This post is part of our Black Women's and Abolitionist Print History Spotlight Series, which will run between 19 June and 31 July 2020. Spotlights in this series focus on our work to find Black women who were active participants in the book trades during our period, to acknowledge the ways in which white female abolitionists exploited print’s powerful potential for eliminating slavery, and to revisit the lives and books published by well-known Black female authors.

Authored by: Hanieh Ghaderi and Kandice Sharren

Edited by: Michelle Levy and Kate Moffatt

Submitted on: 07/31/2020

Citation: Ghaderi, Hanieh, and Kandice Sharren. "Lydia Maria Child's Radical Appeal." The Women’s Print History Project, 31 July, 2020, www.womensprinthistoryproject.com/blog/post/31.

Figure 1. Lydia Maria Child in 1870. Wikipedia.

Figure 1. Lydia Maria Child in 1870. Wikipedia.

Lydia Maria Child’s An Appeal in Favor of That Class of Americans Called Africans (Boston 1833) was "the foundational text of the American abolition movement" (Fanuzzi 78). According to Carolyn Karcher, the Appeal was the first book by a white woman written in support of the immediate emancipation of enslaved people in the United States (175). It was published at Child’s expense, as Allen & Ticknor, the book's publishers, were generally unwilling to publish books solely at their own risk (Winship 16). Published in the same year that the 1833 Emancipation Act was passed in Britain, Child's work was the product of three years of research and writing (Karcher 178) and provides one of the first full-scale analyses of race and slavery in America, developing "a coherent argument addressing all aspects of the slavery controversy – moral, legal, economic, political, and racial" (Karcher 176). In this wide-ranging analysis, Child represents slavery as a system rather than a personal history, part of a range of racist practices, which also included miscegenation laws, limited opportunities for work and schooling, and discrimination in the northern states. This approach, along with her arguments in favour of immediatism, aligned Child with William Lloyd Garrison, the editor of the anti-slavery newspaper The Liberator, which published women’s abolitionist writing, including the speeches of Maria W. Stewart (the subject of last week’s spotlight by Michelle Levy). In general, women were central to the Garrisonian movement, which "granted women, no matter how demure or subjugated they might be at home, a visible and powerful place in the political world" (Brown 67).

During her lifetime, Lydia Maria Child became famous as a writer and activist in favour of justice and equality for marginalized people, including Native Americans, Black people, and women (Karcher 41). By the time she published the Appeal, she was already a successful writer, whose published works included fiction, household management, education, and biography; she was also the editor of the Juvenile Miscellany. Her works often contained radical ideas challenging social injustice and documenting American history from a woman’s perspective (Karcher 16–19). For instance, her first book, Hobomok (1824), included a representation of interracial marriage: the heroine Mary Conant rebels against her father by marrying a Native American. This plot shocked contemporary readers, even though, as Karcher observes, the novel ultimately offers a "reassuring negation of a threat to white supremacy and patriarchal authority" (21) when the heroine rejoins her community and marries a white man. Child’s next novel, The Rebels, or Boston Before the Revolution (1825) also challenged patriarchy and power relations in society by representing historical events from a female perspective (Karcher 41). Child brought her interest in women’s lives and experience to bear on non-fiction as well, publishing practical books about household management, including the popular The Frugal Housewife, Dedicated to Those Who Are Not Ashamed of Economy (1829), which went into over thirty editions by 1855 and which was later retitled The American Frugal Housewife to avoid confusion with Susannah Carter’s earlier work, also titled The Frugal Housewife. She also wrote The Mother’s Book, an educational manual widely reprinted in America and Britain. In 1832, she published The Biographies of Madame de Staël, and Madame Roland and The Biographies of Lady Russell and Madame Guyon, research-intensive works that required her "to consult many volumes, most of which contained but little" (Biographies of Madame de Staël and Madame Roland viii).

