Authored by: Sara Penn

Edited by: Michelle Levy

Submitted on: 02/25/2021

Citation: Penn, Sara. "The Female Spectator: The First Periodical By and For Women." The Women's Print History Project, 25 February 2021, https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/63.

Figure 1. Vol. 2 title page of the First London edition. HathiTrust Digital Library.

Considered one of the most versatile authors in the eighteenth century, Eliza Haywood (1693?–1756) was a poet, translator, playwright, and journalist, as well as an actress and bookseller. Her Female Spectator (1744–46) is known as the first periodical by and for women and a landmark in women’s literary history. Much of what we know about Haywood and her works is a result of Patrick Spedding’s A Bibliography of Eliza Haywood and Kathryn R. King’s A Political Biography of Eliza Haywood.

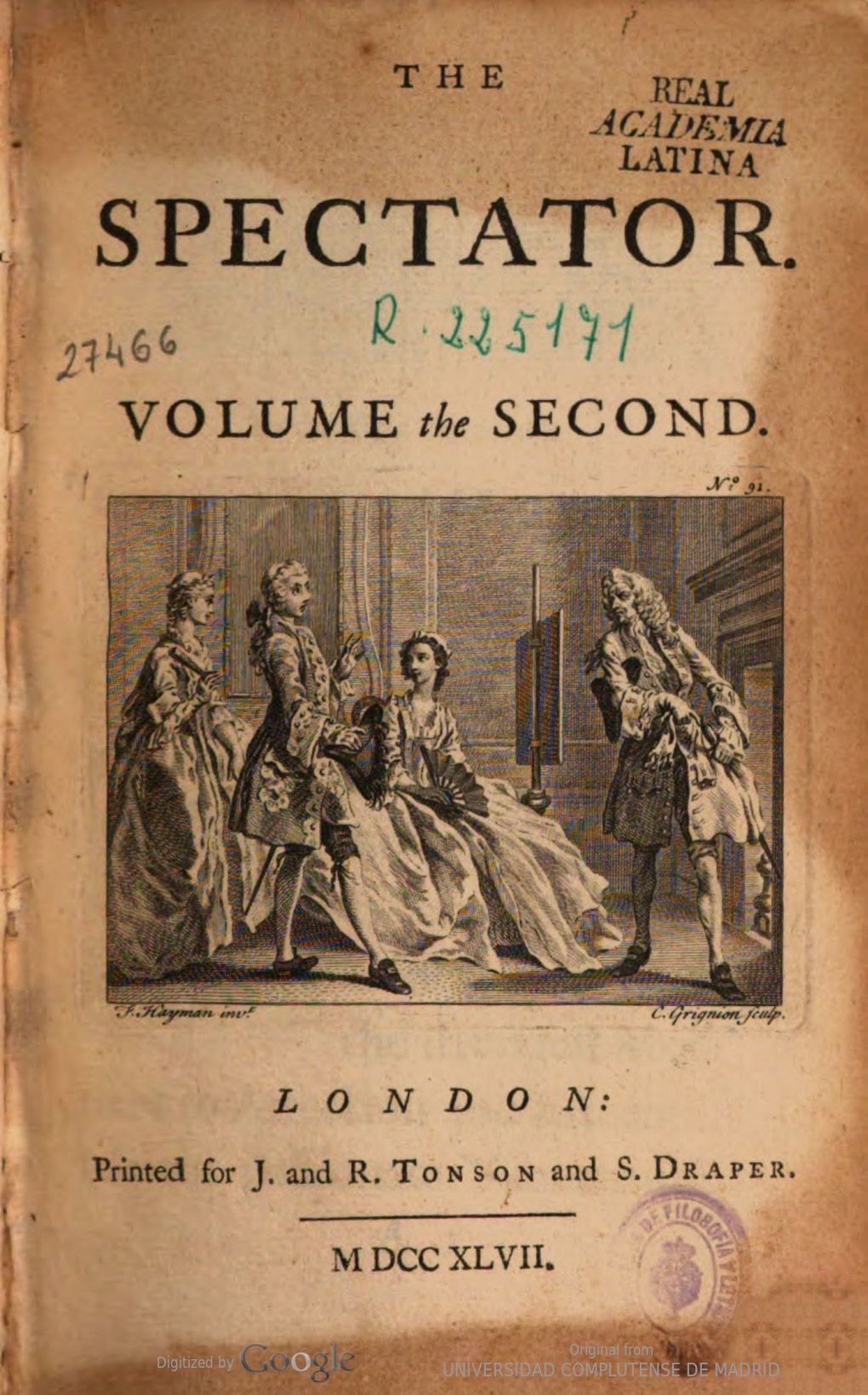

Having established herself as a writer of amorous fiction from the booming success of her first novel, Love in Excess; or, The Fatal Inquiry (1719), Haywood was also a target of satire and criticism, particularly by Alexander Pope, in his 1728 Dunciad. After a decade-long hiatus in the 1730s, Haywood anonymously put forth The Female Spectator from April 1744 to May 1746, seemingly likening her periodical after, and explicitly alluding to, Richard Steele and Joseph Addison’s Spectator (1711–12,14), a highly influential publication of three decades earlier. Dominating early eighteenth-century periodical culture, The Spectator was a literary journal of politics, literature, and art, fostering polite debate through moral essays, miscellanies, and prose devoted to men of high social stations. Bridging the gap between women and the androcentricity of Steele and Addison's journal, Haywood’s Female Spectator became a pioneering journal addressed to women and authored by one.

Her Spectator is added to the WPHP with renewed funding that allows us to extend our data earlier than our previous threshold of 1750. With data collection now going back to 1700, we have decided to include Haywood’s fascinating periodical as one of the first of many works published within this new time frame.

