Dramatic Sketches and Tales, with Other Poems (title)

"Agency in Empire: Eliza Fay in India" (spotlight by Hanieh Ghaderi)

Fay, Eliza (person, author)

Original Letters from India (title)

Rundell, Maria Eliza (person, author)

A New System of Domestic Cookery (title, first edition)

"A New System of Domestic Cookery: the 19th century's best-selling cookbook" (spotlight by Michelle Levy)

Landon, Letitia Elizabeth (person, author)

H. Fisher, P. Fisher, and P. Jackson (firm, publisher)

Memoirs of the Rival Houses of York and Lancaster (title)

Works Cited

Buckingham, James Silk, editor. “Views in the East, Comprising India, Canton, and the Shores of the Red Sea.” The Athenaeum, 4 Sept. 1830, p. 557.

Gorman, Anita G. “Roberts, Emma (c. 1793-1840).” Literature of Travel and Exploration: An Encyclopedia, edited by Jennifer Speake, vol. 3, Taylor & Francis, 2003, pp. 1012–1014.

Hale, Sarah Josepha. “Roberts, Emma.” Woman's Record; or Sketches of All Distinguished Women, from The Creation to A. D. 1854. Arranged in Four Eras. With Selections from Female Authors of Every Age, 2nd ed., Harper & Brothers, 1855, p. 885.

Leask, Nigel. “Domesticating Distance: Three Women Travel Writers in British India.” Curiosity and the Aesthetics of Travel-Writing, 1770-1840: 'from an Antique Land', Oxford UP, 2002, pp. 203–242.

Marryat, Frederick, and James Grant , editors. “Views in the East; Comprising India, Canton, and the Shores of the Red Sea, from the Sketches of Captain ROBERT ELLIOT, R. N.” Metropolitan: a Monthly Journal of Literature, Science and the Fine Arts, 1831-1832, July 1831, p. 116.

Roberts, Emma, and Robert Elliott. Views in India, China, and on the Shores of the Red Sea; Drawn by Prout, Stanfield, Cattermole, Purser, Cox, Austen, &c, from Original Sketches by Commander Robert Elliott, R.N. With Descriptions by Emma Roberts. 2nd ed., H. Fisher, R. Fisher & P. Jackson, 1835.