Child brought her experience as a successful writer in these different genres to An Appeal in Favor of That Class of Americans Called Africans, which combines detailed historical research with emotional appeal and economic arguments. The first two chapters outline the history of Black slavery, comparing it to the practice of slavery within different countries and different historical periods. Child’s arguments were strongly influenced by British and French abolitionists, Thomas Clarkson and Abbé Reynal. She quotes extensively from Clarkson, whose Essay on the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species (1787) and History of the Abolition of the African Slave-Trade (1808) offer thorough historical studies of the eighteenth-century abolitionist movement in Britain. Like Reynal, Child presented a well-researched narrative that outlined the history of Europeans’ enslavement of Africans, beginning in 1442; like Clarkson, she described, often in graphic detail, the experiences of countless individuals who suffered under slavery, a strategy designed to "excite our pity on the one hand, . . . [and] provoke our indignation and abhorrence on the other" (Clarkson 18–19).

Figure 2. Title Page of Child's Appeal in Favor of that Class of Americans Called Africans (1833). Hathi Trust Digital Library

Figure 2. Title Page of Child's Appeal in Favor of that Class of Americans Called Africans (1833). Hathi Trust Digital Library

The Appeal relies on powerful imagery to present its arguments in visceral terms. Child’s extensive research allows her to include descriptive passages that depict the horrible conditions that enslaved people had to work in, as well as the difficulties that they faced on a daily basis. She writes:

Husbands are torn from their wives, children from their parents...sometimes they are brought from a remote country; obliged to wander over mountains and through deserts; chained together in herds; driven by the whip, scorched by a tropical sun, compelled to carry heavy bales of merchandize; suffering with hunger and thirst; worn down with fatigue, and often leaving their bones to whiten in the desert....in some places, travelers meet with fifty or sixty skeletons in a day. (6)