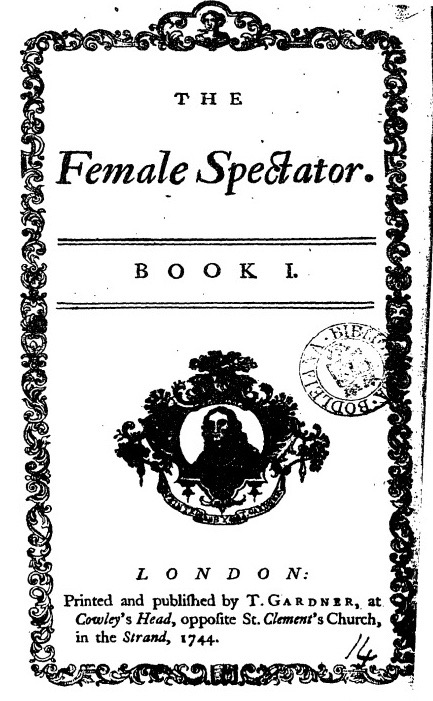

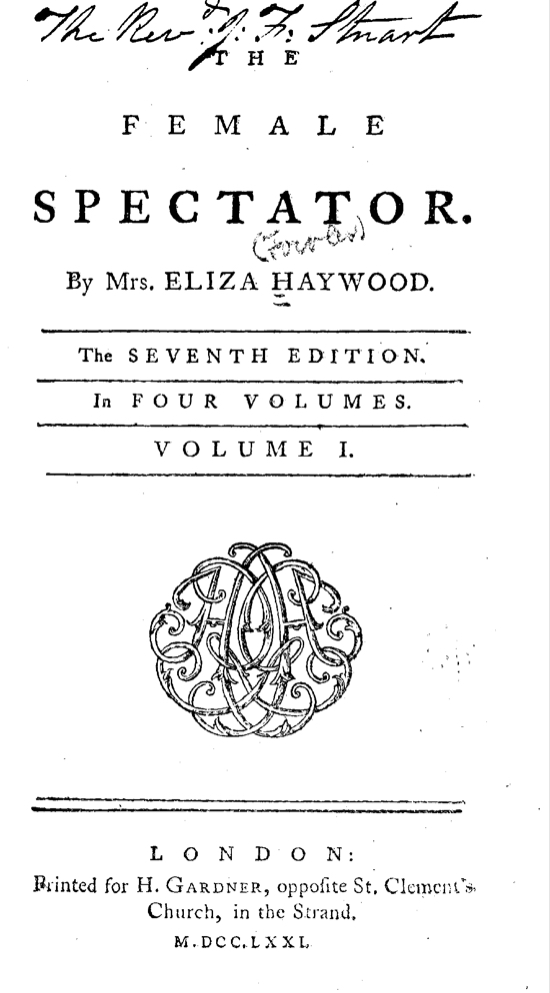

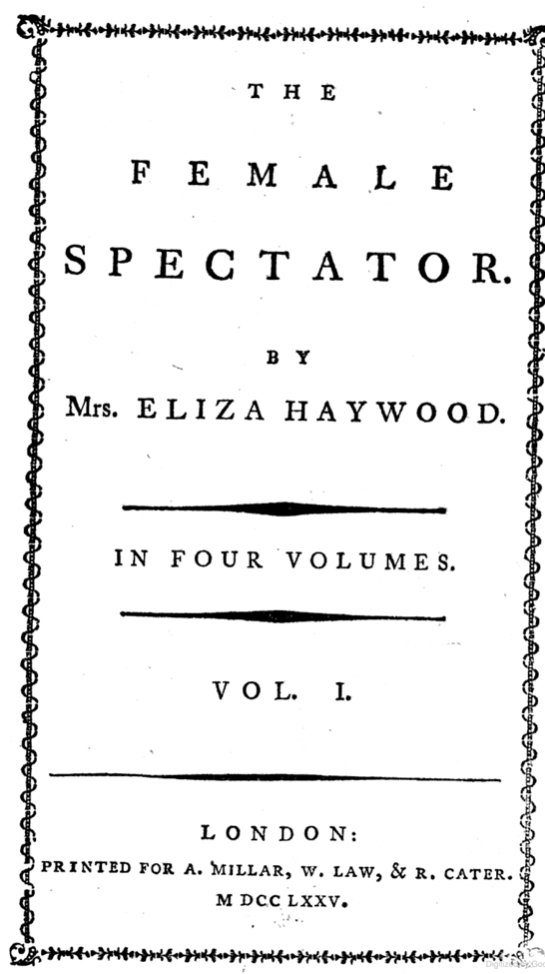

Figures 2 and 3. Vol. 1 title pages of the first (1744) and second (1747) London editions.

Haywood never acknowledged authorship of her Spectator during her lifetime. As an actress, she “was not entirely respectable” in the public sphere due to her more ostentatious roles in the theatre (King 113), and her anonymity in The Female Spectator, as seen in these titles pages, allowed her to meaningfully engage with London affairs without prejudice. Indeed, Haywood’s association with her Spectator was only made known in her obituary (in 1756, a decade after its publication), and was widely accepted to have been her work throughout the eighteenth century.

Printed and published by Thomas Gardner in twenty-four monthly installments, the periodical consisted of about sixty-four octavo pages (Spedding, Bibliography, 432). With two editions of each individual book and nine editions of the bound sets of individual books in four volumes, the periodical was uniquely published due it being issued and reprinted at different times over three decades. Although we do not usually include periodicals, Haywood’s Spectator justifies its rightful place in WPHP as both reprinted periodical and collected book form.

Opposite Steele and Addison’s fictitious Mr. Spectator—the quiet observer of London’s civil society—Haywood’s Female Spectator is presented as his more experienced and reformed sibling, moralizing readers through recounting the mistakes of her coquettish past. She bestows upon readers the wisdom she gained from her past, hoping that her experiences as an urban flirt will help readers inform their own. Just as Mr. Spectator collaborated with his club of writers, the Female Spectator references a coterie of women in her moralizing commentary: the married and witty Mira, the unnamed Widow of Quality, and the unmarried and youthful Euphrosine, all characterized by their marital status. Scholars generally agree, however, that Haywood was the only author of the periodical despite contemporary advertisements referencing ‘Authors’ (King 144; Koon 46; Spedding, Bibliography 431–32). However, in her article, “The Basis for Attribution in the Canon of Eliza Haywood,” Lear Orr argues that although it is “probable” (360) that Haywood is the author of The Female Spectator, there is no explicit evidence linking her to this periodical. In cases where authorship is questioned, the WPHP team lists the alleged author in the Contributors field, and indicates in the Notes field if attribution is uncertain.

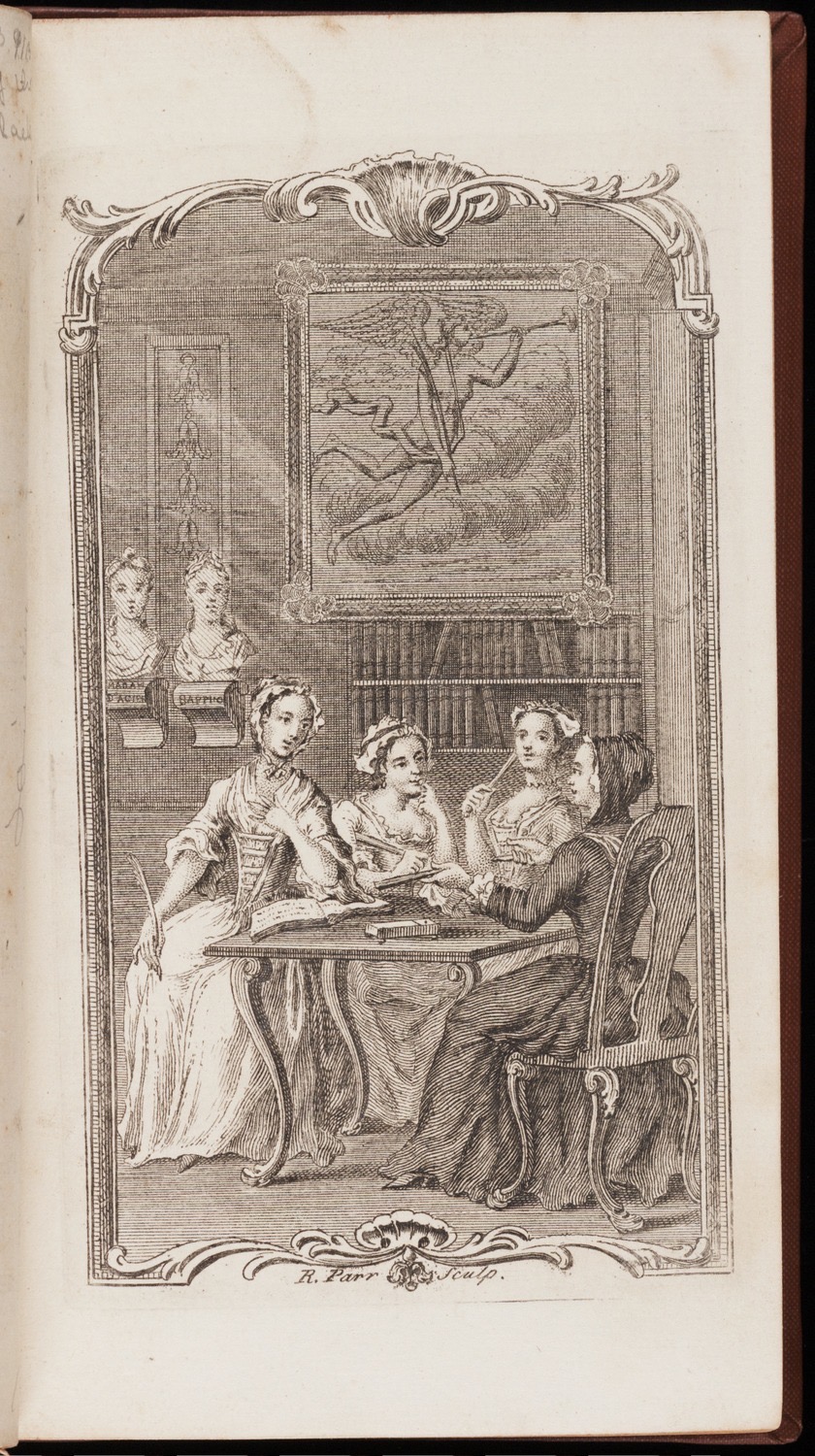

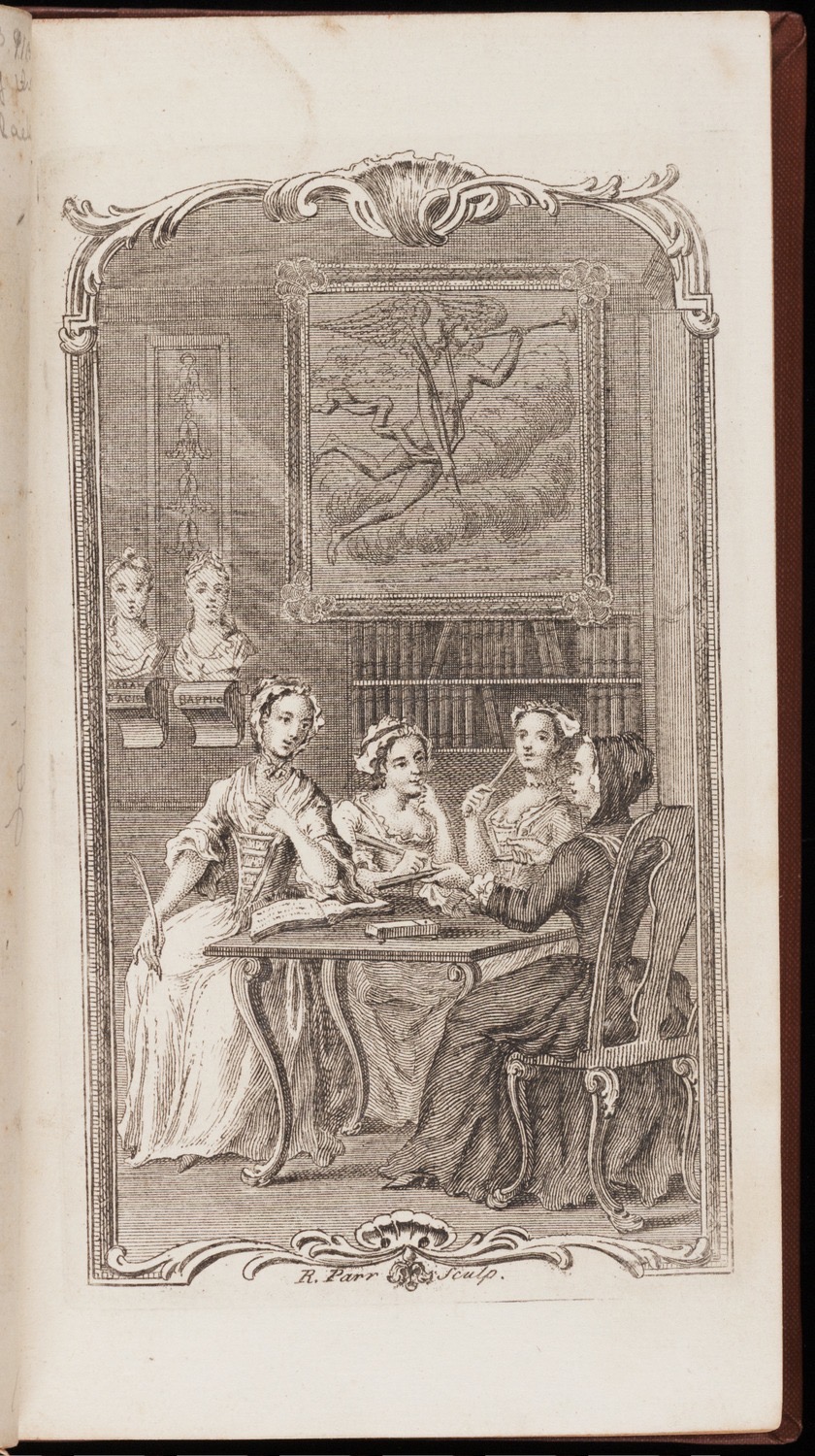

Figure 4. The frontispiece of the first edition is engraved by Remi Parr. Note the Female Spectator on the far left, holding a quill, with Euphrosine, Mira, and the Widow next to her (Barchas 63). “[Untitled plate.]” Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University, Z17 275.

A standard monthly installment of The Female Spectator comprises single-subject essays with domestic commentary on marriage, manners, and morals while advocating heavily for education and engaging with readers through letters. Haywood neglects to mention foreign affairs because, in her words, these discussions are too often “found in the public Papers” (Koon 47).

Although the periodical regularly depicts upper-class women in its pages, it is generally agreed by scholars that middle-class women were the primary reading audience, often addressed “as responsible human beings with the same ambitions, desires, and needs as their fathers, their brothers, and their husbands” (Koon 54). In 1753, Gardner advertised The Female Spectator for “younger and politer Sort of Ladies” in Volume 1 of Haywood’s History of Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy (Spedding “Measuring,” 201n38).

Figure 5. Advertisement behind the title page in the first edition of The History of Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy (1753). HathiTrust Digital Library.