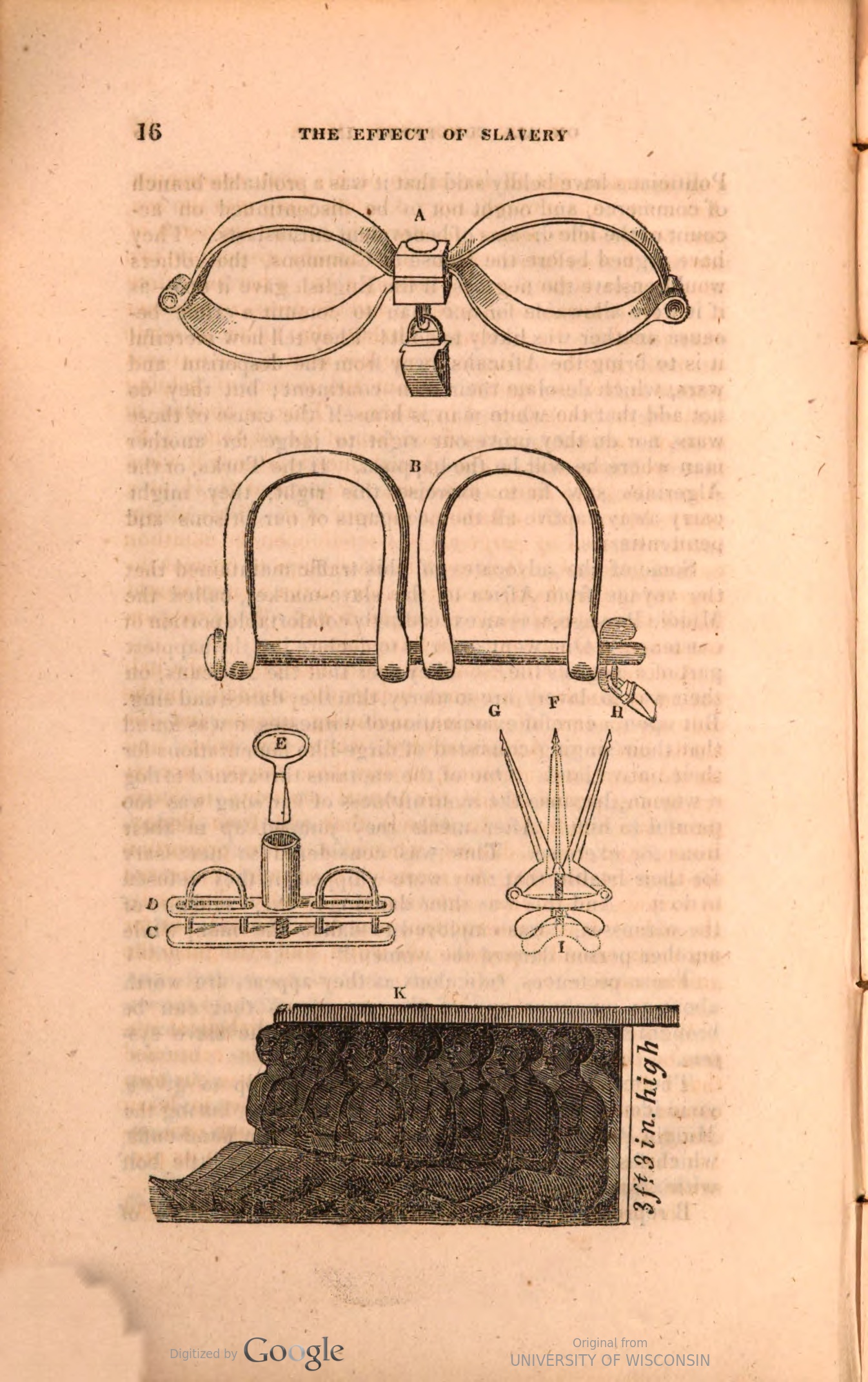

Child's use of novelistic detail to describe the horrors of slavery encourages readers to imagine the physical experiences of enslaved people. In addition to vivid description, Child illustrates her arguments with simple figurative language: "All living creatures, that can, by any process, be enabled to perceive moral and intellectual truths, are characterized by similar peculiarities of organization. They may differ from each other widely, but they still belong to the same class. An eagle and a wren are very unlike each other, but no one would hesitate to pronounce that they were both birds" (155). This comparison of different bird species to different races emphasizes similarity over difference to support her argument in favour of racial equality. Child also literally illustrates her points by using various images, as she uses an engraving of shackles and instruments of torture to drive home the cruelty of slavery.

Figure 3. Illustration from Child's Appeal. Hathi Trust Digital Library.

Figure 3. Illustration from Child's Appeal. Hathi Trust Digital Library.

In addition to documenting the suffering of enslaved people, Child speaks to enslavers in their own language, asking them to end slavery for their own economic and moral good. She contends that slaveholders can benefit from the work of free laborers, claiming that slavery is not actually an economic boon:

The slave is bought, sometimes at a very high price . . . when the slave is ill, a physician must be paid by the owner . . . the slave is to be taken care of in his old age . . . the slave does not care how slowly or carelessly he works . . . the slave is indifferent how many tools he spoils . . . The free man will be honest for reputation's sake, but reputation will make the slave non the richer, nor invest him with any of the privileges of a human being . . . (77–78)

The negative impacts of slavery on enslavers were not only economic, but also moral, with consequences for the entire country; Child warns that "we cannot inflict an injury without suffering from it ourselves" (Appeal 11). She also seems to foresee the violence of the Civil War when, after outlining the divisions that debates about slavery have created between Northern and Southern states, she asks: "Who does not see that the American people are walking over a subterranean fire, the flames of which are fed by slavery?" (128).

Although Child’s emphasis is on bringing about an end to slavery, she recognizes that it is made possible by racism more generally. In the second half of her book, she argues against the hypocrisy of groups like the American Colonization Society that claimed to be in favour of emancipation, but were unwilling to antagonize white enslavers to achieve it. For example, the fifth chapter, "Colonization Society, and Anti-Slavery Society," sets the two approaches taken by leading abolitionist societies against each other. In it, Child objects to the aims of the American Colonization Society, which stated that it aimed to end slavery by "by gradually removing all the blacks to Africa" (Appeal 123) and challenges its refusal to antagonize the Southern states. According to Child, the policies of the Colonization Society are motivated by racism: "its members write and speak, both in public and private, as if the prejudice against skins darker colored than our own, was a fixed and unalterable law of our nature, which cannot possibly be changed" (133). By contrast, Child argues, the Anti-Slavery Society’s calls for immediate emancipation seem inflammatory but "is the only way to prevent insurrections" (142)—that is, emancipation ends the danger of slave rebellions by ending slavery.

Child also rejects arguments about the intellectual and moral inferiority of Black people through examples of notable Black writers and intellectuals, including Phillis Wheatley (read Amanda Law’s spotlight on Wheatley here), and Ignatius Sancho (his wife Ann was a bookseller profiled by Kate Moffatt here). Miscegenation, which Robert Fanuzzi identifies as "the abiding interest of her abolitionist career" (80–81), is addressed in the Appeal, which includes one of the first defences of interracial marriages (Karcher 176).

Following the publication of the Appeal, Child remained active in the abolition movement, publishing pamphlets such as Authentic Anecdotes of Slavery around 1835 and the Anti-Slavery Catechism in 1836. In the 1840s, she began using fiction to forward her abolitionist views, publishing stories such as "The Quadroons" (1842) and "Slavery’s Pleasant Homes" (1843) in the abolitionist periodical Liberty Bell (Fanuzzi 77) and editing the National Anti-Slavery Standard between 1841 and 1843. She also edited the memoirs of Harriet A. Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861), which was published under the pseudonym Linda Brent. As in earlier slave narratives such as Mary Prince’s (featured in this spotlight by Sara Penn), Jacobs details the sexual violence inflicted on her by her enslaver; Child’s introduction notes, "I am well aware that many will accuse me of indecorum for presenting these pages to the public . . . but the public ought to be made acquainted with its [slavery’s] monstrous features" (Douglass and Jacobs 128).

Child’s Appeal, published in 1833, provides one of the earliest comprehensive treatments of the evils of slavery and racism in the United States. It joins with other important works published in the 1820s and 1830s that witnessed the culmination of fifty years of abolitionist activities in Britain, including Elizabeth Heyrick’s Immediate, Not Gradual Abolition (1824; read Victoria DeHart’s spotlight on Heyrick here) and Mary Prince’s History (1831) and the passing of the Slavery Abolition Act by British Parliament in 1833, as well as the birth of the radical movement on the other site of the Atlantic, as is evident in Maria W. Stewart’s publications of 1831, 1832, and 1835. As with these other writers and activists, Child focused on the particular consequences of slavery and racism for women, making her one of the earliest feminist advocates for racial justice.

WPHP Records Referenced

Child, Lydia Maria (person, author)

An Appeal in Favor of That Class of Americans Called Africans (title)

Allen & Ticknor (firm, publisher)

William Lloyd Garrison and Isaac Knapp (firm, publisher)

Stewart, Maria W. (person, author)

"Maria W. Stewart, Activist for 'African rights and liberty'"(spotlight by Michelle Levy)

Hobomok (title)

The Rebels, or Boston Before the Revolution (title)

The Frugal Housewife, Dedicated to Those Who Are Not Ashamed of Economy (title)

The American Frugal Housewife (title)

Carter, Susannah (person, author)

The Frugal House Wife (title)

The Mother’s Book (title)

The Mother’s Book (title, 1836 Scottish corrected edition)

The Biographies of Madame de Staël, and Madame Roland (title)

The Biographies of Lady Russell and Madame Guyon (title)

"The Transatlantic Publication of Phillis Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral" (title spotlight by Amanda Law)

"A Search for Firm Evidence: Uncovering Ann Sancho, Bookseller" (spotlight by Kate Moffatt)

Prince, Mary (person, author)

"The First Slave Narrative by a Woman: The History of Mary Prince, a West Indian Slave" (spotlight by Sara Penn)

Heyrick, Elizabeth (person, author)

Immediate, Not Gradual Abolition (title)

The History of Mary Prince, a West Indian Slave (title)

"Elizabeth Heyrick, Mother of Immediatism" (spotlight by Victoria DeHart)

Works Cited

Brown, Lois A. "William Lloyd Garrison and Emancipatory Feminism in Nineteenth-Century America." William Lloyd Garrison at Two Hundred, edited by James Stewart, Yale UP, 2008, pp. 41–72.

Clarkson, Thomas. The History of the Rise, Progress, and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave-Trade by the British Parliament, 2 vols. L. Taylor, 1808.

Douglass, Frederick and Harriet Jacobs. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave and Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Modern Library, 2004.

Fanuzzi, Robert. "How Mixed-Race Politics Entered the United States: Lydia Maria Child’s Appeal." ESQ: A Journal of the American Renaissance, vol. 56, no. 1, 2010, pp. 71–104.

Karcher, Carolyn L. The First Woman in the Republic A Cultural Biography of Lydia Maria Child. Duke UP, 1994.

Winship, Michael. American Literary Publishing in the Mid-Nineteenth Century: the Business of Ticknor and Fields. Cambridge UP, 2002.