The periodical, however, provoked generally unfavourable responses in its time. Notably harsh was the reaction of Laetitia Pilkington, who stated that it was a collection of “insipid”, “trite”, and “stale” stories (King 114). However, Clara Reeve, in her Progress of Romance (1785), notes that “Betsy Thoughtless is reckoned her best Novel; but those works by which she is most likely to be known for posterity, are the Female Spectator, and the Invisible Spy” (Spedding, “Measuring,” 211n57). Lady Sarah Pennington similarly praises Haywood’s Spectator as “entertaining” and “religiously constructive” decades after her death in An Unfortunate Mother’s Advice to her Absent Daughters (1789) (Spedding, “Measuring” 205).

Newly positioned in the public literary milieu as a periodical that offered a unique perspective of women, The Female Spectator was not as successful as other periodicals in the period and did not attract nearly as much interest as The Spectator. Haywood likely received an income of 60 guineas for the two years of its run, very welcome to her but still far less than her male peers. However, the periodical was a success by Haywood’s own standards, ranking “as the third most frequently reprinted work [of hers] in the eighteenth century,” with editions in French, Italian, and German by 1756 (Spedding, “Measuring” 194–95).

Figures 6 and 7. Vol. 1 title pages of the seventh (1771) and eighth (1775) London editions, a noticeably more minimalistic design than that of the first and second London editions above.

The Female Spectator was by no means the first periodical for women—John Dunton’s 1690 Athenian Mercury issued “special editions” for women in The Ladies Mercury—yet it was the first to offer insights for women by a woman. As a conduit for intellectual exchange that sought to help women navigate eighteenth-century society, the periodical’s position in literary history suggests that women were not merely treated as a secondary audience for special editions but as “a primary audience in and of themselves” (Wright and Newman 22). Also overlooked is Haywood’s capacity as journalist and essayist; recent Haywood scholarship calls attention to her as an author and bookseller with less attention to her expert balancing of primarily masculine genres and high art forms, the journal and essay, while addressing the ostensibly low art form of domestic life. Although less popular than its contemporaries, Haywood’s Spectator addressed women as having the same aspirations as men and communicated the perspectives of women as polite, educated, and honourable beings that were otherwise ignored. As one of her best known works, the periodical likely empowered its female audience in the period, and it is one that makes a significant contribution to our title data.

WPHP Records Referenced

Haywood, Eliza (person, author)

A Bibliography of Eliza Haywood (source)

Love in Excess; or, The Fatal Inquiry (title)

The Female Spectator, Vol. 1 (title, first London edition)

The Female Spectator, Vol. 1(title, second London edition)

Gardner, Thomas (firm, publisher)

Contributors (role)

History of Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy (title)

Pilkington, Laetitia (person, author)

Reeve, Clara (person, author)

The Progress of Romance (title)

The History of Betsy Thoughtless (title)

The Invisible Spy (title)

Pennington, Lady Sarah (person, author)

An Unfortunate Mother’s Advice to her Absent Daughters (title)

The Female Spectator, Vol. 1 (title, seventh London edition)

The Female Spectator, Vol. 1 (title, eighth London edition)

Works Cited

Barchas, Janine. “Apollo, Sappho, and—a Grasshopper?! A Note on the Frontispieces to The Female Spectator.” Fair Philosopher: Eliza Haywood and the Female Spectator, edited by Lynn Marie Wright and Donald J. Newman, Bucknell UP, 2006, pp. 60–71.

King, Kathryn R. A Political Bibliography of Eliza Haywood. Pickering & Chatto, 2012.

Koon, Heather. “Eliza Haywood and the ‘Female Spectator.’” Huntington Library Quarterly, vol. 42, no. 1, Winter 1978, pp. 43–55.

Orr, Leah. “The Basis for Attribution in the Canon of Eliza Haywood.” The Library, vol. 12, no. 4, December 2011, pp. 335–75.

Spedding, Patrick. A Bibliography of Eliza Haywood. Pickering & Chatto, 2004.

Spedding, Patrick. “Measuring the Success of Haywood’s Female Spectator (1744–46).” Fair Philosopher: Eliza Haywood and the Female Spectator, edited by Lynn Marie Wright and Donald J. Newman, Bucknell UP, 2006, pp. 193–211.

Wright, Lynn Marie and Donald J. Newman. “Introduction.” Fair Philosopher: Eliza Haywood and the Female Spectator, edited by Lynn Marie Wright and Donald J. Newman, Bucknell UP, 2006, pp. 1–6.